- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

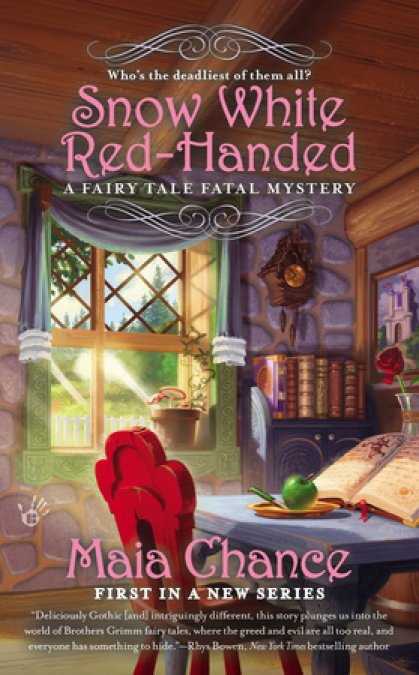

Synopsis

Miss Ophelia Flax is a Victorian actress who knows all about making quick changes and even quicker exits. But to solve a fairy-tale crime in the haunted Black Forest, she’ll need more than a bit of charm…

1867: After being fired from her latest variety hall engagement, Ophelia acts her way into a lady’s maid position for a crass American millionaire. But when her new job whisks her off to a foreboding castle straight out of a Grimm tale, she begins to wonder if her fast-talking ways might have been too hasty. The vast grounds contain the suspected remains of Snow White’s cottage, along with a disturbing dwarf skeleton. And when her millionaire boss turns up dead—poisoned by an apple—the fantastic setting turns into a once upon a crime scene.

To keep from rising to the top of the suspect list, Ophelia fights through a bramble of elegant lies, sinister folklore, and priceless treasure, with only a dashing but mysterious scholar as her ally. And as the clock ticks towards midnight, she’ll have to break a cunning killer’s spell before her own time runs out…

Release date: November 4, 2014

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Snow White Red-Handed

Maia Chance

She drew the slipper from her cloak. Her eyes, adjusting to the thin moonlight, picked out the faintest of shapes on a path between two rows of trees. Could they be . . . footprints?

1

SS Leviathan

Somewhere on the Atlantic Ocean

August 1867

Miss Ophelia Flax was neither a professional confidence trickster nor a lady’s maid, but she’d played both on the stage. In desperate circumstances like these, that would have to do.

“Who told you that our maid Marie gave notice?” Mrs. Coop said. Her diamond earrings wobbled.

Miss Amaryllis, sitting beside Mrs. Coop on the sofa, sniffed and added, “Uppity French tart.”

If ever there were two wicked stepsisters, here they were, taking tea in the SS Leviathan’s stuffy first-class stateroom number eighteen: thick-waisted, brassy-haired Mrs. Coop, clutching at her fading bloom in a deshabille gown of pink ribbons and Brussels lace, and her much younger sister Miss Amaryllis, a bony damsel of twenty or so with complexion spots, slumped shoulders, and a green silk gown that resembled a lampshade. They looked up at Ophelia, expectant and hostile.

Ophelia stood before them, tall and plain in the gray woolen traveling dress, black gloves, and prim buttoned boots she’d borrowed—stolen was such a rotten word—from the costume trunks of Howard DeLuxe’s Varieties in the ship’s hold.

“Your maid’s abandonment of her post,” Ophelia said, “came to my attention during my midday promenade on the first-class deck.”

She needn’t mention that her own cramped berth was in the bowels of third class, where it stank of sour cabbage and you felt the ship’s engines vibrating in your teeth.

“Embarrassing scene.” Mrs. Coop pitched herself forward to reach for a cream puff. “The way Marie threw her apron at me! She always did behave as though she were my—my superior.”

“It wasn’t your fault, ma’am,” Ophelia said. “French maids are notoriously fickle. They’re not the best for service, I’m afraid.”

“But everyone in New York’s got one. They’re simply mad for them.”

“It is my understanding, ma’am, that while a certain . . . class of society cling to the outdated notion that a French lady’s maid is the height of elegance, the Van Der Snoots and De Schmeers and”—Ophelia scanned the stateroom’s luxurious furnishings—“St. Armoire ladies have of late discovered that a Yankee lady’s maid is best.”

“Yankee?” Mrs. Coop’s bitten cream puff hovered in midair. Yellowish filling oozed from the sides.

