- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

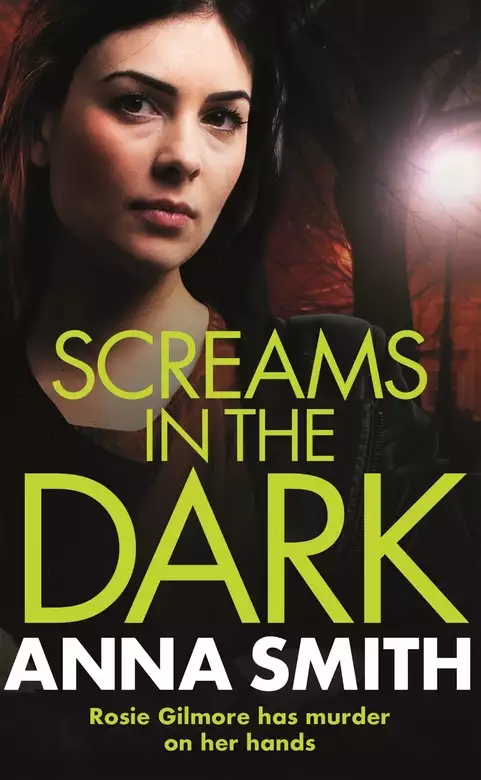

A gritty, page-turning thriller perfect for fans of Martina Cole. Refugees are disappearing in Glasgow. The mutilated body of one has been found, but the police aren't interested. Can crime reporter Rosie Gilmour uncover the truth before the killer comes for her? Steeped in its own problems, Glasgow's mushrooming underclass is simmering with resentment and the sudden flow of Kosovan refugess into the city; and one by one, refugees are disappearing. The authorities assume the refugees have vanished into the black economy, until the mutilated body of an Albanian man is fished out of the River Clyde. Asylum seekers and refugees with no roots and no families are easy pickings. But why is there no urgency from the authorities to find out what's happening? Rosie Gilmour's instincts tell her there's more to this story, but after six weeks on the frontlines in Kosovo, is her sympathy for the refugees clouding her judgement? 'Gripping and compelling' KIMBERLEY CHAMBERS 'An action packed novel with current political undertones that make for a riveting read' EUROCRIME

Release date: January 31, 2013

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 283

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Screams in the Dark

Anna Smith

The alarm didn’t beep when Tanya pushed open the door and entered the building. She stood for a moment in the tiled hallway, waiting, ready to punch in the code. Nothing. She made her way up the staircase, muttering under her breath about how careless the rich were. So careless they could leave office doors open all night for burglars. At the top of the landing, she caught her reflection in the mirror. She touched her swollen cheek and winced at the pain. Bastard. The drunken beatings were worse now that Josef had been jobless for months and spent his days boozing in the flat, while she worked at cleaning offices till she came home at night dropping with exhaustion. Fuck him. One morning, she’ll walk out and never come back, she promised herself.

The stench hit her first as she opened the door of her boss’s office – and then she saw him. Tony Murphy was hanging from the ceiling, his chair beneath him lying on its side. Her hand went to her mouth and she steadied herself against the wall as she felt her legs buckle. She closed her eyes, but the grotesque image was still there: the face blue, one eye bulging like a gargoyle, the other slyly half open, the swollen tongue poking through blue lips and hanging to the side. Tanya gagged, feeling the sick rise in her throat.

The closed venetian blinds clanked and fluttered at the open window. She turned to look again at Tony’s distorted face, shaking her head in disbelief. Then tears stung her eyes. Yesterday in the hotel room where they had their secret trysts, he’d told her again how much he loved her. Again, he promised he would leave his wife and they’d be together. Liar. She closed her eyes and pictured him turning her over in the bed in the throes of passion so he could come in his favourite position, and remembered how, afterwards, they’d lain there, spent and in each other’s arms.

‘Why, Tony?’ she sobbed into her hands. ‘Why?’ She slid down the wall and sank to the floor. Tony had made her believe that life was full of so many possibilities if you loved enough. Now the dream had turned into a garish, terrifying nightmare, and the reality was there was no escape from the life she had.

