- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

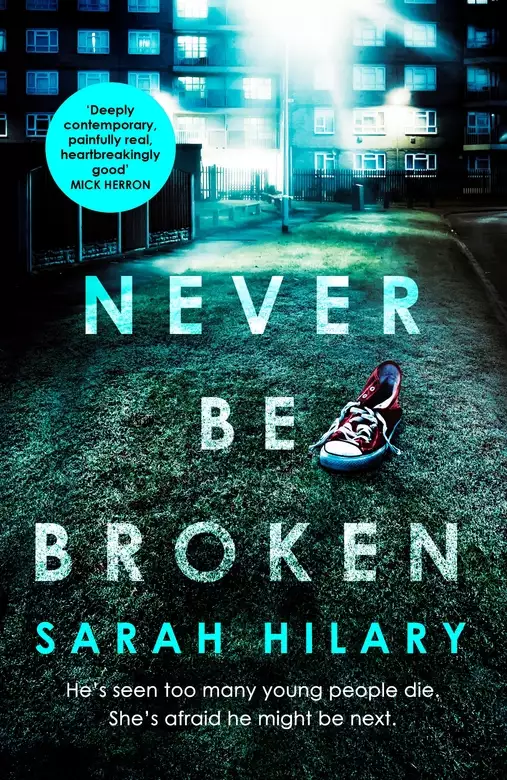

Compulsive, gripping and dark, NEVER BE BROKEN is the stunning new novel in the Marnie Rome series, for fans of Peter James, Mark Billingham, and Val McDermid.

Children are dying on London's streets. Frankie Reece, stabbed through the heart, outside a corner shop. Others recruited from care homes, picked up and exploited; passed like gifts between gangs. They are London's lost.

Then Raphaela Belsham is killed. She's thirteen years old, her father is a man of influence, from a smart part of town. And she's white. Suddenly, the establishment is taking notice.

DS Noah Jake is determined to handle Raphaela's case and Frankie's too. But he's facing his own turmoil, and it's becoming an obsession. DI Marnie Rome is worried, and she needs Noah on side. Because more children are disappearing, more are being killed by the day and the swelling tide of violence needs to be stemmed before it's too late.

NEVER BE BROKEN is a stunning, intelligent and gripping novel which explores how the act of witness alters us, and reveals what lies beneath the veneer of a glittering city.

Release date: May 16, 2019

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Never Be Broken

Sarah Hilary

The car alarm was still shrieking when Marnie reached the crime scene.

‘Can’t we shut that off?’ She’d heard it from two streets away, a giddy note of outrage under London’s morning soundtrack, making her want to turn her own car around and head the other way. But here she was, doing her job, with a police crime-scene officer so young she looked around for a grown-up. ‘Surely we can shut it off?’

It was hard enough being this close to the wreckage – twisted metal, bloodied broken glass – without the sickening wail from inside the vehicle.

‘The sensor’s bust.’ The young PCSO wiped at his mouth. ‘Believe me, we’ve tried.’

Marnie turned away to rest her eyes, waiting for the pain in her chest to ease, or at least to blunt a little. She was finding it hard to breathe. Her throat was pinched tight with panic, and with guilt. Guilt rode with her most days, but panic was a new companion. She was unused to its temperament, the hiccupy whispering in her ear: Are we there yet? Are we done?

Behind her, cars crawled two lanes deep, the morning’s rush hour reduced to horns and hand signals. White noise reached from the ring road, whiplashing when it hit the tailback. The dregs of the sound slipped around the sides of Erskine Tower to find her.

She didn’t look at the tower; she didn’t need to. It was there at the periphery of her vision, would be there if she walked a quarter of a mile in any direction. Three hundred and thirty feet of municipal sixties high-rise, a crude concrete finger flipping off the rest of west London. From street level, the block was gaunt, its shadow a chilly welt running up the road from the low-lying bohemia of Notting Hill before striking out for Ealing, queen of London’s suburbs. You wouldn’t want to be here after dark, but at 8 a.m., the neighbourhood was hung-over, abandoned. Flanked by that rarest of London landmarks: unmetered parking spaces, a greater abomination in the eyes of city planners than the ugly high-rise itself.

