- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

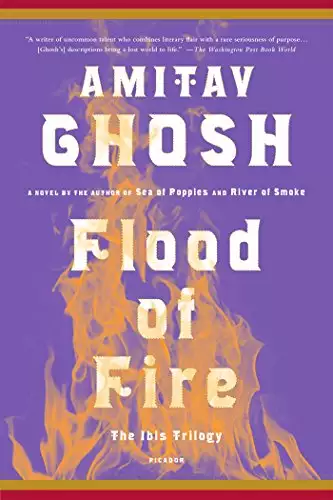

The stunningly vibrant final novel in the bestselling Ibis Trilogy

It is 1839 and China has embargoed the trade of opium, yet too much is at stake in the lucrative business and the British Foreign Secretary has ordered the colonial government in India to assemble an expeditionary force for an attack to reinstate the trade. Among those consigned is Kesri Singh, a soldier in the army of the East India Company. He makes his way eastward on the Hind, a transport ship that will carry him from Bengal to Hong Kong.

Along the way, many characters from the Ibis Trilogy come aboard, including Zachary Reid, a young American speculator in opium futures, and Shireen, the widow of an opium merchant whose mysterious death in China has compelled her to seek out his lost son. The Hind docks in Hong Kong just as war breaks out and opium "pours into the market like monsoon flood." From Bombay to Calcutta, from naval engagements to the decks of a hospital ship, among embezzlement, profiteering, and espionage, Amitav Ghosh charts a breathless course through the culminating moment of the British opium trade and vexed colonial history.

With all the verve of the first two novels in the trilogy, Flood of Fire completes Ghosh's unprecedented reenvisioning of the nineteenth-century war on drugs. With remarkable historic vision and a vibrant cast of characters, Ghosh brings the Opium Wars to bear on the contemporary moment with the storytelling that has charmed readers around the world.

Release date: August 2, 2016

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Print pages: 624

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Flood of Fire

Amitav Ghosh

Havildar Kesri Singh was the kind of soldier who liked to take the lead, particularly on days like this one, when his battalion was marching through a territory that had already been subdued and the advance-guard's job was only to fly the paltan's colours and put on their best parade-faces for the benefit of the crowds that had gathered by the roadside.

The villagers who lined the way were simple people and Kesri didn't need to look into their eyes to know that they were staring at him in wide-eyed wonder. East India Company sepoys were an unusual sight in this remote part of Assam: to have a full paltan of the Bengal Native Infantry's 25th Regiment - the famous 'Pacheesi' - marching through the rice-fields was probably as great a tamasha as most of them would witness in a year, or even a decade.

Kesri had only to look ahead to see dozens of people flocking to the roadside: farmers, old women, cowherds, children. They were racing up to watch, as if fearful of missing the show: little did they know that the spectacle would continue for hours yet.

Right behind Kesri's horse, following on foot, was the so-called Russud Guard - the 'foraging party'. Behind them were the camp-followers - inaccurately named, since they actually marched ahead of the troops and far exceeded them in number, there being more than two thousand of them to a mere six hundred sepoys. Their caravan was like a moving city, a long train of ox-drawn bylees carrying people of all sorts - pandits and milk-women, shopkeepers and banjara grain-sellers, even a troupe of bazar-girls. Animals too there were aplenty - noisy flocks of sheep, goats and bullocks, and a couple of elephants as well, carrying the officers' baggage and the furniture for their mess, the tables and chairs tied on with their legs in the air, wriggling and shaking like upended beetles. There was even a travelling temple, trundling along atop a cart.

Only after all of this had passed would a rhythmic drumbeat make itself heard and a cloud of dust appear. The ground would reverberate, in time with the beat, as the first rank of sepoys came into view, ten abreast, at the head of a long, winding river of dark topees and flashing bayonets. The sight would send the villagers scurrying for cover; they would watch from the shelter of trees and bushes while the sepoys marched by, piped along by fifers and drummers.

Few were the tamashas that could compare with the spectacle of the Bengal Native Infantry on the march. Every member of the paltan was aware of this - dandia-wallahs, naach-girls, bangy-burdars, syces, mess-consummers, berry-wallahs, bhisties - but none more so than Havildar Kesri Singh, whose face served as the battalion's figurehead when he rode at the head of the column.

It was Kesri's belief that to put on a good show was a part of soldiering and it caused him no shame to admit that it was principally because of his looks that he was so often chosen to lead the march. He could hardly be held to blame if his years of campaigning had earned him a patchwork of scars to improve his appearance - it was not as if he had asked to be grazed by a sword in such a way as to add a pout to his lower lip; nor had he invited the cut that was etched upon the leather-dark skin of his cheek, like a finely drawn tattoo.

