- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

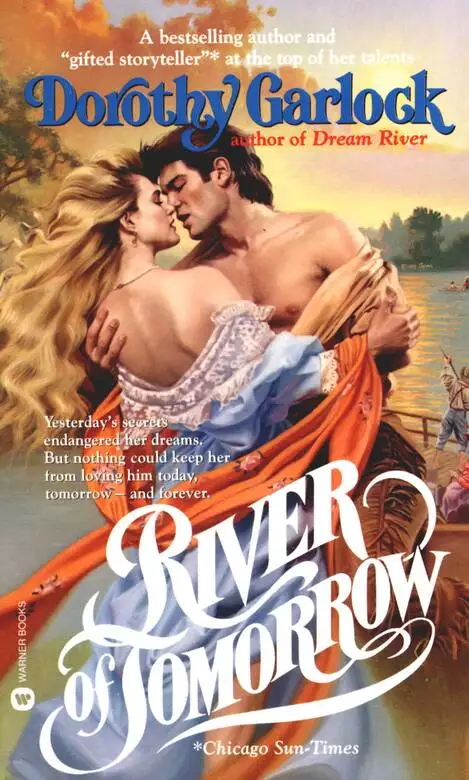

The bestselling author of Lonesome River and Dream River creates her most compelling love story to date. In this final novel of the Wabash Trilogy, a bold young woman must overcome the harsh reality of the frontier before she can dare to love.

Release date: April 12, 2001

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

River of Tomorrow

Dorothy Garlock

His hand slid across Mercy’s back beneath her hair and he wrapped her in his arms. He gathered her to him as gently, carefully, as if she were the most fragile thing in the world.

In a daze of joy Mercy clung to him. She wondered if he loved her as a woman or if he was fond of her because she was his foster Sister. Did she only imagine she felt his lips nuzzling her ear? In the warmth of his embrace, she longed to whisper that the love she felt for him was the all-consuming love of a woman for her man. She wanted to tell him to please take her as his mate, to join his body with hers, to plant seeds of his children in her womb. What would he say? Would he be shocked? Disgusted by her boldness?

Her words came in a quivering voice. “I can’t imagine life without you . . .”

Critics love Dorothy Garlock’s Wabash Trilogy:

BOOK I–LONESOME RIVER and BOOK II—DREAM RIVER

“A sprawling, gutsy saga . . . the Wabash trilogy promises to continue a career of shining triumphs.”

—Ann’s World, Hearst Cablevision

“Vivid and real . . . there is joy, laughter, sadness, and tears in these pages . . . a gripping, endearing, and exciting read that is full of surprises and written in Garlock’s own magical style.”

—Affaire de Coeur

“Again and again in compelling love stories, Dorothy Garlock writes of unforgettable characters who tamed the frontier.”

—Romantic Times

Also by

Dorothy Garlock

Annie Lash

Restless Wind

Wayward Wind

Wild Sweet Wilderness

Wind of Promise

Lonesome River

Dream River

To special people—

Candace Camp,

Pete Hopcus,

and Stacy—

with special love.

Mercy cast an uneasy glance over her shoulder. It was silly, she knew, to be so jumpy about going home to an empty house, but the two men who had loitered across the road from the school for a good part of the afternoon bothered her. When at first she had glanced out the window and seen them there, she hadn’t thought much about them. Then later, in the middle of the afternoon, she noticed they had moved to the edge of the woods across from the school and had built a fire. Were they camping there? It was far too early to build a supper fire. The men were still sitting by the fire when the school day ended and Mercy dismissed the children, but when she left the school to walk the mile home, they were gone.

Travelers constantly passed through Quill’s Station on their way to or from Vincennes, the city that had been established by the French almost a hundred years ago in 1732. Quill’s Station, on the banks of the Wabash, sat astride the direct route to the city. The village of more than one hundred people, surrounded by rich timber and grassland, stretched along the river road.

With her shawl hugged to her, Mercy walked briskly down the well-packed dirt road. She called a greeting to Mike Hartman when he came out onto the porch of the store, owned by Mike and Mercy’s father, with several coils of rope over his shoulder. She nodded to the father of one of her students who was passing in a two-wheeled cart.

