- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

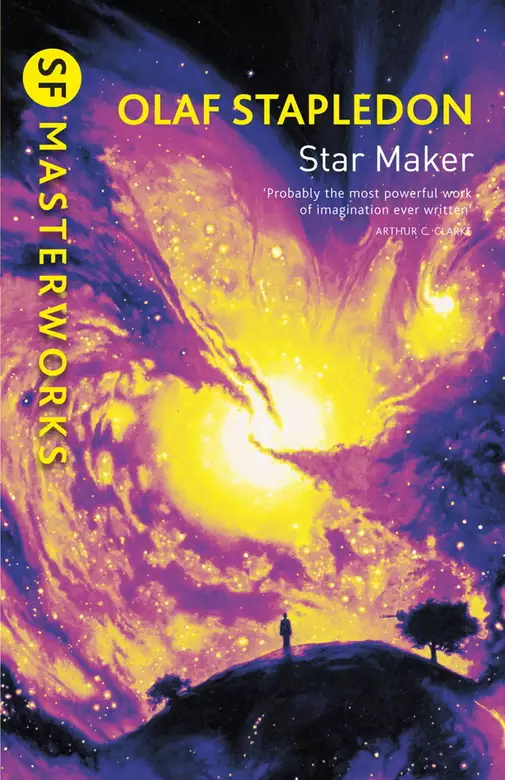

Synopsis

One moment a man sits on a suburban hill, gazing curiously at the stars. The next, he is whirling through the firmament, and perhaps the most remarkable of all science fiction journeys has begun. Even Stapledon's other great work, Last and First Men pales in ambition next to Star Maker which presents nothing less than an entire imagined history of life in the universe, encompassing billions of years.

Release date: November 14, 2011

Publisher: Audible Studios

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Star Maker

Olaf Stapledon

Star Maker is the most wonderful novel I have ever read. It retains its wonder on successive readings, and repays study.

To put it at its simplest, the story of the book is the story of a quest, but a quest on a cosmic and superhuman scale. The “I” of the book projects his spirit away from this Earth and “the world’s delirium” into the universe, to encounter other worlds, other beings, other classes of beings, finally to confront the creator of the universe itself, the Star Maker, and be permitted communication with it. Nothing could be simpler—or more ambitious.

In his original preface to Star Maker, the author states that this is not a novel at all. True, it more resembles an attempt to create myth on the grandest possible scale—a myth for our time that will appease both the scientist and the mystic in us. That is to say, a myth for the two hemispheres of mankind’s divided brain. The nobility of this attempt sets Star Maker apart from both the modern novel and science fiction, which it superficially resembles. The intention is to instruct as well as to entertain, to imagine as well as to synthesize.

As we might expect, the author of such an astonishing book is himself something of a mystery. William Olaf Stapledon (1886–1950) has been depicted by some critics as a feeble kind of fellow. On the contrary, I believe he was a man of marked character, an athlete in his youth at Oxford, and certainly a brave man to have embarked on an enterprise as considerable as the present book. He may have had his peculiarities, but an ordinary man in the street would hardly create a work like this!

Stapledon was an Englishman whose childhood was divided between England and Egypt, where his father was employed by a shipping line. This pinch of exile probably helped forge the detachment so noticeable in his writing. His first novel (though again the term novel is questionable) was Last and First Men, published in London in 1930.

That book won enthusiastic critical reviews and remains Stapledon’s most famous work. Yet acceptance even of Last and First Men is as uncertain as Stapledon’s reputation—preserved by science fiction readers, those worldly visionaries. It faded from recognition at one time, to be revived only when the present writer persuaded Penguin Books to reissue it with his Introduction in 1963. Covering as it does the next five billion years, Last and First Men is the most thorough and amazing future history ever written. Yet it was to be eclipsed in virtuosity as well as scale seven years later, when Star Maker appeared. Star Maker is grander in theme, more felicitous in style, subtler in approach—not to mention more overwhelming in imaginative power.

