Chapter 1

I learned about the death of my uncle Jake in a deeply unexpected way, which was from the CNBC Squawk Box morning show.

I had Squawk Box on from force of habit; when I was a business reporter for the Chicago Tribune I would turn it on in the mornings, in rotation with Bloomberg and Fox Business, while I and my wife Jeanine got ourselves ready for our respective days.

These days I had less need of it—substitute teachers do not usually need to be kept up on the state of the Asian markets in order to babysit a bunch of students in a seventh-grade English class— but old habits, it turns out, actually do die hard.

Thus it was, as I was preparing my peanut butter on toast, I heard the name “Jake Baldwin” from the iPad I had running on the kitchen island. I stopped mid-peanut-butter spread, knife in hand, as cohost Andrew Ross Sorkin announced that my uncle Jake, reclusive billionaire owner of the third-largest chain of parking structures in North America, had died of pancreatic cancer at the age of sixty-seven.

“Are you hearing this?” I said to my breakfast partner, who was not my wife Jeanine, because she was no longer my wife and no longer living with me. She was now back in her hometown of Boston, dating an investment banker and, if her Instagram account was to be believed, spending most of her time being well-lit in enviable vacation spots around the globe. My breakfast partner was Hera, an orange-and-white cat who, after I had retreated to my childhood home after the divorce and layoff, had emerged from the backyard bushes and informed me through meowing that she lived with me now. Hera’s breakfast was Meow Mix; she was eating on the center island and was watching Squawk Box with me, presumably to decide if Andrew Ross Sorkin was a prey animal she could smack around.

I had not known my uncle Jake was sick with anything, much less pancreatic cancer, which was the disease that had also felled fellow billionaire Steve Jobs. (My brain, on journalistic autopilot, had started writing the lede graf for my uncle’s obituary; have I mentioned that old habits die hard?) To be fair, it wasn’t that Uncle Jake had been hiding it from me. It was that he hadn’t been in contact with me, at all, since I was five years old. Jake and my dad had a falling-out at my mom’s funeral. I vaguely remember the yelling, and then after that it was like Jake simply didn’t exist. Dad preferred it that way, and Jake must have too. Jake didn’t come to Dad’s funeral, in any event.

As for me, I didn’t think about Jake at all until I was in college and started writing business-related articles for the Daily Northwestern, and discovered that half the parking structures in Evanston were owned by BLP, a private company majority-owned and entirely controlled by Jake. I tried to score an interview, figuring I might have an in, but BLP didn’t have a PR department or even contact information on its website. When I got married, I dragged an address for Jake out of my dad and sent my uncle an invite, mostly to see what would happen. Jake didn’t show, but sent a gift: berry spoons, and a cryptic note. I stopped thinking about him after that. Jake had almost no media presence and never showed up in the news, so this was easy enough to do.

Jake’s lack of paper trail was giving CNBC fits, however. I watched as Sorkin and presumably his writers struggled to say anything about a man who was obviously important—billionaires are important to CNBC, at least—but had also made his billions in the least sexy way possible. Steve Jobs had given the world the Macintosh and the iPhone and lifestyle tech like the tablet I was watching Squawk Box on. Uncle Jake had given people a place to park a car. CNBC solved this lack-of-drama problem by bringing on a reporter from Parking Magazine, the trade rag of the National Parking Association—and yes, both of those things are real.

“Oh, boo!” I said, when the reporter came on, and threw a corner of my peanut butter toast at the iPad. It bounced off the screen, leaving a peanutty smear, and landed in front of Hera, who looked up at me, confused. “It’s friggin’ Peter Reese,” I explained, waving at Peter’s obviously-being-recorded-on-a-laptop face as he explained what impact Jake’s death would have on the mission-critical world of parking garages. “He’s a terrible reporter. I should know. I worked with him.”

Hera, not impressed, ate the crumb of peanut butter toast.

