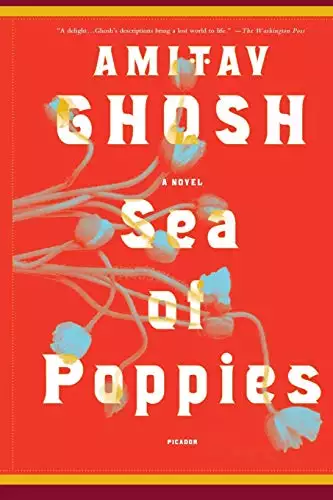

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

At the heart of this vibrant saga is an immense ship, the Ibis. Its destiny is a tumultuous voyage across the Indian Ocean, its purpose to fight China's vicious nineteenth-century Opium Wars. As for the crew, they are a motley array of sailors and stowaways, coolies and convicts.

In a time of colonial upheaval, fate has thrown together a diverse cast of Indians and Westerners, from a bankrupt Raja to a widowed tribeswoman, from a mulatto American freedman to a free-spirited French orphan. As their old family ties are washed away, they, like their historical counterparts, come to view themselves as jahaj-bhais, or ship brothers. An unlikely dynasty is born, which will span continents, races, and generations.

The vast sweep of this historical adventure embraces the lush poppy fields of the Ganges, the rolling high seas, and the crowded backstreets of Canton. But it is the panorama of characters, whose diaspora encapsulates the vexed colonial history of the East itself, that makes Sea of Poppies so breathtakingly alive - a masterpiece from one of the world's finest novelists.

"Such is the power of Ghosh's precise, understated prose that one occasionally wishes to turn the pages three at a time, eager to find out where Ghosh's tale is headed." - The Boston Globe

Release date: September 29, 2009

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Print pages: 528

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sea of Poppies

Amitav Ghosh

The vision of a tall-masted ship, at sail on the ocean, came to Deeti on an otherwise ordinary day, but she knew instantly that the apparition was a sign of destiny, for she had never seen such a vessel before, not even in a dream: how could she have, living as she did in northern Bihar, four hundred miles from the coast? Her village was so far inland that the sea seemed as distant as the netherworld: it was the chasm of darkness where the holy Ganga disappeared into the Kala-Pani, 'the Black Water'.

It happened at the end of winter, in a year when the poppies were strangely slow to shed their petals: for mile after mile, from Benares onwards, the Ganga seemed to be flowing between twin glaciers, both its banks being blanketed by thick drifts of white-petalled flowers. It was as if the snows of the high Himalayas had descended on the plains to await the arrival of Holi and its springtime profusion of colour.

The village in which Deeti lived was on the outskirts of the town of Ghazipur, some fifty miles east of Benares. Like all her neighbours, Deeti was preoccupied with the lateness of her poppy crop: that day, she rose early and went through the motions of her daily routine, laying out a freshly washed dhoti and kameez for Hukam Singh, her husband, and preparing the rotis and achar he would eat at midday. Once his meal had been wrapped and packed, she broke off to pay a quick visit to her shrine room: later, after she'd bathed and changed, Deeti would do a proper puja, with flowers and offerings; now, being clothed still in her night-time sari, she merely stopped at the door, to join her hands in a brief genuflection.

Soon a squeaking wheel announced the arrival of the ox-cart that would take Hukam Singh to the factory where he worked, in Ghazipur, three miles away. Although not far, the distance was too great for Hukam Singh to cover on foot, for he had been wounded in the leg while serving as a sepoy in a British regiment. The disability was not so severe as to require crutches, however, and Hukam Singh was able to make his way to the cart without assistance. Deeti followed a step behind, carrying his food and water, handing the cloth-wrapped package to him after he had climbed in.