As she passed Granny Halpen’s rooming house, she waved to the elderly woman, who sat in her rocking chair on the porch, a quilt across her knees to ward off the chill, a snuff stick in the corner of her mouth. Granny knew everyone and everything that went on in Quill’s Station. Farrway Quill had once said that the village had no need for a newspaper when it had Granny.

The houses in the town, no more than two dozen, were hewn timber set upright in the ground and chinked with stone and mortar. Except for the Quill house, none was more than one story high. All had porches on at least two sides, some on three. Surrounding each was a garden and fruit trees. Most of the houses were evenly spaced on long, narrow tracts of land and were set close to the road.

The Quill house, the largest and by far the grandest house in town, was on the bend of the road at the far end of town. As Mercy walked up the path from the road to the white, two-storied house with its massive stone chimneys, she thought how empty and desolate it seemed without lamplight shining from its windows. A sudden yearning to see Mary Elizabeth and Zack running to meet her, and her mother waiting for her in the doorway, sliced through Mercy so acutely that tears filled her eyes.

Inside the house, she lit the lamps to disperse the gloom. It looked different somehow—big, lonely. The fire in the fireplace had been banked. All Mercy had to do was rake aside the ashes and add kindling from the wood box, then a larger piece of wood. She did this now, squatting, holding her skirts up over her knees to keep them from being soiled. Soon the cheery blaze was sending warmth into the room. She removed her shawl and hung it over the back of the chair.

Darkness had brought a lively wind from the northwest. Mercy listened to it scurrying around the corner of the house, worrying a limb of the walnut tree and causing it to rub against the roof, making a scratching sound she easily identified. Now the brisk March wind was beginning to find its way down the chimney of the huge cobblestoned fireplace, teasing the flames, flattening them so that sparks came out of the burning wood, then dancing back up the chimney.

Curled up in the big chair where Papa Farr usually sat in the evenings, Mercy watched the flames and wondered what her life would have been like if he had not found her in the cellar of a burned-out homestead down in Kentucky and brought her here. She remembered someone saying that Farrway Quill had a habit of gathering up orphans. On the same trip he had found Liberty and her family stranded on the river road, and Daniel Phelps, the only survivor of a train of settlers who had been ambushed by river pirates. He had fetched them home, married Liberty, and together they had become a family. Daniel and Mercy had been as much a part of the family as Farr and Liberty’s own children, Zack and Mary Elizabeth. Mercy liked to think that her real parents would have been people just like Farr and Liberty Quill.

* * *

“I’ll be all right, Mamma,” Mercy had said only that morning when Liberty and the children were preparing to leave Quill’s Station to join Farrway, who was serving as a congressman in Vandalia, the capital of Illinois. He had been chosen in the fall election to represent his district, and he wanted his family with him.

“Eleanor and Tennessee will be back from Vincennes in a couple of days, and Tennessee will stay with you until school is out. Then you’re to come on to Vandalia,” Liberty had told Mercy as she gave her a parting hug.

Tennessee Hoffman, the daughter of the French postmaster of Davidsonville in Arkansas Territory had been brought to Quill’s Station by Gavin McCourtney and his wife, Eleanor, when they came to buy the sawmill from Farrway Quill. The childless couple were very fond of the French-and-Indian girl who was a few years older than Mercy.

Although Mercy was half a head taller than the woman who had raised her, Liberty and she could be taken for real mother and daughter. Both were blond and blue-eyed. They were not tall, but they were slender and graceful, and each had a beautiful mouth, whether laughing, talking, or in repose. They were totally feminine women, fragile to look upon, but with wills of iron.

“Did Daniel say he would take me?” Mercy had asked.

“He said that he would make sure you had a reliable escort. I’ll not worry about you one bit as long as Daniel is here to look after you. He always has, you know.”

“Too much!” Mercy had retorted spiritedly, because she was afraid she would cry. “He finds something wrong with every man who comes courting me and reports it to Papa. If he doesn’t let up, I’ll soon be an old maid.”