But it wasn't as if Kesri's was the most imposing face in the paltan. He could certainly look forbidding enough when he wanted to, with his scimitar-like moustaches and heavy brow, but there were others who far surpassed him in this regard. It was in his manner of wearing the regimental uniform that he yielded to none: the heft of his thighs was such that the black fabric of his trowsers hugged them like a second skin, outlining his musculature; his chest was wide enough that the 'wings' on his shoulders looked like weapons rather than ornaments; and there wasn't a man in the paltan on whom the scarlet coattee, with its bright yellow facings, showed to better advantage. As for the dark topee, tall as a beehive, he was not alone in thinking that it sat better on his head than on any other.

Kesri knew that it was a matter of some resentment among the battalion's other NCOs that he was picked to lead the column more often than any of his fellow sepoy-afsars. But their complaints caused him no undue concern: he was not a man to put much store by the opinions of his peers; they were dull stolid men for the most part, and it seemed only natural to him that they should be jealous of someone such as himself.

There was only one sepoy in the paltan whom Kesri held in high regard and he was Subedar Nirbhay Singh, the highest ranking Indian in the battalion. No matter that a subedar was outranked, on paper, by even the juniormost English subaltern - by virtue of the force of his personality, as well as his family connections, Subedar Nirbhay Singh's hold on the paltan was such that even Major Wilson, the battalion commander, hesitated to cross him.

In the eyes of the men Subedar Nirbhay Singh was not just their seniormost NCO but also their patriarch, for he was a scion of the Rajput family that had formed the paltan's core for three generations. His grandfather was the duffadar who had helped to raise the regiment when it was first formed, sixty years before: he had served as its first subedar and many of his descendants had held the post after him. The present subedar had himself inherited his rank from his older brother, who had retired a couple of years before - Subedar Bhyro Singh.

Theirs was a landowning family from the outskirts of the town of Ghazipur, near Benares. Since most of the battalion's sepoys hailed from the same area and were of the same caste, many were inevitably connected to the subedar's clan - indeed a number of them were the sons of men who had served under his father and grandfather.

Kesri was one of the few members of the paltan who lacked this advantage. The village of his birth, Nayanpur, was on the furthest periphery of the battalion's catchment area and his only connection to the subedar's family was through his youngest sister, Deeti, who was married to a nephew of his. Kesri had been instrumental in arranging this marriage, and the connection had played no small part in his rise to the rank of havildar.

Now, at the age of thirty-five, after nineteen years in the paltan, Kesri had a good ten or fifteen years of active service left and he fully expected to rise soon to the rank of jamadar, with Subedar Nirbhay Singh's support. And after that, he could see no reason why he should not, in time, become the battalion's subedar himself: he did not know of a single sepoy-afsar who was his equal, in intelligence, vigour and breadth of experience. It was only his rightful due.

* * *

In the course of the last several months Zachary Reid had met with so many reverses that he did not allow himself to believe that his ordeal was almost over until he saw the Calcutta Gazette's report on the inquiry that had cleared his name.

5th June, 1839

... and this review of the week's notable events would not be complete without a mention of a recent Judicial Inquiry in which one Mr Zachary Reid, a twenty-one-year-old sailor from Baltimore, Maryland, was acquitted of all wrongdoing in the matter of the untoward incidents on the schooner Ibis, in the month of September last year.

Regular readers of the Calcutta Gazette need scarcely be reminded that the Ibis was bound for Mauritius, with two Convicts and a contingent of Coolies on board, when Disturbances broke out leading to the murder of the chief Sirdar of the immigrants, one Bhyro Singh, a former subedar of the Bengal Native Infantry who had numerous Commendations for bravery to his credit.

Subsequent to the murder, the Ibis was hit by a powerful Storm, at the end of which it was found that a gang of five men had also murdered the vessel's first mate, Mr John Crowle, and had thereafter effected an escape in a longboat. The ringleader was the Serang of the crew, a Mug from the Arakan, and his gang included the vessel's two convicts, one of whom was the former Raja of Raskhali, Neel Rattan Halder (the sensation that was caused in the city's Native Quarters last year, by the Raja's trial and conviction on charges of forgery, is no doubt still fresh in the memory of most of Calcutta's European residents).