Eventually Tanya glanced up at the clock on the wall. It was nearly 9.30. She had to compose herself, pull herself together. She got to her feet and stood sniffing, wiping her face with the back of her hands. She took a step towards the desk, where she squinted at two envelopes addressed in Tony’s handwriting – one to Millie, his wife, the other to Frank, his partner in the law firm. She picked them up and shoved them under her vest, then tucked it into her trousers. She looked up at Tony’s body, and the tears came again.

Tanya was backing out of the office when she heard the front door open. She staggered to the top of the stairs and started screaming as Frank Paton, startled, ran up the stairs towards her. She couldn’t speak, but just pointed in the direction of the room.

‘Oh Christ! Oh Christ no, Tony! Call an ambulance, Tanya. Hurry.’ He covered his mouth and nose with his hand.

‘He’s dead, Mr Frank. You can see he’s dead,’ she said through sobs.

Paton looked at her, then up at Tony’s body, twisting at the end of the rope. He took out his own mobile and dialled 999.

‘This is Frank Paton, of Paton, Murphy Solicitors, in Renfield Street.’ He took a breath. ‘My partner Tony Murphy has hanged himself … What? … Here, in his office … I just came in, the cleaner found him … He’s hanging from the ceiling. He’s dead.’

He turned to Tanya, his eyes full of tears. ‘They’re on their way.’ He swallowed.

Tanya watched as Paton went to Tony’s desk and lifted a buff folder full of papers. It was marked ‘Asylums Pending’. Underneath, written in thick black felt pen, were the names of several countries – Somalia, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Kosovo, Albania, Iraq, Syria, Turkey.

‘No note. Can’t believe it. Nothing. Not even for Millie.’ Paton closed his eyes, and pinched the bridge of his nose with his thumb and forefinger. ‘Oh, Millie. What am I going to say to you?’ He whispered to himself.

He stood for a moment, looking around the room, then bent down and went into the open safe in the corner. He took out three more bulging files and left the room.

*

At around the same time, across the city, Ben Gates steered his boat up the River Clyde, where a crowd had already gathered on the walkway despite the steady drizzle. People always stopped for a look when a body was found in the water. Morbid curiosity. Ben had seen it all before. He waved at the uniformed cops standing on the embankment, but he didn’t need them to direct him. He could see it already, bobbing in the current. He carefully eased his boat closer to the body, but his trained eye knew straight away. He took out his mobile and called the Strathclyde cop who had phoned him twenty minutes earlier at the Glasgow Humane Society to say they needed his help.

‘Jim … it’s just a torso.’

‘What? You winding me up, Benny? I’m trying to eat a fried egg roll here.’

‘Seriously, Jim. Torso.’

‘No legs or anything?’

‘Christ sake, man. Do you not know what a torso is? You’d better get rid of the ghouls up there before I bring it in.’ He hung up.

Ben pulled his boat around so it shielded the torso from the gaping crowd. Whoever belonged to the remains in front of him had been a living, breathing person at one time – recently in fact, judging by the looks of things, the colour of the raw flesh where the arms and legs had been severed. He picked up the oilskin and expertly cast it across so the body was covered and snared, enabling him to drag it towards him. When it was close enough he gripped the ropes and dragged it onto the boat, easing it over the side and gently laying it on the bottom as though he was handling a precious child. He didn’t touch it, or lift the cover back. His father had always taught him that curiosity wasn’t his job. His role was to preserve the dignity of the poor soul they’d recovered, and take it towards its final journey. He slowly made his way to the embankment, where he could see the cops already pushing everyone back.

Ben tossed the rope to the young cop standing at the edge, trying to keep his feet on the slippery, muddy bank, and turned off his engine as the two cops hauled the boat up the slope inch by inch. The ambulance men made their way down with a stretcher. Ben could hear the big Strathclyde Police sergeant on his radio telling them to send transport. The boat, with the torso still in it, would be taken in a low loader to the mortuary so that everything would be kept intact for the post-mortem. Not that there was much left to examine.

‘Fuck me!’ the sergeant said as the two officers pulled back the cover. He bent down, peering at the chest.

‘What the fuck’s that? Is it tattoos?’

‘Tattoos?’ the paramedic sniggered.

‘Well, what is it?’ the sergeant screwed up his eyes.

‘Stitches,’ the paramedic said. ‘Looks like they’ve been done by a blind person wearing boxing gloves. But it’s stitches. Rough-looking job all right.’

‘Stitches?’

