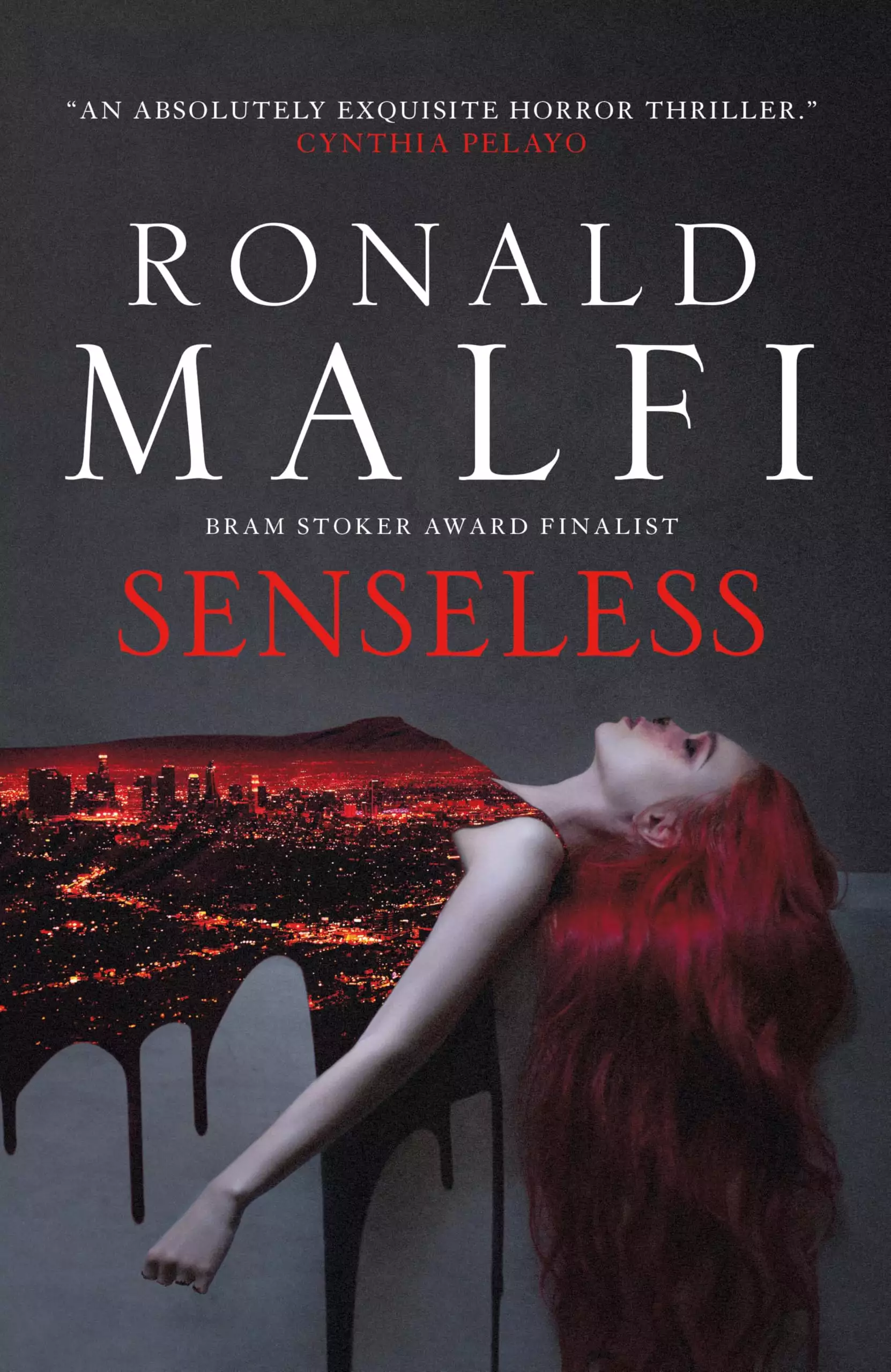

Senseless

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

What do you see...?

When the mutilated body of a young woman is discovered in the desert on the outskirts of Los Angeles, the detective assigned to the case can't deny the similarities between this murder and one that occurred a year prior. Media outlets are quick to surmise this is the work of a budding serial killer, but Detective Bill Renney is struggling with an altogether different scenario: a secret that keeps him tethered to the husband of the first victim.

