Ghostwritten

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

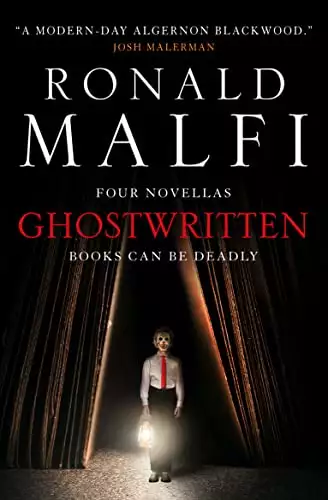

Four brand-new horror novellas from "a modern-day Algernon Blackwood" all about books, stories, manuscripts—the written word has never had sharper teeth . . .

BOOKS CAN BE DEADLY

In The Skin of Her Teeth, a cursed novel drives people to their deaths.

A delivery job turns deadly in The Dark Brothers' Last Ride.

In This Book Belongs to Olo, a lonely child has dangerous control over an usual pop-up book.

A choose-your-own adventure game spirals into an uncanny reality in The Story.

Full of creepy suspense, these collected novellas are perfect for fans of Paul Tremblay, Stephen King, and Joe Hill.

Release date: October 11, 2022

Publisher: Titan Books

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Ghostwritten

Ronald Malfi

1

We’ve got a problem,” said Jack Baer. They were the first words out of his mouth, even before he sat down at the table. Gloria eyed him coolly as she steeped her tea. They were at Antoine’s—Jack’s request—and the breakfast crowd was queuing up at the door and curling around the block on this warm September morning. Jack Baer queued for no one; in fact, he seemed oblivious to the people filing into the restaurant all around him. Gloria Grossman had known Jack for the better part of a decade, though his reputation in the industry had preceded any formal introduction. He’d been a top player at CAA before opening his own boutique literary agency, and he had, from time to time, courted Gloria, enticing her to join him. Merger, was how Jack put it, framing the word in the air with his big hands to get her to visualize the marquee. But Jack had a reputation for representing difficult clients, which presented a whole host of headaches Gloria did not feel like shouldering. Ironically, it was her client, the screenwriter Davis McElroy, who was the cause of today’s meeting, and any headache that would inevitably follow.

“Hello to you, too, Jack,” Gloria said, plucking her teabag from the cup and tucking it along the rim of the saucer.

“I’m sorry, Glor,” Jack said, reaching across the table and squeezing her hand. “I’m a bit frazzled this morning. How’ve you been? How’s Becca? Is everyone well?”

Gloria pulled her hand out from beneath his, enjoying the sound of his heavy Rolex knocking against the tabletop.

A waiter came over and Jack ordered an espresso and a bagel.

“Davis McElroy,” Jack said, once the waiter had departed. “What are we going to do here, Glor? Any word from him? Please say yes.”

“No, I haven’t heard from him.” She was careful not to make it sound like some sort of admission of failure on her part. Also, she was cautious not to allow her own aggravation to show. If she was going to curse her client, she’d do it in private.

Jack cleared his throat. “Haven’t you tried to reach—”

“Of course I have,” she said, cutting him off. “I’ve sent emails, I’ve left voicemails. Although I’ll be honest, Jack—it’snot unusual for him to be unresponsive when he’s up at the house working on a project.”

“Is he, though?” Jack said, arching one slender, steel wool eyebrow. “Is he working on the project? Because he’s a month past his deadline and the studio doesn’t want to renew the option. Not with McElroy attached. He’s been MIA for several weeks, maybe more, from what I can tell, and the execs aren’t getting the old warm and fuzzy anymore. He’s put the whole project in jeopardy.”