Kalua, the driver of the ox-cart, was a giant of a man, but he made no move to help his passenger and was careful to keep his face hidden from him: he was of the leather-workers' caste and Hukam Singh, as a high-caste Rajput, believed that the sight of his face would bode ill for the day ahead. Now, on climbing into the back of the cart, the former sepoy sat facing to the rear, with his bundle balanced on his lap, to prevent its coming into direct contact with any of the driver's belongings. Thus they would sit, driver and passenger, as the cart creaked along the road to Ghazipur - conversing amicably enough, but never exchanging glances.

Deeti, too, was careful to keep her face covered in the driver's presence: it was only when she went back inside, to wake Kabutri, her six-year-old daughter, that she allowed the ghungta of her sari to slip off her head. Kabutri was lying curled on her mat and Deeti knew, because of her quickly changing pouts and smiles, that she was deep in a dream: she was about to rouse her when she stopped her hand and stepped back. In her daughter's sleeping face, she could see the lineaments of her own likeness - the same full lips, rounded nose and upturned chin - except that in the child the lines were still clean and sharply drawn, whereas in herself they had grown smudged and indistinct. After seven years of marriage, Deeti was not much more than a child herself, but a few tendrils of white had already appeared in her thick black hair. The skin of her face, parched and darkened by the sun, had begun to flake and crack around the corners of her mouth and her eyes. Yet, despite the careworn commonplaceness of her appearance, there was one respect in which she stood out from the ordinary: she had light grey eyes, a feature that was unusual in that part of the country. Such was the colour - or perhaps colourlessness - of her eyes that they made her seem at once blind and all-seeing. This had the effect of unnerving the young, and of reinforcing their prejudices and superstitions to the point where they would sometimes shout taunts at her - chudaliya, dainiya - as if she were a witch: but Deeti had only to turn her eyes on them to make them scatter and run off. Although not above taking a little pleasure in her powers of discomfiture, Deeti was glad, for her daughter's sake, that this was one aspect of her appearance that she had not passed on - she delighted in Kabutri's dark eyes, which were as black as her shiny hair. Now, looking down on her daughter's dreaming face, Deeti smiled and decided that she wouldn't wake her after all: in three or four years the girl would be married and gone; there would be enough time for her to work when she was received into her husband's house; in her few remaining years at home she might as well rest.

With scarcely a pause for a mouthful of roti, Deeti stepped outside, on to the flat threshold of beaten earth that divided the mud-walled dwelling from the poppy fields beyond. By the light of the newly risen sun, she saw, greatly to her relief, that some of her flowers had at last begun to shed their petals. On the adjacent field, her husband's younger brother, Chandan Singh, was already out with his eight-bladed nukha in hand. He was using the tool's tiny teeth to make notches on some of the bare pods - if the sap flowed freely overnight he would bring his family out tomorrow, to tap the field. The timing had to be exactly right because the priceless sap flowed only for a brief period in the plant's span of life: a day or two this way or that, and the pods were of no more value than the blossoms of a weed.

Chandan Singh had seen her too and he was not a person who could let anyone pass by in silence. A slack-jawed youth with a brood of five children of his own, he never missed an opportunity to remind Deeti of her paucity of offspring. Ka bhaíl? he called out, licking a drop of fresh sap from the tip of his instrument. What's the matter? Working alone again? How long can you carry on like this? You need a son, to give you a helping hand. You're not barren, after all . . .

Being accustomed to her brother-in-law's ways, Deeti had no difficulty in ignoring his jibes: turning her back on him, she headed into her own field, carrying a wide wicker basket at her waist. Between the rows of flowers, the ground was carpeted in papery petals and she scooped them up in handfuls, dropping them into her basket. A week or two before, she would have taken care to creep sideways, so as not to disturb the flowers, but today she all but flounced as she went and was none too sorry when her swishing sari swept clusters of petals off the ripening pods. When the basket was full, she carried it back and emptied it next to the outdoor chula where she did most of her cooking. This part of the threshold was shaded by two enormous mango trees, which had just begun to sprout the dimples that would grow into the first buds of spring. Relieved to be out of the sun, Deeti squatted beside her oven and thrust an armload of firewood into last night's embers, which could still be seen glowing, deep inside the ashes.