What do you hear...?

Maureen Park, newly engaged to Hollywood producer Greg Dawson, finds her engagement party crashed by the arrival of Landon, Greg's son. A darkly unsettling young man, Landon invades Maureen's new existence, and the longer he stays, the more convinced she becomes that he may have something to do with the recent murder in the high desert.

What do you feel...?

Toby Kampen, the self-proclaimed Human Fly, begins an obsession over a woman who is unlike anyone he has ever met. A woman with rattlesnake teeth and a penchant for biting. A woman who has trapped him in her spell. A woman who may or may not be completely human.

In Ronald Malfi's brand-new thriller, these three storylines converge to create a tapestry of deceit, distrust, and unapologetic horror. A brand-new novel of dark suspense set in the City of Angels, as only “horror's Faulkner” can tell it.

Release date: April 15, 2025

Publisher: Titan Books

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Senseless

Ronald Malfi

PART ONE:HIGH DESERT

ONE

Once, when Bill Renney was a teenager, he had been bitten by a Southern Pacific rattler while partying with some friends in Antelope Valley. He hadn’t seen the thing at first, merely heard the ominous, inexplicable maraca of its tail, then felt the hammer-strike against the bulge of his left calf muscle. He had just set down an Igloo cooler full of beer and ice beside an outcropping of bone-colored stone when he felt the bite, and for a moment, in his confusion, he thought he had snapped a tendon in his leg. But then he saw the beast— four feet of sleek brown musculature retreating in a series of s-shaped undulations across the sand—and he knew he was in trouble.

His friends had loaded him into the back of a Jeep where someone tied a tourniquet fashioned from a torn shirtsleeve above the wound to slow both the bleeding as well as the progression of venom through his bloodstream. Renney pivoted his leg and could see blood spurting from twin punctures in the otherwise pale, mostly hairless swell of muscle, in tandem with his heartbeat, and the sight of it made him woozy. As the Jeep sped across the desert toward civilization, Renney could feel a burning sensation traveling from the puncture marks up his leg, combined with a moist, roiling nausea in his gut. By the time the Jeep pulled up outside the nearest medical facility, Renney was vomiting over the side.

The experience—now over three decades in the past—had left behind a pair of faint white indentions in the tender meat of Bill Renney’s left calf. It had also left him with a healthy respect for the desert, and for all manner of creatures that resided there.

On this morning, the desert was alive. As he drove, large black flies swarmed in the air, and he periodically turned the windshield wipers on to swipe their smudgy, bristling carcasses from the glass. Beyond the shoulder of the road, the occasional coyote would raise its head and scrutinize the passage of Renney’s puke-green, four-door sedan as it rumbled along the cracked, sun-bleached pavement. When he finally eased the sedan to a stop, he could see the boomerang silhouettes of carrion birds wheeling across the bright blue tapestry of the sky.

Two L.A. County Sheriff’s Department SU Vs and a few Lancaster cruisers were parked on the shoulder of the desert highway, their rack lights on. An ambulance sat at a tilt off the blacktop, next to a solitary green road sign that read, simply, LOS ANGELES COUNTY LINE. Two paramedics and a uniformed officer stood before the open rear doors of the ambulance, their faces red and glistening from the heat of the early morning, the chrome plating on the ambulance reflecting the sun in a spangle of blinding light. Farther up the road was an old Volkswagen bus, sea-foam green except for where the scabrous patches of rust had taken over. One more officer stood there, talking to a young couple who looked like Woodstock refugees. Beside the bus, bright pink road flares sizzled in the center of the roadway, but they were nothing compared to the sun that blazed directly above the desert.

Bill Renney popped open the driver’s door of his unmarked sedan and swung his feet out onto the blacktop. With a grunt—he really needed to get back to the gym and lose the burgeoning spare tire that had been expanding around his waistline this past year, ever since Linda had passed—he bent forward and tucked the cuffs of his pants into his socks. Much like everything else out here in this desolate wasteland, the ants could be merciless.