In the aftermath of the storm the stricken Ibis was fortunate to be intercepted by the brigantine Amboyna which escorted her to Port Louis without any further loss of life. On the schooner's arrival the guards who had accompanied the Coolies proceeded to lodge a complaint against Mr Reid, accusing him of conspiring in the flight of the five badmashes, one of whom, a coolie from the district of Ghazipore, was the subedar's murderer. These charges being of the utmost gravity, it was decided that the matter would be referred to the authorities in Calcutta, with Mr Reid being sent back to India in Judicial Custody.

Unfortunately for Mr Reid, he has had to endure a wait of several months after reaching Bengal, largely because of the ill-health of the principal witness, Mr Chillingworth, the captain of the Ibis. Mr Chillingworth's inability to travel was, we are told, the principal reason for the repeated postponements of the Inquiry ...

After one of those postponements, Zachary had thought seriously about calling it quits and making a getaway. To leave Calcutta would not have been difficult: he was not under physical confinement and he could easily have found a berth, as a crewman, on one of the ships in the port. Many of these vessels were short-handed and he knew he would be taken on without too many questions being asked.

But Zachary had signed a bond, pledging to appear before the Committee of Inquiry, and to renege on that promise would have been to incriminate himself. Another, equally weighty consideration, was his hard-won mate's licence, which he had surrendered to the Harbourmaster's office in Calcutta. To abandon the licence would have meant forfeiting all that he had gained since leaving Baltimore, on the Ibis - gains that included a rise in rank from ship's carpenter to second mate. And were he indeed to return to America to obtain new papers, it was perfectly possible that his old records would be dug up which would mean that he might once again have the word 'Black' stamped against his name, thereby forever barring his path to a berth as a ship's officer.

Zachary's was a nature in which ambition and resolve were leavened by a good measure of prudence: instead of recklessly yielding to his impatience, he had carried on as best he could, eking out a living by doing odd jobs in the Kidderpore shipyards; sleeping in a succession of flea-ridden flop-houses while he waited for the Inquiry to begin. A tireless self-improver, he had devoted his spare time to reading books on navigation and seamanship.

The Inquiry into the Ibis incident commenced with a well-attended Public Hearing in the Town Hall. Presiding over it was the esteemed jurist, Mr Justice Kendalbushe of the Supreme Court. The first witness to be called was none other than Mr Chillingworth. He provided extensive testimony in Mr Reid's favour, holding him blameless for the troubles of the voyage which he ascribed entirely to the late Mr Crowle, the first mate. This individual, he said, was of a notoriously fractious and unruly disposition and had badly mishandled the vessel's affairs, creating disaffection among the Coolies and the Crew.

Next to appear was Mr Doughty, formerly of the Bengal River Pilots Service. Mr Doughty bore eloquent witness to the sterling qualities of Mr Reid's character, declaring him to be exactly the kind of White youth most urgently needed in the East: honest and hard-working, cheerful in demeanour and modest in spirit.

Kind, crusty old Doughty! Through Zachary's long months of waiting in Calcutta, Mr Doughty was the only person he had been able to count on. Once every week, and sometimes twice, he had accompanied Zachary to the Harbourmaster's office, to make sure that the matter of the Inquiry was not filed away and forgotten.

The Committee was then presented with two affidavits, the first of which was from Mr Benjamin Burnham, the owner of the Ibis. Mr Burnham is of course well known to the readers of the Gazette as one of the foremost merchants of this city and a passionate advocate of Free Trade.

Before reading out the affidavit, Mr Justice Kendalbushe observed that Mr Burnham was currently away in China else he would certainly have been present at the Inquiry. It appears that he has been detained by the Crisis that was precipitated earlier this year by the intemperate actions of the newly appointed Governor of Canton, Commissioner Lin. Since the Crisis has yet to be resolved it seems likely that Mr Burnham will remain a while yet on the shores of the Celestial Empire so that Captain Charles Elliot, Her Majesty's Representative and Plenipotentiary, may avail of his sage counsel.

Mr Burnham's affidavit was found to be an eloquent attestation to Mr Reid's good character, describing him as an honest worker, clean and virile in body, wholesome in appearance and Christian in morals. After the affidavit had been read out to the Committee Mr Justice Kendalbushe was heard to remark that Mr Burnham's testimony must necessarily carry great weight with the Committee, since he has long been a leader of the community and a pillar of the Church, renowned as much for his philanthropy as for his passionate advocacy of Free Trade. Nor did he neglect to mention Mr Burnham's wife, Mrs Catherine Burnham, who is renowned in her own right as one of this city's leading hostesses as well as a prominent supporter of a number of Improving Causes.