Kabutri was awake now, and when she showed her face in the doorway, her mother was no longer in a mood to be indulgent. So late? she snapped. Where were you? Kám-o-káj na hoi? You think there's no work to be done?

Deeti gave her daughter the job of sweeping the poppy petals into a heap while she busied herself in stoking the fire and heating a heavy iron tawa. Once this griddle was heated through, she sprinkled a handful of petals on it and pressed them down with a bundled-up rag. Darkening as they toasted, the petals began to cling together so that in a minute or two they looked exactly like the round wheat-flour rotis Deeti had packed for her husband's midday meal. And 'roti' was indeed the name by which these poppy-petal wrappers were known although their purpose was entirely different from that of their namesake: they were to be sold to the Sudder Opium Factory, in Ghazipur, where they would be used to line the earthenware containers in which opium was packed.

Kabutri, in the meanwhile, had kneaded some atta and rolled out a few real rotis. Deeti cooked them quickly, before poking out the fire: the rotis were put aside, to be eaten later with yesterday's leftovers - a dish of stale alu-posth, potatoes cooked in poppy-seed paste. Now, her mind turned to her shrine room again: with the hour of the noontime puja drawing close, it was time to go down to the river for a bath. After massaging poppy-seed oil into Kabutri's hair and her own, Deeti draped her spare sari over her shoulder and led her daughter towards the water, across the field.

The poppies ended at a sandbank that sloped gently down to the Ganga; warmed by the sun, the sand was hot enough to sting the soles of their bare feet. The burden of motherly decorum slipped suddenly off Deeti's bowed shoulders and she began to run after her daughter, who had skipped on ahead. A pace or two from the water's edge, they shouted an invocation to the river - Jai Ganga Mayya ki . . . - and gulped down a draught of air, before throwing themselves in.

They were both laughing when they came up again: it was the time of year when, after the initial shock of contact, the water soon reveals itself to be refreshingly cool. Although the full heat of summer was still several weeks away, the flow of the Ganga had already begun to dwindle. Turning in the direction of Benares, in the west, Deeti hoisted her daughter aloft, to pour out a handful of water as a tribute to the holy city. Along with the offering, a leaf flowed out of the child's cupped palms. They turned to watch as the river carried it downstream towards the ghats of Ghazipur.

The walls of Ghazipur's opium factory were partially obscured by mango and jackfruit trees but the British flag that flew on top of it was just visible above the foliage, as was the steeple of the church in which the factory's overseers prayed. At the factory's ghat on the Ganga, a one-masted pateli barge could be seen, flying the pennant of the English East India Company. It had brought in a shipment of chalán opium, from one of the Company's outlying sub-agencies, and was being unloaded by a long line of coolies.

Ma, said Kabutri, looking up at her mother, where is that boat going?

It was Kabutri's question that triggered Deeti's vision: her eyes suddenly conjured up a picture of an immense ship with two tall masts. Suspended from the masts were great sails of a dazzling shade of white. The prow of the ship tapered into a figurehead with a long bill, like a stork or a heron. There was a man in the background, standing near the bow, and although she could not see him clearly, she had a sense of a distinctive and unfamiliar presence.

Deeti knew that the vision was not materially present in front of her - as, for example, was the barge moored near the factory. She had never seen the sea, never left the district, never spoken any language but her native Bhojpuri, yet not for a moment did she doubt that the ship existed somewhere and was heading in her direction. The knowledge of this terrified her, for she had never set eyes on anything that remotely resembled this apparition, and had no idea what it might portend.

Kabutri knew that something unusual had happened, for she waited a minute or two before asking: Ma? What are you looking at? What have you seen?

Deeti's face was a mask of fear and foreboding as she said, in a shaky voice: Beti - I saw a jahaj - a ship.

