- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

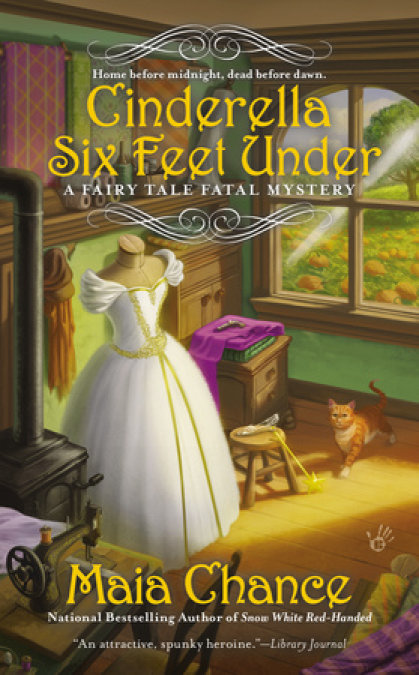

This Cinderella goes from ashes to ashes in the new Victorian-era Fairy Tale Fatal Mystery by the author of Snow White Red-Handed . . .

Variety hall actress Ophelia Flax’s plan to reunite her friend Prue with her estranged—and allegedly wealthy—mother, Henrietta, is met with a grim surprise. Not only is the marquise’s Paris mansion a mouse-infested ruin, but Henrietta has inexplicably vanished, leaving behind an evasive husband, two sinister stepsisters, and a bullet-riddled corpse in the pumpkin patch decked out in a ball gown and one glass slipper—a corpse that also happens to be a dead ringer for Prue.

Strangely, no one at 15 rue Garenne seems concerned about who plugged this luckless Cinderella or why, so the investigation is left to Ophelia and Prue. It takes them through the labyrinthine maze of the Paris Opera, down the trail of a legendary fairy tale relic, into the confidence of a wily prince charmless, and makes them vulnerable to the secrets of a mysterious couturière with designs of her own on Prue’s ever-twisting family history.

Release date: September 1, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cinderella Six Feet Under

Maia Chance

1

November, 1867

Oxford, England

The murdered girl, grainy in black-and-gray newsprint, stared up at him. Her eyes were mournful and blank.

Gabriel placed the chipped Blue Willow teacup beside the picture. His hand shook, and tea sloshed onto the newspaper. Ink bled.

Gabriel Augustus Penrose, although a bespectacled professor, hadn’t—not yet, at least—developed round shoulders or a nearsighted scowl. Although, such shoulders and such a scowl would have suited the oaken desk, swaybacked sofa, towers of books, and swirling dust motes in his study at St. Remigius’s College, Oxford. And at four-and-thirty years of age, Gabriel was certainly not given to fits of trembling.

But this.

He tore his eyes from the girl’s. Was it today’s newspaper? He glanced at the upper margin—yes. Perhaps there was still time.

Time for . . . what?

He didn’t customarily peruse the papers during his four o’clock cup of tea, but a student had come to see him and he’d happened to leave The Times behind. The morgue drawing was on the fourth page, tucked between a report about a Piccadilly thief and an advertisement for stereoscopic slides. A familiar, lovely, and—according to the report—dead face.

SENSATIONAL MURDER IN PARIS: In the Marais district, a young woman was found dead as the result of two gunshot wounds in the garden of the mansion of the Marquis de la Roque-Fabliau, 15 Rue Garenne. She is thought to be the daughter of American actress Henrietta Bright, who wed the marquis in January. The family solicitor said that it is not known how the tragic affair arose, and that the family was unaware of the daughter’s presence in Paris. The commissaire de police of that quarter has undertaken an assiduous search for her murderer.

Gabriel removed his spectacles, leaned forward on his knees, and laid his forehead in his palm. The murdered girl, Miss Prudence Bright, was a mere acquaintance. Perhaps the same might be said of Miss Ophelia Flax, the young American actress who had been traveling with Miss Bright when he’d encountered them in the Black Forest several weeks ago.

Mere acquaintance. The term could not account for the ripping sensation in his lungs.

Gabriel replaced his spectacles, stood, and strode to the jumbled bookcase behind his desk. He drew an antique volume from the shelf: Histoires ou contes du temps passé—Stories or Fairy Tales from Past Times—by Charles Perrault. He flipped through the pages, making certain a loose sheet of paper was still wedged inside.