This morning, empty flags of sky hung either side of Erskine Tower. Smoke was seeping from a window at the very top, so far away it looked like a cloud unravelling. If she stood very still and held her breath in her chest, it was a day like any other.

Rain spotted her face. One of those arbitrary handfuls that falls on a dry day, smelling of rust and copper. Unless it was the smell of blood from the ruined bonnet of the car. Her skin recoiled. She took a step back, away.

The PCSO warned, ‘Mind your feet, ma’am.’

She looked down to see Noah Jake’s shirt twisted in the gutter.

Are we there yet? Are we done?

Noah’s shirt. She recognised the blue cotton, its smooth weave stained by the same blood that was running from the bonnet to pool under the car’s front tyre. The shrill of the alarm drowned out the smaller sounds of brittle chips of glass falling from the wreckage. An Audi, Noah had taken it from the police station less than an hour ago. She hadn’t looked up when he’d said he was heading out; only nodded with her eyes on the morning’s paperwork. She hadn’t said, ‘Good luck,’ or, ‘Take care,’ or anything at all. He’d gone without a glance from her, or a word.

‘What a mess.’ The PCSO sucked air between his teeth.

Marnie lifted a hand to brush the rain from her face, holding it there for a long moment to block out the drunken lurch of the tower. Seeing through the bars of her fingers all the ways in which the morning’s chaos had altered everything.

Forty-eight hours earlier

‘Is Detective Sergeant Jake around?’

‘Who’s asking?’ DS Ron Carling spun in his chair, bending his brow at the newcomer. He’d become protective of Noah in the last ten weeks, a contingency neither man could’ve foreseen when they first began working together two years ago.

Watching from the window of her office, Marnie saw the visitor smile.

‘Karie Matthews.’ The woman held out a hand. ‘Dr Matthews.’

Ron rose to shake her hand, losing a little of his gatekeeper gruffness. Karie Matthews was small even in her heels, wearing a dark grey dress under a bright grey jacket tailored to her slight frame. Her fair hair was cropped short, shot through with silver. Her eyes, deep-set and expressive as a dancer’s, fixed on Ron’s face, giving him her full attention. Marnie saw him soften, fighting his first instinct to protect Noah, because that was what you did when your mate was being subjected to occupational health and welfare counselling. No one on the team would deny that Noah needed support, as anyone in his circumstances would, but few believed it was best provided by a stranger, someone from outside the team.

‘He’ll be in a bit later,’ Ron was saying. ‘Detective Inspector Rome’s around, if you need her?’

Karie Matthews said, ‘It’s always a pleasure to talk with DI Rome.’

Marnie couldn’t fault the woman’s manner or her charm, but she opened the door to her office reluctantly, as if inviting a viper inside. It wasn’t Karie’s fault, she knew. It was the memory of her own time with Occupational Health and Welfare, seven years ago. She’d resisted the referral by her line manager, OCU Commander Tim Welland, just as Noah was resisting Marnie’s referral now. She had to hope that Karie, like Lexie seven years ago, would keep faith with the task until Noah was able to benefit from it.

Noah Jake was speaking with his brother, Sol. More precisely, he was arguing with Sol. As kids, he’d rarely lost an argument to his little brother. But that had been down to Sol’s habit of losing interest and walking away, rather than Noah’s persuasive skills. It was different now. Now Sol was the one seeking him out to argue, about everything. Noah’s clothes, his breakfast choices, how he spent his evenings. He wouldn’t have minded, but it was ten weeks since Sol had died. Noah was arguing with a ghost.

‘Seriously, bruv. That tie with that suit?’

‘What’s wrong with this tie?’ Noah asked the question in spite of the promise he’d made to himself last night that he would stop rising to Sol’s bait. ‘Exactly?’