I had indeed worked with Reese, at the Tribune. And he was indeed a terrible reporter; I remember one of the assistant editors in the business section miming strangling him after he had bungled an important story that other reporters, including me, then had to rescue. He and I had been laid off from the Trib around the same time. I was annoyed with him now because, while his new perch at Parking Magazine was a reputational step down from the Tribune, he was still somehow in journalism, while I was substitute teaching in my old school district. There were reasons for that—the divorce, being broke, dad getting ill and me coming back to care for him while licking my own existential wounds—but it didn’t make it any less annoying. Here was Peter friggin’ Reese on Squawk Box, living in Washington DC, while I ate my toast in a house I grew up in but didn’t technically own, with a cat as my only friend.

“Enough of that,” I said, cutting off Reese as he explained that as BLP was a private company, the demise of its owner should not have a significant effect on stock prices of other publicly traded parking companies. Which probably wasn’t true, but which no one, including Reese and Sorkin, actually cared enough about to dig into, and they were about to throw to commercial anyway.

This was the public legacy of a billionaire and his life’s work: two minutes of forgettable business reporting, and then a commercial for gastric-distress medication.

My phone took this moment to ring, an unusual occurrence in this age of texting. I looked down to see who it was: Andrew Baxter, my dad’s old friend, lawyer, and executor of his estate, which was almost entirely the house I was living in. I groaned. Whatever Andy wanted from me, it was too early in the morning for it. I let the phone go to voice mail and finished my toast.

“How do I look?” I asked Hera. I was not dressed in my usual substitute teacher uniform of dress shirt, sweater vest and Dockers; I was instead in my best suit, which was also my only suit, the one I’d worn to both my wedding and to my father’s funeral, and at no time in between those two events. It was actually only most of a suit, because apparently in the move back to my dad’s house I’d lost the shoes. I was wearing the black Skechers I had worn to dad’s funeral. No one noticed them then, and I was hoping no one would notice them today. “Would you give me a truckload of money if you saw me dressed like this?”

Hera gave a small chirrup and a slow blink, indicating her approval. Well, of course she approved. She had picked out my tie, my green one, mostly by lying on the red one after I had put it on the bed with the green one to choose between them.

“Thank you,” I said, to my cat. “As always, your approval is the most important thing.” Hera, satisfied, went back to her Meow Mix.

I looked at my watch; my appointment was twenty minutes in the future. In twenty minutes I would know the shape of my life for the next several years. Unlike my uncle Jake, it would not take billions of dollars for me to accomplish any of my life goals.

Just a few million would do.

━━ ˖°˖ ☾☆☽ ˖°˖ ━━━━━━━

Belinda Darroll looked at her computer. “So, Mr. Fitzer, you want a business loan for . . . three point four million dollars.”

“That’s right,” I said. I was sitting in Darroll’s office in the Barrington First National Savings and Loan building, which had been recently refurbished after its purchase by CerTrust, a Chicago-based financial company whose thing was buying local banks and then keeping the former branding so everyone in town would think they were still dealing with a local business and not some faceless financial behemoth. The building smelled of fresh paint and outgassing esters from the newly laid high-traffic carpet.

I had been slightly early to the appointment; Darroll had introduced herself when she came in. She said I looked familiar, and we determined she had been a freshman at Barrington High when I had been a senior. She remembered me getting in trouble as the editor of the school paper for running a story about Mr. Kincaid, a ninth-grade algebra teacher, being the biggest supplier of meth on campus. I got suspended for not showing the story to the newspaper faculty advisors before running it; Mr. Kincaid got six years at Big Muddy River Correctional Center for possession and distribution. I got the better end of that deal, I think.

Darroll asked me if I was still writing. I told her I was working on a novel. It’s the standard lie.

“You want the loan for a business you’ll have here in Barrington,” Darroll continued.

“Yes. I want to buy McDougal’s Pub.”

“Oh!” Darroll looked away from her computer to me. “I love McDougal’s.”

I nodded at this. “Everybody does.” McDougal’s had been a Barrington constant for decades, located in an enviable downtown corner while other restaurants and bars had come and gone around it. Turns out, ale and heaping plates of fries never go out of style in the Chicago suburbs.

“I had my first drink there,” Darroll said. “Well, first legal drink,” she amended.

I nodded again. “Everybody does,” I repeated.

“Do you know why they’re selling?”

“The economic downturn hurt business, plus Brennan McDougal wants to retire and none of his kids want to take over the business,” I said. “This is what happens when your kids all get college educations. they don’t want to run a bar.”