“Don’t exaggerate, Jack,” she said, and now she reached out and squeezed his hand, grinning condescendingly. Don’t play me, Jackyboy, she thought. Thing was, Jack Baer was right—Davis McElroy had been MIA. Hell, McElroy might have fallen off the face of the earth for all Gloria knew at the moment. She hadn’t heard from McElroy in over a month, he’d missed his last few scheduled Zoom meetings with the studio execs at Paramount, and he had been unresponsive to Gloria’s repeated emails and phone calls warning him that his deadline to turn in his draft of the screenplay had come and gone and that the option period was coming to a close, too. Had it been another one of her former clients—old George Lee Poach, for example, who was infamous for his cocaine-fueled benders and periods of reclusiveness—Gloria wouldn’t have been surprised. But Davis McElroy had always exhibited a steadfast work ethic and he’d never missed a deadline. He was also six or seven years into recovery, and as far as Gloria Grossman knew, he no longer ingested anything more potent than ibuprofen. True, he did not like to be bothered when he went up to the house—the Hole in the Wall, as he called it—towork on a project, but even his time up there had never precluded him from returning her calls or responding to her emails. Was it possible he’d fallen off the wagon? Lord knew Gloria had seen it a million times before. It was a goddamn cliché in this industry, and hardly the most unexpected thing to happen to a writer.

“Mr. Fish has also attempted to reach out to him personally,” Jack said.

“The illustrious John Fish makes personal phone calls? I just assumed you did all the dialing for him, Jack. Just like you cut and chew his filet mignon.”

“Quip all you want, Gloria, but that should clue you in to the severity of the situation.”

“I’m not quipping, Jack. I just don’t want you to pop a gasket.”

Jack frowned, rubbed a set of plump, hairy-knuckled fingers across the mottled ridge of his brow. John Fish was just the type of client that dissuaded Gloria from merging her agency with Jack’s—the epitome of the pampered, pompous novelist, who’d spent the bulk of his career marinating in white male privilege. She’d heard rumors that, while on a book tour, Fish insisted his hotel rooms be cleaned by his own team of hired professionals, and that the rooms themselves be stocked with a supply of assorted nuts, dried fruits, charcuterie, a vase of fresh daisies, scented toilet paper, and bed sheets whose thread count was never to be lower than a thousand. He was an asshole, in other words. But John Fish—and Jack, for that matter—was right to be concerned. Davis McElroy had been hired by the studio to adapt Fish’s bestselling novel, The Skin of Her Teeth, and he hadn’t delivered. It was a mess all the way around.

“Is it possible something could’ve happened to the guy out there?” Jack continued. “Could he have had a heart attack or a stroke or something out there at the house?”

“He seemed in good health to me, last time I saw him,” Gloria said. Anyway, it wasn’t a heart attack or stroke she was worried about. To the best of her knowledge, McElroy didn’t attend NA or AA meetings while tucked away up there in the Hole in the Wall like he did when he was here in the city. Maybe the damn fool had slipped up.

“Well, somebody needs to get in touch with the son of a bitch,” Jack insisted. “Maybe you should call the local police up there, have them drop by for a welfare check or something. Make sure the poor bastard isn’t lying dead on the floor and that his dog hasn’t made a meal of his corpse.”

“I don’t believe he has a dog.” It was meant to be humorous, but it missed the mark.

“I wish I could share your confidence here, Gloria. Whatever is going on, it’s bad business, and it’s making Fish uncharacteristically… let’s say, itchy?”

Gloria laughed. “Itchy, huh?”

“He’s troubled by this whole thing. He keeps asking if we’ve heard from McElroy. It’s not like him to give such a shit, to speak frankly. I didn’t even think he knew Davis McElroy’s name, let alone the guy’s phone number.”

Jack’s espresso and bagel arrived, borne on a linen-covered tray. The waiter set the items on the table and Jack picked up the espresso, his squat, rectangular pinky extended. The cup looked like a miniature novelty in his oversized hand.

“No one’s calling the police,” she told him. If McElroy hadrelapsed, she didn’t want to invite any legal complications into the equation. McElroy could be up there feasting on a buffet of cocaine and Jim Beam, for all she knew. Cops would just muddy the waters. “But I agree that enough’s enough. I’ve already made up my mind to go out there myself and check up on him.”

Jack’s eyes widened over the rim of his espresso. “To the house?” he said, setting the cup down.

“It’s not Beirut, Jack,” she said. She’d been up to the Hole in the Wall on a few occasions, whenever McElroy would throw one of his solemn, somewhat self-pitying get-togethers. She had the address in her phone. It was only a few hours’ drive, and it would do her good to get out of the city for a while. She didn’t own a car, though, so she’d have to butter up to Becca.

Jack just shook his head. “This whole thing sets me on edge,” he commented, gazing at the traffic in the street now. His small eyes darted here and there, here and there. “I don’t want to lose this deal.”

