- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

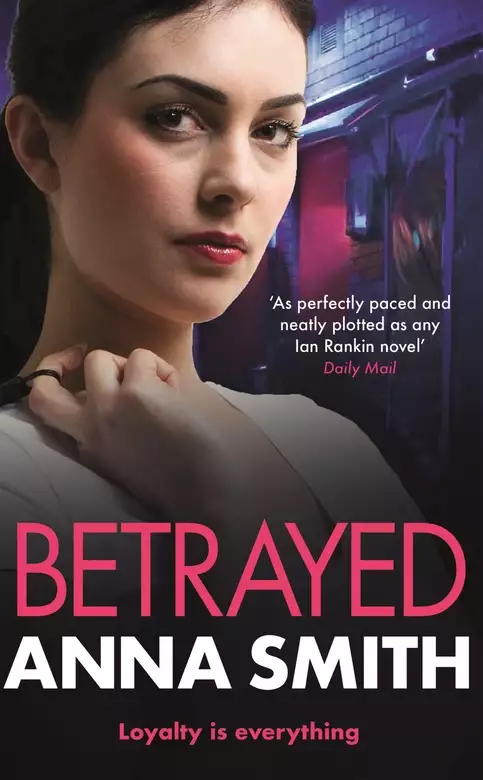

Synopsis

Rosie Gilmour is chasing an explosive new story that will take her deep into Glasgow's sectarian underworld. But has she got in over her head? Crime reporter Rosie Gilmour is on the trail of missing barmaid Wendy Graham. Wendy's boyfriend is a member of the Ulster Volunteer Force - and before she vanished, she levelled a horrifying accusation against one of his mates. Determined to get justice for a woman she is sure has paid the ultimate price for breaking the silence of the UVF brotherhood, Rosie will find herself at the mercy of the most vicious gangsters she's ever encountered. Has she met her match this time? 'If you haven't come across Rosie yet, this jet-propelled and cleverly plotted story will suck you in from page one and send you searching for her earlier adventures' Crime Review

Release date: April 24, 2014

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 289

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Betrayed

Anna Smith

They belted the song out to the beat of the Lambeg drum.

‘Do you know where hell is, hell is in The Falls … Heaven is the Shankill and we’ll guard those Derry’s walls … I was born under a Union Jack … A Union, Union Jack …’

‘What a night, Jimmy boy! Fucking rocking!’ Eddie McGregor stood at the bar, his arms folded across his chest as Jimmy Dunlop came up beside him.

‘Aye. Class, man.’ Jimmy winked to the barmaid whose face lit up as she smiled back.

‘You’ll be a proud man tonight, Jimmy, eh?’ Eddie dug him in the ribs with his elbow. ‘Your da’s well made up over there. Look at him.’

Jimmy smiled, squinting through the fug of smoke where his father was leading the sing-song at his table, whisky in hand, face crimson from drink and exuberance. Two of the guys next to him stood on chairs, swaying, arms around each other’s shoulders as one song followed another in a medley of the sectarian hate they’d all grown up with.

‘That’s your wee bird there, isn’t it? You giving her plenty, you rascal?’ Eddie jerked his head towards the barmaid as she stretched up to the optics on the gantry. He grinned, his tongue darting out to lick his lips as she bent over in her skintight jeans. ‘She’s well fuckable. I’ll tell you that.’

Jimmy caught a whiff of Eddie’s sweat and felt a little disgusted. He said nothing, but forced a smile because he knew he was expected to. After all, Eddie was his commanding officer now. He hoped his face didn’t show the stab of resentment he felt at Eddie’s remark. Wendy was his. He couldn’t get her out of his mind. One of his mates had told him Wendy was easy – and maybe she was. But he’d been seeing her for nearly two months now and he felt different when he was with her. When he’d told her he was determined to hold onto her, tears had welled up in her big brown eyes and she was suddenly so unlike the brash barmaid, quick to slap down a smart-arsed customer despite her skinny frame. It was there and then that Jimmy saw where he wanted to be for the rest of his life.