“Yes, ma’am. Yankee girls are honest, hardworking, modest, and loyal.”

Miss Amaryllis slitted her eyes. “I suppose you’re a Yankee girl?”

“Indeed I am. Born and bred on a farmstead in New Hampshire, miss.”

That was true. She’d leave out the bits about the textile mill and the traveling circus. They didn’t have the same wholesome ring.

“I’ll find a new maid when we reach Germany,” Mrs. Coop said. “I’ve made up my mind. Why, if I had known Marie would quit in the midst of my honeymoon voyage, I’d have left her on the dock in Manhattan!”

“Another virtue of Yankee girls,” Ophelia said, “is their ability to arrange coiffures, make cosmetic preparations, and, if needed—although I’m certain ma’am has no need—apply powders and tints with a hand as subtle as nature herself.”

A lie, of course. But Ophelia was an actress—or she had been up until four hours ago, when Howard DeLuxe had given Prue the boot and Ophelia had been obliged to quit—and putting on greasepaint was one thing she knew how to do well.

“Yankee girls use face paint?” Mrs. Coop said. “Why, you said it yourself. They’re as plain as potatoes.”

“But they learned from their grandmothers, ma’am, the arts of medicinal plants. My own gran taught me to whip up an elderflower tincture that returns the skin to snowy youth—”

Another fib. But Mrs. Coop’s eyes glimmered with interest.

“—and a Pomade Victoria of beeswax and almond oil that makes the hair shine like gold, a salve of Balsam Peru that makes complexion spots vanish.” Ophelia leaned forward. “I could not help noticing Miss Amaryllis’s unfortunate condition.”

“Why, the cheek!” Mrs. Coop’s bosom heaved.

Miss Amaryllis glared up at Ophelia and bit into a biscuit with a snap.

“And,” Ophelia said, “a pleasant-tasting tonic of vinegar that slims a lady’s waist without effort.”

Mrs. Coop’s half-eaten cream puff plopped onto her plate.

Ophelia had hooked her halibut.

“Here,” Ophelia said, drawing two sealed envelopes from her pocket, “are my letters of reference. I, and my young acquaintance, Miss Prudence Bright, were traveling to England to work in the employ of Lady Cheshingham at Greyson Hall in Shropshire.”

Lady Cheshingham was, in truth, the lead character in the risqué comedy Lady Cheshingham’s Charge, which Howard DeLuxe’s Varieties had performed in May. The letters were forgeries Ophelia had penned an hour earlier.

Mrs. Coop fingered the envelopes. “Ah, yes, yes, Lady Cheshingham.”

“While already shipboard, I belatedly read a missive I’d received from Lord Cheshingham on the eve of our voyage, which informed me that the lady had passed away.”

“Good heavens.”

“Yes. A tragedy. She was so young.”

“I had heard so many wonderful things about her.”

“Miss Bright and I, then, are in want of employment.”

Want of employment didn’t really pin down the gravity of their circumstances. With the steamship barreling towards Southampton, Ophelia and Prue, with no jobs, only a few dollars, and no acquaintances in England, were well and truly up a stump.

“There are two of you?” Mrs. Coop sounded uncertain. “I—I must ask my husband. We are staying at our castle only until the winter.”

Castle? Hm. Surely a figure of speech.

“Of course,” Ophelia said, and made a show of tearing at the cambric handkerchief she’d plucked from her sleeve.

But she oughtn’t get too carried away in her role. Mr. DeLuxe had always complained that she, having once beguiled her audience, tended to careen towards the melodramatic.

She put the hankie away. “Have you, ma’am, tried Russian face powder?”

Mrs. Coop touched her thickly powdered cheek. “I’ve always used French.”

“Russian is the best, used first by the czarina Catherine. It’s got crushed pearls in it—pearls from the North Sea, which restore the complexion to a state of infancy. But don’t tell anyone. It’ll be our little secret.”

“Pearls for Mrs. Pearl Coop,” Miss Amaryllis said into her teacup. “How poetic.”

“It is easier, Amaryllis,” Mrs. Coop said through clenched teeth, “to catch flies with honey than with vinegar.”

“Whatever would I want with flies?”

“A figure of speech, dear. Perhaps it would be best if you married your own fly, rather than straggling along with Homer and me.”

“Homer a fly?” Miss Amaryllis smirked. “More of a frog, don’t you think?”