The second affidavit was from Mr Burnham's gomusta, Baboo Nob Kissin Pander who was also on board the Ibisat the time of the Incident, in the capacity of Supercargo. He too is currently in China, with Mr Burnham.

The Baboo's testimony was found to corroborate Mr Chillingworth's account of the Incident in every respect. Its phrasing however was most singular being filled with outlandish expressions of the sort that are so beloved of the Baboos of this city. In one of his flights of fancy Mr Burnham's gomusta proved himself to be a veritable chukker-batty, describing Mr Reid as the 'effulgent emissary' of a Gentoo deity ...

Zachary remembered how his face had burned as Mr Kendalbushe was reading out that sentence. It was almost as if the ever enigmatic Baboo Nob Kissin were standing there himself, in his saffron robe, clutching his matronly bosom and wagging his enormous head.

In the time that Zachary had known him, the Baboo had undergone a startling change, becoming steadily more womanly, especially in relation to Zachary whom he seemed to regard much as a doting mother might look upon a favourite son. Bewildering though this was to Zachary he had reason to be grateful for it too, for the Baboo, despite his oddities, was a person of many resources and had come to his aid on several occasions.

Such being the testimonials accorded to the young seafarer, the reader may well imagine the eagerness with which Mr Reid's appearance was awaited. And when at last he was summoned to the stand he did not disappoint in any respect: he was found to be more a Grecian than a Gentoo deity, ivory-complexioned and dark-haired, clean-limbed and sturdily built. Subjected to lengthy questioning, he answered steadily and without hesitation, producing a most favourable impression on the Committee.

Many of the questions that were directed at Mr Reid concerned the fate of the five fugitives who had escaped from the Ibis on the night of the storm, in one of the vessel's longboats. When asked whether there was any possibility of their having survived, Mr Reid replied that there was not the slightest doubt in his mind that they had all perished. Moreover, he said, he had seen incontestable proof of their demise with his own eyes, in the form of their capsized boat, which was found far out to sea, with its bottom stove in.

These details were fully corroborated by Captain Chillingworth, who similarly affirmed that there was not the remotest possibility of any of the fugitives having survived. These tidings caused a considerable stir in the Native Section of the Hall, where a good number of the late Raja of Raskhali's relatives had foregathered, including his young son ...

It was at this point in the proceedings that Zachary had understood why the courtroom was so crowded: many friends and relatives of the late Raja had flocked there, hoping, vainly, to hear something that might allow them to nurture the hope that he was still alive. But Zachary had no comfort to offer them: in his mind he was certain that the Raja and the other four fugitives had died during their attempted escape.

When questioned about the murder of Subedar Bhyro Singh Mr Reid confirmed that he had personally witnessed the killing, as had many others. It had occurred in the course of a flogging, when the subedar, on the Captain's orders, was administering sixty lashes to one of the coolies. Being a man of unusual strength the coolie had broken free of his bindings and had strangled the subedar with his own whip. It had happened in an instant, said Mr Reid, before hundreds of eyes; that was why Captain Chillingworth had been obliged to sentence him to death, by hanging. But ere the sentence could be carried out, a tempest had broken upon the Ibis.

Mr Reid's testimony on this matter caused another Commotion in the Native Section, for it appears that a good number of the subedar's kinsmen were also in attendance ...

Bhyro Singh's relatives were so loud in their expressions of outrage that everyone, including Zachary, had glanced in their direction. They were about a dozen in number and from the look of them Zachary had guessed that many of them were former sepoys, like those who had travelled on the Ibis as the coolies' guards and supervisors.

Zachary had often wondered at the almost fanatical devotion that Bhyro Singh inspired in these men. They would have torn his killer limb from limb that day on the Ibis, if they hadn't been held back by the officers. It was clear from their faces now that they were still hungering for revenge.

At the conclusion of the Hearing the Committee retired to an antechamber. After a brief deliberation, Mr Justice Kendalbushe returned to announce that Mr Zachary Reid had been cleared of all wrong-doing. The verdict was greeted with applause by certain sections of the courtroom.

Later, when asked about his plans for the future, Mr Reid was heard to say that he intends soon to depart for the China coast ...

And that should have been the end of it ...

But just as he was about to go off to celebrate with Mr Doughty, Zachary was accosted by a clerk of the court who handed him a wad of bills for various expenses: the biggest was for his passage from Mauritius to India. Together the bills amounted to a sum of almost one hundred rupees.

