- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

How do you kill a Saint?

Falcio, Kest, and Brasti are about to find out, because someone has figured out a way to do it and they've started with a friend.

The Dukes were already looking for ways out of their agreement to put Aline on the throne, but with the Saints turning up dead, rumours are spreading that the Gods themselves oppose her ascension. Now churches are looking to protect themselves by bringing back the military orders of religious soldiers, assassins, and (especially) Inquisitors—a move that could turn the country into a theocracy. The only way Falcio can put a stop to it is by finding the murderer. He has only one clue: a terrifying iron mask which makes the Saints vulnerable by driving them mad. But even if he can find the killer, he'll still have to face him in battle.

And that may be a duel that no swordsman, no matter how skilled, can hope to win.

Release date: April 7, 2016

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 576

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

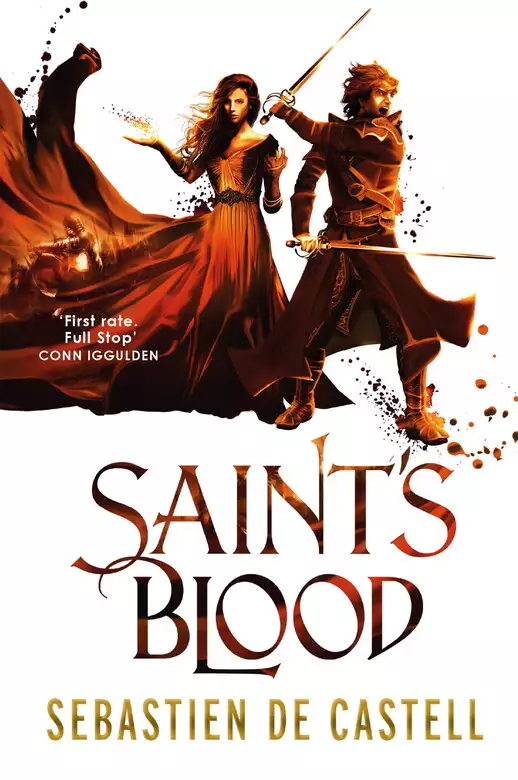

Saint's Blood

Sebastien de Castell

On The Morning Of Your First Duel

On the morning of your first duel, an unusually attractive herald will arrive at your door bearing a sealed note and an encouraging smile. You should trust neither the note nor the smile. Duelling courts long ago figured out that first-time defendants are less prone to running away if it means embarrassing themselves in front of beautiful strangers. The practice might seem deceptive, even insulting, but just remember that you are the idiot who agreed to fight a duel.

Don’t bother opening the envelope. While the letter might start out with extravagant praise for your courage and dignity, it quickly descends into a lengthy description of the punishment for failure to show up at court. In case you’re wondering, the penalty in Tristia for attempted flight from a lawful duel is roughly the same as that of attempted flight from the top of a tall tree with a rope tied around your neck. So just take the unopened envelope from the herald, crumple it in your hands and toss it into the fire. It helps if you do this while uttering a dismissive snort or even a boisterous ‘huzzah!’ for best effect. Then as the flames feast upon the details of your upcoming demise, place your hands on your hips and strike a confident pose.

The herald might, at this point, suggest you put on some clothes.

Choose trousers or breeches made of a light, loose fabric, with plenty of room to move. There’s nothing quite so embarrassing as having your lunge come up short at the precise moment that your enemy is counter-attacking and he drives his blade deep into your belly just as your seams split at the crotch.

‘But wait!’ you say. ‘I haven’t done anything wrong! How did I end up in such dire circumstances when I don’t even know how to hold a sword properly?’

The herald will laugh brightly, as though firmly of the belief that you’re merely jesting, before ushering you out the door and escorting you to the courthouse to meet your secondier.

The law in Tristia, observed in all nine Duchies, requires that every duellist be supported by a second – for otherwise, who would go back and forth between you and your opponent to deliver the necessary scathingly droll insults? If you have no one of your acquaintance willing – or able – to fulfil this sacred duty, and you are too poor to hire a suitable candidate, then you can count on the local Lord or Duke to provide a secondier for you. That’s right: you live in a country so feckless and corrupt that those same nobles who would gladly stand aside as you starve to death would never, ever consider allowing you to be skewered by the pointy end of a blade without a second standing proudly beside you.

