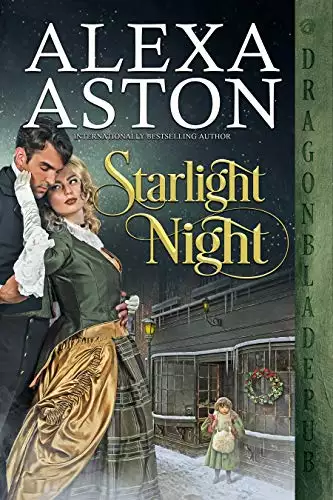

Starlight Night: An Historical Romance Novella

Book 6:

The St. Clairs

Can an earl and his countess convince an untrusting orphan to become part of their family?

Genres:

Regency Romance

Buy now

Available in:

- eBook

- Paperback

Synopsis

A child from the streets . . .

A couple with love in their hearts . . .

After her mother's death, six-year-old Lucy is sold by her father to Driskell, a drunk who forces her and two orphans, Jem and Boy, to work the streets of London as pickpockets. When Jem is killed in a carriage accident, Lucy and Boy run from their brutish owner. Separated from Boy as they flee, Lucy must now learn how to survive on her own.

Luke and Caroline St. Clair, Earl and Countess of Mayfield, are still madly in love after several years of marriage and have a growing brood of three children whom they adore. They also own the popular Evie's Bookstore and Tearoom. It is here Luke first encounters a small child all alone, peering into the store's windows, hungrily eying the books on display. Though young and seemingly innocent on first glance, he quickly realizes that she is an old soul and a street urchin who must live by her wits and learns she is an orphan who belongs to no one.

In the midst of celebrating the Christmas season with their family—and with love in their hearts for a child who needs them—can Luke and his countess convince a young, untrusting girl to become a part of their family?

Read free in Kindle Unlimited!

The St. Clairs

Book #1 Devoted to the Duke

Book #2 Midnight with the Marquess

Book #3 Embracing the Earl

Book #4 Defending the Duke

Book #5 Suddenly a St. Clair

Book #6 Starlight Night - Novella

(Note: This story was first published as part of the Bestselling Boxed set Stars are Brightly Shining, November 2019)

A couple with love in their hearts . . .

After her mother's death, six-year-old Lucy is sold by her father to Driskell, a drunk who forces her and two orphans, Jem and Boy, to work the streets of London as pickpockets. When Jem is killed in a carriage accident, Lucy and Boy run from their brutish owner. Separated from Boy as they flee, Lucy must now learn how to survive on her own.

Luke and Caroline St. Clair, Earl and Countess of Mayfield, are still madly in love after several years of marriage and have a growing brood of three children whom they adore. They also own the popular Evie's Bookstore and Tearoom. It is here Luke first encounters a small child all alone, peering into the store's windows, hungrily eying the books on display. Though young and seemingly innocent on first glance, he quickly realizes that she is an old soul and a street urchin who must live by her wits and learns she is an orphan who belongs to no one.

In the midst of celebrating the Christmas season with their family—and with love in their hearts for a child who needs them—can Luke and his countess convince a young, untrusting girl to become a part of their family?

Read free in Kindle Unlimited!

The St. Clairs

Book #1 Devoted to the Duke

Book #2 Midnight with the Marquess

Book #3 Embracing the Earl

Book #4 Defending the Duke

Book #5 Suddenly a St. Clair

Book #6 Starlight Night - Novella

(Note: This story was first published as part of the Bestselling Boxed set Stars are Brightly Shining, November 2019)

Release date: July 18, 2020

Publisher: Dragonblade Publishing, Inc.

Print pages: 42

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.