‘Aye.’ The paramedic turned to his partner, then to the sergeant. ‘Somebody’s opened this guy up. Something well dodgy here. We’d better not touch it till the CID come.’

*

One man held the key to these two grisly scenes, but he was nowhere near them. Tam Logan was so cold he couldn’t keep his eyes open. The blood on his temple where they’d hit him with the butt of the gun had congealed hard. He tried to focus on his wristwatch but it was a blur. He guessed he’d been in the back of the refrigerated van for nearly two hours.

Suddenly there was the sound of bolts being slid and someone pulled the door back. Tam tried to sit up, but his hands were tied and he slumped against the side. He heard voices outside, and shook himself, trying again to get up and this time managing to make it to his feet. Two men wearing balaclavas climbed into the back of the van and stood over him. His stomach lurched when he saw their guns. They stood in silence as another man climbed in and looked down at him. He wasn’t wearing a balaclava, and Tam recognised him as the man they called Doctor Mengele – though never to his face. He’d seen him before at the plant, dressed in his white coat, and he knew he was a foreigner. They’d said he was from Bosnia and he was the boss, but nobody knew his name.

‘What were you doing?’ The Doc eyed him coldly.

Tam said nothing. He tried to swallow but his mouth was dry.

‘Why did you steal it? Did you think we would never find you?’

Tam shook his head. ‘I don’t know. I’m sorry.’ He could feel his knees shaking.

The Doc stared at him again, then took a deep breath and gave a bored sigh. He looked at one of the masked men.

‘Kill him.’ He turned and walked away.

Rosie parked her car and walked towards the noise. It was supposed to be a protest, but it looked more like an unruly mob.

‘What do we want?’ bellowed the fat woman standing on the low wall.

‘Equal rights,’ the crowd chanted back.

‘When do we want them?’ She was whipping them up.

‘Now!’ Clenched fists punched the air for emphasis.

Equal to what, Rosie wondered, as her footsteps scrunched on the broken glass from bottles tossed by the obligatory thugs who would turn up anywhere looking for a fight.

She stopped for a moment and gazed up at the notorious Red Road flats, a bleak cluster of eight massive tower blocks scarring the skyline. It must have seemed like a good idea at the time to house families in slabconcrete blocks thirty-one storeys high. But then it was the sixties, so you had to assume that whoever sanctioned it was off their tits on drugs. Because in a few short years high living, as the flats were dubbed, had become low-life dens, with junkies and drug dealers on every floor. And at least twice a year some poor bastard took a swan dive from the twentieth floor, either because they’d been shoved or had simply run out of hope.

From where Rosie was standing, it was hard to see what this lot were fighting over, but she’d decided to come up to the Balornock housing scheme in the north of Glasgow and see for herself. The protest had been staged by the angry residents of the council flats who’d become incensed at what they claimed was special treatment for asylum seekers. Charity begins at home, said one of the banners. Go home foreigners, exclaimed another. She sighed. Welcome to Glasgow – the city with the big, bleeding heart.

‘You fae the papers?’ A lantern-jawed man sucked on a roll-up cigarette as he approached her.

Rosie looked at him and paused before she answered. On a scale of the most unwelcome guests in a place like this, number one was the cops, two was the DSS snoops, three was anyone from the papers.

‘Yeah,’ she took a chance. ‘The Post. Came up to see what all the protest is about. Can I ask you exactly what’s happening?’ Not that she didn’t know.

‘What’s happening?’ His voice went up an octave with indignation, and Rosie got a whiff of just-drunk booze. ‘What’s happenin’ is these fuckin’ foreigners are gettin’ everythin’ handed to them on a plate and we get fuck all.’

‘Really?’ Rosie tried to look sympathetic. ‘Like what?’

‘Hoovers,’ he said. ‘And kettles. Washin’ machines. Stuff like that. They come skiving in here from some foreign place and get a council house, fitted carpets, new kitchens. But if you’re born and bred in Glasgow you just get in the queue behind them. We’re like second-class citizens. It’s pure shite, by the way.’

Rosie nodded. ‘I see what you mean.’