Make your way past the twin statues of the Gods of Death and War that guard the double doors leading into the courthouse and through to the large central room littered with exquisite architectural features, none of which you’ll notice, for by now your eyes will be fixed on the duelling court itself. The classical form is a simple white circle, roughly ten yards across, however, in these modern times you may instead find yourself in a pentagon or hexagon or whatever shape is deemed to be most blessed by the Gods in that particular Duchy. Once you’re done admiring the architecture, take a look at the person standing on the opposite side of the duelling court. This is the moment to remember to clench all the muscles in your lower body to prevent any . . . accidents.

Your opponent – likely a highly skilled Knight, or perhaps a foreign mercenary – will smile or grimace, or possibly spit at your feet, and then immediately turn away and pretend to be engaged in a thoroughly witty conversation with a member of the audience. Don’t worry too much about this part – they’re only doing it to unnerve you.

The clerk of the court will now announce the terms of the duel. You might be tempted to take heart when you hear that this duel isn’t to the death, but that would be a mistake. Whichever Lord or Lady you offended has almost certainly instructed their champion to first humiliate you, then bloody you, and finally – and with a grand flourish that will bring the audience to their feet, roaring with applause – kill you.

When this happens, you can rest assured that the presiding magistrate will undoubtedly make a great harrumphing noise over this gross violation of the rules, and will immediately fine said Lord or Lady, although that will be roughly equivalent to the cost of the wine in the goblet they’ll be drinking while watching you bleed out on the floor.

Not really your best day, is it?

Well, that’s for later. For now, take a good, long look at your opponent standing across from you in the duelling court, because this is the part where you learn how to win.

Your enemy is almost certainly a great fencer – someone with speed, strength of arm, exceptional balance, lightning reflexes and nerves of steel. A great fencer spends years studying under the finest masters in the country. You, regrettably, aren’t likely to have had the benefit of any of those fine qualities and there’s a good chance that your only fencing master was your best friend when the pair of you were six years old, play-fighting with sticks and dreaming of growing up to be Greatcoats.

But you don’t need to be a fencer right now; you need to be a duellist.

A duellist doesn’t care about technique. A duellist won’t be walking into that circle hoping to impress the audience or curry favour with their nobles. A duellist cares about one thing only, that most ancient and venerable of axioms: Put the pointy end of the sword into the other guy first.

So as the clerk strikes the bell signalling the beginning of the duel and your opponent begins his masterful display of skill to the appreciative oohs and ahs of the audience, forget about life and death or honour and cowardice; forget about everything except finding that one opportunity – that single moment – when you can push the top three inches of your blade into your opponent’s belly.

In Tristia we have a saying: Deato mendea valus febletta. The Gods give every man a weakness.

Remember this, and you might just survive the day. In fact, over the years that follow, you might even go on to win other duels. You might even become known as one of the deadliest swordfighters of your generation. Of course, if that does turn out to be the case, then it’s equally likely that one day – perhaps even today – that great swordfighter who’s about to lose the duel?

It could be you.

CHAPTER TWO

The Sanguinist

‘You realise you’re losing quite badly, Falcio?’ Brasti asked, leaning against a column just outside the seven-sided duelling court of the Ducal Palace of Baern.

‘Shut up, please,’ I replied.

My opponent, whom I’d been informed was undefeated in court duels but whose name I’d forgotten, gave me a little smirk as he flicked the point of his smallsword underneath the guard of my rapier. I swung my own blade down in a semi-circle to keep him from stabbing my thigh, but at the last instant he evaded my parry by flipping his point back up. He extended his sword arm and pushed off his back leg in a quick lunge. Had there been any justice in the world, he shouldn’t have been able to reach me.

‘Saint Zaghev’s balls,’ I grunted, the tiny cut burning into my right shoulder: a reprimand for misjudging the distance.

Why do I always let myself get tripped up by smallswords?

Despite the name and the delicately thin blade, smallswords are deceptively long. My opponent’s was only a couple of inches shorter than my own rapier, and he’d made up the difference with an extravagantly long lunge of the sort immortalised in the illustrations of the more imaginative fencing manuals.

From the far side of the duelling court Kunciet, Margrave of Gerlac, the rotund, foetid bastard who’d engineered this duel, shouted, ‘Bravasa!’ at his champion. Twenty or so of the Margrave’s retainers joined in the cheer, adding a few sprinkles of ‘Fantisima!’, ‘Dei blessé!’ and other mis-applied fencing terms.

However much this annoyed me, it is accepted practice for a duellist’s supporters to cheer them on – in fact, I was entitled to similar outbursts from my own admirers.