‘Just you look like an undertaker.’

Noah met his dead brother’s eyes in the mirror. ‘You’re obsessed with funerals.’

‘Yeah?’ Sol picked at his teeth with his thumbnail, a habit he’d had as a kid. ‘You’re the one dressing like an undertaker.’ He slouched into the wall, his pink hoody a blast of carnival music in the bedroom Noah shared with Dan, who was taking a shower and couldn’t hear the argument over Noah’s sartorial choices.

He set the tie aside. ‘So I’m hoping to see Mum at the weekend.’

Sol stiffened, then shook his head. ‘Not cool. I’m not up for that.’

‘She’s on her own, and the last time she was on her own—’

‘Not like that.’ Sol cut him short. ‘It’s not like that.’

‘Well, what is it like?’ Noah hadn’t seen his mum in days.

‘She’s got new friends.’ Sol pulled a face. ‘Talks with them all the time, just like Dad said. And you know what? It’s your fault.’ He pointed both fingers at Noah, accusingly. ‘Your. Fault.’

‘How is it my fault?’

‘You had to buy her that computer. Showing off, flashing your cash. I mean, what were you t’inking?’ Jabbing his fingers at his temples. ‘What was going through your head?’

As someone who’d been conversing with a ghost for the last ten weeks, Noah wasn’t sure he could give a convincing answer to questions concerning the contents of his head.

‘Dad said she doesn’t get out much at the moment.’ He reached for a different tie. ‘The computer’s so she can keep in touch, do her shopping online, that sort of thing.’

‘Oh, she does her shopping online.’ Sol burst out laughing. ‘That and everything else.’

Noah’s fingers chilled. ‘Her new friends . . . they’re online friends?’

‘Online freaks is what they are.’ Anger altered Sol’s voice. ‘Online mind-screwing freaks.’

‘And Mum chats with them?’

‘All the time. Dad said, remember?’ Sol collapsed onto the bed, hiding his face in the crook of his elbow. ‘So, yeah. If you want to go round, you’re on your own. Not cool, not coming.’

Noah looked down at his brother, processing what Sol had said. Or rather what his subconscious was trying to tell him through the medium of Sol’s ghost. Imagining their mum, Rosa, with an internet addiction on top of everything else. ‘Is she taking anything right now?’

Pills, he meant. Sometimes the pills helped. But often they made it worse.

‘Yeah.’ Sol’s voice was muffled by his arm. ‘Some herbal shit one of her new mates came up with. Dad says it’s just vitamins, can’t do her any harm. Well, you heard him saying it. Except I’ve not seen her this weird in years. She’s never been right, but this’s wrong. Spending all her shit on water and batteries, and Dad pretending that’s okay, that’s normal? Bullshit.’

‘Water and batteries?’ Noah echoed.

Dad had told him about this, he must’ve done. How else would his subconscious know the words to put into Sol’s mouth? But Noah couldn’t remember the conversation. It made him wonder what else he’d forgotten from the ten weeks since he’d lost his brother.

‘And tinned crap,’ Sol was saying. ‘House’s a disaster zone, you should see it. Your room? Wall-to-wall water, for when it stops coming out of taps. Whole world’s going to shit, that’s her thing now.’ He laughed, unhappily. ‘She’s given up the brushes. No more cleaning, no more nothing. Boom. Apocalypse, that’s her new thing.’

‘She’s stockpiling food and water.’ Noah’s eyes throbbed. ‘Is that what you’re saying? Dad said . . . And her new friends, they’re encouraging this?’

‘They’re all doing it, bruv. Latest craze. Latest boom.’ Sol kicked a foot at the bed. ‘Fucking preppers, innit?’

Noah and Marnie had dealt with a case involving preppers, two years ago. He’d witnessed their paranoia and fear first-hand. He’d never imagined his mum would fall prey to it, despite knowing how fragile she was. And it was all so much worse since—

‘Noah?’ Dan was towelling his hair, barefoot in jeans and a T-shirt. ‘Were you on the phone?’