He stuffed the volume in his leather satchel, along with his memorandum book, yanked on his tweed jacket, clamped on his hat, and made for the door.

Two Days Earlier

Paris

The mansion’s door-knocker was shaped like a snarling mouse’s head. Its bared teeth glinted in the gloom and raindrops dribbled off its nose. It ought to have been enough of a warning. But Miss Ophelia Flax was in no position to skedaddle. Yes, her nerves twanged like an out of tune banjo. But she’d come too far, she had too little money, and rainwater was making inroads into her left boot. She would stick to her guns.

“Ready?” she asked Prue, the nineteen-year-old girl dripping next to her like an unwrung mop.

“Can’t believe Ma would take up residence in a pit like this,” Prue said. Her tone was all bluster, but her china-doll’s face was taut beneath her bonnet, and her yellow curls drooped. “You sure you got the address right?”

“Certain.” The inked address had long since run, and the paper was as soggy as bread pudding by now. However, Ophelia had committed the address—15 Rue Garenne—to memory, and she’d studied the Baedeker’s Paris map in the railway car all the way from Germany, where she and Prue had lately been employed as maids in the household of an American millionaire. “It’s hardly a pit, either,” Ophelia said. “More like a palace. It’s past its prime, that’s all.” The mansion’s stones, true, were streaked with soot, and the neighborhood was shabby. But Henrietta’s mansion would dwarf every building in Littleton, New Hampshire, where Ophelia had been born and raised. It was grander than most buildings in New York City, too.

“I reckon Ma, of all people, wouldn’t marry a poor feller.”

“Likely not.”

“But what if she ain’t here? What if she went back to New York?”

“She’ll be here. And she’ll be ever so pleased to see you. It’s been how long? Near a twelvemonth since she . . .” Ophelia’s voice trailed off. Keeping up the chipper song and dance was a chore.

“This is cork-brained,” Prue said.

“We’ve come all this way, and we’re not turning back now.” Ophelia didn’t mention that she had just enough maid’s wages saved up for one—and only one—railway ticket to Cherbourg and one passage back to New York.

Prue’s mother, Henrietta Bright, had been the star actress of Howard DeLuxe’s Varieties back in Manhattan, up until she’d figured out that walking down the aisle with a French marquis was a sight easier than treading the boards. She had abandoned Prue, since ambitious brides have scant use for blossoming daughters.

But Prue and Ophelia had recently discovered Henrietta’s whereabouts, so Ophelia fully intended to put her Continental misadventures behind her, just as soon as she installed Prue in the arms of her long-lost mother.

Before Ophelia could lose her nerve, she hefted the mouse-head door-knocker and let it crash.

Prue eyed Ophelia’s disguise. “Think she’ll buy that getup?”

“Once we’re safe inside, I’ll take it off.”

The door squeaked open.

A grizzle-headed gent loomed. His spine was shaped like a question mark and flesh-colored bumps studded his eyelids. A steward, judging by his drab togs and stately wattle.

“Good evening,” Ophelia said in her best matron’s warble. “I wish to speak to Madame la Marquise de la Roque-Fabliau.” What a mouthful. Like sucking on marbles.

“Regrettably, that will not be possible,” the steward said.

He spoke English. Lucky.

The steward’s gaze drifted southward.

Ophelia was five-and-twenty years of age, tall, and beanstalk straight as far as figures went. However, at present she appeared to be a pillowy-hipped, deep-bosomed dame in a black bombazine gown and woolen cloak. A steel-gray wig and black taffeta bonnet concealed her light brown hair, and cosmetics crinkled her oval face. All for the sake of practicality. Flibbertigibbets like Prue required chaperones when traveling, so Ophelia had dug into her theatrical case and transformed herself into the sort of daunting chaperone that made even the most shameless lotharios turn tail and pike off.

“Now see here!” Ophelia said. “We shan’t be turned out into the night like beggars. My charge and I have traveled hundreds of miles in order to visit the marquise, and we mean to see her. This young lady is her daughter.”

The steward took in Prue’s muddy skirts, her cheap cloak and crunched straw bonnet, the two large carpetbags slumped at their feet. He didn’t budge.

Stuffed shirt.

“Baldewyn,” a woman’s voice called behind him. “Baldewyn, qui est là?” There was a tick-tick of heels, and a dark young lady appeared. She was perhaps twenty years of age, with a pointed snout of a face like a mongoose and beady little animal eyes to match.