He took a long drink of his pint, rolled up his shirtsleeves and tried to relax for the first time all evening. The hall was heaving. It was billed as an all male smoker night for Rangers football supporters. But everyone who’d bought a ticket knew it was in fact a fundraiser for the Ulster Volunteer Force. It was nights like this that Loyalist hardliners lived for, and Jimmy had been to plenty of them. It had kicked off with a bit of stand-up by a famous Glasgow lawyer, ripping the pish out of Catholics and Celtic. But the highlight of the night was the parade around the hall led by the ‘colour party’ of UVF heroes in balaclavas, who’d come all the way from Belfast. They’d made their entrance in dramatic fashion as a hush fell over the room. Once the outside doors had been locked and secured, they emerged from a side room, in full paramilitary uniform, bearing rifles on their shoulders as they marched beneath the UVF flag. Then followed a rousing call-to-arms speech by the Belfast brigadier. And there, among the official stewards, in their black trousers and crisp white shirts, one Jimmy Dunlop, the newest recruit to Glasgow B Company, Number Two Platoon, proudly wearing his new UVF tie – the badge of honour that put him a cut above the rest.

On the stroke of midnight, with a brisk drum roll and flutes at the ready, the Portadown Sons of William Flute Band assembled in the centre of the hall for the national anthem. The crowd of three hundred revellers, sweating like horses in the heat of the sweltering summer’s night, stood with their chests bursting with pride as they sang ‘God Save the Queen’. And on the final line, a chorus of lusty roars of ‘No Surrender’ and ‘C’mon, the Rangers’ rang out around the hall.

‘All right, Jimmy boy?’ Mitch Gillespie staggered up and slung an arm around his shoulder.

‘Great, Mitch. Couldn’t be better.’ Jimmy drained his pint and placed the tumbler on the bar.

He was a little light-headed, having already downed half a dozen pints in quick succession after staying sober for his stewarding duties earlier. He kept one eye on Wendy clearing up behind the bar. He wouldn’t be able to go back to her place, as his da was so blootered he’d have to see him home. But he was hoping to get a snog at her round the back of the pub before she left. Big Eddie was giving the barmaids a lift home, as he’d only had three pints the whole night.

‘C’mon, we’ll go to the dancing,’ Mitch said, dragging him away from the bar. ‘I need a ride, man. Make up for lost time.’ He grinned.

‘Yeah, sure you do,’ Jimmy grinned. ‘But don’t start getting fresh with me. Your arse must be like a ripped-out fireplace, after all that any-port-in-a-storm stuff in the nick.’ He shrugged Mitch’s muscular arm from his shoulder and slapped him on the back.

‘That’ll be fucking right,’ Mitch snorted derisively. ‘No’ me. Even when I was gagging for it, I wasn’t going to let some big randy fucker in the boys’ gate.’ He chuckled. ‘Mind you, once or twice I nearly let somebody blow me.’

Jimmy laughed, part of him full of admiration for Mitch being able to handle six years banged up for culpable homicide. But a bigger part of him was still revolted at what he and his mate witnessed seven years ago during a mêlée after an Old Firm match. They’d been sent to the East End by big Eddie to find Mitch, and when they got there, he was coked out of his nut, jumping on the head of a Celtic fan, the guy’s face like something from a butcher’s dustbin. It was fair enough to give somebody a hiding in a fight, but this was bang out of order. They dragged Mitch off and bundled him into a car. But the cops caught up with him within twenty-four hours and he was locked up. Mitch, or Mad Mitch, as the newspapers dubbed him at the trial, had only been released from jail five weeks ago after his sentence was reduced on appeal. He’d come through the prison doors of Barlinnie like a prize fighter, arms like hams and muscles rippling through his skintight T-shirt, and a wide grin across his face as he strutted towards Jimmy’s waiting car. Then he turned and pumped his fist defiantly at the building and shouted, ‘It was a fucking walk in the park, you cunts!’

‘Nah, Mitch. I can’t go anywhere tonight. Look at my da. He’s blitzed. I’ll need to get him home. Maybe tomorrow night, mate.’

‘Right, okay, pal.’ Mitch walked away, giving him the two thumbs up. ‘You’re the man, Jimmy. I love you, man.’

Jimmy watched as he went unsteadily towards a group of young men, who were all drunk and who knew Mitch well enough by reputation not to object to him barging in on them.

*

Half an hour later Jimmy struggled up the tenement stairs with his father hanging onto him. He was still singing the ‘Billy Boys’ at the top of his voice.

‘Sssh, da. You’ll get us fucking shot.’ Jimmy knew that at least two of the downstairs neighbours were diehard Celtic fans.