He got out of the car, swung the door closed, then casually swept aside his sports

coat so the officer and the two medics standing by the ambulance could glimpse the gold shield clipped to his belt, right beside the nine-millimeter Smith & Wesson M&P. The officer nodded at Renney then went back to talking to the paramedics. Flirting, Renney thought.

He nodded, too, at the uniformed officer standing with the couple beside the VW bus. The couple was young, the guy maybe in his early twenties, sporting ratty Converse sneakers and a tank top with marijuana leaves embroidered across the front. He had what looked like tribal tattoos on his biceps and the feathered blonde hair of a surfer. The woman standing beside him looked even younger— nineteen at best, if Renney had to guess—and she was wearing a loose, cable-knit shawl over a neon-green bikini top, and, despite the rising heat of that early morning, appeared to be shivering. They were both in handcuffs.

Renney stepped between the two SUVs and out onto the valley floor, where the blacktop gave way to hard-packed sand, spiky tufts of sagebrush, sprigs of desert parsley, and the prickly pompoms of scorpionweed. The sun was high and bright and directly at his back, stretching his shadow out ahead of him along the rippling contours of the earth, and making it appear as though he were traversing some alien landscape. He could feel the intensity of the morning sun as it bore a hole in the center of his back.

He was suddenly craving a cigarette.

A group of uniformed officers stood beyond a scrim of sagebrush. They were maybe thirty, forty yards from the road, but their collective stare as Renney approached was undeniable, even from such a distance. Renney could see that they were all wearing paper masks over the lower half of their face, just like people did back when that whole COVID shit started.

“Detective Renney,” one of the officers called to him, the man’s voice slightly muffled behind the paper mask.

Renney checked his watch as he advanced toward the officers and noted that it was just barely after seven in the morning. He took another step, and a horde of blowflies was abruptly congregating around his head; he absently swatted at the air in an attempt to disperse them, bobbing and weaving his head like a prizefighter. Another step, and a prong of sagebrush grazed his thigh, thwick, causing him to jump and take a quick step to the side. He searched the ground at his feet for any signs of snakes.

“Watch out for the anthills, too,” one of the other officers called to him, pointing toward Renney’s shoes.

Renney froze in midstride. He glanced down again and saw crumbly mounds rising up from the desert floor like booby traps. Beyond the anthills, a set of tire tracks wove a clumsy arc across the floor of the valley. He made a mental note of the tracks as he stepped over them, careful not to disturb any potential evidence.

“We called dispatch first, but Politano here suggested we ask for you by name,” said the muffle-voiced officer who had warned him about the anthills.

Politano?” Renney asked.

A young-looking male officer with short, raven-black hair raised his hand. “That’d be me, sir. I remembered you from last year. Your name, I mean. We met briefly at a press conference.” His voice was also muffled behind the paper mask; Renney realized now that they were wearing them to keep the blowflies out of their mouths.

“Right,” Renney muttered, although he did not recognize the young officer with the mask on. “So, what’ve we got?”

“She’s maybe in her early to mid-twenties, if I had to guess,” said Officer Politano. “We didn’t check for any ID or anything. Frankly, sir, we didn’t want to do anything until you got here.”

Officer Politano nodded down at the reason Bill Renney had been summoned all the way out here so early this morning.

There was a body on the ground. Adult female. Caucasian. Beneath the unforgiving glare of the sun and through a cloud of frenzied flies, Bill Renney could make out a turquoise halter top, and a pair of faded denim shorts that were frayed to tassels at the hems. What at first looked like a bruise on the left thigh was actually a tattoo of a rose, with a tendril of thorns running down the length of that pale, fly-bitten leg. The feet were bare, but a bit of gold jewelry caught a sunbeam and sparkled along one slender ankle. The woman’s head was turned at an angle away from Renney, so that he only saw the nest of dusty, knotted blonde hair at the back of her head. The one arm that he could see from his vantage was crooked in a position that propped the left hand into the air. All five fingers from that hand were missing, the wrist and forearm stained in striations of dark blood.

A sinking sensation overcame Bill Renney. It felt like he was suddenly plummeting down an elevator shaft.

Jesus Christ, he thought. What the actual fuck?