“We’re not going to lose the deal. I’ll handle it, Jack. In the meantime,” she said, “you take care of the studio. Keep them placated and on the line. I’ll deal with McElroy. I won’t come back from that house without the script.”

“And what if he hasn’t written the damn thing?”

“You’re such a pessimist, Jack,” she said, but was already thinking the exact same thing.

2

“A day trip,” Becca said, not a question, half-moon glasses perched along the edge of her slender, ski-slope nose. Seated behind an economical aluminum desk—ugly but functional, Gloria supposed—in her office at the university, Rebecca Carroll looked every bit the career academic she’d been for the past two decades.

Somewhat of a bribe, Gloria had brought Becca lunch—abean sprout and avocado sandwich on rye and a kale shake from Antoine’s—and she watched as Becca alternated between nibbling the sandwich and consulting an imposing textbook splayed open on her desk. Behind her, a pair of bookshelves, dense with heavy leather-bound volumes, looked like they might avalanche down on Becca at any moment.

“I wish it was as pleasant as it sounds,” Gloria said, and then she explained the situation with Davis McElroy. Becca remembered McElroy and knew of McElroy’s house upstate, too—she’d been Gloria’s date at one of McElroy’s tedious soirees—but she professed concern with the notion of Gloria traveling out there on her own.

“If this guy is messed up on drugs or something, I’m not sure it’s the smartest thing in the world for you to go waltzing right into the middle of that, Glor,” Becca said.

“Worst-case scenario, he’s strung out and needs a cold shower,” Gloria said.

“No,” Becca countered, glancing up from the textbook. “Worst-case scenario, he’s dead. Or he comes at you swinging a hammer because he’s blotto on smack and thinks you’re Julius Caesar.”

Gloria laughed. “‘Blotto on smack’? Where’d you glean that gem of a phrase?”

“Laugh if you must, my dear, but you know I’m right. Why not wait for the weekend? We can drive up together. Make a mini-vacation out of it.”

“What’s that word? ‘Vacation’? Sounds vaguely familiar…”

“A nice stay at a bed and breakfast, with those crumbly biscuits and a veritable library of teas,” Becca continued.

“Sounds nice, but this can’t wait. The studio doesn’t want to extend the option. But I’m hoping that if he’s actually written the damn screenplay, I can deliver it and maybe salvage this whole thing.”

“You really think that’s a possibility?”

“That I can salvage this thing?”

“That he’s actually written it. I mean, it would be awfully considerate of the guy to postpone his alleged coke-binge until after he’s finished the screenplay, but I seriously doubt that’s the case. Addicts aren’t generally known for their accountability.”

“Well, I can’t just throw my hands up in the air and do nothing, Becca. There’s a lot riding on this deal. Besides, that’s just not my style. You of all people know that.”

Becca sighed audibly. She closed her book and wrapped the remaining half of her sandwich in the crinkly brown paper it came in. “Yes, right, I know that, Glor. I’m just concerned, that’s all.”

“And I really think it will be fine. Now—can I please borrow your car?”

“Of course,” Becca said, scooting back in her chair and sliding open a desk drawer. “But I also want you to borrow something else.”

The thing Becca placed on the desk looked like a black metal pipe, about four inches in length. It was an expandable baton, like the kind police officers carried. Technically illegal in New York, but Gloria knew Becca didn’t much care for laws that impinged upon her personal safety.

Gloria shook her head and smiled. “Aw, Becca, your Penis-Be-Good stick. However will you keep rapists and similarly unsavory characters from assaulting your person as you walk home?”

“Don’t patronize me, Gloria. Take the damned thing. Who knows what’s happening up at that house? You may need it more than me. And listen—give me a call when you get there, okay? Not that I’m trying to smother, I just want to know you’re all right and this McElroy fellow hasn’t burned the place to the ground or anything.”

Gloria agreed to call, and agreed to take the Penis-Be-Good stick, too. Becca handed over the keys to her Lincoln Nautilus and the cipher code to get it out of the garage. Gloria tucked the keys and the baton into her purse, gave Becca a quick peck on the lips, then hurried off.