But she didn’t really. Sure, it might not have been clever to accommodate the sudden influx of asylum seekers in Balornock, one of the most socially deprived housing schemes in the city. But Rosie could bet if you did a straw poll of every Balornock council tenant who wasn’t a refugee, you’d find that two in three of them had Irish grandparents. If they were to take their heads out of their backsides for a moment, they might consider that their own ancestors were themselves half-starved, impoverished refugees from Ireland who came over here on the boat with nothing but the clothes they stood in. And right now, the very people waving placards were second or third generation from those refugees who fled violence and bigotry in their own country. But if you were ten floors up and skint on a Friday, with your man on the dole and four hungry kids, you jealously guarded what little you had.

The sound of glass crashing and people screaming made them both turn towards the crowd.

‘See what I mean? This could end up in a riot. Fuck them.’ The man took off at speed towards the youths throwing bottles.

A police van drew up and a bunch of uniformed officers jumped out and headed towards the mob. Rosie followed close behind. Another police van arrived with reinforcements and they headed to the front of the crowd to form a human chain. Rosie weaved her way through the mob to see what had triggered the trouble.

In front of the Red Road flats, she could see two minibuses full of people, refugees by the look of fear on their faces as bottles rained down on them, bouncing off the windows. Children screamed from inside the bus.

‘Get to fuck back to wherever you came from,’ a skinny woman spat from the crowd.

‘You don’t belong here,’ another screamed.

Half a dozen police officers went across to one of the minibuses and began to let the people out one by one, escorting them inside the building, while the rest of the cops stood holding back the crowd.

Rosie watched as the terrified refugees stepped out, some of them in tears, all of them with the haunted, deathly pallor she’d witnessed in conflicts all over the world. Her mind flashed back to Kosovo, still fresh and raw enough to make her stomach turn over. She’d only come back two months ago after six weeks on the frontline, and the images of the traumatised Kosovo Albanian refugees, beaten and bloodied by the Serbs, continued to haunt her sleepless nights. That was partly why she’d suggested to McGuire, her editor, she should come up to Balornock to see just what was going on with this discord over asylum seekers building up a head of steam. Already, there had been several random attacks on refugees in the scheme, apparently the work of vigilantes determined to run the foreigners out.

Now, just seeing the faces being helped out of the minibus and into the flats, Rosie was back in the muddy field in the border post in Blace, as stricken refugees staggered into Macedonia, each with a horror story of what they had suffered at the hands of Serbian soldiers who butchered their way through towns and villages. To survive all of that, and then end up here? Where you were a figure of hate because you had a fitted carpet? Christ almighty! Rosie looked back at the crowd and felt ashamed of her fellow countrymen.

Her mobile rang in her pocket and she fished it out.

‘You still up in Balornock, Rosie?’ It was Lamont, the news editor, whom she despised and seldom had to deal with.

‘Yeah, why?’

‘McGuire wants you back down here. Tony Murphy’s just been found hanged in his office. Oh, and there’s a torso been fished out of the Clyde. I’ve sent Reynolds over on that one. But McGuire wants you back.’

‘Fine. What’s the story with Murphy?’

‘Dunno. He does mostly refugees these days. Asylum cases. Who knows?’

‘I’m heading back anyway. I’ve seen enough here.’

Rosie didn’t need to sell the news feature on refugees to Lamont. She knew he’d be negative, as he always was with every idea she put up – backstabbing bastard that he was.

The police seemed to have calmed the situation, and the crowd began to disperse, so Rosie made her way across the back court to her car. As she walked past the back entrance to the flats, she stopped when she saw a young man standing against the wall. He looked Bosnian or Kosovan, or he could have been Turkish – it was hard to tell. But he was definitely a refugee, she decided. He had that lean, lost look they all had. He stood there weeping, his lip quivering. Rosie watched him for a moment and he looked through her, tears running down his face. He was obviously in some kind of meltdown.

‘What’s the matter?’ Rosie went over to him. ‘Is there anything I can do. Are you sick?’

He shook his head. ‘English no very good. I am Kosovan.’ He sniffed and wiped his face, seeming to compose himself.

‘You living here?’ Rosie pointed to the flats.

He nodded.

‘How long you been here?’

‘One month.’ He started crying again. ‘I alone. My mother, my father …’ He drew his hand across his throat. ‘They killed.’

‘The Serb soldiers?’

He nodded.

‘Do you not have friends here? Other Kosovo refugees? There are a lot of Kosovan people here now.’