“Those two up by the road spotted the body about an hour ago,” said Officer Politano, who nodded in the direction of the VW bus and the young couple in handcuffs being questioned by the police officer at the shoulder of the highway. Politano lowered his mask and Renney saw that he was indeed young and fresh-faced, and he thought maybe he did recognize him after all. Maybe from Palmdale, although he couldn’t be sure. “They were driving by, doing a little day-tripping, when they saw vultures circling something on the ground,” Politano went on. “Guy said he could tell it looked like a person out there, and his girl agreed. He got out and had a look. Then the girl, she called it in on her phone. We asked them to wait for us to arrive, and they did. The girl said they kept honking the horn to keep the vultures away, which mostly worked.”

“Why are they in bracelets?” Renney asked.

“Well, they gave us permission to search the van. We found some coke.”

Renney stepped around to the other side of the body.

He wanted to see

the face.

“The body probably hasn’t been out here for very long,” Officer Politano continued. “A few hours, tops. The vultures haven’t done a job on it yet.”

No, the vultures hadn’t, but this close to the body, Renney could see large red ants coursing up and down the corpse’s pale thighs, flossing between the exposed toes with their dark blue nail polish, and creeping in a conga line across the bloodstained front of the turquoise halter top. The blowflies, too, had collected in the corpse’s hair, so plentiful that Renney could hear their orchestral hum.

He knelt beside the dead woman’s head.

Jesus Christ.

A second officer cleared her throat and said, “We thought maybe coyotes could’ve—”

Renney shook his head. Said, “No.” Said, “Coyotes didn’t do this.” Then he turned his head and spat tiny flies from his mouth.

“I didn’t think so, either,” said Politano. Something clicked in the back of the young officer’s throat as he said this. He’d kept his mask down around his neck, as if in solidarity with Renney.

The dead woman’s nose and eyes had been removed, leaving behind a trio of empty, bloodied sockets. This gave the corpse’s face a disconcerting jack-o’-lantern appearance, albeit one smeared in a crimson sheen of dried blood. Ants swarmed all over while some large beetle with an iridescent carapace lumbered along the rise of a stone-white cheekbone—the only part of the corpse’s face that was not covered in blood. Renney was cautious not to touch the ants as he reached down and brushed aside a tuft of tangled blonde hair. Blowflies exploded in a smoggy cloud and disseminated into the air.

Son of a bitch, Renney thought, just as a nasty muscle tightened in the center of his chest.

The woman’s left ear had been removed, as well. Both ears, Renney assumed, although he could only see the one side of her head at the moment. There was dried blood along the neck, too, and the skin there had purpled, but the flies were not making the area easy to study.

“I saw this and I thought of that other one,” said Officer Politano. “That woman from last year, I mean.”

Last year, Renney thought, and he could feel a cool sweat dampen his brow. Son of a bitch.

“The fingers look like they were sliced off with a knife or a razor or something, maybe bolt cutters,” Officer Politano continued, then he glanced at the other officer, and added, “Not coyotes.”

Renney said nothing, but Officer Politano was correct. Same with the nose—it had been removed, along with all the cartilage, from around the nasal and vomer bones. The eyes had been gouged

out of their sockets, while the one missing ear that Renney could see had been sliced away like someone sliding a sharp, hot blade across a brick of butter.

“You were the lead on that case?” the female officer asked him.

“I was,” Renney said, thinking now, I am. “Is that a helicopter?”

“What, sir?”

Renney raised an index finger above his head, in the approximate direction of the sound of incoming rotors. He did not take his eyes off the body.

“Oh,” said the officer. “Yes, sir. They’re searching the area.”

“Radio in and tell them to keep away. I don’t want them blowing sand all over the place.”

“Yes, sir,” said the officer, and then she was jogging back to one of the SUVs.

“Any footprints in the vicinity?” Renney asked the remaining officers.

“Only the guy’s footprints from when he came out here to have a look at the body,” said Officer Politano, once more nodding in the direction of the Volkswagen bus and at the young couple in handcuffs. “Prints matched the treads on his sneakers. We took photos. No one else’s that we could see.”

“Night winds blow the sand around, cover things up. How far out did you check?”

“I personally canvassed about a hundred square feet around the victim before you got here.”

“They see anyone else out here while on their drive?”

“The couple in the van? No. Not a soul, sir.”