Noah shook his head. ‘Just . . .’

‘Thought I heard voices.’ Dan scrubbed at his head with the towel.

Noah glanced at the empty bed, its covers pulled smooth. No Sol, not even the shape of him there. Because his brother was dead. Sol was dead. There was only the neat space where Noah lay all night blinking at the ceiling, waiting for the morning so he could dress and leave the house. Bury himself in work, so deep he couldn’t hear Sol speaking to him, picking a fight over the route he’d taken to the police station, or the theory he had about the case they were working. Sol would’ve argued with DI Rome had Noah let him. He didn’t, holding his brother at arm’s length for moments like this one, when Dan returned from the shower with his hair wet, eyes dark with worry for Noah and the way he was dealing with his grief – or not dealing with it.

‘This tie.’ Noah held up the one Sol had criticised. ‘It goes with the suit, right?’

Dan slung the wet towel around his neck and crossed the room, taking the tie from Noah’s hand and running it under the collar of his shirt before knotting it. They were so close, Noah could see the razor burn on Dan’s jaw. He leaned in to test its smoothness with his lips, tasting shaving foam, catching the warmth of Dan’s skin, wishing he could steal a little for himself. He was numb with cold, pricked by goose bumps from his brother’s ghost.

‘Don’t go to work today.’ Dan curled his palm around the back of Noah’s neck, pulling him close. ‘Stay home. Let me—’

‘Don’t tempt me.’ Noah straightened, smiling.

‘Why not?’ Dan’s elbow was hard and spare in his hand. ‘You said yourself DI Rome wanted you to rest.’

‘So we’d be resting?’

But Dan shook his head at Noah’s smile. ‘Afterwards, sure. It’s what you need.’

‘I need to work.’ His brother’s pink hoody was in the doorway, heading down the stairs to the street. He couldn’t let Sol out there on his own, it wasn’t safe. ‘See you tonight. I’ll cook, okay?’

‘How is he?’ Karie Matthews folded her hands in her lap, considering Marnie’s question. ‘Relying on work to see him through this. Resenting time away from work, resisting the counselling. So far so typical.’ Her smile wore a frown. ‘How is he here?’

‘The same. Conscientious, clever, compassionate. The best detective I’ve worked with.’ Marnie met the woman’s gaze. ‘Is he working too hard? Yes, but he always has. Do I have serious concerns about his welfare? No, but neither am I complacent. We’re meeting regularly, and he’s talking with me. Not as much as I’d like, or you would like, but enough for me to believe it’s progress.’

‘These cases you’re working on. Are they affecting him, do you think?’ Karie had averted her gaze from the evidence boards in the incident room. All those young faces, eyes burning black and white. It was hard to look at them. Harder still when a new face was added, which was happening all too often as the investigations dug deeper.

‘Of course. But no more than they would’ve done two months ago. It’s affecting us all.’

‘He’s worked on tougher cases,’ Karie agreed. ‘Dead brothers. Vigilantism. The personal attack two years ago that left him with broken ribs.’

Marnie waited for a question.

‘He’s been through a great deal. I’m not trying to make a special case for him . . .’ Karie cut herself short, shaking her head. ‘Or perhaps I am. I like him a little too much, that’s the truth of it. I admire his courage, and his commitment. And I worry for him. Professional distance only gets us so far in this line of work.’

‘I understand. I feel the same. He’s an exceptional detective, but more than that, he’s a good man. Perhaps if it wasn’t so rare . . .’

They shared a sad smile.

‘He needs to work,’ Marnie said. ‘It would feel too much like punishment for him to be signed off. Of course I’d do that if it became necessary. Nothing’s worth risking his recovery. If it comes to that, he wouldn’t want to jeopardise the integrity of the investigation. He might resist it, and resent it, but he’d understand. He wants these prosecutions as badly as the rest of us, maybe more.’