‘This Undriel fellow really is remarkably skilled,’ Kest remarked.

Undriel. That was the bastard’s name.

Brasti came to my defence, after a fashion. ‘It’s not Falcio’s fault. He’s getting old. And slow. Also, I think he might be getting fat. Just look at him – barely four months since he beat Shuran and already he’s half the man he once was.’

Always nice to have friends nearby in troubled times, I thought, batting at Undriel’s blade with a clumsy parry that was testament to my increasing exhaustion.

‘Don’t distract him,’ Ethalia said.

I started to glance over to give her a reassuring smile, but instead felt the heel of my right boot slip on the slick floor and stumbled several steps back, trying to catch my balance.

Idiot! Reassure her by not dying.

Undriel and I circled each other for a few seconds, eyeing each other for signs of any growing weaknesses that could be exploited.

Gods, but I’m tired. Why doesn’t he look tired?

The sound of someone sipping tea drew everyone’s attention: Ossia, the rake-thin, elegantly aged Duchess of Baern was sitting upon her high-backed throne at the head of the courtroom. Aline, heir to the Crown of Tristia, and Valiana, Realm’s Protector, sat on either side, perched on considerably smaller chairs, like children made to attend their aunt. Aline periodically looked up at the Duchess in irritation, but Valiana’s barely contained fury was reserved entirely for me.

I couldn’t really blame her.

What had started as a largely ceremonial event meant to introduce Aline to the various minor nobles of the Duchy had taken an unexpected turn when the Margrave of Gerlac, one of six men hoping to replace the ageing and childless Duchess Ossia, took advantage of our presence to launch a legal dispute against the Crown. Through a torturous process of twisted judicial logic, he’d claimed he’d merged his properties with those of the churches on his lands and thus was now – despite still occupying those lands – exempt from paying taxes. He’d even brought in a few token clerics in impressively ornate robes to confirm his story.

Duchess Ossia, ever the diplomat, had elected to defer judgement of the issue to Valiana, who, as Realm’s Protector, had patiently listened to every argument, reviewed every document and then promptly declared the case invalid. Kunciet, as such men do on those rare occasions when they don’t get their way, threw a hissy fit. He began by questioning the validity of the verdict, then Valiana’s standing as Realm’s Protector and then, right in front of us, started making not-very-subtle threats against Aline.

That was when I took over.

Less than six months ago I’d bled buckets to keep Shuran and his Black Tabards from taking over the damned country. I’d risked not just my own life but those of the people I loved best to save those same Dukes who’d been spending a considerable portion of their spare time trying to have me killed. I’d been beaten, tortured and brought to the very edge of death, and all of it so that the daughter of my King could one day take her rightful place on the throne.

Did anyone seriously believe that I was going to let some noxious back-water nobleman like Kunciet make public threats against her?

The hells for that.

Undriel made a rather stunning and unexpected dive below my blade, rolling on the ground and coming up on my left side, then skipping away before I could cut him. In the process, he tagged me again, this time on my left shoulder.

‘Should’ve worn your coat, Falcio,’ Brasti said.

‘Shut up,’ I repeated.

Armour is forbidden in judicial duels, but most legal interpretations limit the prohibition to chainmail or plate. Since our greatcoats are made of leather, albeit with bone plates sewn inside, they’ve never been considered armour, not in the technical sense. After all, that was part of the design consideration behind the coats in the first place.

So why wasn’t I wearing mine? Because Kunciet, Margrave of Gerlac, had declared such protection ‘cowardly’, and because Kest had, through a combination of raised eyebrows and light coughs, apparently agreed with him. In other words, because I’m an idiot and my friends are trying to kill me.

A line of red began to stain the left shoulder of my white linen shirt, an almost perfect match to the one on my right. Evidently Undriel was using me as a canvas and wanted to balance his composition.

The son of a bitch is trying to bleed me to death.

Undriel is what we call in the duelling business a sanguinist: a fencer whose primary strategy is to go for little cuts – wounds that sting and bleed and distract you, until you start to slow down without even realising it. Sanguinists take their time, pulling you apart bit by bit, until they can end the fight with a single, brilliant flourish – they usually go for an artery so that you end by bleeding out spectacularly all over the floor. It can create quite a stunning tableau for the audience.

I hate sanguinists.

The wounds themselves were more annoying than anything else. Later, assuming I didn’t die, Ethalia would use one of her almost magical ointments to treat the wound, followed by a sticky salve to seal it. One of the many reasons I should already have asked her to marry me was the gentle way she’d pass her finger over the wound to wipe away the extra salve. That experience was so oddly sensuous it almost made you think getting a few more cuts wouldn’t be so bad . . .