Do you mean that boat over there?

No, beti: it was a ship like I've never seen before. It was like a great bird, with sails like wings and a long beak.

Casting a glance downriver, Kabutri said: Can you draw for me what you saw?

Deeti answered with a nod and they waded ashore. They changed quickly and filled a pitcher with water from the Ganga, for the puja room. When they were back at home, Deeti lit a lamp before leading Kabutri into the shrine. The room was dark, with soot-blackened walls, and it smelled strongly of oil and incense. There was a small altar inside, with statues of Shivji and Bhagwan Ganesh, and framed prints of Ma Durga and Shri Krishna. But the room was a shrine not just to the gods but also to Deeti's personal pantheon, and it contained many tokens of her family and forebears - among them such relics as her dead father's wooden clogs, a necklace of rudraksha beads left to her by her mother, and faded imprints of her grandparents' feet, taken on their funeral pyres. The walls around the altar were devoted to pictures that Deeti had drawn herself, in outline, on papery poppy-petal discs: such were the charcoal portraits of two brothers and a sister, all of whom had died as children. A few living relatives were represented too, but only by diagrammatic images drawn on mango leaves - Deeti believed it to be bad luck to attempt overly realistic portraits of those who had yet to leave this earth. Thus her beloved older brother, Kesri Singh, was depicted by a few strokes that stood for his sepoy's rifle and his upturned moustache.

Now, on entering her puja room, Deeti picked up a green mango leaf, dipped a fingertip in a container of bright red sindoor and drew, with a few strokes, two wing-like triangles hanging suspended above a long curved shape that ended in a hooked bill. It could have been a bird in flight but Kabutri recognized it at once for what it was - an image of a two-masted vessel with unfurled sails. She was amazed that her mother had drawn the image as though she were representing a living being.

Are you going to put it in the puja room? she asked.

Yes, said Deeti.

The child could not understand why a ship should find a place in the family pantheon. But why? she said.

I don't know, said Deeti, for she too was puzzled by the sureness of her intuition: I just know that it must be there; and not just the ship, but also many of those who are in it; they too must be on the walls of our puja room.

But who are they? said the puzzled child.

I don't know yet, Deeti told her. But I will when I see them.

The carved head of a bird that held up the bowsprit of the Ibis was unusual enough to serve as proof, to those who needed it, that this was indeed the ship that Deeti saw while standing half-immersed in the waters of the Ganga. Later, even seasoned sailors would admit that her drawing was an uncannily evocative rendition of its subject, especially considering that it was made by someone who had never set eyes on a two-masted schooner - or, for that matter, any other deep-water vessel.

In time, among the legions who came to regard the Ibis as their ancestor, it was accepted that it was the river itself that had granted Deeti the vision: that the image of the Ibis had been transported upstream, like an electric current, the moment the vessel made contact with the sacred waters. This would mean that it happened in the second week of March 1838, for that was when the Ibis dropped anchor off Ganga-Sagar Island, where the holy river debouches into the Bay of Bengal. It was here, while the Ibis waited to take on a pilot to guide her to Calcutta, that Zachary Reid had his first look at India: what he saw was a dense thicket of mangroves, and a mudbank that appeared to be uninhabited until it disgorged its bumboats - a small flotilla of dinghies and canoes, all intent on peddling fruit, fish and vegetables to the newly arrived sailors.

Zachary Reid was of medium height and sturdy build, with skin the colour of old ivory and a mass of curly, lacquer-black hair that tumbled over his forehead and into his eyes. The pupils of his eyes were as dark as his hair, except that they were flecked with sparks of hazel: as a child, strangers were apt to say that a pair of twinklers like his could be sold as diamonds to a duchess (later, when it came time for him to be included in Deeti's shrine, much would be made of the brilliance of his gaze). Because he laughed easily and carried himself with a carefree lightness, people sometimes took him to be younger than he was, but Zachary was always quick to offer a correction: the son of a Maryland freedwoman, he took no small pride in the fact of knowing his precise age and the exact date of his birth. To those in error, he would point out that he was twenty, not a day less and not many more.