She’d seen Noah studying the evidence boards, meeting those stares head-on, refusing to look away. Frank Reece and the others. He had committed their names to memory, and their faces. They were haunting his dreams, driving his days. Children, many recruited from care homes, picked up and held in debt bondage. Exploited, or simply killed. Used to run guns or drugs across county lines, passed like gifts between gangs. London’s lost.

‘Modern-day slavery,’ Karie said softly. ‘That’s what they’re saying. I listened to a radio programme; the extent of it sounds horrific. Frightening.’

It was how most people first learned of the plight of these children – from the comfort of their kitchens or cars, in a sanitised radio broadcast. Not by looking into the faces of the exploited kids, or listening to their interviews. Those torturous hours of silence and denials, misery and anger.

‘And gangs,’ Karie was saying. ‘When that’s how Sol died.’

How Sol had lived, too. Marnie didn’t need to remind Dr Matthews of that fact.

‘Given the circumstances of Sol’s arrest, and his death . . .’ Karie shook her head. ‘And now Noah’s working on cases directly linked to gangs and knife crime.’

Sol had died in a prison yard, bleeding from a stomach wound.

‘If we could pick our cases . . .’ Marnie said. ‘But we can’t. And if we kept Noah away from crimes involving gangs or knives, he wouldn’t be working more than a case or two a year. This is London.’ She paused. ‘But I’m staying close to him. We’re talking, and I’m being careful, watching for signs of post-traumatic stress. It’s in no one’s interests to break him.’

Sol was waiting in the street with a look of disgust for Noah’s tie. He twitched the pink hood of his jacket over his head, falling into step with his brother. ‘I knew that kid, Frank Reece. Frankie.’ He sniffed, wiping his nose with the back of his hand. ‘He was a nice kid.’

Noah didn’t speak, seeing Frank’s face grinning at him from the evidence board at the station. Fifteen years old, so good-looking it hurt. Shiny brown eyes, shiny white teeth. Happy.

‘That’s no way to die.’ Sol turned his face away, reaching to pull a leaf from the hedge they were passing. ‘No way.’

Frank had died in broad daylight outside a corner shop in Tottenham where he’d stopped to buy a Capri Sun. He’d pushed the plastic straw into the drink and sucked a mouthful before he was approached by a boy of seventeen, who stabbed him twice in the heart.

Sol turned the leaf in his fingers before letting it go. ‘Better than the stomach, though.’

Noah shut his eyes, instructing his subconscious to dial down the morbidity. It wasn’t even 10 a.m. and he had a day’s work to get through, not forgetting a session with Dr Matthews.

‘Love you, bruv.’ Sol sloped sideways, peeling away, raising a hand behind his hooded head.

It worked like that sometimes: an instruction to his subconscious and Sol was gone. But it didn’t always work. Less and less, in fact, as the weeks went by. Noah had thought the opposite would be true, that his brother’s ghost would fade as the days passed, each day taking him a step further from the last time he saw Sol, the last time they spoke.

A taxi slid up to the kerb, disgorging a man in a Burberry trench coat who gave a hostile stare as he shouldered past. Noah checked his watch before patting his pockets for his Oyster card. He’d told no one, not even Dan, but he’d grown claustrophobic in the weeks since Sol died. Hated being below ground, even in a car park or underpass. Taking the Tube was his way of dealing with the pressure that crowded his chest, stuffing his head with black puffs of panic.

Thanks to Dr Matthews, he was well versed in grounding techniques, which he practised in rotation each morning while travelling to work, avoiding rush hour by forty minutes (his concession to the fear) after telling Marnie he was finding it hard to navigate the crowds. He couldn’t lie to her, and he didn’t want to. She wouldn’t in any case have believed him, knowing how deep the damage went. His kid brother killed in a prison yard, after being put away on a drugs charge. Noah’s arrest. Noah’s choice. Guilt had dug a pit at his feet into which every day he was tempted to fall. But there was too much work to be done. Other young men, lost as Sol had been. Running with gangs, in bondage to men like Shafi Ellis, who’d pulled the makeshift knife in the prison yard. Sol didn’t die like Frank Reece, whose heart was stopped by a single blow. His death was messy and slow, bleeding from a wound that shouldn’t have killed him had the response been quicker, had the men in the yard not walked on by, mouths shut, eyes averted.