‘Aye. That’ll be fucking right. Them pikey bastards can fuck off back to the bogs,’ big Jack Dunlop slurred, his Belfast accent still as strong as the day he left his home city for Glasgow forty years ago. ‘Any shooting to be done round here, I’ll be doing it.’ He stood on the landing, swaying as Jimmy put the key in the door. ‘You just remember who you are, Jimmy. You’ve got a fucking pedigree that goes all the way to the Shankill.’

His father burst into song as Jimmy gently wrestled him inside the doorway. ‘Follow, follow, we will follow Rangers … up the stair, down the stair, we will follow you …’

The mobile ringing on his bedside table woke Jimmy with a start. He looked at his watch. He must have dropped off, because it was only one thirty in the morning and he still had his clothes on. He saw Wendy’s name on the screen and cleared his throat.

‘Hiya, Wendy. Still up? You missing me?’

Silence. Then Jimmy thought he heard sobs.

‘You there, Wendy?’ His stomach lurched.

‘Oh, Jimmy.’ Her voice was a whisper.

‘Wendy. You all right? What’s wrong?’

‘Oh Jimmy.’ More sobs. ‘He …’

‘What’s wrong? Calm down.’ He was on his feet. ‘You been in an accident or something? Are you hurt?’

‘No … Oh … Yes … He …’ Wendy sniffed. ‘He raped me, Jimmy.’

‘What? Who? Who raped you?’

‘Eddie.’ She dissolved into sobs. ‘Eddie raped me … In his car.’

‘Aw fuck! Aw fuck no, Wendy! Eddie raped you? I’ll fucking kill him.’ Red-hot anger burned from his stomach to his throat. ‘You in the house?’ He shoved his feet into his trainers.

‘Uh huh … ’

‘Wait there. I’m coming over right now. I’ll get a taxi.’ But when he got there, Wendy was gone.

The marching season. All human forms are here, Rosie thought, judging by some of the rat-arsed, drunken knuckletrailers on the sidelines. She stood for fully ten minutes in the sunshine, watching the Orange Walk in its swaggering stride through Glasgow city centre, like a conquering army with a jaunty tune. Then she weaved her way through the Bath Street hordes on the pavement till she could find a place to cross the road without cutting through the marchers. That was more or less a hanging offence. Or at the very least you’d get your face wasted if you dared to barge through the parade of flute bands, or the well-dressed ladies in straw hats, or, worst of all, the strutting men in bowler hats and brollies, resplendent in orange sashes – no doubt the very ones their fathers wore.

Rosie needed this like a hole in the head – especially on a Saturday morning with a hangover. She walked briskly until she reached the head of the parade and made a dash across the road. Her mobile rang in her bag and she rummaged through, fishing it out.

‘That you, Rosie? I’m in the bar waiting for you.’

‘I’m there in two minutes, Liz. The city centre’s mental, with the walk being on.’

Rosie recognised the voice of the woman she’d met yesterday, the woman who had shut the door in her face when she told her she was working on the story of the missing barmaid, Wendy Graham. It was now over three weeks since she vanished after finishing her shift in the bar that had been hosting a Rangers supporters’ smoker night, and the story was falling so far down the news schedule it barely got a mention. The media very quickly lose interest in a missing person unless it’s a child or a celebrity, or unless there is some glaring sense that the missing person is about to turn up dead. The police would tell you that their files are chock full with people who just disappeared into thin air, but Rosie had pushed the editor to keep a line in the newspaper, hoping she’d get a call that might open the story up. She was even more intrigued after her Strathclyde Police detective friend tipped her that Wendy Graham’s sudden disappearance might be more than just a missing person.

When Wendy’s pal Liz had refused to talk to her, it only added to her interest in the story. Rosie had slipped her business card below the door as she left the tenement, but she didn’t really expect a call. The knockback had been fairly emphatic, laced with a few expletives. So when the call did come last night as she was out at a farewell party for one of the Post’s feature writers, Rosie knew she would have to be available any time, any place. Even on a Saturday morning. It should have stopped her carrying on for a full house and ending up at a nightclub till three. But it didn’t. She was feeling a little fragile as she went downstairs to the basement bar for her meeting. She hoped it wouldn’t last too long.