3

The only stressful part of the drive was navigating the cumbersome vehicle through downtown traffic, but once she’d fled the city and was on the open road, she felt cool and collected. She ejected Becca’s Ani DiFranco CD and replaced it with Sviatoslav Richter performing Chopin. She cranked the windows down, and could almost convince herself that she would ultimately arrive at the Hole in the Wall and be provided with some logical excuse why McElroy had been incommunicado for so long. For all she knew, maybe the guy’s cell phone died and he hadn’t noticed because he’d been too preoccupied with work. Ditto, why he’d missed the Zoom meetings with the studio executives. Could be that Davis McElroy was simply in the zone.

Yeah, sure, she thought. She was trying not to let her anger overtake her, because really, that’s what she was feeling—notconcern, not caution for her own well-being, but pure, mounting rage. A part of her hoped the son of a bitch was lying dead of a heart attack in that house, because he’d put her reputation on the line, not to mention a nice chunk of cash if this deal ultimately died on the vine. She could, in fact, excuse a heart attack or stroke—that sort of thing couldn’t be helped—but the selfishness of a relapse? A drug and alcohol binge? That was goddamn inexcusable.

She was reminded again of her former client, George Lee Poach—he of the pasty face, quivering jowls, and damp, eager hands—and of a specific phone call she had received from a perturbed events coordinator a few years ago, informing her that the venerable Mr. Poach was wholly intoxicated and wearing nothing but a tranquil grin as he attempted to order a calzone and a bottle of Knob Creek from the hotel concierge. Gloria didn’t abide such bullshit; she’d dropped Poach as a client immediately after that ordeal. Let Jack Baer juggle the addicts, the booze hounds, the prima donnas; Gloria Grossman did not suffer fools.

Still, Davis McElroy was not George Lee Poach. Yes, she had signed McElroy at the height of his addiction, something she hadn’t realized he’d been suffering from at the time. But after a protracted stint in rehab, he had come out clean and sober and, to the best of Gloria’s knowledge, had remained that way ever since. She’d seen the AA medallions on a small, wall-mounted shelf in his Manhattan apartment, and recalled the uplifting (if somewhat cult-like) mottos he’d occasionally roll out in his languid, professorial voice. Until now, she would have considered Davis McElroy one of her more dependable clients.

She forced herself to quit thinking about it, because her mounting irritation was ruining an otherwise pleasant drive.

4

She relied on the GPS on her phone to lead her to McElroy’s house, although she could have probably found it on her own. It wasn’t that she’d been here often enough to remember the way, it was that there was only a single private road that led up to the house, flanked on either side by what looked like charming little peach trees. The house itself—the Hole in the Wall—materialized at the end of the road, a rustic yet well-maintained two-story cedar cabin with a slate roof dappled with skylights and a cobblestone chimney. It was too sophisticated and modern to be quaint, the updated renovations more on par with Better Homes and Gardens than Guns & Ammo. Davis McElroy had done well for himself, in no small part due to Gloria’s own innate talent for landing a solid deal (in some circles, she was known as the hostage negotiator, a moniker she secretly relished). McElroy’s banana-yellow Triumph Spitfire was in the gravel driveway, and she could see nothing visibly amiss with the house. Not that she had expected to find it burned to the ground, as Becca had suggested, but still.

She parked the Nautilus beside the Spitfire then shut down the engine. Glancing up at the house, framed now in the Nautilus’s polarized windshield, Gloria saw that the blinds on all the windows had been drawn.

She unplugged her cell phone from the portable charger, killed the GPS app, then dialed McElroy’s number. It no longer rang, as it had done all week—only went straight to an automated mailbox that was too full to accept new messages.

Climbing out of the car, she took in a lungful of fresh country air, determined to keep her anger at bay. The air smelled of flowers and tasted clean. We’re all killing ourselves living in that city like a bunch of crazed rats nesting in a dump site, she thought, and not for the first time. Our lungs are probably caustic from taxicab exhaust and we’re all most likely courting a dozen different types of cancer.

She went up the porch steps and knocked on the front door. A semicircular window stood in the door at eye-level, the glass tinted red like the window of a church. Gloria couldn’t get a glimpse inside because the window was covered by an ugly paisley curtain.

A sound then—a high-pitched, motorized rheee! Not from inside the house but from someplace out here.