It was Zachary's habit to think, every day, of at least five things to praise, a practice that had been instilled by his mother as a necessary corrective for a tongue that sometimes sported too sharp an edge. Since his departure from America it was the Ibis herself that had figured most often in Zachary's daily tally of praiseworthy things. It was not that she was especially sleek or rakish in appearance: on the contrary, the Ibis was a schooner of old-fashioned appearance, neither lean, nor flush-decked like the clippers for which Baltimore was famous. She had a short quarter-deck, a risen fo'c'sle, with a fo'c'sle-deck between the bows, and a deckhouse amidships, that served as a galley and cabin for the bo'suns and stewards. With her cluttered main deck and her broad beam, the Ibis was sometimes taken for a schooner-rigged barque by old sailors: whether there was any truth to this Zachary did not know, but he never thought of her as anything other than the topsail schooner that she was when he first signed on to her crew. To his eye there was something unusually graceful about the Ibis's yacht-like rigging, with her sails aligned along her length rather than across the line of her hull. He could see why, with her main- and headsails standing fair, she might put someone in mind of a white-winged bird in flight: other tall-masted ships, with their stacked loads of square canvas, seemed almost ungainly in comparison.

One thing Zachary did know about the Ibis was that she had been built to serve as a 'blackbirder', for transporting slaves. This, indeed, was the reason why she had changed hands: in the years since the formal abolition of the slave trade, British and American naval vessels had taken to patrolling the West African coast in growing numbers, and the Ibis was not swift enough to be confident of outrunning them. As with many another slave-ship, the schooner's new owner had acquired her with an eye to fitting her for a different trade: the export of opium. In this instance the purchasers were a firm called Burnham Bros., a shipping company and trading house that had extensive interests in India and China.

The new owners' representatives had lost no time in calling for the schooner to be dispatched to Calcutta, which was where the head of the house, Benjamin Brightwell Burnham, had his principal residence: the Ibis was to be refitted upon reaching her destination, and it was for this purpose that Zachary had been taken on. Zachary had spent eight years working in the Gardiner shipyard, at Fell's Point in Baltimore, and he was eminently well-qualified to supervise the outfitting of the old slave-ship: but as for sailing, he had no more knowledge of ships than any other shore-bound carpenter, this being his first time at sea. But Zachary had signed on with a mind to learning the sailor's trade, and he stepped on board with great eagerness, carrying a canvas ditty-bag that held little more than a change of clothes and a penny-whistle that his father had given him as a boy. The Ibis provided him with a quick, if stern schooling, the log of her voyage being a litany of troubles almost from the start. Mr Burnham was in such a hurry to get his new schooner to India that she had sailed short-handed from Baltimore, shipping a crew of nineteen, of whom nine were listed as 'Black', including Zachary. Despite being undermanned, her provisions were deficient, both in quality and quantity, and this had led to confrontations, between stewards and sailors, mates and fo'c'slemen. Then she hit heavy seas and her timbers were found to be weeping: it fell to Zachary to discover that the 'tween-deck, where the schooner's human cargo had been accommodated, was riddled with peepholes and air ducts, bored by generations of captive Africans. The Ibis was carrying a cargo of cotton, to defray the costs of the journey; after the inundation, the bales were drenched and had to be jettisoned.

Off the coast of Patagonia, foul weather forced a change in course, which had been plotted to take the Ibis across the Pacific and around Java Head. Instead, her sails were set for the Cape of Good Hope - with the result that she ran afoul of the weather again, and was becalmed a fortnight in the doldrums. With the crew on half-rations, eating maggoty hardtack and rotten beef, there was an outbreak of dysentery: before the wind picked up again, three men were dead and two of the black crewmen were in chains, for refusing the food that was put before them. With hands running short, Zachary had put aside his carpenter's tools and become a fully fledged foretopman, running up the ratlines to bend the topsail.