“Pardonnez-moi, Mademoiselle Eglantine,” Baldewyn said, “this young lady—an American, clearly—claims to be a kinswoman of the marquise.”

“Kinswoman?” Eglantine said. “How do you mean, kinswoman? Of my belle-mère? Oh. Well. She is . . . absent.”

Ophelia had picked up enough French from a fortune-teller during her stint in P. Q. Putnam’s Traveling Circus a few years back to know what belle-mère meant: stepmother.

“No matter,” Ophelia said. “Mademoiselle, may I present to you your stepsister, Miss Prudence Deliverance Bright?”

“I assure you,” Eglantine said, “I have but one sister, and she is inside. I do not know who you are, or what sort of little amusement you are playing at, but I have guests to attend to. Now, s’il vous plaît, go away!” She spun around and disappeared, the tick-tick of her heels receding.

Baldewyn’s dour mouth twitched upwards. Then he slammed the door in their noses.

“Well, I never!” Ophelia huffed. “They didn’t even ask for proof!”

“I told you Ma don’t want me.”

“For the thousandth time, humbug.” Ophelia hoisted her carpetbag and trotted down the steps, into the rain. “She doesn’t even know you’re on the European continent, let alone on her doorstep. That Miss Eglantine—”

“Fancies she’s the Queen of Sheba!” Prue came down the steps behind her, hauling her own bag.

“—said your mother is absent. So all we must do is wait. The question is, where?” They stood on the sidewalk and looked up and down the street lined with monumental old buildings and shivering black trees. A carriage splashed by, its driver bent into the slanting rain. “We can’t stay out of doors. May as well be standing under Niagara Falls. I’m afraid my greasepaint’s starting to run, and this padding is like a big sponge.” Ophelia shoved her soaked pillow-bosom into line. “Come on. Surely we’ll find someplace to huddle for an hour or so. Your sister—”

“Don’t call her that!”

“Very well, Miss Eglantine said they’ve got guests. So I figure your mother will be home soon.”

The mansion’s foundation stones went right to the pavement. No front garden. But farther along they found a carriageway arch. Its huge iron gates stood ajar.

“Now see?” Ophelia said. “Nice and dry under there.”

“Awful dark.”

“Not . . . terribly.”

More hoof-clopping. Was it—Ophelia squinted—was it the same carriage that had passed by only a minute ago? Yes. It was. The same bent driver, the same horses. And—

Her heart went lickety-split.

—and a pale smudge of a face peering out the window. Right at her.

Then it had gone.

* * *

On the other side of the carriageway arch lay a big, dark courtyard. Wings of Henrietta’s mansion bordered it on two sides. The third side was an ivy-covered carriage house and stables, where an upstairs window glowed with light. The fourth side was a high stone wall. The garden seemed neglected. Shrubs were shaggy, weeds tangled the flower beds, and the air stank of decay.

“Look,” Prue said, pointing. “A party.”

Light shone from tall windows. Figures moved about inside and piano music tinkled.

“Let’s have a look.” Ophelia abandoned her carpetbag under the arch and set off down a path. Wet twigs and leaves dragged at her skirts.

“You mean spy on them?”

“Miss Eglantine didn’t seem the most honest little fish.”

“And that Baldy-win feller was a troll.”

“So maybe your ma is really in there, after all.”

Up close to the high windows, it was like peeping into a jewel box: cream paneled walls with gold-leaf flowers and swags, and enough mirrors and crystal chandeliers to make your eyes sting. A handful of richly dressed ladies and gentlemen loitered about. A plump woman in a gray bun—a servant—stood against a wall. A frail young lady in owlish spectacles crashed away at the piano.

“There’s Eggy,” Prue said. “Maybe that’s the sister she mentioned.” A third young lady in a lavish green tent of a gown sat next to Eglantine.

“Same dark hair,” Ophelia said.

“Same mean little eyes.”

“A good deal taller, however, and somewhat . . . wider.”

“Spit it out. She looks like a prizefighter in a wig.”

“Prue! That might be your own sister you’re going on about.”

“Stepsister. Look—they’re having words, I reckon. Eggy don’t seem too pleased.”

The young ladies’ heads were bent close together, and they appeared to be bickering. The larger lady in green had her eyes stuck on something across the room.

Ah. A gentleman. Fair-haired, flushed, and strapping, crammed into a white evening jacket with medals and ribbons, and epaulets on the shoulders. He conversed with a burly fellow in black evening clothes who had a lion’s mane of dark gold hair flowing to his shoulders.