“What about any vehicle tracks in the sand? You guys find any?”

“No, sir.”

“I noticed some tire tracks over by those anthills.”

A beat of silence simmered in the air between the officers.

Renney looked up at their dark silhouettes plastered against the inferno of a blazing desert sun. He lifted an arm to shield his eyes from the glare. Sweat rolled down his face.

“That was me,” confessed one of the other officers, who had also removed his paper mask now—another guy Renney thought he recognized from Palmdale. Or maybe Lancaster. These young guys all looked the same. “I drove out here when we first arrived on scene, sir, but then thought, well . . . I mean, I went back up to the road . . . I realized I’d compromised the scene, sir, I just . . . I wasn’t thinking . . . ”

“Someone go unhook those two,” Renney said, jerking his head in the direction of the Volkswagen and the two hippies.

“Uh, sir,” stammered one of the officers. “They had about two grams of cocaine in their—”

“I don’t give a shit about the coke. Unhook them and ask them to come down to the station to give a proper statement. Do it before they manage to rub together whatever brain cells they still have between them and ask for a lawyer.”

“Understood,” said the officer, already moving back toward the road.

Renney looked back down at the corpse’s mutilated face. From the inside pocket of his sports coat, he pulled out a pair of latex gloves and tugged one on. He brushed away the swarm of ants along the lower half of the corpse’s face, then pressed his thumb to the chin. He gently lowered the jaw until the mouth hung open, then peered into the cavity.

“Tongue’s gone, too, isn’t it?” asked Politano.

“It is,” Renney confirmed. Indeed, it had been severed, leaving behind a pulpy, bloodied stump. Not as neat and clean as the removal of the nose, ears, and eyes. Harder to get at, he supposed. As he stared at what remained of the tongue, a rivulet of ants spilled out from one corner of the corpse’s mouth, and Bill Renney yanked his hand away, the thumb of his latex glove sticking briefly to the dried blood on the chin before releasing with an audible snap.

“She’s cut up the same way as that other woman from last year,” said Officer Politano, and it was not phrased as a question. Something clicked once more in the young man’s throat. “Isn’t that right, detective?”

Renney exhaled audibly as he rose to his feet. His armpits felt swampy, his throat dry. He still craved that cigarette. As he dusted the sand from his knees, Officer Politano’s handcuff chain rattled, and the hairs on the back of Renney’s neck stood at attention. He glanced around for any evidence of approaching rattlesnakes.

“Detective Renney?” Politano said, perceptibly clearing his throat. “She’s in the same condition as that other woman we found out here a year ago. Isn’t that right, sir?”

“It would seem that way,” Bill Renney admitted, and to his own ears, it sounded like a confession.

* * *

The chief M.E. with the County of Los Angeles Department of Medical Examiner was a tall, sterling-haired man in his late fifties, named Falmouth. He reminded Renney a little bit of Pierce Brosnan without the accent. According to Falmouth, the parts of the victim that had been removed—her nose, eyes, ears, tongue, and the fingers and thumbs of both hands—had been done so postmortem. There had been two implements used to remove these bits: a crude blade, like some dulled hunting knife or razorblade, had been employed to dig out the eyes, and carve away the nose and ears. Possibly the tongue, too, Falmouth concluded. The fingers and thumbs, on the other hand (“No pun intended,” Falmouth muttered stoically), appeared to have been removed with an altogether different implement—something, according to the medical examiner, like a set of bolt cutters. Just as Officer Politano had surmised, Renney noted.

“Tell me,” Renney said. “Tell me—what are the differences between this

body and the one from last year.”

“Quite a few, actually,” said Falmouth, “from a forensic standpoint, at least. For one thing, the cause of death is different. The woman from last year died from exsanguination—blood loss from her wounds. This victim, however,” he said, and he peeled back a layer of white sheet to expose the corpse’s face, now mostly swabbed clean of the dried blood by rubbing alcohol, yet still looking skeletal with its missing pieces, “died of asphyxiation. Look—see here?”

With one latex-gloved finger, Falmouth addressed a vague gray outline around the corpse’s nasal cavity and mouth. To Renney, it looked like dirt or some other debris.

“What is that?” he asked.