Then it happened that the second mate, who was a hard-horse, hated by every black man in the crew, fell overboard and drowned: everyone knew the fall to be no accident, but the tensions on the vessel had reached such a point that the ship's master, a sharp-tongued Boston Irishman, let the matter slip. Zachary was the only member of the crew to put in a bid when the dead man's effects were auctioned, thus coming into possession of a sextant and a trunk-load of clothes.

Soon, being neither of the quarter-deck nor of the fo'c'sle, Zachary became the link between the two parts of the ship, and was shouldering the duties of the second mate. He was not quite the novice now that he had been at the start of the voyage, but nor was he equal to his new responsibilities. His faltering efforts did nothing to improve morale and when the schooner put in to Cape Town the crew melted away overnight, to spread word of a hell-afloat with pinch-gut pay. The reputation of the Ibis was so damaged that not a single American or European, not even the worst rufflers and rum-gaggers, could be induced to sign on: the only seamen who would venture on her decks were lascars.

This was Zachary's first experience of this species of sailor. He had thought that lascars were a tribe or nation, like the Cherokee or Sioux: he discovered now that they came from places that were far apart, and had nothing in common, except the Indian Ocean; among them were Chinese and East Africans, Arabs and Malays, Bengalis and Goans, Tamils and Arakanese. They came in groups of ten or fifteen, each with a leader who spoke on their behalf. To break up these groups was impossible; they had to be taken together or not at all, and although they came cheap, they had their own ideas of how much work they would do and how many men would share each job - which seemed to mean that three or four lascars had to be hired for jobs that could well be done by a single able seaman. The Captain declared them to be as lazy a bunch of niggers as he had ever seen, but to Zachary they appeared more ridiculous than anything else. Their costumes, to begin with: their feet were as naked as the day they were born, and many seemed to own no clothing other than a length of cambric to wind around their middle. Some paraded around in drawstringed knickers, while others wore sarongs that flapped around their scrawny legs like petticoats, so that at times the deck looked like the parlour of a honeyhouse. How could a man climb a mast in bare feet, swaddled in a length of cloth, like a newborn child? No matter that they were as nimble as any seaman he'd ever seen - it still discomfited Zachary to see them in the rigging, hanging like monkeys on the ratlines: when their sarongs blew in the wind, he would avert his eyes for fear of what he might see if he looked up.

After several changes of mind, the skipper decided to engage a lascar company that was led by one Serang Ali. This was a personage of formidable appearance, with a face that would have earned the envy of Genghis Khan, being thin, long and narrow, with darting black eyes that sat restlessly upon rakishly angled cheekbones. Two feathery strands of moustache drooped down to his chin, framing a mouth that was constantly in motion, its edges stained a bright, livid red: it was as if he were forever smacking his lips after drinking from the opened veins of a mare, like some bloodthirsty Tartar of the steppes. The discovery that the substance in his mouth was of vegetable origin came as no great reassurance to Zachary: once, when the serang spat a stream of blood-red juice over the rail, he noticed the water below coming alive with the thrashing of shark's fins. How harmless could this betel-stuff be if it could be mistaken for blood by a shark?

The prospect of journeying to India with this crew was so unappealing that the first mate disappeared too, taking himself off the ship in such a hurry that he left behind a bagful of clothes. When told that the mate was a gone-goose, the skipper growled: 'Cut his painter, has he? Don't blame him neither. I'd of walked my chalks too, if I'd'a been paid.'

The Ibis's next port of call was to be the island of Mauritius, where they were to exchange a cargo of grain for a load of ebony and hardwood. Since no other sea-officer could be found before their departure, the schooner sailed with Zachary standing in for the first mate: thus it happened that in the course of a single voyage, by virtue of desertions and dead-tickets, he vaulted from the merest novice sailor to senior seaman, from carpenter to second-in-command, with a cabin of his own. His one regret about the move from fo'c'sle to cabin was that his beloved penny-whistle disappeared somewhere on the way and had to be given up for lost.