“If I may be so bold,” Ophelia interrupted, “it would be a privilege to attend to such lovely, refined ladies.”

Mrs. Coop blinked, and Miss Amaryllis leaned against the sofa arm and propped her chin sulkily on her hand.

Mrs. Coop sighed and picked up her cream puff. “It seems we’ve no choice in the matter. When can you start?”

Ophelia held in an exhalation of relief. “Immediately, ma’am,” she said.

* * *

“Well?” Prue flung herself face-up on her narrow berth. Her cheeks were blotchy and wet with tears.

Ophelia shut the cabin door. “We have jobs.”

“That’s splendiferous!”

“I am to be a lady’s maid—”

Prue’s face fell.

“—and you are to be a scullery maid.”

“Scullery maid?” Prue struggled to a seated position. Golden ringlets tumbled around her flushed face and her eyes of enamel blue. She was the closest thing to a china doll that a nineteen-year-old American girl could be. Until, that is, she opened her mouth to speak. “I ain’t cut out for a scullery maid, Ophelia. I’m clumsy, for starters, but more than that, I ain’t got the concentration to peel carrots all day.”

Ophelia wholeheartedly agreed. “You’ll manage,” she said. She stripped off the stolen gloves. “It’s only a bit of washing pots and scrubbing vegetables.”

“Why can’t I be a lady’s maid, too?”

“Mrs. Coop and Miss Amaryllis desired but one lady’s maid between them. We are lucky they agreed to take you on at all. Don’t look so weepy. It’s only for a few months, until we save up enough to buy passage back to America. Besides, we don’t have another plan.”

The plan had been to perform with Howard DeLuxe’s Varieties in its limited engagement at the Pegasus Theater on the Strand. “Limited engagement” meant for however long gin-soaked London gents would pack the seats to watch the troupe’s bawdy skits and musical numbers. “The Lusty Whalers of Nantucket” had top billing, alongside a bit about cowgirls and Indians, a romantic scene in which Ophelia played Pocahontas, and “Paul Revere’s Bride,” featuring a horse that galloped offstage with a scantily clad Puritan wench.

“We could go find my Ma,” Prue said. “Nat—you know, the feller who paints the scenery—told me this afternoon he heard she was in Europe.”

“We haven’t any notion where.” Ophelia sank onto the edge of her own berth. “Europe is enormous, not to mention expensive. And she could just as easily be in New York.”

“A scullery maid.” Prue’s tears were spouting again. “What’ll become of me? I ain’t got anyone. Ma never wanted me—”

“Now you know that isn’t true.” Ophelia handed over a hankie.

“If she’d hornswoggled a millionaire into marrying her when I was a baby, she would’ve left me then.”

“Nonsense.”

Prue noisily blew her nose.

Her mother, Miss Henrietta Bright, had been the star actress in Howard DeLuxe’s Varieties, and like so many actresses, she had supplemented her income with—to mince words—additional business endeavors. Last year, she’d run off with one of her admirers. Some said he was a Wall Street tycoon, others that he was a European blue blood. Either way, Prue’s mother had abandoned a flighty girl who possessed all the common sense of a tadpole. Ophelia had no living family of her own—a missing brother and a father she’d never met hardly counted—so she’d taken Prue under her wing.

Ophelia bent to unbutton the stolen boots; they were too small, and her toes felt numb. “You know I have a little money saved up, in the bank in New York—”

“For your farm! You’ve been scrimping for ages.”

“I have.” A vision of misty green fields, a white barn, and sweet-eyed dairy cows rose up in Ophelia’s mind’s eye. It was a vision that often lulled her to sleep, that got her through slushy November afternoons and exhausting double matinee performances. “When I buy my farm someday, well, you can come and live with me there.”

Prue wrinkled her nose. “Will I have to milk the cows?”

“Certainly not.”

“Snatch it, you’re just being nice. You’re always being too nice. Just because Mr. DeLuxe sent me packing don’t mean you should’ve quit.”

Ophelia said nothing as she yanked off the boots. But she knew exactly what became of pretty, silly, penniless girls who didn’t have a protector, and the idea of Prue alone on the streets of London didn’t bear thinking about.

“You could’ve been a lead actress someday, Ophelia. And now you’re just a maid.”

“Fiddlesticks. Acting has merely been a way to pay for my daily bread.”

“When you filled in as Cleopatra when Flossie broke her arm, you got a standing ovation and enough roses to fill three bathtubs. You were a stunner.”