I let out an inadvertent and embarrassingly high-pitched yelp as the tip of Undriel’s blade scored another nick, this time on the left side of my jaw.

Focus, idiot. He’s doing a fine job of bleeding you without your help.

Undriel pressed his advantage in a whirling attack, moving the point of his blade in a figure-eight motion, then suddenly striking out towards me like a snake, only to pull back the instant I tried to parry him.

Dashini, I thought suddenly, barely able to keep myself from fleeing the duelling circle. He’s using Dashini tactics.

Undriel caught the look of fear on my face and, smiling, increased the speed and ferocity of his attack. I swung my own blade in a clumsy counter-pattern to keep him from getting too close, but my heavier weapon made it a tiring exercise on my part. I was sweating now, and not just from exertion.

Stop being a fool! The Dashini are dead, and even if they weren’t, there’s no way this prancing pony is one of them. He’s just practised their style to throw you off-guard.

‘So it’s true, what I’ve heard about you,’ Undriel said. It was the first time he’d spoken and his voice was as relaxed as if he’d just got out of bed.

‘If what you’ve heard is that I’m going to knock you on your arse so hard you won’t be able to sit a horse for a year, then yes, it’s all true.’ My bravado would have sounded more convincing had my lungs not been pumping like a bellows.

‘Rumour has it that since the Lament you wake up screaming every night, begging for the torment to stop.’

‘I wouldn’t know,’ I said. ‘I’ve been having quite a lot of sex lately so I’m usually too tired to remember my dreams.’

Why did I say that? I sound like an idiot. Gods, what did Ethalia do to deserve me?

I swung my rapier in a low arc with enough force to smash the bones in Undriel’s knee, but he skipped out of its path with the easy grace of a dancer before repeating the Dashini pattern that was so unnerving me.

Why was I letting him get to me? More to the point, how was he so good at doing it?

Pieces of a puzzle started to form in my mind: Undriel was intentionally stretching the duel out for far too long. Normally this wouldn’t have been a problem, except that I still tired quickly, the result of the injuries I’d suffered months before. He’d chosen a smallsword, but for the past several years I’d been facing Knights and soldiers who used heavier – and slower – weapons, like warswords and maces. And the Dashini forms, even though they might not be particularly effective when performed with a smallsword, were making me jumpy and clumsy. In other words, he was the perfect opponent to put against me. So what were the odds that Kunciet just happened to have a champion at hand who just happened to incorporate all these disparate tactics into one unique style?

The bastard’s been training for this very fight.

Undriel grinned as if my thoughts were written across my face and came straight for me, and as I stumbled back, struggling to keep out of the way of his swift, dancing attack, the rest of the pieces fell into place. Kunciet hadn’t lost his temper today. He didn’t care about his damned taxes. This whole case had been nothing more than a pretext for him to pick a fight with the Crown and trick me into accepting an unnecessary duel.

What better way to make your bid to become the next Duke of Baern than by killing off a Greatcoat and defying the Realm’s Protector in front of your fellows, all without breaking a single one of the King’s Laws?

Better yet, Kunciet was doing it right in front of the current Duchess – a known ally of the heir – while she sat powerless to stop it.

That’s how you stake your claim to a Dukedom.

In fact, there was only one way he could possibly make an even stronger case: don’t kill just any Greatcoat, kill the future Queen’s favourite. Kill the First Cantor.

That was me, by the way.

Undriel’s smile widened: all the little cuts were starting to slow me down. A single thought went through my head: I swear, I used to be good at this.

CHAPTER THREE

The Lark’s Pirouette

I once asked a doctor why it was that time seems to slow down at the exact moment someone is about to kill you. He told me that during moments of extreme danger, a certain organ in the body begins to excrete a fluid called the ‘vital humour’ which increases strength in the limbs and speeds up the body’s reactions. This has the effect of making it appear as if time itself has frozen, thus giving the soon-to-be-departed one last chance at survival.

One would think such a miraculous fluid would also focus the mind exclusively on the source of danger, but in my case it had the opposite effect. Even with the point of Undriel’s smallsword darting at me, forcing me backwards and keeping me off-balance as he set me up for the final kill, I couldn’t help but notice all the little things going on around me.