“An old maid at nineteen?” Liberty had scoffed. “It’s 1830, dear. Girls don’t marry as young as they did in my day. And besides, I don’t think you’ve really liked any of the men who have come calling.”

“I haven’t,” Mercy admitted with a shy smile. “But, Mamma, I told you what Daniel did at the Humphrey barn dance. He hit Walt Cash because his hand slipped down to my bottom while we were dancing. Walt meant no harm. He had been drinking. Daniel should control his temper.”

“His temper? He said Walt was acting improperly.”

“Walt is only a boy of eighteen, even if he is big as an ox, and Daniel is a twenty-five-year-old man. Since he built his own house, he hardly ever talks to me. He just stands around, silent as a tree stump, then he orders me to do this or do that.”

Liberty laughed. “He’s been doing that since he was a boy. Now he has all that wheat land west of us, and with Farr being busy in Vandalia, he has the responsibility of the farm and the mill, not to mention our most valuable asset—you.”

“Oh, damn, Mamma! I’m just being cranky. I’ll miss you!”

“Don’t swear, dear. I’ll miss you too!”

* * *

Above the ticking of the mantel clock, Mercy heard another noise. It was not the tree scraping on the roof or the creaking of timbers. It came from outside the door. She sat quietly, her ears alerted anxiously for a repetition of the sound. Daniel was going to stop by on his way home, but it was too early for him. He would be busy at the mill for another hour. Old Jeems would have done the outside chores and gone back to his cabin in the woods hours ago. The freed Negro hated to be out after dark.

The sound came again, a barely audible scratching at the door. Mercy came to her feet and reached for the pistol that lay on the mantel. She stood holding her breath, her eyes fastened on the door.

The sound was repeated, followed by a throaty “Meoow!”

It sounded like a cat. The only cat that had been in the house was Mary Elizabeth’s cat, Blackbird, and he had disappeared months ago.

Mercy’s mind went wild. Robbers had learned from the Indians to imitate a turkey or some other fowl to decoy a victim. She had never heard of one imitating a cat. Yet was it a cat on the other side of the door, or someone who knew she was here alone, using a trick to get her to open the door? She had to know. Her feet felt like lead. This is stupid, she thought, and willed her legs to move. Why in tarnation was she so jumpy? Was it because she had never before been alone in the house at night?

By the time she reached the door, her fingers were sweating on the pistol. Silently she lifted the door bar and lowered it into the holder. There was no sound. She could hear her heartbeat vibrate into the wood where she pressed her ear. Another “Me-oow” came from the other side of the thick panel. As she cautiously eased the door open an inch, a loud purring began. She pulled the door open wider and looked down. Out of the darkness came the eerie glint of eyes. Relief made her feel foolishly weak.

“Blackbird!” Mercy swung the door back. “Blackbird, where in the world have you been all this time?”

The cat seemed larger than she remembered. She could see that even in the shadows where he paused, taking his time about entering. He purred, moved, tilted his head to look at her, sweeping the floor with his majestic tail.

“Are you coming in or not?” Mercy asked with a laugh. “Oh, I wish you had come yesterday. Mary Elizabeth would have been so glad to see you. She cried, you know, when you couldn’t be found.”

The huge animal finally moved across the threshold, and Mercy closed the door. He walked to the hearth, seated himself, and stared up at her with his slanting, yellow eyes, then lifted a paw and flicked it daintily with a pink tongue. He was as black as night, tall and rangy, with ears ragged from many battles. When he had been little more than a kitten, Mary Elizabeth had caught him with a small blackbird in his mouth. She had named him Blackbird to remind him of the dastardly deed.

“Me-oow,” he said, and began washing his face in earnest.

“I suppose you’re hungry.”

The cat stopped licking and looked at her.

Mercy placed the pistol on the mantel and went to the kitchen, knowing the big tom followed her. She put a biscuit in a wooden trencher and spooned meat drippings over it, set it on the floor, and looked at the cat. He looked back at her, made his way to it leisurely, smelled it, then began to eat daintily.