“In a wig and greasepaint,” Ophelia said. “Gospel truth, it doesn’t concern me in the least that without Cleopatra kohl-lined eyes or Marie Antoinette rouged cheeks, I blend nicely into the backdrop. I’m five and twenty years of age, plenty old enough to have made peace with myself. I’m not saying I’m some mousy thing who gets stepped on—”

“Course not. You’re a beanstalk.”

“Not as tall as that, perhaps.” In truth, Ophelia was tall, and she had large feet, and no corset could mold her straight figure into a fashion plate’s hourglass. But her oval face, molasses-colored eyes, and light brown hair were presentable enough. “Anyway, since I’m an actress, a knack for blending in is an asset.” She wiggled her blissfully freed toes. “Now. If we’re ever to get back home in one piece, we ought to prepare ourselves for our new roles as maids.”

* * *

“Where in tarnation are they taking us?” Prue said three days later. She scrubbed at the grimy coach window with her fist. Their coach creaked and jostled up the mountainous road like a rheumatic mule. “Everything was all right until we got off at that bad railway station—”

“Baden-Baden,” Ophelia corrected from the opposite seat. “Baden means baths—it’s a thermal resort town.”

“That in your book?” Ophelia had had her nose stuck in some book she’d borrowed from Miss Amaryllis for the whole of their railway and boat journey between Southampton and Germany. It was called a Baedeker, Ophelia had told Prue. Whatever that meant. Prue hadn’t bothered to thumb through it. She considered herself a doing kind of person. Book learning gave her the jitters.

Besides, Ma had always cautioned that reading gave a lady a scrunched-up forehead and a panoramic derriere.

Baden-Baden, a German town nestled in plush hills, was called the Paris of the summer months. Leastways, that’s what the Baedeker said. All the cream of Europe’s crop, from Polish princes and British nobles to Italian opera stars and Russian novelists, gathered there to socialize, dance, take the waters, and gamble at the races or in the opulent gaming rooms.

But their coach had left Baden-Baden miles behind, and they were headed up into the mountains.

“I reckoned,” Prue said, “when we took that boat to Brussels, we were headed to civilization. But this!” She scowled out the window. Mountains reared up into the chambray-colored sky. “This looks worse than Maine.”

“We’re in the Black Forest, Prue. Haven’t you heard of it?”

“Never.”

“Your mother didn’t read you those fairy stories by the Grimm Brothers?”

“Read me stories?” Prue bit into one of the strawberry jelly sweets she’d spent her last penny on, back at the railway station. “Not her. But I sure know how to tell real diamonds from paste, and if a gentleman’s got a walloping bank account or is just trying to dupe a lady.” She chewed hard. The topic of Ma made her feel sore somewhere under her ribs. “Looks like the first-class carriage is getting away from us.”

“We are servants now,” Ophelia said. Her voice was gentle. “We can’t expect to ride with the family.”

“Can’t expect a decent coach, neither.”

“I allow, this coach isn’t the most comfortable—”

“It’s a rickety old rattletrap.” Prue eyed the black wood fittings around the window: carved thorny vines. “Or maybe a hearse.”

“We are fortunate to have found employment.”

“Well, don’t that beat all!” Prue exclaimed. “Look at that castle.”

“Where?”

“Up there.”

Ophelia followed Prue’s pointed finger. “That,” she murmured, “beats all indeed.”

High on a jutting stone outcrop, framed by pine trees, was a castle. It was built of pale stone, with turrets of various sizes, battlements, walls, parapets, and balconies. It glowed like an enchanted wedding cake in the afternoon sun, and hazy mountains stretched endlessly behind it like a painted theater backdrop.

“Ain’t got those in Maine.” Prue popped another strawberry jelly in her mouth.

“I think,” Ophelia said, “that’s where we’re going to live.”

2

Two weeks later

“Snow White’s little house,” Professor Winkler said in his thick German accent, “the house, you understand, in the wood wherein she lived with her seven dwarves, has been, according to the telegram, found.” He chuckled, holding tight to a hand strap as the carriage bumped up the mountain road. “Such beliefs, of course, are merely fancies of the peasantry. I cannot think how this American millionaire’s wife got hold of such a notion, particularly since she has been in Germany only a few weeks.”