Brasti’s eyes were narrowed in confusion, which told me that he was only now figuring out that I was actually in trouble. Kest’s mouth was open, just a hair’s-breadth, as if he’d been about to call out some obscure fencing tactic that might save me, only to realise there wasn’t time. I could even see Valiana’s hand twitch as though she were about to draw her sword and run to my defence. Ethalia, the woman I loved, the woman to whom I’d jokingly said, ‘You might as well stick around. This whole silly business will be done in a minute or two!’, looked as pale as the dead.

Why hadn’t I asked her to leave the courtroom? Why did I accept the damned challenge in the first place? The second we’d arrived in the south I should have picked Ethalia up into my arms, found the nearest boat and set sail for that tiny island she’d told me about a hundred times.

With a doomed man’s fervour I beat back Undriel’s blade and lunged, once, twice, thrice, each time sure I’d found an opening in his defence, each time proven wrong by his effortless parry, swiftly followed by another light cut to my arm or thigh or chest. I was using up my last reserves of strength just to stay in the fight.

It wasn’t enough.

From the corner of my eye I saw Kunciet lean forward, wearing the patient smile of a man who has spent years tending a garden and is now watching the first rose bloom. His retainers began patting each other on the back. Ossia, Duchess of Baern, looked disappointed.

Well, I’m disappointed too, your Grace. I was about to lose, and everyone knew it – everyone except Aline. Unlike the others, she watched me impassively, without the slightest widening of the eyes or trembling of the lips, as my opponent worked me like a puppet around the duelling circle.

She doesn’t see what’s happening, I realised, horrified. She’s seen me fight Knights and bully boys and even Dashini assassins and now she thinks I can’t be beaten.

That’s the problem with people who aren’t duellists: they don’t understand that eventually, everyone loses.

The vaguely metallic taste on my tongue – I’d bitten my own lip – brought me back to the fight. No. I won’t die like this, not in front of the people I love. I swear, all you worthless Gods and Saints, I’m going to find a way to win, and then, after a suitable convalescence, I’m asking Ethalia to marry me.

Undriel, no doubt promised a huge reward if he killed me, was ready to perform his grand finale. He delivered a quick cut against my right wrist – not deep, but enough to make me loosen my grip on my rapier – and followed up with a sudden hard beat of his sword’s crossbar against my blade, sending my rapier flying up into the air above me.

I started to reach out with my left hand in a desperate attempt to grab the hilt as Undriel prepared a high slash meant to sever the artery in my neck. A thrust to the chest would have been a surer target, but it would have lacked the more artistic final flourish of a blood spray.

Arrogant bastard.

I kicked out at his knee, which he shifted out of reach, but that distraction gave me a precious moment to catch my falling rapier in my left hand even as Undriel scored another, deeper, cut against my right forearm. I could already feel it going numb from the pain.

Great, now I’m going to have to fight left-handed.

Having been deprived of his first attempt at a spectacularly stylish kill, Undriel dropped the guard of his weapon low and brought the blade straight up in a vertical line.

A lark’s pirouette? He’s going to end me with a fucking lark’s pirouette!

The flowery name masks a deadly and precarious technique. The attacker leaps past his opponent, whirling his blade in the process – not to slash, but to parry the counter-attack as he comes around the other side. He completes the move by landing in a perfect reverse-lunge, his rear foot and arm thrown back as the tip of his sword drives deep into his victim’s kidney.

The lark’s pirouette is devastating to behold: it’s what you do when you want to show the world that you’re a true master of the blade – but it’s a move you use only when you’re absolutely sure that your opponent has exhausted all his strength. Undriel could have killed me any number of simple, clean ways, but he wanted to break me first.

That realisation sent a surge of anger through me. Death I could have lived with – but this? You come here to humiliate the Greatcoats, to threaten the girl I’ve sworn to put on the throne, and you want to make a performance of it? You forgot the first rule of the sword, you son of a bitch.

I fought the instinct to fall back and instead did something Kest and I used to practise as boys: I counter-windmilled into Undriel’s blade. As he spun clockwise while leaping past me, I turned the other way, letting him knock my point out of the way even as I readied my free right hand to grab his blade. It was an outlandish, desperate tactic, but I was, at that moment, an outlandish, desperate man.

As we moved around each other like dancers on a stage, Undriel, suspecting what I was doing, began to pull his weapon away before I could get a solid grip on it, cutting into the palm of my hand in the process – of course, this is why most masters tell you never to counter a lark’s pirouette this way. That’s why the second part of my manoeuvre was to toss my own sword on the floor right between my opponent’s legs as he was spinning. The hilt clattered against the marble and the blade became caught between Undriel’s left calf and his right thigh, entangling his feet. He was already midway through his turn and it was too late for him to catch his balance. His eyes caught mine and went wide.