He shook his head and bit his lip. ‘My friend. They take him.’

‘Who?’ Rosie asked. ‘Who took him?’

He took a cigarette out of his jeans pocket and his hands trembled as he lit it.

‘I not know.’ He glanced over his shoulder.

Rosie screwed her eyes up, confused. ‘What do you mean?’ she asked.

‘I run away. They take my friend. I not know where he is.’ He wiped his tears with the palm of his hand.

Rosie automatically extended a hand of comfort, but he flinched and drew back.

‘Let me take you for a cup of tea.’ She pointed to the cafe across the road. ‘We can talk there. Maybe I can help you.’

He shook his head, and began to back away.

‘Don’t be afraid. It’s okay. My name is Rosie. Rosie Gilmour. I am a journalist. Do you understand? Newspaper?’

He nodded, then shook his head. ‘I am frightened. I must go.’ He began walking away, with Rosie pursuing him.

‘Please. Wait. Hold on. Please.’ She caught up with him and he stopped. She reached into her bag and pulled out her business card. ‘I just want to give you this.’ She held out the card. ‘It’s okay. I promise.’ She reached out and touched his arm. ‘Don’t worry. I want to help you. I was in Kosovo in April. I was there. And in Blace. I saw … things.’

He seemed to calm down a little. He looked at her, took the card and put it in his pocket.

‘What is your name?’ Rosie asked.

He paused and looked around him.

‘Emir,’ he whispered. ‘My name is Emir.’

Some of the protesters were making their way across the car park, and he glanced at them.

‘I go.’ He backed away.

‘Emir. You can phone me. Any time. I will come.’

‘Dear oh dear! Two stiffs and it’s not even lunchtime,’ McGuire chuckled as Rosie walked into his office. ‘This never happens when you’re not involved Gilmour. Must be down to you.’

‘Yeah, very funny, Mick.’ Rosie plonked herself on the leather sofa opposite his desk. ‘You should try and incorporate that air of sympathy the next time you’ve got a funeral eulogy to make.’

‘Ha! That’s good coming from you,’ he grinned. ‘By the time you got home from Spain last July, there were bodies everywhere. By the way, is that paedo Vinny Paterson still trying to climb out of the well your mates chucked him down in Morocco?’

‘Touché,’ Rosie half smiled, ‘but I can assure you this morning’s unfortunate stiffs have nothing to do with me.’

‘Don’t worry, Rosie. We’ll soon change that.’ McGuire took off his reading glasses and placed them on his desk. ‘That’s a real shocker about Tony Murphy. Hanging from the ceiling in his office? Very strange. Got to be something dodgy there. I feel a scandal coming on. What’s the word on the street?’

Rosie sat back and rubbed her face with her hands. The whole protest scene up the road had somehow exhausted her.

‘I talked to one of my lawyer pals on the way back from Balornock. Like everyone else, he’s stunned. Murphy seemed to have it all. Married, two kids at university, big house, didn’t appear to have money worries. Mostly did a lot of refugee work in the past couple of years, helping asylum seekers stay in the country, fighting for their rights. All that sort of stuff. Wasn’t always like that though.’

‘Yeah, I’ve seen his face on the telly talking about refugees. What do you mean?’

‘Few years ago,’ Rosie said, ‘he and his partner Frank Paton were more into criminal law. They defended any hoodlum with a wedge of money, or some lowlife toerag as long as they got legal aid. You could sometimes see the pair of them in O’Brien’s with a couple of wellknown gangsters. I’ve seen them myself a few times, but not for a while. I thought it was a bit strange that they suddenly became these white knights fighting for poor bastard refugees. They never struck me as woolly-headed liberals.’

‘Money, Rosie,’ McGuire said. ‘It’s all about money. These lawyers fighting asylum cases make a fortune in legal aid fees. It’s all appeals, fights against deportation, long drawn-out hearings. Every time some asylum seeker turns up at a lawyer’s office, the tills start jingling like Christmas Eve.’

‘True,’ Rosie agreed. ‘That sounds like Paton and Murphy. Naked greed. But why hang himself? He must have been into something. I’m waiting for a few people to get back to me, in case he was into drugs or anything.’

‘Any suicide note?’

‘Nothing. It might not have been suicide. Maybe it was just made to look that way.’