Please don’t let that be a chainsaw, she thought, somewhat humorlessly. It would have been the exact thing Becca would have said upon hearing it.

The sound died, revved up again, died once more.

“Hey!” she shouted. “Hello? Davis?”

No answer.

She climbed down the steps and walked around to the side of the house. There was a massive oil tank here, red as a fire engine in a child’s storybook, and several large sheets of plywood leaning at an angle against the side of the house. Another couple of steps and she saw an upturned five-gallon bucket and what remained of a fairly large watermelon that looked as if it had been hacked apart by an axe-wielding maniac.

It gave Gloria pause.

Becca’s voice piped up in her head: Worst-case scenario, he’s dead. Or he comes at you swinging a hammer because he’s blotto on smack and thinks you’re Julius Caesar. Funny at the time; not so funny now. And of course Becca’s patented Penis-Be-Good stick was still in her purse, which, in turn, was slumped on the passenger seat of the Nautilus. Fat lot of good it would do her there.

“Davis? Hello? It’s Gloria Grossman. Anybody home?”

Davis McElroy was in his late forties—Gloria’s age—butexuded the youthful good looks of a man at least ten years his junior. Those looks had earned him more than one cameo in a few of the movies he or his friends wrote—once, even a speaking role—and he may have enjoyed a decent run as a second-tier actor had he not been such an introvert. But the man who stepped out from behind the house and into the harsh daylight looked nothing like Davis McElroy. That rugged frat-boy air had vanished, leaving in its place a dark shiftiness, furtive as a wounded animal. He’d lost considerable weight; the open flannel shirt and Race for the Cure T-shirt hung from his wasted frame. His hair had exploded in a dark, unruly mop, bleeding down his face in the form of a spotty, salt-and-pepper beard. His eyes looked haunted.

Davis McElroy froze upon seeing her. He was holding some sort of tool or weapon in his hand, the sight of which did not help ease Gloria’s sudden apprehension.

It’s drugs, all right, she had time to think. Son of a bitch.

“Gloria,” he uttered, and even his voice sounded alien to her. Aggrieved, somehow. He took an unsteady step in her direction, shuffling along like someone unaccustomed to it. His eyes looked like they had strings attached at the back and someone was pulling them deeper into his skull. “Gloria, what the hell are you doing out here?”

“That’s the question I came to ask you, Davis. Where the hell have you been?”

“Where—?” It came out as a croak. He seemed confused. As he managed another step in her direction—

“What have you got in your hand, Davis?”

He blinked, then glanced first down at his empty hand, then at the other one. He raised the item but she still couldn’t make out what it was. Some sort of metal pole or pipe?

“This?” he said. “It’s nothing. It’s a wood chisel.” As if suddenly disgusted by it, he tossed the chisel on the ground.

“Davis, what the hell have you been doing out here? People have been trying to reach you. I’ve been trying to reach you. I drove up from the city to make sure you weren’t dead.”

He said nothing, just seemed to tremble there in front of her like something insubstantial enough to be carried off by a strong gust of wind. He glanced at something toward the rear of the house—something beyond Gloria’s line of sight—thenmet her stare again. Those bleak and anxious eyes appeared to quiver in their sockets.

“What is it, Davis? Cocaine? Pills? Or have you just been at the bottle?”

A vertical crease appeared between his eyebrows. He shook his woolly head. “No, no—it’s nothing like that.”

“You realize you missed your deadline, don’t you?”

“My deadline?”

“The screenplay, Davis. Please tell me you’ve got something to show me.”

“Jesus,” he said, the word wheezing out of him. “Yeah, I know. I mean, I know I missed the deadline. It’s just, time got away from me.”

“You stopped answering your phone. Even John Fish was trying to call you.”

She’d mentioned this to shake him up, maybe drive home just how deep in the shit they were. It had the desired effect, given the expression that overcame his face, but when he opened his mouth, Gloria realized she had miscalculated.

“John Fiiiish.” The name all but seethed out from between McElroy’s teeth. He glanced again at whatever kept attracting his attention behind the house—a tic that was making her increasingly uncomfortable—then scratched nervously at his stubbled neck.

“What have you got back there?” she asked him.

Like a landed trout gasping for air, Davis McElroy’s mouth opened and closed, opened and closed. It made a sickening mawp mawp sound.

“Davis?” she pushed.