“Don’t think I’m bribing you to get you to stay,” Mercy said sternly. “You’ll work for your keep, or else you’ll—”

The loud, determined rap on the door cut off her threat to the cat. The knocking came again before she could take a breath. Who would knock like that? Not Daniel. He would open the door and call out her name. Open the door! She remembered she had neglected to drop the bar in place when she let in the cat.

The heavy oak door shook from the force of the pounding as Mercy hurried from the kitchen. She had almost reached the door when it was flung open with such force that it bounced back against the wall. The cold wind swept past her to the hearth, sending a shower of sparks up the chimney. Two men stood before her, blurred against the darkness. Her first thought was that they meant to harm her; otherwise they would have waited for her to come to the door. Her second thought was the pistol on the mantel. She ran toward it but was caught from behind by arms that pulled her tightly up against a man’s chest.

She heard the door slam shut.

“We ain’t goin’ ta hurt ya none, if’n ya behave. We want ta look at ya, is all.” The man spoke close to her ear, then turned her around and pushed her up against the wall.

Mercy could smell their unwashed bodies before her eyes focused so that she could see them. They wore round-brimmed, peaked leather hats pulled down over shaggy, straw-colored hair, that contrasted sharply with the black beards on their faces. Over homespun shirts that were dirty and ragged, with sleeves much too short for their long arms, they wore sleeveless vests of cowhide. Powder horns and shot bags hung from their shoulders by leather straps. The younger man, the one with the short fuzzy beard, held both the muskets. As Mercy’s Frightened eyes met his, his wide mouth twisted into a grin, showing large square teeth.

“By granny, Lenny! She’s sightly. I do be swearin’ it.”

“Who . . . are . . . you?” Mercy’s voice came out heavily, and she spaced the words because she was breathless with fright.

“She’s purty as a button.”

Mercy’s eyes moved from one man to the other. “You’d better get out of here. My brother will be here any minute. He’ll shoot you—”

“She got the mole, Len. I’ll be dogfetched if’n we ain’t done gone ’n’ found ’er.”

The man called Len said nothing. His eyes narrowed as he thrust his face close to Mercy’s, scanning her every feature from the soft blond hair held in a loose knot at the back of her neck to the delicate oval of her face, her wide-spaced, sky-blue eyes beneath curved brows, and her generous mouth. He pinched her chin with rough fingers and turned her face to the light, so that he could see the small mole among the thick fringe of gold-tipped lashes on her lower eyelid.

Mercy jerked her chin from his grasp. Fear pounded over her, making her tongue thick in her mouth and her stomach feel like a slab of rock.

“Get out of here!” she choked. “Daniel will tear you apart if he catches you here!”

“Hush yore blabberin’.” Lenny spoke sharply, the words coming through tobacco-stained lips.

“Ya ain’t ort to rile Len,” the second man told her. “He kin be meaner ’n a ruttin’ moose when he gets his dander up.” He looked about the room. “Lordy! Ain’t this a fancy place? Lookit them shiny floors ’n’ them glass lamps. Hit’s light as day in here, Lenny. I’d shore like Maw ta see it.” He sidled over to the kitchen doorway and looked in. “By jinks, damn! They got one a them cook stoves like we seen in the picture—”

“We ain’t here ta sightsee, Bernie. Let’s get on with what we come fer.”

Bernie stood in front of Mercy, the twisted grin distorting his face. He fingered a strand of her hair. She glared at him, refusing to jerk her head away.

“Yep, she’s purty as a speckled pup.”

“Air ya the schoolmarm what’s called . . . Mercy?” Len asked.

“You know I am. I saw you camped across from the school today. What do you want with me?”

“Have ya got a brown spot on yore butt ’bout this big?” He made a circle with his thumb and forefinger and held it up in front of Mercy’s face.

She drew in a deep, shocked breath as her eyes shot to the door. Her mind raced frantically with ways to escape. But her common sense told her it was useless. Daniel! Please come!

“She’d not know, Len. How’d she see it lessen she put her head ’tween her legs ’n’ looked up? Haw, haw, haw!” Bernie’s laugh was loud and coarse. He leaned the muskets against the wall. “She ain’t goin’ ta tell us, ’n’ we ain’t goin’ to know ’less we take us a look.”