The Unit Bar was empty and the air was thick with the reek of stale cigarette smoke and alcohol, mixed with last night’s sweaty bodies. Bars the morning after were always lonely, depressing places; a kind of stiff reminder that there was always the cold light of day to bring you crashing back to reality, despite the hopes and possibilities of the night before. And the Unit was one bar where the possibilities were endless – ecstasy tablets that were circulated like sweeties; or some speed; or if you were hard core and past caring, a few grams of crack – the latest lethal fix with more terrifying implications than the heroin explosion of the last decade. But like every form of refuge, there was a price to pay. So whoever was here last night off their face on drugs was now probably festering in some housing scheme, or city centre flat, or student digs, coming down to earth with paranoia and loathing crushing their head. And, of course, the pressing urge for more.

Rosie felt a little nauseous and took as deep a breath as she dared, squinting across the dingy room where she spotted Liz at the fake leather seating in the far corner. She walked across, feeling her feet sticking to the carpet. Classy joint.

‘Liz,’ Rosie stretched out her hand, ‘thanks for coming.’

Liz shook her hand and gave her a sheepish look.

‘Sorry about yesterday.’ She shifted in her seat. ‘I mean, shutting the door in your face. I’m just under a bit of pressure. You know. Wendy going missing and that.’

Rosie sat down.

‘No worries, Liz. If I’d a pound for every time someone shut the door in my face, I’d have chucked work years ago and retired somewhere sunny.’ She looked at her almost empty glass. ‘Let me get you a drink.’

‘Vodka and diet Coke,’ Liz said, swirling the remains of her drink. ‘I’m only having a couple. It’s not often I’m on this side of a bar.’ Then she looked up at Rosie as though attempting to justify being on her second vodka before midday. ‘I haven’t been drinking much in the past month … Since Wendy disappeared.’

Rosie nodded. ‘I’ll get the drinks in and maybe we can have a chat, if you’re all right with that.’

She returned to the table with a glass of mineral water for herself and watched while Liz poured the dregs of her glass into the fresh one and took a swig. She was built like a pit pony, and looked like a thirty-something bottle-blonde who had been around the course a few times. Rosie imagined that she wouldn’t take any crap from customers on the other side of the bar. She hoped she wasn’t as hard as she looked.

‘I’m surprised there’s not been a lot in the papers,’ Liz said, lighting a cigarette and flicking a glance at Rosie. ‘A lassie’s gone missing. Nearly a month now. You’d think the papers would make more of it.’

There was a tone of reprimand in her voice.

‘Yeah,’ Rosie said. ‘I’ve done a few pieces myself but I get the sense that the story is slipping off the news agenda. I’m trying to keep it alive, look for new lines.’ She gave Liz a look that let her know who was running this meeting. ‘Which is why I’m here, and what I was trying to do yesterday.’ Rosie paused and pushed her hair back. ‘Do you want to tell me a bit about it? All I know is that Wendy and you were friends and that she was working in a bar at some Rangers smoker night and then went home with you. I think the two of you got a lift home with someone called Eddie McGregor, according to what the cops put out? He was one of the organisers of the night? That about right?’

Liz rolled her eyes upwards and blew air out of her ruby lipsticked lips. ‘Well you’re not wrong about some of it. Eddie did give us a lift home.’ She leaned forward. ‘But it wasn’t a smoker night. That’s just a load of fanny they tell the council so they can get a licence.’ She furtively glanced around even though the bar was empty. ‘It was a UVF fundraiser.’ Her voice dropped to a whisper as she inclined her head to the side. ‘You know. From across the water.’

Rosie nodded, deadpan, as if she heard this every day. A little nudge of adrenalin in her gut pushed her hangover away. It wasn’t news that the UVF had fundraisers in Glasgow and elsewhere, under the guise of a Rangers football supporters’ night. They were no different from the IRA who ran certain Celtic supporters’ nights, where tins got rattled among the Republican faithful, and all the proceeds went across to the hardmen paramilitaries in Belfast. That was part and parcel of what Glasgow had become – more so in recent years. Even if the truth was that most of the punters spouting sectarian bile could fit their knowledge of Northern Ireland’s bloody history on the back of a fag packet. The fact that they were raising funds here wasn’t a huge story, but nobody from the inside was ever willing, or brave enough, to spill the beans. A barmaid going missing after one of these nights just cranked it up.

‘I gather that they have a few of these fundraisers, but nobody ever talks about it.’ Rosie screwed up her eyes. ‘So who’s this Eddie McGregor then?’

‘He’s UVF,’ Liz whispered. ‘High up. A commander or something.’

Rosie scanned her face, trying to work out why this woman who had shut the door on her yesterday was now singing like a canary, and giving her a rundown of who’s who in the UVF. Either she had a death wish or was already five vodkas in. But she didn’t look drunk. Not by any stretch.