'But I can't pay that!' cried Zachary. 'I don't even have five rupees in my pocket.'

'Well, I am sorry to inform you, sir,' said the clerk, in a tone that was anything but apologetic, 'that your mate's licence will not be restored until the bills are all cleared.'

So what should have been a celebration turned instead into a wake: ale had never tasted as bitter as it did to Zachary that night.

'What'm I going to do, Mr Doughty? Without my licence how am I to earn a hundred rupees? That's almost fifty silver dollars - it'll take me more than a year to save that much from the jobs I've been doing here in Calcutta.'

Mr Doughty scratched his large, plum-like nose as he thought this over. After several sips of ale, he said: 'Now tell me, Reid - am I right to think that you were trained as a shipwright?'

'Yes, sir. I apprenticed at Gardiner's shipyard, in Baltimore. One of the world's best.'

'D'you think you're still up to snuff with your hammer and saw?'

'I certainly am.'

'Then I may know of some work for you.'

Zachary's ears perked up as Mr Doughty told him about the job: a shipwright was needed to refurbish a houseboat that had been awarded to Mr Burnham during the arbitration of the former Raja of Raskhali's estate. The vessel was now moored near Mr Burnham's Calcutta mansion. Having been long neglected the budgerow had fallen into a state of disrepair and was badly in need of refurbishment.

'Wait,' said Zachary, 'is that the houseboat on which we had dinner with the Raja last year?'

'Exactly,' said Mr Doughty. 'But the vessel's pretty much a dilly-wreck now. It'll take a lot of bunnowing to make her ship-shape again. Mrs Burnham bent my ear about it a couple of days ago. Said she was looking for a mystery.'

'A "mystery"?' said Zachary. 'What the devil do you mean, Mr Doughty?'

Mr Doughty chuckled. 'Still the greenest of griffins, aren't you, Reid? It's about time you learnt a bit of our Indian zubben. "Mystery" is the word we use here for carpenters, craftsmen and such like - men such as yourself. You think you're up for it? The tuncaw will be good of course - should be enough to clear your debts.'

A great wave of relief swept through Zachary. 'Why yes, Mr Doughty! Of course I am up for it: you can count on me!'

Zachary would willingly have started work the next morning, but it turned out that Mrs Burnham was preoccupied with the arrangements for a journey upcountry: her daughter had been advised to leave Calcutta for reasons of health, so she was taking her to a hill-station called Hazaribagh where her parents had an estate. Between this and her many social obligations and improving causes, Mrs Burnham was so busy that it took Mr Doughty several days to get a word in with her. He finally managed to catch up with her at a lecture that she had arranged for a recently arrived English doctor.

'Oh, it was frightful, m'boy,' said Mr Doughty, mopping his brow. 'A satchel-arsed sawbones jawing on and on about some ghastly epidemic. Never heard anything like it: made you want to dismast yourself. But at least I did get to speak to Mrs Burnham - she says she'll see you tomorrow, at her house. You think you can be there, at ten in the morning?'

'Yes of course I can! Thank you, Mr Doughty!'

* * *

For Shireen Modi, in Bombay, the day started like any other: later, this would seem to her the strangest thing of all - that the news had arrived without presaging or portent. All her life she had placed great store by omens and auguries - to the point where her husband, Bahram, had often scoffed and called her 'superstitious' - but try as she might she could remember no sign that might have been interpreted as a warning of what that morning was to bring.

Later that day Shireen's two daughters, Shernaz and Behroze, were to bring their children over for dinner as they did once every week. These weekly dinners were Shireen's principal diversion when her husband was away in China. Other than that there was little to enliven her days except for an occasional visit to the Fire Temple at the end of the street.

Shireen's apartment was on the top floor of the Mistrie family mansion which was on Apollo Street, one of Bombay's busiest thoroughfares. The house had long been presided over by her father, Seth Rustomjee Mistrie, the eminent shipbuilder. After his death the family firm had been taken over by her brothers, who lived on the floors below, with their wives and children. Shireen was the only daughter of the family to remain in the house after her marriage; her sisters had all moved to their husbands' homes, as was the custom.

The Mistrie mansion was a lively, bustling house with the voices of khidmatgars, bais, khansamas, ayahs and chowkidars ringing through the stairwells all day long. The quietest part of the building was the apartment that Seth Rustomjee had put aside for Shireen at the time of her betrothal to Bahram: he had insisted that the couple take up residence under his own roof after their wedding - Bahram was a penniless youth at the time and had no family connections in Bombay. Ever solicitous of his daughter, the Seth had wanted to make sure that she never suffered a day's discomfort after her marriage - and in this he had certainly succeeded, but at the cost of ensuring also that she and her husband became, in a way, dependants of the Mistrie family.