“You shouldn’t have come here.” He took another step in her direction—a stagger, really. “It’s not safe. It’s…dangerous.”

She felt herself take an instinctive step back from him. “What’s dangerous?” she asked.

There was a beat of silence. When he spoke, he did so just barely above a whisper, and Gloria couldn’t be certain she heard him correctly. Sounded like he’d said, “The book.”

“I don’t even go in the house anymore, except for when I have to put up a new wall,” he said, then nodded to a small brick structure no bigger than an outhouse farther down the property. “Been sleeping in there. Where it’s safer.”

He took another step in her direction and she took another step back.

“Been eating out here, too,” he continued, and nodded toward the overturned bucket and the decimated watermelon.

“Davis, I think I should call someone and get you help. Would that be okay?”

“Help,” he said, the word sounding like it had come unstuck from the roof of his mouth. “Help would be nice.”

To Gloria’s horror, he collapsed to a seated position in the grass and began to weep.

Every instinct told her to bolt back to the car and get the hell out of there. She could call the goddamn cops from the highway, have them come and collect the son of a bitch. But she didn’t do that. She was on the hook now, her curiosity about what Davis kept glancing at behind the house besting any impulse of survival. Besides, she couldn’t leave here without the screenplay.

She stepped around him, one cork-heeled sandal brushing the watermelon rind and setting it rocking. It was a pleasant day on its way toward a cool and clear evening. The air had been scented with lilac just moments ago, but as she turned the corner of the house and crossed into the back yard, she caught a whiff of sawdust and overheated electrical equipment.

There was a flagstone patio back here that led to a set of double doors at the rear of the house. These doors both stood wide open now, and there was some sort of construction project erected on the patio in front of them: a pair of sawhorses hoisting one of those sheets of plywood, a scattering of two-by-fours lying on a bedding of sawdust, a circular saw that must have accounted for the mechanical whine she had heard from the front porch.

She looked down, saw her shoe had gotten tangled around a loop of orange electrical cord, and shook it loose.

There was something inside the house, just beyond those wide-open double doors. That would be the parlor, she recalled, a den with exposed wooden beams in the ceiling and a cobblestone fireplace to match the chimney. When she and Becca had been here last—a year ago?—McElroy had taken to outfitting the entire room in a garish Navajo motif that didn’t quite jibe with the rest of the house’s modern design. McElroy, clutching a rocks glass of spring water with a twist of lime, had laughed at Gloria’s expression as she’d run a hand along the woven Native American blanket folded over the back of his Naugahyde sofa. Yeah, I know, the place looks like a ski lodge, McElroy had said. I never did have a sense for fashion, but I like what I like.

She stepped over piles of sawdust and a scattering of bent, discarded carpentry nails, and approached the open doorway.

What looked like an enormous wooden crate stood in the center of the room. In fact, it occupied the majority of the room, its top nearly butting against the exposed ceiling beams, its width expansive enough to run flush with the fireplace mantel. The Naugahyde sofa was still here, but the crate had shoved it against one wall, its cushions torn and its frame cracked. The enormity of the thing—the inexplicable nature of what she was looking at—gave her a momentary flutter of vertigo.

Whatever the crate was, whatever purpose it served, Davis McElroy had built it. She’d witnessed people do some crazy things while on drugs, but something about this troubled her on some deeper, inexplicable level.

“I know how this looks,” he said, startling her. He’d gotten himself under control, though his face was now mottled in red splotches from crying. He wavered there in the doorway like something insubstantial—like she might reach for him only to have her hand pass unimpeded through his body, ghostlike.

Gloria turned away from him. She didn’t like looking at his eyes. It was like someone else staring out from behind the mask of his face.

“What is all this, Davis?”

“Pandora’s Box,” he said, looking past her and into the house. At the crate he’d built. “Despite the old adage, I guess you could say I’m trying to close it back up.”

A terrible notion occurred to her. “Is there something inthere?” But she wasn’t thinking something, she was thinking someone.

“Christ, yes,” he said. His voice sounded raw and exhausted. “I mean, it should…I hope it’s…” He trailed off.

She stepped into the room, could smell the cut wood, could see the pixie-like filaments of sawdust spiraling lazily in a shaft of fading sunlight. Because the crate was so tall, it looked like McElroy had amputated the chandelier from its housing in the ceiling; an eye socket that drooled out lengths of wire was all she could see up there.