‘Look,’ Liz said, as though she had read Rosie’s mind, ‘I’m not some nutcase, who’s going to fill your head with a load of shite about the UVF. I know stuff. I know what they do. I sometimes hear things in my job.’

‘What kind of things?’

‘Like for instance how they get their money.’ She shrugged. ‘I don’t really give a damn about that.’ She took a mouthful of her drink and raised a hand towards the muffled sound coming from the flute bands as they passed by the bar. ‘In fact I used to walk in the Orange Walk. Most of my life. Born and bred. Queen and country. Rangers fan and Unionist through and through. It’s how we’re brought up here. You’re either Orange or Green. But this is different. There’s something not right about Wendy just disappearing like that.’ She paused, looked Rosie in the eye and half smiled. ‘You a Prod or a Tim?’

Rosie looked back at her, wondering just how loaded the question was. In certain parts of Glasgow you answered that one very carefully, depending on where you were and who was asking. Rosie didn’t feel like giving this complete stranger the lowdown on her spirituality, or how she’d more or less given up organised religion when she woke up to the fact that the Catholic Church had been running it like a multinational organisation, for their own ends. And that she believed all religions were the same – from the Muslims to the Mormons – it was all smoke and mirrors. But she hated the bigotry that ran through the very heart of Scotland, and she despised the way Northern Ireland’s troubles had crept into the terraces at football grounds, turning almost every Old Firm match into a bloodbath.

‘I was brought up a Catholic.’ Rosie decided to be honest. ‘But I’m not really anything now. I have lots of friends of all religions. But I don’t like bigotry.’ She pointed her thumb in the direction of the bands outside. ‘I dislike that walk out there every bit as much as the Hibs walk from the other mob next month. None of them have any place in this country.’ Stuff it, Rosie thought. She called a spade a spade and if it offended Liz’s sensibilities, then so be it.

Liz said nothing for a few seconds, then stubbed her cigarette out.

‘Aye. Fair enough.’ She smiled. ‘At least you’re honest.’

Rosie was relieved, and the iciness between them had been broken. Her mind was a blur of questions and she felt now Liz was ripe for talking. Whether any of it was provable was another story.

‘So, Liz … What do you mean you know how they make their money? You mean from the fundraiser nights?’

‘No. Well. That as well.’ She raised her eyebrows. ‘It’s all drugs. Coke. Ecstasy. They make a fortune from that. The UVF run it big-time in Scotland – mostly Glasgow and the west.’

Saying that Loyalist and Republican gangs were organised, drug-dealing criminals was like revealing that a bear shat in the woods. But Rosie decided to let Liz talk and see where it took them.

‘The UVF run all the coke, you’re saying? How exactly do you mean?’

‘They bring it in. In football buses. In the Rangers supporters’ buses, when they go abroad. Spain, Holland. Germany …’

Rosie hoped her eyes hadn’t lit up.

‘You serious, Liz? You mean on buses when the fans travel to European Cup matches? With ordinary fans?’

Liz nodded. ‘Aye. Most of the fans don’t know anything about it. But I used to go out with a guy who goes on one of the supporters’ buses from the pub I worked in down on London Road. I still see him now and again. I could maybe find out. But they do it in other pubs too.’ She paused. ‘But he told me that Eddie McGregor is the money man. It’s him who goes with the cash for the deals.’

‘You know a lot of stuff about an organisation and a criminal activity that’s supposed to be top secret.’ Rosie tried not to sound sarcastic.

‘Over the years I’ve got to hear a lot.’ She crossed her heavy thighs and glanced down at her chunky wedge sandals. ‘It’s never really mattered to me until now. But something stinks about Wendy going away, and I’ll do anything to find out.’ She paused. ‘Right now I want to know if you and your paper are going to do anything to try to find her.’ She stopped and swallowed. Suddenly her eyes filled up. ‘Wendy didn’t do a runner. I’m telling you that for sure. She had no reason to run away.’

‘Do you think something has happened to her? Is it possible she was mixed up in the drugs and you didn’t know?’ Rosie asked.