As for Stapledon’s courage, at the least he was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his service in World War I, when he worked as an ambulance driver in the mud and muck of Flanders. Ambulance driving was an appropriate occupation, well suited to a man of pacifist inclinations who nevertheless felt compelled to play a part in that ghastly struggle in which the Old Centuries were irrevocably severed from the New.

The quality of aloofness in Stapledon’s character was not of his own choosing; whatever difficulties the quality brought him in ordinary life, it made him the kind of writer he became. Much though he feared that the war would undermine civilization—as it undoubtedly did—he appreciated that it gave him the chance to work as one with his fellows. In his strange successor to Last and First Men, entitled Last Men In London, Stapledon has his protagonist, Paul, say that he entered the war “to accept as far as possible on the one hand the great common agony, and on the other the private loneliness of those who cannot share the deepest passions of their fellows.” Star Maker is also chock-a-bloc with great common agonies and private lonelinesses—often the private lonelinesses of entire solar communities.

Madness, akin to loneliness, is often in Stapledon’s mind. The endless vistas of galaxy after prodigal galaxy threaten the intellect:

As we searched up and down time and space, discovering more and more of the rare grains called planets, we watched race after race struggle to a certain degree of lucid consciousness, only to succumb to some external accident or, more often, to some flaw in its own nature, we were increasingly oppressed by a sense of the futility, the planlessness of the cosmos.

This sombre mood, owing much to the pessimism of Schopenhauer and the conviction that God was dead or an illusion, is more characteristic of the higher thinkers of the late nineteenth century than the optimistic technophiles of the twentieth. There are, however, times when we are reminded that Stapledon explored at a very early date the standby of ambitious science fiction writers from E. E. Smith onward, galactic empires at war:

Germinating in regions far apart, these empires easily mastered any sub-utopian worlds that lay within reach. Thus they spread from one planetary system to another, till at last empire made contact with empire.

Then followed wars such as had never before occurred in our galaxy. Fleets of worlds, natural and artificial, manoeuvred among the stars to outwit one another, and destroyed one another with long-range jets of sub-atomic energy. As the tides of battle swung hither and thither through space, whole planetary systems were annihilated. Many a world-spirit found a sudden end. Many a lowly race that had no part in the strife was slaughtered in the celestial warfare that raged around it.

But any similarities between Stapledon’s irresistible sweep of events and conventional science fiction is purely coincidental. Stapledon’s imagination is omnivorous. After discoursing with the minds of great nebulae, the questing spirit goes on to achieve discourse with the Star Maker itself. The finely sustained climax of the book is the Maker’s description of the series of universes with which he is experimenting, of which ours is but one in an almost infinite line. Where does one look in all English prose for a parallel with the magnificent Chapter 15?

An introduction should go no further than this in outlining the many astonishments which the reader is to undergo. But it is worth noting one reason why so many readers are unable to confront Stapledon squarely. He is too challenging for comfort. The scientifically minded mistrust the reverence in the work; the religious shrink from the idea of a creator who neither loves nor has need of love from his creations. To my mind, this intransigent position is in fact the delight of the book, and proves Stapledon’s courage. Like his Star Maker, Stapledon inculcates a similar independence in his readers. He is not asking to be loved. He does not love. His work is there. We accept it as we will.

Because of this admirably Parnassian attitude, Stapledon has influenced few writers directly. To show his influence, a writer must have imbibed him when young and demonstrate in his later writing a sense of cosmic process indifferent to the ambitions of humankind. Arthur C. Clarke has claimed to be influenced by Stapledon, and we may believe him. I also came on his writing early, in the middle of a world war, when that dispassionate voice carried the shock of sanity. (Galaxies Like Grains of Sand is imitation Stapledon.)

The writers who helped form Stapledon’s characteristic utterance are most probably philosophical and political writers. There was also, of course, H. G. Wells, twenty years Stapledon’s senior. Otherwise, one might name Dante and the author of Paradise Lost. But the most obvious influence appears to be Winwood Reade, the once-celebrated author of The Martyrdom of Man, a work published in 1872 and frequently reprinted over the succeeding eighty years. Reade’s work ranges freely over the entire history of mankind, and is at once scientific and political. Wells described it as “an extraordinarily inspiring presentation of human history as one consistent process.” It would be this view of life as a process that appealed to Stapledon, as it did to Wells.

The Martyrdom of Man roused great antagonism in its time, in the main because of its attack upon religion. Reade did, indeed, put God in his place, as a passage such as the following suggests:

The arithmetical arrangement of the gods depends entirely upon the intellectual faculties of the people concerned. In the period of thing-worship, as it may be termed, every brook, tree, hill, and star is itself a living creature, benevolent or malignant, asleep or awake. In the next stage every object and phenomenon is inhabited or presided over by a genius or spirit, and with some nations the virtues and the vices are also endowed with personality. As the reasoning powers of men expand their gods diminish in number and rule over larger areas, till finally it is perceived that there is unity in nature, that everything which exists is a part of one harmonious whole. It is then asserted that one being manufactured the world and rules over it supreme. But at first the Great Being is distant and indifferent, “a god sitting outside the universe”; and the old gods become viceroys to whom he has deputed the government of the world. They are afterwards degraded to the rank of messengers or angels, and it is believed that God is everywhere present; that he fills the earth and sky; that from him directly proceeds both the evil and the good. In some systems of belief, however, he is believed to be the author of good alone, and the dominion of evil is assigned to a rebellious angel or a rival god.

This extract is included not only because I hope to find others to share my enthusiasm for Winwood Reade, but because one can see Olaf Stapledon chuckling with appreciation over such downgrading of the deity.

Stapledon takes that thought further. Light years further.

Whatever it may be—novel, myth, prose poem, vision—Star Maker remains light years ahead, something toward which the rest of us are still travelling.

Publisher’s Note:

The Star Maker Glossary included in this 50th Anniversary Edition was intended for the original edition of the book.

One night when I had tasted bitterness I went out on to the hill. Dark heather checked my feet. Below marched the suburban street lamps. Windows, their curtains drawn, were shut eyes, inwardly watching the lives of dreams. Beyond the sea’s level darkness a lighthouse pulsed. Overhead, obscurity.

I distinguished our own house, our islet in the tumultuous and bitter currents of the world. There, for a decade and a half, we two, so different in quality, had grown in and in to one another, for mutual support and nourishment, in intricate symbiosis. There daily we planned our several undertakings, and recounted the day’s oddities and vexations. There letters piled up to be answered, socks to be darned. There the children were born, those sudden new lives. There, under that roof, our own two lives, recalcitrant sometimes to one another, were all the while thankfully one, one larger, more conscious life than either alone.

All this, surely, was good. Yet there was bitterness. And bitterness not only invaded us from the world; it welled up also within our own magic circle. For horror at our futility, at our own unreality, and not only at the world’s delirium, had driven me out on to the hill.

We were always hurrying from one little urgent task to another, but the upshot was insubstantial. Had we, perhaps, misconceived our whole existence? Were we, as it were, living from false premises? And in particular, this partnership of ours, this seemingly so well-based fulcrum for activity in the world, was it after all nothing but a little eddy of complacent and ingrown domesticity, ineffectively whirling on the surface of the great flux, having in itself no depth of being, and no significance? Had we perhaps after all deceived ourselves? Behind those rapt windows did we, like so many others, indeed live only a dream? In a sick world even the hale are sick. And we two, spinning our little life mostly by rote, seldom with clear cognizance, seldom with firm intent, were products of a sick world.

Yet this life of ours was not all sheer and barren fantasy. Was it not spun from the actual fibres of reality, which we gathered in with all the comings and goings through our door, all our traffic with the suburb and the city and with remoter cities, and with the ends of the earth? And were we not spinning together an authentic expression of our own nature? Did not our life issue daily as more or less firm threads of active living, and mesh itself into the growing web, the intricate, ever-proliferating pattern of mankind?

I considered ‘us’ with quiet interest and a kind of amused awe. How could I describe our relationship even to myself without either disparaging it or insulting it with the tawdry decoration of sentimentality? For this our delicate balance of dependence and independence, this coolly critical, shrewdly ridiculing, but loving mutual contact, was surely a microcosm of true community, was after all in its simple style an actual and living example of that high goal which the world seeks.

The whole world? The whole universe? Overheard, obscurity unveiled a star. One tremulous arrow of light, projected how many thousands of years ago, now stung my nerves with vision, and my heart with fear. For in such a universe as this what significance could there be in our fortuitous, our frail, our evanescent community?

But now irrationally I was seized with a strange worship, not, surely of the star, that mere furnace which mere distance falsely sanctified, but of something other, which the dire contrast of the star and us signified to the heart. Yet what, what could thus be signified? Intellect, peering beyond the star, discovered no Star Maker, but only darkness; no Love, no Power even, but only Nothing. And yet the heart praised.

Impatiently I shook off this folly, and reverted from the inscrutable to the familiar and the concrete. Thrusting aside worship, and fear also and bitterness, I determined to examine more coldly this remarkable ‘us’, this surprisingly impressive datum, which to ourselves remained basic to the universe, though in relation to the stars it appeared so slight a thing.

Considered even without reference to our belittling cosmical background, we were after all insignificant, perhaps ridiculous. We were such a commonplace occurrence, so trite, so respectable. We were just a married couple, making shift to live together without undue strain. Marriage in our time was suspect. And ours, with its trivial romantic origin, was doubly suspect.

We had first met when she was a child. Our eyes encountered. She looked at me for a moment with quiet attention; even, I had romantically imagined, with obscure, deep-lying recognition. I, at any rate, recognized in that look (so I persuaded myself in my fever of adolescence) my destiny. Yes! How predestinate had seemed our union! Yet now, in retrospect, how accidental! True, of course, that as a long-married couple we fitted rather neatly, like two close trees whose trunks have grown upwards together as a single shaft, mutually distorting, but mutually supporting. Coldly I now assessed her as merely a useful, but often infuriating adjunct to my personal life. We were on the whole sensible companions. We left one another a certain freedom, and so we were able to endure our proximity.

Such was our relationship. Stated thus it did not seem very significant for the understanding of the universe. Yet in my heart I knew that it was so. Even the cold stars, even the whole cosmos with all its inane immensities could not convince me that this our prized atom of community, imperfect as it was, short-lived as it must be, was not significant.

But could this indescribable union of ours really have any significance at all beyond itself? Did it, for instance, prove that the essential nature of all human beings was to love, rather than to hate and fear? Was it evidence that all men and women the world over, though circumstance might prevent them, were at heart capable of supporting a world-wide, love-knit community? And further, did it, being itself a product of the cosmos, prove that love was in some way basic to the cosmos itself? And did it afford, through its own felt intrinsic excellence, some guarantee that we two, its frail supporters, must in some sense have eternal life? Did it, in fact, prove that love was God, and God awaiting us in his heaven?

No! Our homely, friendly, exasperating, laughter-making, undecorated though most prized community of spirit proved none of these things. It was no certain guarantee of anything but its own imperfect rightness. It was nothing but a very minute, very bright epitome of one out of the many potentialities of existence. I remembered the swarms of the unseeing stars. I remembered the tumult of hate and fear and bitterness which is man’s world. I remembered, too, our own not infrequent discordancy. And I reminded myself that we should very soon vanish like the flurry that a breeze has made on still water.

Once more there came to me a perception of the strange contrast of the stars and us. The incalculable potency of the cosmos mysteriously enhanced the rightness of our brief spark of community, and of mankind’s brief, uncertain venture. And these in turn quickened the cosmos.

I sat down on the heather. Overhead obscurity was now in full retreat. In its rear the freed population of the sky sprang out of hiding, star by star.

On every side the shadowy hills or the guessed, featureless sea extended beyond sight. But the hawk-flight of imagination followed them as they curved downward below the horizon. I perceived that I was on a little round grain of rock and metal, filmed with water and with air, whirling in sunlight and darkness. And on the skin of that little grain all the swarms of men, generation by generation, had lived in labour and blindness, with intermittent joy and intermittent lucidity of spirit. And all their history, with its folk-wanderings, its empires, its philosophies, its proud sciences, its social revolutions, its increasing hunger for community, was but a flicker in one day of the lives of stars.

If one could know whether among that glittering host there were here and there other spirit-inhabited grains of rock and metal, whether man’s blundering search for wisdom and for love was a sole and insignificant tremor, or part of a universal movement!

Overhead obscurity was gone. From horizon to horizon the sky was an unbroken spread of stars. Two planets stared, unwinking. The more obtrusive of the constellations asserted their individuality. Orion’s foursquare shoulders and feet, his belt and sword, the Plough, the zigzag of Cassiopeia, the intimate Pleiades, all were duly patterned on the dark. The Milky Way, a vague hoop of light, spanned the sky.

Imagination completed what mere sight could not achieve. Looking down, I seemed to see through a transparent plant, through heather and solid rock, through the buried graveyards of vanished species, down through the molten flow of basalt, and on into the Earth’s core of iron; then on again, still seemingly downwards, through the southern strata to the southern ocean and lands, past the roots of gum trees and the feet of the inverted antipodeans, through their blue, sun-pierced awning of day, and out into the eternal night, where sun and stars are together. For there, dizzyingly far below me, like fishes in the depth of a lake, lay the nether constellations. The two domes of the sky were fused into one hollow sphere, star-peopled, black, even beside the blinding sun. The young moon was a curve of incandescent wire. The completed hoop of the Milky Way encircled the universe.

In a strange vertigo, I looked for reassurance at the little glowing windows of our home. There they still were; and the whole suburb, and the hills. But stars shone through all. It was as though all terrestrial things were made of glass, or of some more limpid, more ethereal vitreosity. Faintly the church clock chimed for midnight. Dimly, receding, it tolled the first stroke.

Imagination was now stimulated to a new, strange mode of perception. Looking from star to star, I saw the heaven no longer as a jewelled ceiling and floor, but as depth beyond flashing depth of suns. And though for the most part the great and familiar lights of the sky stood forth as our near neighbours, some brilliant stars were seen to be in fact remote and mighty, while some dim lamps were visible only because they were so near. On every side the middle distance was crowded with swarms and streams of stars. But even these now seemed near; for the Milky Way had receded into an incomparably greater distance. And through gaps in its nearer parts appeared vista beyond vista of luminous mists, and deep perspectives of stellar populations.

The universe in which fate had set me was no spangled chamber, but a perceived vortex of star-streams. No! It was more. Peering between the stars into the outer darkness, I saw also, as mere flecks and points of light, other such vortices, such galaxies, sparsely scattered in the void, depth beyond depth, so far afield that even the eye of imagination could find no limits to the cosmical, the all-embracing galaxy of galaxies. The universe now appeared to me as a void wherein floated rare flakes of snow, each flake a universe.

Gazing at the faintest and remotest of all the swarm of universes, I seemed, by hypertelescopic imagination, to see it as a population of suns; and near one of those suns was a planet, and on that planet’s dark side a hill, and on that hill myself. For our astronomers assure us that in this boundless finitude which we call the cosmos the straight lines of light lead not to infinity but to their source. Then I remembered that, had my vision depended on physical light, and not on the light of imagination, the rays coming thus to me ‘round’ the cosmos would have revealed, not myself, but events that had ceased long before the Earth, or perhaps even the Sun, was formed.

But now, once more shunning these immensities, I looked again for the curtained windows of our home, which, though star-pierced, was still more real to me than all the galaxies. But our home had vanished, with the whole suburb, and the hills too, and the sea. The very ground on which I had been sitting was gone. Instead there lay far below me an insubstantial gloom. And I myself was seemingly disembodied, for I could neither see nor touch my own flesh. And when I willed to move my limbs, nothing happened. I had no limbs. The familiar inner perceptions of my body, and the headache which had oppressed me since morning, had given way to a vague lightness and exhilaration.