She stood on her toes and touched the top surface of the crate. Felt the nail-heads poking up from the wood, the splinters jutting from the two-by-four brace. She looked to her left and saw an antique end table smashed to kindling. There was the chandelier, too—a hideous artifact comprised of antlers—casually discarded on the floor in the hallway. She squeezed past the crate and leaned into the hall, caught a whiff of shit and spoiled food. No scent of booze, and no evidence of empty bottles anywhere. She withdrew back into the parlor.

“Explain this to me,” she said.

Davis McElroy gazed at the massive crate. One of his eyelids twitched. He looked apprehensive, like he suddenly didn’t want to be too close to it.

“I guess you could say I’ve trapped it,” he said. “Like a wild animal.”

“Trapped what?”

“The book,” he said.

“What book?”

A humorless chuckle burped out of him. “His book. John Fish.”

“The Skin of Her—”

“Don’t say it!” he shouted, holding his hands up in a warding off posture.

Gloria flinched, as if he might strike her.

“Don’t say it. Don’t say it. It’ll hear you.”

“The…book? The book will hear me?”

“You,” he said. “Me. Everyone. Anyone.” He lowered his voice and said, “It listens.”

She pointed at the crate. “The book is in there?”

“It should be. I hope so. It was at one time. I haven’t seen any new holes. Only…”

“Only what?”

“Only it’s been chewing its way out. So I have to keep building walls around it so that it doesn’t chew its way out and get free.”

“Excuse me,” she said. She pushed past him and went back out onto the patio.

McElroy lingered inside a moment longer, then followed her outside. He winced when the sun struck his face. Turning his head, the sunlight reflected off his beard, causing one half of his face to shimmer like gold.

“I’m not crazy and I’m not on drugs. You don’t know what it’s been like out here, Gloria. The things that have happened…”

“Tell me,” she said.

He coughed almost demurely into a fist, then said, “It started soon after I’d begun writing the screenplay. Little things at first, the way a haunting in a movie will start small then gradually ramp up momentum. The book—at first, it would disappear. Or…no, not disappear. Relocate. Like something alive, moving about the house. I’d find it in some other room, under a bed, in a kitchen cabinet with the coffee mugs. In the bathtub. I thought I was losing my mind—like,was I relocating the book to all these random places only to have no recollection of doing so? Were those memories wiped clean from my mind?”

There was another upturned five-gallon bucket back here in the grass. Gloria went to it and dropped herself down onto it. There used to be a wooden bench back here, she recalled. She looked out over the yard, naked and barren except for the unkempt grass, straight out to the swell of woods at the horizon. The yard used to be dotted with bird feeders, too, she remembered. At least a dozen of them. Those were all gone now, too.

She was beginning to feel lightheaded.

“But that wasn’t it,” McElroy continued. “I realize that now. At first, you see, it was trying to get away. Fight or flight. It opted to flee. To escape. I didn’t know it then, but that’s exactly what it was doing. Was trying to do.”

“The book,” she said, just to make sure she was actually following this bizarre story.

“Yes. The book.” He ran a shaky hand through his mop of hair, then giggled like a child. “My God, Gloria, do you realize? If I’d only understood what it was trying to do back then, I would have let it go. Can you imagine? Can you imagine how differently things would have turned out? I mean, if I’d realized what it was trying to do back then, I would have just let it go. But I didn’t know. And then things got worse.”

“Worse how?” she asked, though she was not so sure she actually wanted to know.

“It fucking bit me,” McElroy said, tugging up the sleeve of his flannel shirt. The wound in his arm looked less like a bite and more like someone had slashed him repeatedly with a blade.

“Jesus, Davis,” she said, horrified. Had he done that to himself?

“Yeah, I know.” He fingered one of the slashes, now a crusty brownish scab. “Doesn’t really hurt. Not now. Just…justfreaked me out more than anything, you know?”

“How did a book do that to you?”

Again, he chuckled—a nervous titter. “I know, right? But Gloria, it came at me. Hungry. Pissed off. I don’t know. More than once, too.”

He bent and cuffed up one leg of his filthy carpenter’s pants with both hands. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...