It was my turn to smile.

I stepped into him, bending my knees for leverage and holding his blade tightly in my bleeding right hand as I pressed my left against his chest and shoved with every last ounce of strength that remained in my limbs.

Undriel fell backwards, his feet still caught in my blade, his attempts to regain his balance only making his situation worse. His desperate stumbling took him all the way outside the circle until he bashed the back of his head against one of the marble columns ringing the duelling court.

A satisfying crack echoed throughout the room, followed by the heart-warming sight of Undriel sliding, ever so slowly, down the length of the column until his bottom hit the floor with a loud thump. The blow to his head wouldn’t be enough to kill him, but it was more than sufficient to draw a collective wince from the audience, followed soon thereafter by peals of laughter.

I took the deepest breath I could manage and let myself drop to my knees. I had, by the skin of my teeth, not only evaded a humiliating death that would have embarrassed the Crown and called into question the vaunted abilities of the Greatcoats, I had even defeated the Margrave’s champion without killing him – and I’d done it in a way that would leave people believing I was the superior swordsman and had simply been playing along until it no longer amused me.

All of that would have been extremely gratifying, if only I wasn’t absolutely positive that Undriel was better than I was. I had eked out the narrowest possible victory thanks to a childhood trick and an unexpected stroke of luck. Without those things, I would have been dead.

My name is Falcio val Mond, First Cantor of the King’s Greatcoats. Not long ago I was one of the finest swordsmen in the world.

These days? Not so much.

CHAPTER FOUR

The Healers

The funny thing about a duel is how little attention is paid to the opponents after it’s over. Once one man drops, what follows is a furore of activity as audience members pay up or try to slip out before their creditors can catch up with them. Some cheer and boast of their predictions as if they themselves had fought the duel while others gripe and spitt in their cups over the poor performances of the duellists.

And this is the point when the opponents, only now realising just how badly they’ve been hurt, let forth a wide variety of moaning sounds as they crawl towards anything that looks remotely like a chair. Doctors or priests (depending on which is more urgently required) rush in to begin their work, but what I want most in those moments is for Ethalia to come and treat my wounds. However, the duellist for the Crown is always examined first by the royal physician, a heavyset man of middle years named Histus with whom I shared exactly one thing: we both hated him having to treat me.

‘Are you sure you won this duel?’ he muttered as he began prodding at my wounds.

I flinched. ‘Are you sure you don’t work for the other guys?’

He brought out a flask of cleansing alcohol and poured it liberally over the cuts. ‘You know, I’m going to end up amputating one of your limbs if you keep this up.’

‘My wounds aren’t infected.’

‘I never said it would be on medical grounds.’

I glanced over at Undriel, lying on the floor next to one of the columns. Usually there’s a sort of bond that forms between duellists when neither has ended up dead. I didn’t expect that to be the case this time.

A number of Kunciet’s retainers – notably, not the Margrave of Gerlac himself – were standing over Undriel, making noises of great concern, although not, as I might have expected, in reference to his personal wellbeing. Instead, I heard, ‘Do you think he’ll ever be a champion again?’ answered with, ‘Can’t see how, not after that beating.’ This was followed by sage comments such as, ‘Lost his touch, he has. Knew it the second I saw him enter the court.’

Maybe I was wrong about not feeling a shared bond.

Kunciet was busying himself with a different tradition: the one in which the losing plaintiff immediately starts hurling accusations of foul play and cheating. He launched into a steady stream of denouncements that began with the ungentlemanly conduct on my part (laying a hand on an opponent during a duel? Improper!) and followed up with a charge that the duelling circle was not perfectly circular, descending into a rather convoluted accusation of dark sorcery involving Valiana, Aline, Kest, Brasti and me performing some rather daring feats of sexual prowess as part of a ritual dedicated to Saint Zaghev-who-sings-for-tears.

The clerics, no doubt worrying that their financial arrangement with the Margrave was about to become null and void, were vigorously backing him up.

I thought about challenging the fat bastard then and there, until I realised even he could probably take me down at that precise moment. Fortunately, there was someone in the room even angrier than me.

‘One more word from you, Margrave,’ Valiana said, her voice as cold as the North Wind, ‘especially one word aimed at the heir to the throne of Tristia, and I swear it will b

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...