“Curious indeed,” Gabriel Augustus Penrose said. “And I do agree with you, it goes without saying that superstitious stories are the product of debased minds and, I suspect, poor nutrition as well.” He tried to stretch his long legs, which were stiff from that morning’s fifty-mile railway journey from Heidelberg to Baden-Baden. “We are fortunate that the philological work that began with Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm laid the groundwork for a more enlightened understanding of fairy tales.”

“But the folk are wily, Professor Penrose, and ready to defend their backwards beliefs to the death. Why, once, in a dark, kleine hamlet in the Brigach River valley, I encountered an old crone who swore that she was the great-great-granddaughter of Gretel.”

“Of ‘Hansel und Gretel’?” Gabriel raised an eyebrow as he straightened his spectacles, a bemused, condescending look he’d perfected years ago.

“The same. How I did laugh at the miserable thing. By the sorry appearance of her teeth, I judged she had eaten a fair share of candy windows and cake roofs herself. Now, where is this Schloss Grunewald?” Winkler hunched his aged, oxlike frame to better see out the carriage window. “Mr. Coop’s telegram indicated that it was five miles from the Baden-Baden station. Ah. There. I see the towers through the trees. One of those piles the romantics renovated to appear more picturesque.”

Gabriel glimpsed the castle, too, floating like a mirage over a half-timbered village in a valley. “I was told,” he said, “that the schloss retains portions that are ancient, but the greater part was rebuilt in the twenties by the grandfather of the former owner—a certain Count Grunewald—as a summer retreat.” He paused to admire the effect of the castle’s creamy stones surrounded by emerald mountains. “So, it would seem that it isn’t only the peasants who indulge in romantic notions.”

Winkler gave him a sharp look. “It is not the same, is it?”

“Mmm,” Gabriel said, and pretended to be deep in a study of the passing forest.

Hang it. That had been a slipup.

Gabriel had built his academic career upon a rather snobbish outlook on the origins and significance of folklore. As professor of philology at St. Remigius’s College, Oxford, he painstakingly researched archaic texts to expose the deluded—but nonetheless fascinating—imaginations of a pagan folk that still lingered in remote pockets of modern Europe. Fairy tales and myths were nothing but drivel, he and his colleagues insisted.

He was obliged to keep it hidden that he believed quite the opposite. That he had believed in the inexplicable ever since that strange, magical dawn in the Crimea almost thirteen years ago.

“Thank you,” he said to Winkler, “for bringing me along, by the way. I’m interested to see how you set these superstitious people to rights.”

“I am called upon to do it more than I care to admit. The benefit is that the remote hamlets, where these summons usually bring me, have some of the best food and drink in all of Germany. Ach, the bratwurst I dined upon when some fools thought they had found golden straw sealed up in an ancient silo. I must have eaten two hogs’ worth! With a kraut to accompany it that—oh!—it was worth all the annoyance.” He smacked his lips.

“It was fortuitous that I encountered you at the university last night,” Gabriel said. “I usually conduct my evening studies at my rented rooms in the Klingenteichstrasse. I’d only gone in to the university because I’d forgotten a book.” Gabriel was spending the summer as a visiting scholar at Heidelberg University in order to examine a crumbling fifteenth-century manuscript.

“I am pleased to have you along.”

Gabriel eyed the black bag resembling a doctor’s bag on the seat beside Winkler. “What sort of things do you do when you’re called upon to investigate so-called fairy tale evidence?”

“It is all strictly scientific, very precise. While I, like you, am a philologist, as a young man, I studied chemistry. In that kit there”—Winkler gestured with his chins towards the bag—“you shall find an array of testing equipment.”

“Testing? For—?”

Winkler chuckled again. “Gold, my dear professor. The peasants always believe they have discovered dwarf’s gold.”

* * *

Winkler and Gabriel stepped down from their carriage into Schloss Grunewald’s forecourt.

“You the college men?” A middle-aged gentleman gestured towards them with a half-eaten apple.

“Professor Penrose,” Gabriel said, extending his deerskin-gloved hand. “And this is my esteemed colleague, Professor Winkler.”

“Coop. Homer T. Coop.” Coop’s handshake was as gruff as his American accent. He had a bristling mustache and side-whiskers, and his head was shrubbed with coppery hair streaked with gray. He was barrel-chested and wearing a well-tailored checked suit and a porkpie hat. His hands were not gloved, and they looked more suited to a railway gang laborer than a railway millionaire. “I want you to know straight off,” Coop said, “that I don’t have time for this tomfoolery. I telegraphed you on account of my wife, Pearl.”