“Ladies quarreling about a fellow,” Ophelia said. “How very tiresome.”

“Some fellers are worth talking of.”

“If you’re hinting that I care to discuss any gentleman, least of all Professor Penrose, then—well, I do not, I sincerely do not feel a whit of sentiment for that man.”

“Oh, sure,” Prue said.

Ophelia longed for things, certainly. But not for him. She longed for a home. She longed, with that gritted-molars sort of longing, to be snug in a third-class berth in the guts of a steamship barging towards America. She’d throw over acting, head up north to New Hampshire or Vermont, get work on a farmstead. Merciful heavens! She knew how to scour pots, tend goats, hoe beans, darn socks, weave rush chair seats, and cure a rash with apple cider vinegar. So why was she gallivanting across Europe, penniless, half starved, and shivering, in this preposterous disguise?

“Duck!” Prue whispered.

There was a clatter above, voices coming closer; someone pushed a window open.

Ophelia and Prue stumbled off to the side until they were safely in shadow once more. They’d come to the second wing of the mansion. All of the windows were black except for two on the main floor.

“Let’s look,” Ophelia whispered. “Could be your ma.”

They picked their way towards the windows, into what seemed to be a marshy vegetable patch.

Ophelia stepped around some sort of half-rotten squash, and wedged the toe of her boot between two building stones. She gripped the sill to pull herself up, and her waterlogged rump padding threatened to pull her backwards. She squinted through the glass. “Most peculiar,” she whispered. “Looks like some sort of workshop. Tables heaped with knickknacks.”

“A tinker’s shop?” Prue clambered up. “Oh. Look at all them gears and cogs and things.”

“Why would there be a tinker’s shop in this grand house? Your ma married a nobleman. Yet it’s on the main floor of the house, not down where the servants’ workplaces must be.” A fire burned in a carved fireplace and piles of metal things glimmered.

“Crackers,” Prue whispered. “Someone’s in there.”

Sure enough, a round, bald man hunched over a table. One of his hands held a cube-shaped box. The other twisted a screwdriver. Ophelia couldn’t see his face because he wore brass jeweler’s goggles.

“What in tarnation is he doing?” Prue spoke too emphatically, and her bonnet brim hit the windowpane.

The man glanced up. The lenses of his goggles shone.

Holy Moses. He looked like something that had crawled out of a nightmare.

The man stood so abruptly that his chair collapsed behind him. He lurched towards them.

Ophelia hopped down into the vegetable patch.

Prue recoiled. For a few seconds she seemed suspended, twirling her arms in the air like a graceless hummingbird. Then she pitched backwards and thumped into the garden a few steps from Ophelia.

“Hurry!” Ophelia whispered. “Get up! He’s opening the window!”

Prue didn’t get up. She screamed. The kind of long, shrill scream you’d use when, say, falling off a cliff.

The man flung open the window. He yelled down at them in French.

“Get me off of it!” Prue yelled. “Oh golly, get me off of it!”

Ophelia crouched, hooked her hands under Prue’s arms, and dragged her to her feet. They both stared, speechless, down into the dark vegetation. Raindrops smacked Ophelia’s cheeks. Prue panted and whimpered at the same time

Then—the man must’ve turned on a lamp—light flared.

A gorgeous gown of ivory tulle and silk sprawled at Ophelia’s and Prue’s feet, embroidered with gold and silver thread.

A gown. That was all. That had to be all.

But there was a foot—mercy, a foot—protruding from the hem of the gown. Bare, white, slick with rainwater. Toes bruised and blood-raw, the big toenail purple.

Ophelia’s tongue went sour.

Hair. Long, wet, curled hair, tangled with a leaf and clotted with blood. A face. Eyes stretched open. Dead as a doornail.

Ophelia stopped breathing.

The thing was, the dead girl was the spitting image of . . . Prue.

2

The goggled man’s yelling stopped, and he vanished.

He’d be summoning the law. Or maybe unleashing a pack of drooling hounds.

Ophelia managed to stagger away with Prue from that horrible . . . thing. Prue’s whimpers inched into a hysterical register.

Ophelia lowered them both to a seat on the edge of a fountain. The fountain’s black water mirrored the lights of the party still going full-steam ahead inside. Those fancy folk hadn’t heard Prue’s screams through the piano music.