McGuire raised an eyebrow. ‘Is that just your vivid imagination, Gilmour, or are you basing it on actual evidence?’

Rosie paused. ‘No, nothing really. But something drove him to suicide, Mick. I’m going to do a bit more digging.’

‘Good. Nothing like a bit of intrigue to give a shape to the weekend – as long as the Sundays don’t come up with any revelations about what made Murphy cash in his chips.’ He turned to his computer screen. It was time to go.

‘Oh, Mick,’ said Rosie as she stood up. ‘Talking of intrigue, something else up at the Red Road.’

McGuire was still looking at his screen.

‘Never mind,’ Rosie said. ‘I’ll tell you later.’

‘What, Rosie?’ He looked up. ‘Don’t fuck about.’

‘Well, it’s just that as I was about to leave the protest, I came across this refugee. A Kosovan guy, late twenties or early thirties. Always hard to tell with refugees as they’re kind of old before their time. But he was crying.’

‘Crying?’

‘Yeah. At the back of the flats. Just standing there sobbing by himself. My heart went out to the guy. Poor bastard is probably traumatised by everything in Kosovo and just feels desperate and alone. Who knows, but I went over and spoke to him.’

‘Go on.’

‘He didn’t speak great English, but from what I understood his parents were murdered by Serb soldiers. Then he said he was alone now, that he’d been here a month, and that his friend was taken.’

‘Taken? Here or in Kosovo?’

‘Here. He said “my friend they take him”, and then he said that he ran away. But when I pressed him for more information he just backed off. The guy was absolutely terrified. Something has happened, but I don’t know what. I gave him my card, and told him I’d been in Kosovo. I think he’ll phone me.’

‘How can you tell?’

‘Sometimes you just know, Mick. I feel it. He’s got something to tell and he just doesn’t know how to yet, but something has scared the shit out of him. And his pal is missing.’

‘You need to find him, Rosie. Can you stake out the flats?.’

‘If it comes to it I will. But I’m hoping he gets in touch before I have to do that.’ Rosie changed the subject. ‘What about the torso? Any word on that? What’s Reynolds saying?’

‘Not much. All we’ll get from him is what the cops want us to get. He told Lamont that cops are still trying to identify it, but they’ve revealed it’s a male. These plods are amazing. I guess they came to that conclusion because the torso had no tits.’

Rosie chortled.

‘I’ll see what else we can find out as the day goes on, but I want to have a better look at Tony Murphy. Find out a bit more about his work as a refugee lawyer. I’ll talk to some contacts.’

‘Fine,’ said McGuire, ‘but I hope your weeping refugee guy phones you. He sounds interesting. Either that, or back in Kosovo they told him he was going to Madrid or somewhere exotic, and he’s just depressed he ended up in Balornock in the rain.’

*

Tanya sat in the cafe, sipping coffee and drawing the smoke from her cigarette deep into her lungs as though her life depended on it. She ran a hand over her face and leaned back, so exhausted she could barely keep her eyes open. She ordered another coffee, black this time.

The questioning by the police when they’d descended on the offices of Paton, Murphy was much more involved than she’d imagined. While the paramedics and medical team worked in Murphy’s office, two detectives had taken her to another room. They sat her down and reassured her their questions were just routine, but they needed a statement from her of exactly what she found when she’d arrived at the offices. She turned down their offer of an interpreter, telling them she’d been in Glasgow for nearly three years and understood the language. The female detective had made her a cup of tea and talked sympathetically to her, as Tanya gave them an account of what she’d found. All during the interview she could feel sweat trickling down her back and was glad she’d tucked the letters into her bag before they spoke to her. Eventually they told her she could go. As she left, she put her head around the door of Frank Paton’s office, where he sat staring into space.

*

Now, glad the cafe was almost empty, she sat in the corner booth furthest away from the counter and took out the letter Tony had addressed to Millie. She opened it carefully, took out the single sheet of notepaper and read it slowly, her heart sinking with each line:

Dear Millie,

The picture of your lovely face, and our smiling, beautiful children, is the last image I see. Please forgive me. I could not go on any more with the lies. I love you forever, always have. I’m sorry. Tony.

There were three kisses at the end.

The knot in Tanya’s stomach turned to anger. It had all been one big lie. Everything. He’d never had any intentions of leaving his fam. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...