“Remnants of some adhesive,” said Falmouth. “Something sticky had been placed over her mouth and nose, causing her to suffocate. After she was dead, her killer went to work on her.”

Renney leaned closer and examined the gray flecks of adhesive around the corpse’s mouth and nasal cavity. He hadn’t noticed them back in the desert when he’d first studied the body, given all the dried blood and blowflies swarming around the corpse’s face, but he could see it clearly now.

“All adhesives contain long chains of protein molecules that bond with the surface of whatever they’re sticking to,” Falmouth explained. “I’ve already scraped some off, sent them to the lab.”

Renney nodded.

“There are ligature marks around the wrists and ankles, too,”

Falmouth went on. “This woman was bound at some point. That differs greatly from

the body we examined last year, as well, which showed no signs of that victim being bound or even held against her will.”

“Can you tell what was used to bind her?”

“I’ll have the lab confirm that, as well, but I’m guessing some sort of rope, based on the fibers I extracted from the abraded flesh. At least on the wrists, anyway.”

“Her feet were bare when we found her. Maybe you can check the soles of her feet to see if you can determine what sort of location she might have been kept in?”

“Already have. Just your basic dirt and grit, I’m afraid.”

“Right,” Renney said.

Falmouth reached over the body splayed out on the stainless-steel table and gently turned the corpse’s head on its neck. Renney imagined he could hear the tendons creak. The blonde hair had been shorn away close to the scalp, and despite the Braille-like topography of the skin due to countless insect bites and exposure to the cruel elements of the desert, Bill Renney could clearly make out the ragged cut around the ear canal.

“All these amputations are a little hastier than the ones on the previous victim,” Falmouth explained. “See how the flesh pulls away, as if the ear was only partially severed but then torn the rest of the way, maybe by someone pulling at it? Do you see how it was ripped here? The way the flesh pulls down toward the jaw line, like a hasty rip. These little loose strands of jagged flesh?”

“Yeah, I see,” Renney said, following Falmouth’s latex-gloved finger as it traced the wound.

Falmouth lifted one of the corpse’s arms by the wrist. “Same with the fingers. The cuts from last year were made precisely at the junction of the middle and proximal phalanx. These amputations are hastier; the implement used cut straight through the bone and not at the joint.”

Renney stared at the irregular shards of bone poking up from what remained of the fingers.

“The woman that was found last year had all these elements removed from her in an almost surgical fashion. The person who had done that had been careful. Precise. Artful, almost. A scalpel was used, was my conclusion, except for the fingers, where I believe the assailant had utilized something more proficient to break through the carpometacarpal joints—something like a sturdy hunting knife or something of that ilk. The amputations on this victim are much cruder, which I find interesting, since they were removed postmortem where her assailant could have taken his time.” Falmouth shrugged, placing the wrist back on the table, then added, “But those differentiations could just be circumstantial.”

“Meaning what?” Renney asked.

Falmouth arched his slender, steel-colored eyebrows. “Meaning the killer could have been in a hurry this time, for whatever reason.”

“What about any fingerprints or DNA left behind?”

“No fingerprints from the assailant that I’ve been able to find, which just means he could’ve been wearing gloves. I’ve swabbed the body for trace DNA, found some hair follicles and evidence of desquamation—the shedding of dead skin cells—but so far there haven’t been any hits. It’s possible the assailant isn’t in the system.”

“That’s a big difference from last year, too,” Renney said, although more to himself than to Falmouth. The crime scene last year had been impossibly clean, with no trace DNA left behind. “So, do you think this is the same guy who killed that woman last year?”

“Anything’s possible,” said Falmouth, spreading his arms. “The details of how the first victim was found were—”

“Those details never made it to the press,” Renney finished. “Right.”

“Exactly. So, in my estimation, to have all these same . . . elements . . . removed in such a similar and specific fashion, not to mention the location where the body was found—”

“Yes,” Renney said, cutting him off. “I understand what you’re saying. A copycat killer wouldn’t know those details because they were

never public.”

“It’s just that even with the discrepancies, Bill, the similarities are all there. I wouldn’t bet on a coincidence, is what I’m saying. But you’re the detective.”