“Calm yourself. It will be all right.” Ophelia stroked Prue’s hunched back. These were hypocritical words, since Ophelia was feeling about as calm as a nor’easter herself. But what else could you say to a girl who’d just laid eyes on her dead double? “We’ll leave this place, Prue, just as soon as you’re able to walk. How would that be?”

Prue panted through her teeth.

“And that girl,” Ophelia said, “well, there must be some horrible mistake, or maybe—”

“How could it be a mistake? Them holes in her. The blood. The—”

“I don’t know. But we’ll leave, even if it means sleeping on a park bench, but first you must steady your breath, and—”

“My sister.”

“Sister? Have you a sister?” In all the years Ophelia had known Prue, she’d never heard of a sister.

“Had. I had a sister. Now she’s gone, and I never had a—had a—had a—” Prue crumpled into fresh sobs.

Her sobs were so noisy that Ophelia didn’t hear the scrunching gravel behind them until it was too late.

“You two,” someone said just behind them. “Mais oui. I might have guessed.”

Ophelia twisted around.

Baldewyn the steward minced around the fountain. Even in the dim light, it was easy to see his pistol, aimed straight at Ophelia’s noggin.

“You hold that gun just as prettily as a feather duster,” Ophelia said, “but doesn’t the hammer need to be cocked?”

“Forgive me,” Baldewyn said. “I had been inclined to think I was dealing with a lady. Not”—he cocked the hammer— “a sharpshooter. I had almost forgotten that you two are not only derelicts, but Americans. Does everyone in that wilderness of yours fancy themselves a—how do you say?—cowboy? S’il vous plaît, rise and walk.”

“Not on your nelly.”

“What a quaint expression. Does it mean no? Sadly, no is not, at this juncture, a possibility. The marquis has informed me that you have been trespassing, and that there appears to be a corpse on the premises. On occasions such as these, it is customary to take invading strangers into custody.”

“You aren’t the police,” Ophelia said.

“Oh, the Gendarmerie Royale has been summoned and the commissaire will be notified. You cannot escape. Now, I really must insist”—Baldewyn leaned around, pressed the barrel of the pistol between Ophelia’s shoulder blades, and gave it a corkscrew—“that you march.”

He prodded Ophelia with the gun across the garden to the house, Prue clinging to Ophelia’s arm all the way. They reached a short flight of steps that led down to a door. Windows on either side of the door guttered with dull orange light.

“The cellar?” Prue said. “You ain’t going to rabbit hutch us in the cellar are you, mister?”

Baldewyn’s answer was a shove that sent Ophelia and Prue slipping and stumbling down the mossy steps. Baldewyn followed. He kicked open the door, and bundled Ophelia and Prue across the threshold.

The door slammed and a latch clacked.

They were locked in.

* * *

Prue had reckoned she’d gotten ahold of herself. A slippery hold, leastways. But something about the sound of that latch hitting home made her go all fluff-headed again. Another scream bloomed up from her lungs, but it couldn’t come out. Her throat was raw now, wounded.

Wounded. Her sister. Those creeping dark stains. Her poor, small, battered foot.

“Look,” Ophelia said in the Sunday School Teacher voice she always used on Prue. “Look. It’s only a kitchen, see?”

Right. Only a kitchen. A mighty dirty kitchen.

“And,” Ophelia added, “it’s spacious. No need to feel cooped up.”

Half of the kitchen glowed from orange cinders in a fireplace. The other half wavered in shadow. Iron kettles on chains bubbling up wafts of savor and herbs. Plank table cluttered with crockery. Copper pots dangling from thick ceiling beams.

And . . . little motions flickering along the walls. Prue rubbed her eyes. The motions didn’t stop. Black, streaming, skittery—

“Mice!” she yelled.

In three bounds, Prue was on top of the table. Crockery crashed. A chair toppled sideways.

Mice. Uck. Prue’s skin itched all over. She disliked most critters with feet smaller than nickels, and she hated mice. Blame it on her girlhood, on the lean times spent in Manhattan rookeries.

“My sainted aunt.” Ophelia righted the chair.

“Sorry.” Prue crouched on the tabletop, arms hugged around her damp, muddy knees.

Ophelia, silent, stooped to collect shards of crockery.

Probably marveling at how she’d been dragged into yet another fix by Prue. Prue was fond of Ophelia, but she knew—or, at least, she powerfully suspected—that Ophelia looked upon her as a dray horse looks upon a harness and cart. A deadweight. A chafing in the sides.