“Don’t you have a college education?” Darroll asked.

“I do, but unlike McDougal’s kids, who got MDs and MBAs, I got a journalism degree,” I said.

Darroll nodded. “That’ll do it.” She glanced at her information on the screen. “So you would take over the pub . . .”

“The pub, the restaurant next door, and the building both are in. Brennan McDougal is selling the whole thing. Everything’s already up and running. All I would need to do is walk in.”

“Do you have experience running a pub? Or a restaurant?”

“No,” I admitted. “But McDougal’s already has staff and managers.”

Darroll frowned at this. “This sector is always a risk. Restaurants fail all the time. Even with experienced managers and staff. And now is an even more precarious time for these businesses.”

“Sure,” I acknowledged. “But you said it yourself: Your first legal drink was at McDougal’s. It’s a Barrington institution. People here want it to be here. I want it to be here for them. I’m not saying there isn’t risk. When I was a reporter for the Trib I did the local business beat for a couple of years. I know how it goes for restaurants. But McDougal’s is as close as it gets to a sure thing. Heck, I’m not even going to change the name.”

Darroll clacked at her keyboard and then was silent for a moment, reading what was on her monitor. “The Zillow listing has the building for sale for three point four million,” she said. “You’re asking for the whole amount of the business.”

“I am.”

“You’re not putting down a percentage from your own assets?”

“I would like to have a margin,” I said, “for unexpected contingencies. There’s always something that comes up at the last minute that the seller didn’t disclose and that the inspection missed.”

Darroll pursed her lips at this but said nothing. I had an idea what that meant; she was now thinking she might be smelling some bullshit on my part. She clicked onto another window. “You have your home listed as collateral.”

I nodded. “Yes, 504 South Cook Street. It was my parent’s house. I live there now. Barrington First National used to own the mortgage on it, a long time ago. Before my dad paid it off.” I didn’t volunteer that Dad paid off the house with the life insurance policy on mom after her car accident. This wasn’t America’s Got Talent; I didn’t want to share a sob story. “Since you already have Zillow up you can see that they currently estimate its value at about eight hundred thousand.”

Some more clacking from Darroll. “I see the house is currently administered by a trust.”

Well, crap, I thought. She had shifted off Zillow to find that bit of information.

“Family trust, yes,” I said.

“And you administer the trust?”

“I’m a beneficiary.”

“A beneficiary.”

“There are also my older siblings.”

“I see. How many of them are there?”

“Three.”

“And they’ve agreed to allow the house to be used as collateral?”

“We’ve discussed it and they seem positively inclined,” I lied.

Darroll caught the long explanation of something that should have been answered with “yes,” which was not in my favor. “I’ll need documentation of that from the trustee of the estate, notarized and preferably with the signatures of your siblings,” she said. “Do you think you can get that to me in the next couple of days?”

“I’ll get on it.”

Darroll noted this not-quite-affirmative response. “Will there be a problem getting that?”

“My sister Sarah is on vacation,” I said, and who knows, that might have actually been true. Sarah loved her vacations. “One of the smaller Hawaiian Islands. A resort that takes your cell phone when you arrive.”

“That actually sounds kinda great to me,” Darroll said. “But it does complicate things for you right now.” She put her hands down on her desk with a finality I didn’t think was great for me. “Mr. Fitzer, I’m going to be honest with you, here. Barrington First National has a new owner—”

“CerTrust,” I said. “I used to cover them at the paper.” Which was true. I didn’t hold a terribly high opinion of them. CerTrust didn’t achieve Wells Fargo levels of financial fuckery, but it wasn’t for lack of trying.

Darroll nodded at this and continued. “The loan policies at CerTrust are more stringent than they were here before the buyout. We want to encourage local business ownership, but we also have to keep a tighter eye on the fundamentals. You’re asking us to approve a multimillion-dollar loan with no percentage of the amount put up by you personally, backed by an asset that you don’t possess sole ownership of.”

“So you’re saying that’s a no,” I ventured.

“It’s not no. I’m saying it’s tough. I can’t approve a loan this size myself. I have to bring it up to our loan committee, which meets on Thursdays. If you can get that letter to me from your trustee in the next couple of days, that’ll help. But even then it’ll be tough. And after that, if our loan committee does give it a thumbs-up, it’ll have to go through another layer of approval at CerTrust.”