“So you mentioned,” Winkler said, “in your telegram.”

“Her head’s rotted with this storybook nonsense, as if she were a little miss of six. One of the servants told her about the famous fairy tale professor in Heidelberg, and she wouldn’t stop buzzing in my ear like a dangnabbed mosquito about it until I agreed to send a telegram.” He gnawed his apple. “Never went to college myself. Guess I’m a good example of how you don’t need it.” He snorted. “I started off on Wall Street, you know. Worked for a Harvard man. He never did manage to get his snotty nose down low enough to sniff out a bad deal. Went bankrupt in forty-nine. That’s when I cleared out.”

“Shall we have a look at the find?” Gabriel said.

“It’s now or never,” Coop said. “I mean to raze the house once you’ve looked it over.” He suddenly bellowed, “Smith!” He threw the apple core onto the flagstones. “Smith,” he said to Gabriel and Winkler, “is my right hand. I don’t cotton to manservants and the like, such as you European fellers have. But for business matters, I’ve got Smith.”

“Mr. Coop?” someone said.

Gabriel and Winkler turned. It was a brilliant summer morning, and sunny where they stood, but half of the forecourt was still in shadow. So when Gabriel followed the meek voice, his sun-dazzled eyes convinced him that one of the crouching stone gargoyles that flanked the steps leading up to the castle doors had come to life and was skulking towards them.

Gabriel’s breath caught. There it was, that feeling he’d had a handful of times before. A sense of the bottom quite falling out of reality, and wonderment and magic gusting in.

He blinked. His eyes adjusted to the shadows, and he saw, with combined relief and dismay, that it was only a remarkably short gentleman and that the gargoyles by the stair hadn’t moved an inch.

“This here’s my secretary,” Coop said, “Mr. George Smith.”

Smith shook their hands. He had a face like an intelligent pug dog, and graying hair parted and combed like a schoolboy’s. He wore a neat suit of flannels and a bowler hat.

“Come on,” Coop said to Smith. “Let’s take these college boys out to the woods.”

* * *

They left the castle behind and tramped through rugged, sun-dappled hills for twenty minutes.

“Right through here,” Smith called over his shoulder. He led the way up through a dry gully, Gabriel close behind, followed by Winkler and Coop.

All of a sudden, a figure emerged on the path ahead. A sturdy woman, in a dust-colored walking costume, leather belt, and broad-brimmed straw hat. She was all alone. She strode towards them, a leather satchel swinging from her shoulder. She had a large, bland face, a nose like a drawer knob, and pale, nearly invisible eyebrows over lashless gray eyes. Her cheeks were flushed with exertion or, perhaps, sunburn.

The men paused to allow her to pass.

“Fancy meeting anyone out here in this wilderness,” she called.

British. The world was simply crawling with British tourists. You could be shipwrecked at the farthest reaches of the globe, wearing mere tatters and chomping coconuts, and look up to see one of the queen’s hale subjects striding out of the brush in a safari jacket and a pith helmet.

“Good morning,” Gabriel said. He lifted his hat. “Pleasant day for a tramp, isn’t it?”

“Oh yes,” she said in a hearty voice. “Absolutely ripping. Watch out for the flies,” she added over her shoulder. “Horrid little mites. Swarmed like cannibals and made a feast of my apple.”

She loped out of sight around a turn in the gully.

“Got to put up some private property signs, Smith,” Mr. Coop said.

They continued on their way up the path.

Presently, the gully opened out onto a forest glade filled with wild blueberry bushes and enormous trees.

The four men paused to mop their brows with handkerchiefs.

The glade had an enchanted feeling to it. Insects hummed, the air was spicy-sweet with pinesap and wildflowers, and sunlight mottled the mossy ground.

“The castle woodsman, Herz,” Smith said, “will cut these three trees just here”—he gestured with a small gloved hand—“and in preparation yesterday, he was clearing out the undergrowth. To get at the trunks of the trees, see.”

“Forgive my impertinence,” Gabriel said, “but why would one cut these trees? They must be at least four hundred years old.” The pine trees, as big around as barrels, rose cathedral-like into the azure sky. Aloft, their boughs bounced in the breeze.

“Clear the view,” Coop said. He propped his thick, booted leg on a boulder, pulled another green apple from his jacket pocket, and bit it. “I was looking out my st

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...