The tiled wall of the Tube station slanted the sun into Noah’s eyes. He looked around for Sol, catching a flash of pink, but it was a kid’s rucksack not his brother’s hoody. The back of his neck tightened, his skin nagging. If he was going down, he’d have liked Sol with him.

The bump of bodies, shrill smell of the rails, sticky black rubber of the escalator rail. He watched the posters as they went past, screens lit and flickering. Acoustics shut his inner ear as he stepped off the escalator, stopped short by a man whose wheeled suitcase refused to roll the right way. Burned-wood aftershave, irritation bristling up the line of people pushing forward to find a way around the blockage. White mouth of the tunnel, black rails running away, black smell to match.

You can do this.

That flash of pink again – the kid’s rucksack – his subconscious fully occupied with surviving the next thirteen minutes; no room for Sol. People pushing for the carriage doors, move down inside the car, full gamut of armpits and coffee breath. He found a space and held it, slipping his wrist through the strap above his head, meeting a woman’s eye by accident and smiling as he looked away, trying to be non-threatening, but a black man was always threatening, or a man of any description if he met your eye at the wrong moment. Damn. He was becoming paranoid, on top of everything else.

His phone pulsed in his pocket. The first of the day’s messages from Dan, making him smile. He propped his head against his raised arm, relaxing into the sway and pitch of the train. He could do this. He’d ridden the Tube since he was a kid, knew all its moves. You just had to find its rhythm, like dancing. He’d go out with Dan tonight. The two of them and a hundred others in a club, music and lights, no room to think. But first, the day’s work.

Frank and Sabri, Clarke and Naomi, and the others. The boys and girls on the evidence board who’d once ridden the Tube to school or with friends, who’d known its moves and caught its rhythm as Noah was doing now. Suliat and Ashley. Kids who’d been afraid to smile at strangers or just because the roof was so low and all the tunnels too narrow, swallowing up the light like a snake.

‘Dr Matthews was here,’ Ron Carling said. ‘You just missed her.’

‘Oops,’ Noah offered. He slipped into the seat opposite. ‘Any news from Frank’s family?’

‘They’re releasing his name to the press today. And there’s a new kid.’ Ron nodded across the room. ‘Last ten minutes.’

Noah stopped what he was doing and stood, crossing to the board where the faces were waiting. Ashley with his head cocked, a careful crop of stubble on his chin. Suliat with her big smile, eyes half shut, a yellow wall of flowers behind her. Frank’s white teeth. Clarke’s blue baseball hat. The new face was white, a girl turning to greet the camera, green parka hiding her neck.

‘Raphaela Belsham.’ Ron came to stand at Noah’s shoulder. ‘Thirteen years old.’

‘Stabbed?’

‘Shot. Drive-by. Muswell Hill.’

Noah leaned in, meeting Raphaela’s eyes. ‘Her family are well-off?’

‘Yes. But I’d love to know how you got that from this.’

‘She’s wearing a Moncler.’ Noah pointed to the distinctive diamond pattern on the collar of the girl’s parka. ‘They retail for over a grand. And Muswell Hill? Not your typical spot for drive-bys.’

‘Nowhere’s off limits.’ Ron scratched the back of his head. ‘Isn’t that the new guideline? Gangs getting everywhere. Forget the postcode lottery, it’s all county lines and two fingers to the CCTV.’

‘Raphaela’s on CCTV?’

‘Yep. A dozen witnesses, too. We’ll be cross-eyed by the end of it.’

Noah put a hand on the board, just below the girl’s face. ‘Is DI Rome at the scene?’