“They don’t trust your judgment here?”

Darroll smiled thinly. “They have different criteria for consideration, is how I like to put it.”

“So not no, but probably no, and it’ll take a week to say it.”

Darroll opened up her hands apologetically. “It’ll be tough,” she repeated. “I owe you that honesty.”

“Well,” I said. “I can’t fault you for being honest.”

“I know it’s not what you want to hear,” Darroll said. “Is there anyone you can get to come in as a partner with you?”

“You mean, who doesn’t have the same financial situation as I do?” I snorted at this. “Most of the people I know are ex-journalists like me. They’re either working as bartenders or substitute teachers.”

“Which do you do?”

“The latter for now. I was hoping to upgrade to the former.”

“What about your siblings or another family member? Maybe one of them will help you.”

“I think my siblings would think offering the house as collateral would be enough involvement,” I said, which was about as euphemistically as I could phrase that. “I have an uncle. Jake. He’s rich.”

“A rich uncle isn’t a bad thing,” Darroll said. “He might be looking for an investment opportunity.”

“It’s a nice thought,” I said. “Unfortunately he just passed away.”

“Oh, no,” Darroll said, looking graciously distraught. “I’m so sorry.”

“Thank you.”

“Are you all right?”

“I’m fine,” I said. “We weren’t close. He’s been out of my life since my mother passed away when I was a child.”

“Not to be indelicate, but . . . do you know if he left you a bequest?”

“It would be . . . surprising,” I said, using another euphemism.

“I’m sorry,” Darroll repeated. “It’s unfortunate you couldn’t have seen if he was interested before he passed on.”

“It would have been an awkward moment,” I said. “I mean, how is that going to look, me coming in and saying ‘Hey, Uncle Jake, sorry I haven’t seen you in person in almost thirty years, oh and by the way, can you cosign a three-million-dollar loan for me.’”

“You never know.”

I shook my head. “I’m pretty sure I do. Anyway, I don’t have too many positive feelings for him. The last time I had any contact with him at all was on my wedding day. He sent a pair of berry spoons as a gift, and a note that said ‘three years, six months.’”

Darroll frowned. “What did that mean?”

“I didn’t know at the time. I figured it out three and a half years later when my wife filed for divorce.”

“Holy shit,” Darroll said, and then put her hand to her mouth. “Sorry.”

“Don’t be. That was basically my reaction, too. So, yeah. the good news is, I kept the berry spoons after the breakup, so there’s that.” I stood up.

Darroll stood up too. “You’ll get that letter from your trustee to me,” she said.

“I’ll get on it,” I lied to her, one last time.

“Good luck on your novel,” she said, as I left her office. She didn’t mean that as a final stab in the kidneys, I’m sure. I felt the knife slide in anyway.

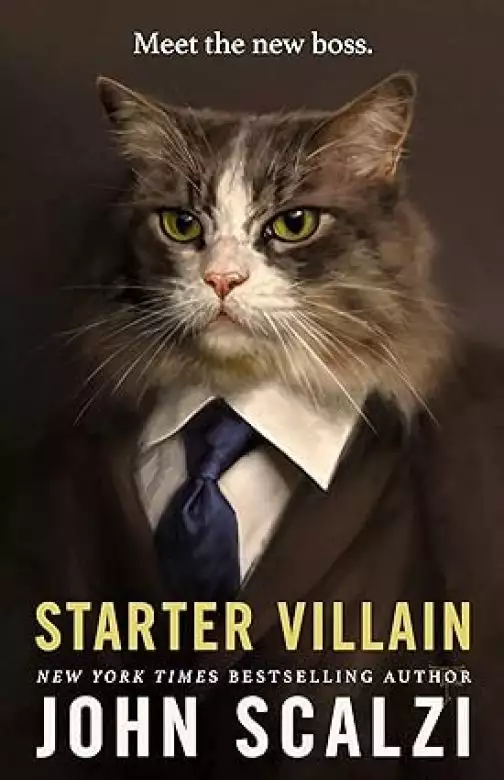

Copyright © 2023 from John Scalzi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved