- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

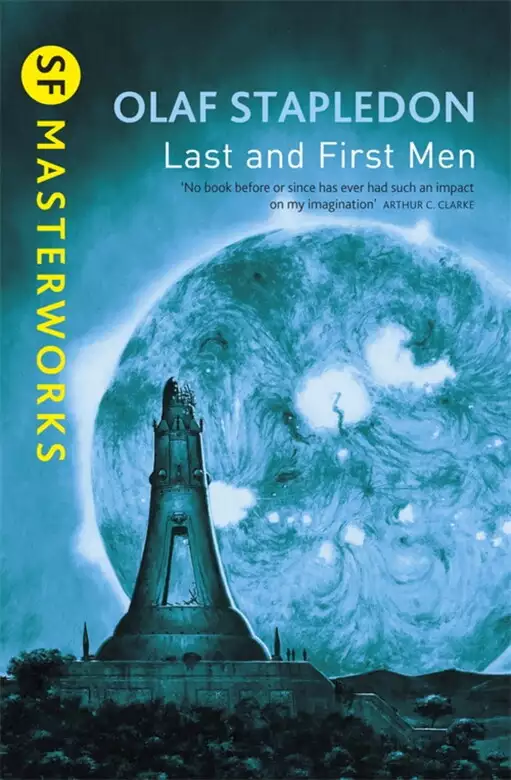

First published nearly 70 years ago, this masterpiece is regarded as one of the most influential science fiction novels of the 20th century. Olaf Stapledon creates a history of the evolution of humankind over the next two billion years, and has lots of it right! It's so vast; it brings the concept of `time' closer to the human experience. "No book before or since has ever had such an impact upon my imagination," declared 2001 author Arthur C. Clarke of this masterpiece of science fiction. An imaginative, ambitious history of humanity's future that spans billions of years, this 1930 epic abounds in prescient speculations. Not only a must-read for scholars of the genre but even for those who want to look beyond their own immortality, as well as our civilizations immortality.

Release date: December 30, 2013

Publisher: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

Print pages: 297

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Last And First Men

Olaf Stapledon

It received good reviews from the major literary pundits of the day. ‘As original as the solar system,’ Hugh Walpole commented. Arnold Bennett cited the ‘tremendous and beautiful imagination’. A politician, bumped from office and relying on writing for his income, wrote a praising review – Winston S. Churchill appreciated its scope.

Not that the author totally neglected his tortured times. ‘I have tried to make the story relevant to the change that is taking place today in man’s outlook,’ he remarked in his preface. ‘I have imagined the triumph of the cruder sort of Americanism over all that is best and most promising in American culture.’ He evidently hoped to tie his grand-scale speculations to current great-power politics, to find ‘an early turning point in the long drama of Man.’

Interestingly, this is precisely what makes the book – not a novel, perhaps, but surely science fiction – seem awkward and naïve in its opening movements. Olaf Stapledon proved to be completely wrong about the near term. Virtually everything he says about America and Germany is startlingly off base. He seems to have had a smoldering dislike of both nations, Germany because of World War I and America because it embodied capitalism in the eyes of everyone. His Marxism, which remained his only irrational faith throughout his life, told him that surely the United States could never be a positive influence. Ironically, and with comic justice, this first complete edition of Last and First Men in over half a century is being published by an American firm, following on a strikingly successful fresh edition of Star Maker, Stapledon’s masterpiece.

But if he was wrong in matters of near interest, he was plentifully powerful when the larger canvas opened before him. Stapledon had studied the principal scientific discovery of the nineteenth century, the Darwin-Wallace idea of evolution, and projected it onto the vast scale of our future, envisioning the progression of intelligence as another element in the natural scheme. In his hands the pressures of environment became the blunt facts of planetary evolution, the dynamics of worlds. He had followed the theories recently developed by astronomers, which described the physical evolution of stars from early compression to final death-throes, the slow massive workings of red giants and white dwarves. This ability to take the ideas of the era and forge them into a new secular vision marked Stapledon as wholly original.

But his view was not what we usually mean by ‘humanistic’. Schopenhauer’s philosophy of being and Spengler’s somewhat clock-worky mechanisms of cyclic history run through this work. Man is not the measure of all things in this stretched vision. He is ‘a fledgling caught in a brush fire,’ forced forward by nature’s blind laws toward a fate he comprehends but never quite believes, until the final trump is played and the Last Man falls.

Nor is this Man holy or God-sanctified. ‘The music of the spheres passes over him, through him, and is not heard.’ Though Man the Scientist can glimpse larger truths, even his marvelling is transitory. Stapledon was one of those ‘intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic’ in H. G. Wells’ unforgettable description of the Martians.

Brian Aldiss terms this book and Star Maker ‘great classical ontological epic prose poems’, a precise and yet huge definition of what makes Stapledon so fascinating. These two books gripped the imaginations of figures such as novelist Arthur C. Clarke and physicist Freeman Dyson. These men stand, along with their precursors H. G. Wells and scientist J. D. Bernal, in a grand tradition of English thinkers who always strove toward the largest scale possible for their work. The particularly British tone to all their works has given a cool cast to the very way we think of the future.

In this complete edition – the first in the United States – I would advise the reader to simply skip the first four parts and begin with The Fall of the First Men. This eliminates the antique quality of the book and also tempers the rather repetitive cycle of rise and fall that becomes rather monotonous. The book gathers and grows as it rolls forward, though, achieving a sweeping beauty and moral resonance. I believe no one can remain unaffected as they near the end of our race, and ponder the issues that must afflict all knowing, mortal beings: ‘Great are the stars, and man is of no account to them … But when he is done he will not be nothing, not as though he had never been; for he is eternally a beauty in the eternal form of things.’ Yet we do matter. ‘Man himself, at the very least, is music, a brave theme that makes music also of its vast accompaniment, its matrix of storms and stars.’

Gregory Benford December 15, 1987

This is a work of fiction. I have tried to invent a story which may seem a possible, or at least not wholly impossible, account of the future of man; and I have tried to make that story relevant to the change that is taking place today in man’s outlook.

To romance of the future may seem to be indulgence in ungoverned speculation for the sake of the marvellous. Yet controlled imagination in this sphere can be a very valuable exercise for minds bewildered about the present and its potentialities. Today we should welcome, and even study, every serious attempt to envisage the future of our race; not merely in order to grasp the very diverse and often tragic possibilities that confront us, but also that we may familiarize ourselves with the certainty that many of our most cherished ideals would seem puerile to more developed minds. To romance of the far future, then, is to attempt to see the human race in its cosmic setting, and to mould our hearts to entertain new values.

But if such imaginative construction of possible futures is to be at all potent, our imagination must be strictly disciplined. We must endeavour not to go beyond the bounds of possibility set by the particular state of culture within which we live. The merely fantastic has only minor power. Not that we should seek actually to prophesy what will as a matter of fact occur; for in our present state such prophecy is certainly futile, save in the simplest matters. We are not to set up as historians attempting to look ahead instead of backwards. We can only select a certain thread out of the tangle of many equally valid possibilities. But we must select with a purpose. The activity that we are undertaking is not science, but art; and the effect that it should have on the reader is the effect that art should have.

Yet our aim is not merely to create aesthetically admirable fiction. We must achieve neither mere history, nor mere fiction, but myth. A true myth is one which, within the universe of a certain culture (living or dead), expresses richly, and often perhaps tragically, the highest admirations possible within that culture. A false myth is one which either violently transgresses the limits of credibility set by its own cultural matrix, or expresses admirations less developed than those of its culture’s best vision. This book can no more claim to be true myth than true prophecy. But it is an essay in myth creation.

The kind of future which is here imagined, should not, I think, seem wholly fantastic, or at any rate not so fantastic as to be without significance, to modern Western individuals who are familiar with the outlines of contemporary thought. Had I chosen matter in which there was nothing whatever of the fantastic, its very plausibility would have rendered it unplausible. For one thing at least is almost certain about the future, namely, that very much of it will be such as we should call incredible. In one important respect, indeed, I may perhaps seem to have strayed into barren extravagance. I have supposed an inhabitant of the remote future to be communicating with us of today. I have pretended that he has the power of partially controlling the operations of minds now living, and that this book is the product of such influence. Yet even this fiction is perhaps not wholly excluded by our thought. I might, of course, easily have omitted it without more than superficial alteration of the theme. But its introduction was more than a convenience. Only by some such radical and bewildering device could I embody the possibility that there may be more in time’s nature than is revealed to us. Indeed, only by some such trick could I do justice to the conviction that our whole present mentality is but a confused and halting first experiment.

If ever this book should happen to be discovered by some future individual, for instance by a member of the next generation sorting out the rubbish of his predecessors, it will certainly raise a smile; for very much is bound to happen of which no hint is yet discoverable. And indeed even in our generation circumstances may well change so unexpectedly and so radically that this book may very soon look ridiculous. But no matter. We of today must conceive our relation to the rest of the universe as best we can; and even if our images must seem fantastic to future men, they may none the less serve their purpose today.

Some readers, taking my story to be an attempt at prophecy, may deem it unwarrantably pessimistic. But it is not prophecy; it is myth, or an essay in myth. We all desire the future to turn out more happily than I have figured it. In particular we desire our present civilization to advance steadily toward some kind of Utopia. The thought that it may decay and collapse, and that all its spiritual treasure may be lost irrevocably, is repugnant to us. Yet this must be faced as at least a possibility. And this kind of tragedy, the tragedy of a race, must, I think, be admitted in any adequate myth.

And so, while gladly recognizing that in our time there are strong seeds of hope as well as of despair, I have imagined for aesthetic purposes that our race will destroy itself. There is today a very earnest movement for peace and international unity; and surely with good fortune and intelligent management it may triumph. Most earnestly we must hope that it will. But I have figured things out in this book in such a manner that this great movement fails. I suppose it incapable of preventing a succession of national wars; and I permit it only to achieve the goal of unity and peace after the mentality of the race has been undermined. May this not happen! May the League of Nations, or some more strictly cosmopolitan authority, win through before it is too late! Yet let us find room in our minds and in our hearts for the thought that the whole enterprise of our race may be after all but a minor and unsuccessful episode in a vaster drama, which also perhaps may be tragic.

American readers, if ever there are any, may feel that their great nation is given a somewhat unattractive part in the story. I have imagined the triumph of the cruder sort of Americanism over all that is best and most promising in American culture. May this not occur in the real world! Americans themselves, however, admit the possibility of such an issue, and will, I hope, forgive me for emphasizing it, and using it as an early turning-point in the long drama of Man.

Any attempt to conceive such a drama must take into account whatever contemporary science has to say about man’s own nature and his physical environment. I have tried to supplement my own slight knowledge of natural science by pestering my scientific friends. In particular, I have been very greatly helped by conversation with Professors P. G. H. Boswell, J. Johnstone, and J. Rice, of Liverpool. But they must not be held responsible for the many deliberate extravagances which, though they serve a purpose in the design, may jar upon the scientific ear.

To Dr L. A. Reid I am much indebted for general comments, and to Mr E. V. Rieu for many very valuable suggestions. To Professor and Mrs L. C. Martin, who read the whole book in manuscript, I cannot properly express my gratitude for constant encouragement and criticism. To my wife’s devastating sanity I owe far more than she supposes.

Before closing this preface I would remind the reader that throughout the following pages the speaker, the first person singular, is supposed to be, not the actual writer, but an individual living in the extremely distant future.

O. S.

WEST KIRBY

July, 1930

BY ONE OF THE LAST MEN

This book has two authors, one contemporary with its readers, the other an inhabitant of an age which they would call the distant future. The brain that conceives and writes these sentences lives in the time of Einstein. Yet I, the true inspirer of this book, I who have begotten it upon that brain, I who influence that primitive being’s conception, inhabit an age which, for Einstein, lies in the very remote future.

The actual writer thinks he is merely contriving a work of fiction. Though he seeks to tell a plausible story, he neither believes it himself, nor expects others to believe it. Yet the story is true. A being whom you would call a future man has seized the docile but scarcely adequate brain of your contemporary, and is trying to direct its familiar processes for an alien purpose. Thus a future epoch makes contact with your age. Listen patiently; for we who are the Last Men earnestly desire to communicate with you, who are members of the First Human Species. We can help you, and we need your help.

You cannot believe it. Your acquaintance with time is very imperfect, and so your understanding of it is defeated. But no matter. Do not perplex yourselves about this truth, so difficult to you, so familiar to us of a later aeon. Do but entertain, merely as a fiction, the idea that the thought and will of individuals future to you may intrude, rarely and with difficulty, into the mental processes of some of your contemporaries. Pretend that you believe this, and that the following chronicle is an authentic message from the Last Men. Imagine the consequences of such a belief. Otherwise I cannot give life to the great history which it is my task to tell.

When your writers romance of the future, they too easily imagine a progress toward some kind of Utopia, in which beings like themselves live in unmitigated bliss among circumstances perfectly suited to a fixed human nature. I shall not describe any such paradise. Instead, I shall record huge fluctuations of joy and woe, the results of changes not only in man’s environment but in his fluid nature. And I must tell how, in my own age, having at last achieved spiritual maturity and the philosophic mind, man is forced by an unexpected crisis to embark on an enterprise both repugnant and desperate.

I invite you, then, to travel in imagination through the aeons that lie between your age and mine. I ask you to watch such a history of change, grief, hope, and unforeseen catastrophe, as has nowhere else occurred, within the girdle of the Milky Way. But first, it is well to contemplate for a few moments the mere magnitudes of cosmical events. For, compressed as it must necessarily be, the narrative that I have to tell may seem to present a sequence of adventures and disasters crowded together, with no intervening peace. But in fact man’s career has been less like a mountain torrent hurtling from rock to rock, than a great sluggish river, broken very seldom by rapids. Ages of quiescence, often of actual stagnation, filled with the monotonous problems and toils of countless almost identical lives, have been punctuated by rare moments of racial adventure. Nay, even these few seemingly rapid events themselves were in fact often long-drawn-out and tedious. They acquire a mere illusion of speed from the speed of the narrative.

The receding depths of time and space, though they can indeed be haltingly conceived even by primitive minds, cannot be imaged save by beings of a more ample nature. A panorama of mountains appears to naïve vision almost as a flat picture, and the starry void is a roof pricked with light. Yet in reality, while the immediate terrain could be spanned in an hour’s walking, the sky-line of peaks holds within it plain beyond plain. Similarly with time. While the near past and the near future display within them depth beyond depth, time’s remote immensities are foreshortened into flatness. It is almost inconceivable to simple minds that man’s whole history should be but a moment in the life of the stars, and that remote events should embrace within themselves aeon upon aeon.

In your day you have learnt to calculate something of the magnitudes of time and space. But to grasp my theme in its true proportions, it is necessary to do more than calculate. It is necessary to brood upon these magnitudes, to draw out the mind toward them, to feel the littleness of your here and now, and of the moment of civilization which you call history. You cannot hope to image, as we do, such vast proportions as one in a thousand million, because your sense-organs, and therefore your perceptions, are too coarse-grained to discriminate so small a fraction of their total field. But you may at least, by mere contemplation, grasp more constantly and firmly the significance of your calculations.

Men of your day, when they look back into the history of their planet, remark not only the length of time but also the bewildering acceleration of life’s progress. Almost stationary in the earliest period of the earth’s career, in your moment it seems headlong. Mind in you, it is said, not merely stands higher than ever before in respect of percipience, knowledge, insight, delicacy of admiration, and sanity of will, but also it moves upward century by century ever more swiftly. What next? Surely, you think, there will come a time when there will be no further heights to conquer.

This view is mistaken. You underestimate even the foothills that stand in front of you, and never suspect that far above them, hidden by cloud, rise precipices and snow-fields. The mental and spiritual advances which, in your day, mind in the solar system has still to attempt, are overwhelmingly more complex, more precarious and dangerous, than those which have already been achieved. And though in certain humble respects you have attained full development, the loftier potencies of the spirit in you have not yet even begun to put forth buds.

Somehow, then, I must help you to feel not only the vastness of time and space, but also the vast diversity of mind’s possible modes. But this I can only hint to you, since so much lies wholly beyond the range of your imagination.

Historians living in your day need grapple only with one moment of the flux of time. But I have to present in one book the essence not of centuries but of aeons. Clearly we cannot walk at leisure through such a tract, in which a million terrestrial years are but as a year is to your historians. We must fly. We must travel as you do in your aeroplanes, observing only the broad features of the continent. But since the flier sees nothing of the minute inhabitants below him, and since it is they who make history, we must also punctuate our flight with many descents, skimming as it were over the house-tops, and even alighting at critical points to speak face to face with individuals. And as the plane’s journey must begin with a slow ascent from the intricate pedestrian view to wider horizons, so we must begin with a somewhat close inspection of that little period which includes the culmination and collapse of your own primitive civilization.

1. The European War and After

Observe now your own epoch of history as it appears to the Last Men.

Long before the human spirit awoke to clear cognizance of the world and itself, it sometimes stirred in its sleep, opened bewildered eyes, and slept again. One of these moments of precocious experience embraces the whole struggle of the First Men from savagery toward civilization. Within that moment, you stand almost in the very instant when the species attains its zenith. Scarcely at all beyond your own day is this early culture to be seen progressing, and already in your time the mentality of the race shows signs of decline.

The first, and some would say the greatest, achievement of your own ‘Western’ culture was the conceiving of two ideals of conduct, both essential to the spirit’s well-being. Socrates, delighting in the truth for its own sake and not merely for practical ends, glorified unbiased thinking, honesty of mind and speech. Jesus, delighting in the actual human persons around him, and in that flavour of divinity which, for him, pervaded the world, stood for unselfish love of neighbours and of God. Socrates woke to the ideal of dispassionate intelligence, Jesus to the ideal of passionate yet self-oblivious worship. Socrates urged intellectual integrity, Jesus integrity of will. Each, of course, though starting with a different emphasis, involved the other.

Unfortunately both these ideals demanded of the human brain a degree of vitality and coherence of which the nervous system of the First Men was never really capable. For many centuries these twin stars enticed the more precociously human of human animals, in vain. And the failure to put these ideals in practice helped to engender in the race a cynical lassitude which was one cause of its decay.

There were other causes. The peoples from whom sprang Socrates and Jesus were also among the first to conceive admiration for Fate. In Greek tragic art and Hebrew worship of divine law, as also in the Indian resignation, man experienced, at first very obscurely, that vision of an alien and supernal beauty, which was to exalt and perplex him again and again throughout his whole career. The conflict between this worship and the intransigent loyalty to Life, embattled against Death, proved insoluble. And though few individuals were ever clearly conscious of the issue, the first human species was again and again unwittingly hampered in its spiritual development by this supreme perplexity.

While man was being whipped and enticed by these precocious experiences, the actual social constitution of his world kept changing so rapidly through increased mastery over physical energy, that his primitive nature could no longer cope with the complexity of his environment. Animals that were fashioned for hunting and fighting in the wild were suddenly called upon to be citizens, and moreover citizens of a world-community. At the same time they found themselves possessed of certain very dangerous powers which their petty minds were not fit to use. Man struggled; but, as you shall hear, he broke under the strain.

The European War, called at the time the War to End War, was the first and least destructive of those world conflicts which display so tragically the incompetence of the First Men to control their own nature. At the outset a tangle of motives, some honourable and some disreputable, ignited a conflict for which both antagonists were all too well prepared, though neither seriously intended it. A real difference of temperament between Latin France and Nordic Germany combined with a superficial rivalry between Germany and England, and a number of stupidly brutal gestures on the part of the German Government and military command, to divide the world into two camps; yet in such a manner that it is impossible to find any difference of principle between them. During the struggle each party was convinced that it alone stood for civilization. But in fact both succumbed now and again to impulses of sheer brutality, and both achieved acts not merely of heroism, but of generosity unusual among the First Men. For conduct which to clearer minds seems merely sane, was in those days to be performed only by rare vision and self-mastery.

As the months of agony advanced, there was bred in the warring peoples a genuine and even passionate will for peace and a united world. Out of the conflict of the tribes arose, at least for a while, a spirit loftier than tribalism. But this fervour lacked as yet clear guidance, lacked even the courage of conviction. The peace which followed the European War is one of the most significant moments of ancient history; for it epitomizes both the dawning vision and the incurable blindness, both the impulse toward a higher loyalty and the compulsive tribalism of a race which was, after all, but superficially human.

2. The Anglo-French War

One brief but tragic incident, which occurred within a century after the European War, may be said to have sealed the fate of the First Men. During this century the will for peace and sanity was already becoming a serious factor in history. Save for a number of most untoward accidents, to be recorded in due course, the party of peace might have dominated Europe during its most dangerous period; and, through Europe, the world. With either a little less bad luck or a fraction more of vision and self-control at this critical time, there might never have occurred that aeon of darkness, in which the First Men were presently to be submerged. For had victory been gained before the general level of mentality had seriously begun to decline, the attainment of the world state might have been regarded, not as an end, but as the first step toward true civilization. But this was not to be.

After the European War, the defeated nation, formerly no less militaristic than the others, now became the most pacific, and a stronghold of enlightenment. Almost everywhere, indeed, there had occurred a profound change of heart, but chiefly in Germany. The victors on the other hand, in spite of their real craving to be human and generous, and to found a new world, were led partly by their own timidity, partly by their governors’ blind diplomacy, into all the vices against which they believed themselves to have been crusading. After a brief period in which they desperately affected amity for one another they began to indulge once more in physical conflicts. Of these conflicts, two must be observed.

The first outbreak, and the less disastrous for Europe, was a short and grotesque struggle between France and Italy. Since the fall of ancient Rome, the Italians had excelled more in art and literature than in martial achievement. But the heroic liberation of Italy in the nineteenth Christian century had made Italians peculiarly sensitive to national prestige; and since among Western peoples national vigour was measured in terms of military glory, the Italians were fired, by their success against a rickety foreign domination, to vindicate themselves more thoroughly against the charge of mediocrity in warfare. After the European War, however, Italy passed through a phase of social disorder and self-distrust. Subsequently a flamboyant but sincere national party gained control of the State, and afforded the Italians a new self-respect, based on reform of the social services, and on militaristic policy. Trains became punctual, streets clean, morals puritanical. Aviation records were won for Italy. The young, dressed up and taught to play at soldiers with real fire-arms, were persuaded to regard themselves as saviours of the nation, encouraged to shed blood, and used to enforce the will of the Government. The whole movement was engineered chiefly by a man whose genius in action combined with his rhetoric and crudity of thought to make him a very successful dictator. Almost miraculously he drilled the Italian nation into efficiency. At the same time, with great emotional effect and incredible lack of humour, he trumpeted Italy’s self-importance, and her will to ‘expand’. And since Italians were slow to learn the necessity of restricting their population, ‘expansion’ was a real need.

Thus it came about that Italy, hungry for French territory in Africa, jealous of French leadership of the Latin races, indignant at the protection afforded to Italian ‘traitors’ in France, became increasingly prone to quarrel with the most assertive of her late allies. It was a frontier incident, a fancied ‘insult to the Italian flag’, which at last caused an unauthorized raid upon French territory by a small party of Italian militia. The raiders were captured, but French blood was shed. The consequent demand for apology and reparation was calm, but subtly offensive to Italian dignity. Italian patriots worked themselves into short-sighted fury. The Dictator, far from daring to apologize, was forced to require the release of the captive militiamen, and finally to declare war. After a single sharp engagement the relentless armies of France pressed into North Italy. Resistance, at first heroic, soon became chaotic. In consternation the Italians woke from their dream of military glory. The populace turned against the Dictator whom they themselves had forced to declare war. In a theatrical but gallant attempt to dominate the Roman mob, he failed, and was killed. The new government made a hasty peace, ceding to France a frontier territory which she had already annexed for ‘security’.

Thenceforth Italians were less concerned to outshine the glory of Gari

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...