Bahram had often talked of moving out, but Shireen had always resisted, dreading the thought of managing a house on her own during her husband's long absences in China; and besides, while her parents were still alive, she had never wanted to be anywhere other than the house she had grown up in. It was only when it was too late, after her daughters had married and her parents had died, that she had begun to feel a little like an interloper. It wasn't that anyone was unkind to her; to the contrary they were almost excessively solicitous, as they might be with a guest. But it was clear to everyone - the servants most of all - that she was not a mistress of the Mistrie mansion in the same way that her brothers' wives were; when decisions had to be made about shared spaces, like the gardens or the roof, she was never consulted; her claims on the carriages were accorded a low priority or even overlooked; and when the khidmatgars quarrelled hers always seemed to get the worst of it.

There were times when Shireen felt herself to be drowning in the peculiar kind of loneliness that comes of living in a house where the servants far outnumber their employers. This was not the least of the reasons why she looked forward so eagerly to her weekly dinners with her daughters and grandchildren: she would spend days fussing over the food, going to great lengths to dig out old recipes, and making sure that the khansama tried them out in advance.

Today after several visits to the kitchen Shireen decided to add an extra item to the menu: dar ni pori - lentils, almonds and pistachios baked in pastry. Around mid-morning she dispatched a khidmatgar to the market to do some additional shopping. He was gone a long time and when he returned there was an odd look on his face. What's the matter? she asked and he responded evasively, mumbling something about having seen her husband's purser, Vico, talking to her brothers, downstairs.

Shireen was taken aback. Vico was indispensable to Bahram: he had travelled to China with him, the year before, and had been with him ever since. If Vico was in Bombay then where was her husband? And why would Vico stop to talk to her brothers before coming to see her? Even if Vico had been sent ahead to Bombay on urgent business, Bahram would certainly have given him letters and presents to bring to her.

She frowned at the khidmatgar in puzzlement: he had been in her service for many years and knew Vico well. He wasn't likely to misrecognize him, she knew, but still, just to be sure she said: You are certain it was Vico? The man nodded, in a way that sent a tremor of apprehension through her. Brusquely she told him to go back downstairs.

Tell Vico to come up at once. I want to see him right now.

Glancing at her clothes she realized that she wasn't ready to receive visitors yet: she called for a maid and went quickly to her bedroom. On opening her almirah her eyes went directly to the sari she had worn on the day of Bahram's departure for China. With trembling hands she took it off the shelf and held it against her thin, angular frame. The sheen of the rich gara silk filled the room with a green glow, lighting up her long, pointed face, her large eyes and her greying temples.

She seated herself on the bed and recalled the day in September, the year before, when Bahram had left for Canton. She had been much troubled that morning by inauspicious signs - she had broken her red marriage bangle as she was dressing and Bahram's turban was found to have fallen to the floor during the night. These portents had worried her so much that she had begged him not to leave that day. But he had said that it was imperative for him to go - why exactly she could not recall.

Then the maid broke in - Bibiji? - and she recollected why she had come to the bedroom. She took out a sari and was draping it around herself when she caught the sound of raised voices in the courtyard below: there was nothing unusual in this but for some reason it worried her and she told the maid to go and see what was happening. After a few minutes the woman came back to report that she had seen a number of peons and runners leaving the house, with chitties in their hands.

Chitties? For whom? Why?

The maid didn't know of course, so Shireen asked if Vico had come upstairs yet.

No, Bibiji, said the maid. He is still downstairs, talking to your brothers. They are in one of the daftars. The door is locked.

Oh?

Somehow Shireen forced herself to sit still while the maid combed and tied her lustrous, waist-length hair. No sooner had she finished than voices made themselves heard at the front door. Shireen went hurrying out of the bedroom, expecting to see Vico, but when she stepped into the living room she was amazed to find instead her two sons-in-law. They looked breathless and confused: she could tell that they had come hurrying over from their daftars.

Seized by misgiving, she forgot all the usual niceties: What are you two doing here in the middle of the morning?

For once they did not stand on ceremony: taking hold of her hands they led her to a divan.

What is the matter? she protested. What are you doing?

Sasu-mai, they said, you must be strong. There is something we must tell you.

Already then she knew, in her heart. But she said nothing, giving herself a minute or two to s

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...