Renney pointed to a darkened, mottled tract of flesh along the victim’s thigh—something that hadn’t been there when he had first come upon the body in the desert, because now the rose tattoo was incorporated into that bruising, which hadn’t previously been the case. He would have noticed. “What’s all that?” he asked. “Are they bruises?”

“This?” Falmouth said, tracing the pattern of darkened flesh along the victim’s thigh. “We call this discoloration a ‘postmortem suntan.’ Dead skin cells react differently to the sun’s U V light.”

“I once dated a girl like that,” Renney said. The comment made Falmouth chuckle, but Renney could still feel some expanding discomfort uncoiling in the center of his chest. He kept hearing Falmouth’s words echoing in his head: It’s just that even with the discrepancies, the similarities are all there . . .

“I would conclude that this body was left in the desert sometime just before dawn,” Falmouth said. “The coyotes and vultures hadn’t gotten to it yet. Bugs will do damage at any hour, but birds and mammals tend to wait a while to make sure what they’re going after is actually dead. Still, you’re looking at maybe a three- to five-hour window, at best. Probably less.” Falmouth cleared his throat then added, “The desert is unforgiving to a body.”

Renney thought of the countless bovine skeletons that littered the desert floor, straight out to the Mojave, all the way out to Las Vegas. Thought of the pinwheels of vultures that were always visible somewhere on the horizon, waiting patiently for some poor thing to expire.

That terrible muscle in the center of his chest constricted again.

Fifteen minutes later, as Renney walked slowly down the long, tiled, echo-chamber corridor of the DMEC, he happened to glance up at a television mounted on brackets to the wall. On the screen was a newscaster standing before the solitary green road sign that read LOS ANGELES COUNTY LINE, an expanse of high desert in the background. The chyron at the bottom of the screen said: BODY OF FEMALE VICTIM FOUND MUTILATED IN ANTELOP VALLEY.

“ . . . where, less than a week ago, the body of an unidentified young woman was found mutilated in the spot you see right over my

shoulder,” said the reporter. “For the people who live out here, they are reminded of an eerily similar murder from the year before— that of thirty-two-year-old Melissa Jean Andressen, whose body was discovered in this very stretch of desert.”

A still image of Melissa Jean Andressen appeared on the screen, and Renney recognized the photo as the same one the department had circulated to the media in the days after her body had been discovered last year—an attractive woman in tennis whites, dark hair as full as a lion’s mane around her head, smiling beatifically. Her eyes were green and radiant and heavily lashed. She had been very pretty, Renney thought.

“Andressen’s killer was never brought to justice, despite the efforts of the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department and the hefty reward posted by Andressen’s husband, prominent Hollywood psychiatrist Dr. Alan Andressen.”

Melissa Jean Andressen’s photo was replaced by one of her husband. Alan Andressen was smiling, too, only there was something reserved about it—as if smiling did not come naturally to the man. Renney supposed that was true, although he knew it was unfair to pass such judgment, since he’d only known Alan after the murder of his wife, when the man was at his worst.

“For a while,” the reporter continued, “Dr. Andressen was the only suspect in the murder of his wife, but he was ultimately cleared by police early in the investigation. Now, with the discovery of this new victim, locals and police alike are starting to wonder if the two murders may not be connected. As for any specific similarities that might connect these two murders, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has not released any details to the media. Sarah Sullivan, Channel Eleven News.”

The broadcast switched to sports, but Renney hardly noticed. There was a tunneling in his vision now, coupled with an eerie auditory exclusion. He’d been in two shootouts during his tenure on the force, and the way time seemed to slow down and stretch, providing only a pinpoint of light at the end of his narrowing vision, like staring down a long tunnel, was very similar to how he now felt.

He stood there, sweating.

* * *

Her name was Gina Fortunado, twenty-six years old, originally of San Bernardino, California, but recently having resided in a one-bedroom apartment in downtown Los Angeles. A schoolteacher, single, and a graduate of UCLA, she was last seen by some girlfriends the day before her body was discovered, while they all had lunch at some vegan joint on Alameda Street. No one that Bill Renney could readily identify—including the girl’s parents, who still lived in San Bernardino—had seen her since.

He visited her parents at their modest, single-family home on Magnolia Avenue—a cheery stamp of property bracketed by towering palm trees and with a cluster of vehicles in the driveway. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...