Mercy’s mind was blotted with a heavy cloud of fear, but in a back-of-mind way a thought raced to her brain. They knew who she was—or thought they did. Oh, God! she prayed, don’t let them be my real kin!

Almost before she could complete the thought, Len grabbed her, knelt down, and bent her over his knee. The surprise attack held Mercy dumb and motionless. Her skirts were thrown up over her head, and she felt rough hands pawing at her underdrawers. Panic forced a scream from her throat. She screamed again before a hand clamped over her mouth. Almost mad with fear, she kicked and bucked with all her strength.

“Be still!” A heavy hand came down on her bottom with a sharp slap. “By Jehoshaphat! I’ll be hornswoggled if she ain’t a Baxter! She got the Baxter mark on her ass like Ma said. Lenny, we done found little Hester!”

“I knowed it! She’s sightly, like Maw’s side, ’n’ she got the mark, like on Paw’s side.”

Mercy was not aware of the reason the hand was suddenly torn from her mouth and she was thrown to the floor, or why the table went crashing, or the cat screeched and ran over her back to get out of the way. For a second she was stunned; then, in desperation, she rolled away from the tramping of heavy boots and righted herself so she could see.

Daniel had hit Lenny in the mouth with a rock-hard fist, sending him sprawling against the table. Blood sprayed down over Lenny’s shirt. Bernie, screeching like a wildcat, jumped on Daniel’s back, wrapped his legs around his middle, and threw his arms about his head.

“I got ’em! I got ’em! Hit ’em, Lenny,” he yelled.

Lenny got to his feet on unsteady legs, shaking his shaggy head to clear it.

Daniel, taking a step back toward the heavy oak door, reached up and grabbed a handful of Bernie’s hair. Using it as a handle, he whacked his head sharply against the edge of the door. Bernie immediately went limp and fell to the floor in time for Daniel to meet Lenny’s charge, that carried them both out the door.

Mercy scrambled to her feet and ran to the mantel for the pistol. On the way she stumbled over the cat, who screeched and hissed and ran with tail straight in the air. By the time her frantic fingers found the pistol, Bernie was on his knees, his head hanging between his arms. When he attempted to get to his feet, Mercy moved over and whacked him on the back of the head with the gun barrel. He sprawled facedown on the floor. She waited a moment, and when he remained still, she ran to the doorway.

With the tip of his knife in Lenny’s back, Daniel was urging him up the steps of the porch. Mercy stepped back out of the doorway, and the two men came into the light. Daniel’s eyes went to the man on the floor, then to Mercy.

“You all right?” He had a cut on his cheek, his shirt was torn, and he had a look of cold fury on his face.

Mercy nodded. She was trembling from head to foot. The pistol she held out at arm’s length wavered as if she hadn’t the strength to hold it. Daniel put his knife in his belt and gently lowered her arm until the barrel pointed to the floor, never taking his cold eyes from Lenny’s face.

“I ought to blow your goddamn head off!” His voice was quiet and deadly, his face dark with a fury Mercy had never seen.

“We warn’t hurtin’ ’er. We came ta fetch ’er home.”

“Fetch her . . . home?” Daniel’s eyes went to Mercy’s white face, then back to the man who had spoken the shocking words. “What the hell are you talking about?”

“She’s little Hester, what was took from us down on the Green in Kaintuck.”

“How do you know that? You stupid son of a bitch! Stay away from her if you want to keep that mangy hide in place.”

“We ain’t goin’ ta do that. Maw said fetch her if’n she had the Baxter mark on her butt. It’s thar, right where Maw said it was. She’s got the mole too. Me ’n’ Bernie got ta take her home.”

Daniel grabbed the front of Lenny’s shirt and shook him. “I should kill you for putting your hands on her!”

“How else was we gonna know? She warn’t goin’ ta tell us if’n she had the mark.”

“She’s not the woman you’re looking for, damn you! Her people were all killed. Farrway Quill found her. Now get the hell out of here and take that dog meat with you.” Daniel jerked his head toward the man groaning on the floor.