Before this, the skipper had instructed Zachary to eat his meals below - 'not going to spill no colour on my table, even if it's just a pale shade of yaller.' But now, rather than dine alone, he insisted on having Zachary share the table in the cuddy, where they were waited on by a sizeable contingent of lascar ship's-boys - a scuttling company of launders and chuckeroos.

Once under sail, Zachary was forced to undergo yet another education, not so much in seamanship this time, as in the ways of the new crew. Instead of the usual sailors' games of cards and able-whackets, there was the clicking of dice, with games of parcheesi unfolding on chequerboards of rope; the cheerful sound of sea-shanties yielded to tunes of a new kind, wild and discordant, and the very smell of the ship began to change, with the odour of spices creeping through the timbers. Having been put in charge of the ship's stores Zachary had to familiarize himself with a new set of provisions, bearing no resemblance to the accustomed hardtack and brined beef; he had to learn to say 'resum' instead of 'rations', and he had to wrap his tongue around words like 'dal', 'masala' and 'achar'. He had to get used to 'malum' instead of mate, 'serang' for bosun, 'tindal' for bosun's mate, and 'seacunny' for helmsman; he had to memorize a new shipboard vocabulary, which sounded a bit like English and yet not: the rigging became the 'ringeen', 'avast!' was 'bas!', and the cry of the middle-morning watch went from 'all's well' to 'alzbel'. The deck now became the 'tootuk' while the masts were 'dols'; a command became a 'hookum' and instead of starboard and larboard, fore and aft, he had to say 'jamna' and 'dawa', 'agil' and 'peechil'.

One thing that continued unchanged was the division of the crew into two watches, each led by a tindal. Most of the business of the ship fell to the two tindals, and little was seen of Serang Ali for the first two days. But on the third, Zachary came on deck at dawn to be greeted with a cheerful: 'Chin-chin Malum Zikri! You catchi chow-chow? Wat dam t'ing hab got inside?'

Although startled at first, Zachary soon found himself speaking to the serang with an unaccustomed ease: it was as if his oddly patterned speech had unloosed his own tongue. 'Serang Ali, where you from?' he asked.

'Serang Ali blongi Rohingya - from Arakan-side.'

'And where'd you learn that kinda talk?'

'Afeem ship,' came the answer. 'China-side, Yankee gen'l'um allo tim tok so-fashion. Also Mich'man like Malum Zikri.'

'I ain no midshipman,' Zachary corrected him. 'Signed on as the ship's carpenter.'

'Nevva mind,' said the serang, in an indulgent, paternal way. 'Nevva mind: allo same-sem. Malum Zikri sun-sun become pukka gen'l'um. So tell no: catchi wife-o yet?'

'No.' Zachary laughed. ''N'how bout you? Serang Ali catchi wife?'

'Serang Ali wife-o hab makee die,' came the answer. 'Go topside, to hebbin. By'mby, Serang Ali catchi nother piece wife . . .'

A week later, Serang Ali accosted Zachary again: 'Malum Zikri! Captin-bugger blongi poo-shoo-foo. He hab got plenty sick! Need one piece dokto. No can chow-chow tiffin. Allo tim do chheechhee, pee-pee. Plenty smelly in Captin cabin.'

Zachary took himself off to the Captain's stateroom and was told that there was nothing wrong: just a touch of the back-door trots - not the flux, for there was no sign of blood, no spotting in the mustard. 'I know how to take care o' meself: not the first time I've had a run of the squitters and collywobbles.'

But soon the skipper was too weak to leave his cabin and Zachary was handed charge of the ship's log and the navigation charts. Having been schooled until the age of twelve, Zachary was able to write a slow but well-formed copperplate hand

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...