‘No, no,’ Liz said quickly, shaking her head. ‘Definitely not. I would know if she was involved in that. But I think something’s happened to her. And I think Eddie knows about it. Okay, I know I’m telling you stuff that could get me done in, and I’m sure the coke runs on the bus have got nothing to do with Wendy’s disappearance. But one thing I feel sure of is that Eddie McGregor is behind her going missing, and I’ve got no other way to get to him than get somebody like you to expose him.’ She shook her head. ‘But I’m terrified just being here, if I’m honest.’

She shook her head and put a hand to her lips, looking vulnerable for the first time, and Rosie watched as she tried to compose herself.

‘Do you think something has happened to her? Have you told the police?’ Rosie asked.

‘I told them some stuff. Like how Eddie drove us home that night. But I didn’t tell them everything.’

Silence.

‘Why not, Liz?’

Silence. Rosie watched her as she wiped tears from the corners of her heavily made-up eyes.

‘Because I thought she would turn up. I didn’t want to do anything that would get them digging around on what the night really was – you know, the UVF fundraiser. I didn’t want to be the one who grassed that up to the police. So I just said Eddie dropped me off, then took Wendy home to her house.’

‘And is that not what happened?’

‘No. Not quite.’ She wiped under her eyes where the mascara had smudged. ‘We went to a flat Eddie uses in the city centre – he keeps the place very quiet, so nobody knows he’s got it. We just had a couple of drinks.’

Rosie nodded.

‘We weren’t drunk. Just tipsy. Then Eddie dropped me off at my flat.’

‘So the only thing you didn’t tell the cops is that you went back to Eddie’s for a drink?’

Liz bit her lip.

‘Well. No.’ She paused. ‘The next day, I got a phone call from Eddie saying to keep it quiet that we were at his for a drink. He said it was because Wendy was going out with Jimmy Dunlop and he didn’t want him to get to know about it. I didn’t tell the cops about that. I tried to phone Wendy all day, but couldn’t get her. I thought she’d be sleeping. Then I was working at night, so I didn’t go round to her house till the next day. There was still no answer. Her mum and dad were away on holiday, so she was in the house by herself. I spoke to Jimmy, and he was upset because he couldn’t get her either. It was only when her parents came home the next day that they called the cops because there was no sign of her anywhere.’

‘Jimmy Dunlop?’ Rosie said, hoping she was remembering all the details. She didn’t want to take a notebook out as the barman kept glancing over at them. ‘Do you know him?’

‘Yeah. He’s UVF too. Wendy told me he was in Belfast last month taking the oath at the Shankill. They’ve been going out for nearly three months. He’s all right, Jimmy. Hard, but a good guy. He’s nuts about Wendy and she’s really into him too. That’s how I know she wouldn’t just up sticks and leave home. She was staying with her ma and da. She’s the only one in the family. She wouldn’t leave them like that.’ Tears came again and she shook her head. ‘Something’s happened to her. I just know it. It’s been a month and we’ve heard nothing. That’s not Wendy.’ She looked at Rosie. ‘Can you help? Can your paper do something?’ She took a tissue out of her pocket and blew her nose.

‘We can write something, Liz. I need to work out exactly what, though. I need to talk to the editor and see what we can do. But maybe you should have told the cops what you’ve told me.’

‘No fucking way. And get my throat cut?’

Rosie took a deep breath.

‘But you’re telling me.’

‘That’s different.’ She looked Rosie in the eye. ‘You won’t tell anybody it was me who told you stuff, will you?’

‘Listen, Liz. Nobody will ever know you talked to me. But you must never tell anyone you spoke to me. It would be dangerous for you if the kind of people we’re dealing with thought you were talking to a reporter. You know that, don’t you?’

‘Don’t worry. I’m not stupid, Rosie. I know I’m taking a risk just sitting here. But I didn’t know what else to do. I didn’t want to go to the cops. Then when you came to my house yesterday, it got me thinking.’

‘Have you told Jimmy Dunlop anything?’

‘No. Nothing.’

‘Would he talk to me?’

Liz shrugged. ‘You could try. He’s not a bad guy. No way is he involved in Wendy’s disappearance though. But he’s a UVF man through and through now.’

‘What about her parents? Would they talk?’

‘No. They haven’t said much. They’re nice people. But I don’t think they’ll know anything.’

Rosie asked for Liz’s mobile number and stored it in her phone.

‘I’ll be in touch in the next couple of days, and we’ll meet again. Meanwhile, say nothing.’

‘I know.’ Liz finished her drink and stood up and looked at her watch. ‘I need to go. I hope you’ll help find Wendy. I don’t care what you do with any of the . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...