Ron shook his head. ‘Ferguson wants anyone above DS staying wide. Too much fodder for the press pack, she says. They’ll be jumping up and down over this latest one.’

‘Then it’s you and me.’

‘Debbie and Oz.’ Ron sounded glum. ‘We’re on phones and paperwork.’

‘Detective Chief Superintendent Ferguson doesn’t want a black face on the ground?’ Noah straightened. ‘I thought that was meant to play well for the cameras.’

‘The cameras love you. Everyone loves you. But all it needs is one journo who’s done his or her homework . . .’ Ron shrugged an apology.

One journalist linking Noah Jake to Solomon Jake, whose face belonged on this or any other wall recording victims of violent crime in the capital.

‘DCS Ferguson can’t keep me locked up in here forever,’ Noah said. ‘Unless she wants an outrageous overtime invoice from Dr Matthews.’ He turned it into a joke because Ron was looking angry. ‘Hey, it’s okay. I don’t need a bodyguard, though. She should let you out, at least.’

‘And leave you with Oz the plod?’ Ron put a big hand on Noah’s shoulder and squeezed it. ‘I wouldn’t do that, mate.’

Noah returned to his desk. Funny, the things that made him want to weep. He’d yet to shed a tear over Sol, but Ron’s clumsy kindness had the bridge of his nose burning. He opened his emails, working in silence for a while. Then he got up and walked back to the boards, taking out his phone so he could capture this latest face: Raphaela Belsham in her expensive parka, wild hair tied in a topknot. He caught Ron’s eyes on him and gestured towards the door. Ron answered with a nod. Comfort break; that was normal, that was allowed.

The station corridor was furred with sound. Raised voices from the front desk, the hiss of fluorescent lighting, phones ringing around the clock. Familiar, safe. In the lavatory, Noah washed his hands and then his face, after first flipping his tie over his shoulder.

‘Still doesn’t go with the suit.’ Sol leaned against the nearest stall, pink hood down, eyes bright.

‘I’m working,’ Noah said over the running of the taps. ‘Can we do this later?’

‘Whatever, bruv. But don’t go weeping over that old pagan.’

‘Pagan?’ Noah shook water from his hands, reaching for a sheet of paper to dry his face. ‘We’re speaking patois now?’

‘Two-faced, s’all I’m saying. Hated you when you started here.’

‘Ron? He didn’t hate me. He just didn’t know me.’

‘Riiight.’ Sol drew the word out. ‘Because up close you’re irresistible.’

‘I do all right.’ Noah threw the screwed-up ball of paper at the bin. ‘Obviously I’ll do better once I get my shit together and stop talking to you.’

‘Don’t do that. Least not while you’re working this case. I can help. Know the gang Frankie Reece was running with, maybe even the lot who gunned down your new girl.’

Noah stopped what he was doing. He gripped the lip of the sink and leaned into the mirror to meet his brother’s eyes. ‘Tell me how that helps me. Just tell me what good it does? Even if you knew them, even if you ran with them. What good is that to me?’

Sol fell silent for a beat before he said, ‘You found yourself a gang. Same as me.’

‘That was years ago.’ Noah took a step back. ‘We were little kids. And I got out.’

‘Not talking about when we were kids. Talking now. You got your bass lady and that old pagan pretending to be your friend, streets you’re stamping – what endz you got? All of Greater London. Hustling the brothers, coming at us all hours, coming at our fam. Protect and serve but you’re all up in our faces, trying to boss our postcode. Metropolitan Po-leece. That’s your gang.’

It was a great speech. Noah wondered how long his subconscious had been bottling it up. And what else it had in store for him. Since Sol’s death, all bets were off. He couldn’t count on a good night’s sleep, couldn’t even use the urinal without a running commentary from his brother’s ghost.

‘The difference being we’re trying to stop the violence. The knives, the guns.’

‘Keep telling yourself that, bruv.’ Sol stepped backwards into the stall, kicking the door shut, raising his voice on the repetition: ‘Keep tellin’ . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...