When I realized fully the change that had come over me, I wondered if I had died, and was entering some wholly unexpected new existence. Such a banal possibility at first exasperated me. Then with sudden dismay I understood that if indeed I had died I should not return to my prized, concrete atom of community. The violence of my distress shocked me. But soon I comforted myself with the thought that after all I was probably not dead, but in some sort of trance, from which I might wake at any minute. I resolved, therefore, not to be unduly alarmed by this mysterious change. With scientific interest I would observe all that happened to me.

I noticed that the obscurity which had taken the place of the ground was shrinking and condensing. The nether stars were no longer visible through it. Soon the earth below me was like a huge circular table-top, a broad disc of darkness surrounded by stars. I was apparently soaring away from my native planet at incredible speed. The sun, formerly visible to imagination in the nether heaven, was once more physically eclipsed by the Earth. Though by now I must have been hundreds of miles above the ground, I was not troubled by the absence of oxygen and atmospheric pressure. I experienced only an increasing exhilaration and a delightful effervescence of thought. The extraordinary brilliance of the stars excited me. For, whether through the absence of obscuring air, or through my own increased sensitivity, or both, the sky had taken on an unfamiliar aspect. Every star had seemingly flared up into higher magnitude. The heavens blazed. The major stars were like the headlights of a distant car. The Milky Way, no longer watered down with darkness, was an encircling, granular river of light.

Presently, along the Planet’s eastern limb, now far below me, there appeared a faint line of luminosity; which, as I continued to soar, warmed here and there to orange and red. Evidently I was travelling not only upwards but eastwards, and swinging round into the day. Soon the sun leapt into view, devouring the huge crescent of dawn with his brilliance. But as I sped on, sun and planet were seen to drift apart, while the thread of dawn thickened into a misty breadth of sunlight. This increased, like a visibly waxing moon, till half the planet was illuminated. Between the areas of night and day, a belt of shade, warm-tinted, broad as a sub-continent, now marked the area of dawn. As I continued to rise and travel eastwards, I saw the lands swing westward along with the day, till I was over the Pacific and high noon.

The Earth appeared now as a great bright orb hundreds of times larger than the full moon. In its centre a dazzling patch of light was the sun’s image reflected in the ocean. The planet’s circumference was an indefinite breadth of luminous haze, fading into the surrounding blackness of space. Much of the northern hemisphere, tilted somewhat towards me, was an expanse of snow and cloud-tops. I could trace parts of the outlines of Japan and China, their vague browns and greens indenting the vague blues and greys of the ocean. Towards the equator, where the air was clearer, the ocean was dark. A little whirl of brilliant cloud was perhaps the upper surface of a hurricane. The Philippines and New Guinea were precisely mapped. Australia faded into the hazy southern limb.

The spectacle before me was strangely moving. Personal anxiety was blotted out by wonder and admiration; for the sheer beauty of our planet surprised me. It was a huge pearl, set in spangled ebony. It was nacreous, it was an opal. No, it was far more lovely than any jewel. Its patterned colouring was more subtle, more ethereal. It displayed the delicacy and brilliance, the intricacy and harmony of a live thing. Strange that in my remoteness I seemed to feel, as never before, the vital presence of Earth as of a creature alive but tranced and obscurely yearning to wake.

I reflected that not one of the visible features of this celestial and living gem revealed the presence of man. Displayed before me, though invisible, were some of the most congested centres of human population. There below me lay huge industrial regions, blackening the air with smoke. Yet all this thronging life and humanly momentous enterprise had made no mark whatever on the features of the planet. From this high lookout the Earth would have appeared no different before the dawn of man. No visiting angel, or explorer from another planet, could have guessed that this bland orb teemed with vermin, with world-mastering, self-torturing, incipiently angelic beasts.

While I was thus contemplating my native planet, I continued to soar through space. The Earth was visibly shrinking into the distance, and as I raced eastwards, it seemed to be rotating beneath me. All its features swung westwards, till presently sunset and the Mid-Atlantic appeared upon its eastern limb, and then the night. Within a few minutes, as it seemed to me, the planet had become an immense half-moon. Soon it was a misty, dwindling crescent, beside the sharp and minute crescent of its satellite.

With amazeme. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...