Ophelia piled the crockery shards on the table. “Tell me about your sister,” she said. “Did you never know her, then?”

“Only heard stories. Well, just one story. Ma only kept her long enough for the one story, see.”

“What was her name?”

“Don’t know. She is—was—a year or two older than me. Her pa took her off when she was only a new baby. I never got to meet her, Ophelia, I—”

“What else did your ma say?”

“That’s all. That her pa was some hoity-toity French feller, and he hired a wet nurse and took the baby off to give her a better life. Didn’t want his child raised by an actress. Do you think . . . maybe Ma married him, all these years later? Maybe this here’s his house? But then, why is my sister lying dead out there in the weeds with those fine folks inside laughing and listening to piano songs and—”

“Shush, now. Don’t work yourself up.”

Prue patted her bodice. From beneath damp layers of wool and cotton came the comforting crackle of paper.

The letter. Her treasured secret. Proof that somebody in this wide world wanted her. Maybe.

* * *

Ophelia and Prue hunkered on stools at the kitchen hearth. They kept their wet cloaks and bonnets on. Their soaked boots steamed. Mice nibbled food scraps under the table.

From the rooms above came muffled voices, foot thuds, door slams. Outside in the garden, men’s voices rose and fell behind the spatter of rain on the windows. Lights shone and turned away like unsteady lighthouses.

More than an hour passed.

“Oh!” Prue’s head bobbed up. “Someone’s coming down the stairs.”

Ophelia straightened her wig and stood. “Let me do the talking.”

A person ought never show up to a murder wearing a disguise. Ophelia had realized that nugget of wisdom too late. The problem was that if one whipped off a wig and padded hips, say, shortly after a dead body was discovered, well, suspicions were sure to kindle.

Which meant there was no choice but to blunder forward in this absurd disguise.

Three men piled into the kitchen: the bald, egg-shaped fellow they’d seen tinkering with the screwdriver, and two young men in brass-buttoned blue uniforms. Police.

“Precisely what is the meaning of this?” Ophelia asked in her best Outraged Chaperone voice. “Locking us up like common criminals? I’ll have you know this is the marquise’s daughter, Miss Prudence Bright. Where is the marquise—where is Henrietta?”

The men gawked at Prue.

“I presume that your extremely rude staring,” Ophelia said, “is due to the simple fact that the dead girl in the garden is—was—also Henrietta’s daughter, and thus Miss Bright’s sister. The resemblance is indeed uncanny, but that is not an excuse to gape at this poor girl as though she were a circus sideshow.”

“Sister?” the egg-shaped man said. “Oh. Sisters. I see. I beg your pardon, madame. I have forgotten my manners. I am Renouart Malbert, the Marquis de la Roque-Fabliau. The master of this house.”

Malbert wore an elegant suit of evening clothes that was fifteen years out of mode and frayed about the cuffs and collar. He was so short he had to tip his custard-soft chins up to look into Ophelia’s face. His jeweler’s goggles had been replaced with round, gold spectacles. His eyes blinked like a clever piglet’s.

“Et oui, oh yes, mon Dieu,” Malbert said, “Mademoiselle Bright does indeed resemble the girl—her sister, you say—in the garden, and also my dear, darling, precious Henrietta.”

Henrietta was lots of things, but dear, darling, and precious were not at the top of the list.

“The girl in the garden, you say?” Ophelia frowned. “Then you do not know her name?”

“Why, no,” Malbert said. “She is a stranger to me.”

“A stranger!”

“Yet now that I see this daughter—Prudence, you say?—of my darling wife, well, now I begin to discern a family resemblance. Oh dear me.” Malbert dabbed his clammy-looking pate with a hankie. “A most perplexing matter, troubling, macabre, even.”

“I should say so,” Ophelia said. “Perhaps the girl was searching, too, for her mother at this house.”

“Are you a relation of dear Henrietta’s, as well?”

“No, I am . . .” Ophelia cleared her throat. “I am Mrs. Brand. Of Boston, Massachusetts. Miss Bright could not, of course, travel without a chaperone. She is young, and quite alone. I encountered her by chance, degraded to the role of maid by an appalling series of events, in the scullery of an American family residing in Germany. I agreed to escort her, out of a sense of national duty and womanly propriety, to her mother here in Paris.” Half-truths, and a couple of whoppers. But Ophelia couldn’t very well say she was an actress, too, because that would mean rev

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...