“Hester’d been stayin’ with kinfolk while Maw had another youngun,” Lenny said stubbornly. “When Paw went to fetch her, he found all our kin thar was dead, but Hester warn’t among ’em. We heard ’bout this here light-headed woman livin’ here with the high mucks. Peddler man said she come here ’bout the time Hester was took by them what killed our kin.”

“Are you accusing Farr Quill of killing your kin and taking your Sister?” Daniel asked quietly.

Lenny put his hands on his hips and jutted his chin forward. “Wal, it shore do look like he done it, ’cause she’s Hester.”

Daniel struck out suddenly and viciously. A knotted fist flattened Lenny’s lips against his teeth, and at the same time another fist grabbed him and slammed him back against the door. While his legs were melting under him, another fist connected with his nose, and Lenny slumped to the floor.

Mercy could see murder in Daniel’s eyes.

“Get up, you bastard! I’ll not kill you while you’re lying on the floor!”

“Daniel!” Mercy grabbed his arm. “Don’t! Just make them go!”

Daniel looked down into her tear-filled eyes. His hand moved to her shoulder, gripped hard, then slid across her back and pulled her to him. Mercy leaned against him, and just for an instant he stroked the top of her shining head with his chin before he moved her away from him.

Daniel picked up Lenny’s hat and sailed it out the doorway and into the night. Then he fastened one hand in Lenny’s shirt, the other in his crotch, and threw him out after the hat as if he were no more than a bundle of straw.

Bernie was getting to his feet.

“I’m a-goin’,” he murmured as he staggered to the door, his hand on the back of his head where Mercy had hit him with the gun barrel. At the door he turned and reeled back toward the muskets propped against the wall.

“Leave them,” Daniel said sharply. “You can get them in the morning . . . at the mill. Then if I see you near Mercy again, you’ll wish I’d killed you tonight. Understand?”

Bernie staggered out the door and Daniel followed.

“Daniel! Don’t go!”

Daniel turned, and his eyes caught her pleading ones. The pain in her voice knifed into him.

“I’m not going.” His voice was deep and warm, confident, and . . . safe. It smoothed over her like a tender hand across a bruise.

“Mister?” Bernie’s voice came out of the darkness. “Air ya Sister’s man?”

“I’m the man who’s going to tear you up if you come near Miss Quill again.”

“We ain’t meanin’ ta do ’er no hurt. Our Maw’s been holdin’ off the dark angel o’ death so she could see little Hester once more. The Lord’s been callin’ her to come, but Maw’s been shuttin’ ’em out. Says she ain’t goin’ till Sister comes home. We done swore to find ’er fer Maw.”

“Mercy’s not your Sister,” Daniel grated out harshly. “Even if she was, you’re strangers to her. She’s lived here all her life with a family who loved her . . . looked after her.”

“She’s Hester,” Bernie said stubbornly. “I can’t be helpin’ it if’n she don’t claim kin ta us. She’s Hester Baxter. The Lord knows she’s Hester too.”

Standing just inside the door, Mercy closed her eyes and put her hands over her ears to keep from hearing any more of what was being said. Now a new fear invaded her, and a slow freeze of new horror and humiliation settled over her. She forced herself to breathe evenly, to marshal her thoughts. After all the years of wondering who she really was, did she know at last? Did the same blood run in her veins that ran in the veins of those two disgusting creatures? Oh, God! she cried silently. Please don’t let it be so.

Mercy opened her eyes to see Daniel close the door and drop the bar across it. When he turned, she lifted eyes filled with anguish to his face. He had always been there when she needed him, just as he was tonight. Mercy’s earliest memories were of Daniel, a boy with serious brown eyes and thick brown hair, holding her hand, taking care of her.

“Look at the tadpoles, Mercy, but keep out of the water.

“Put that down! You’ll cut yourself.

“Get out of that pen, you silly girl, before you’re stepped on.

“No, you can’t see the bull put to the cow! It’s not a sight for girls.”

Mercy realized that she had not looked at Daniel, really looked at him, for a long time. Now he was a man with a quiet clean-shaven face, deep-set mahogany-brown eyes, thick chestnut hair that curled over his ears and drooped down on his broad forehead. He had a large frame, but life had given him a lean trimness. Constant hard work had built a powerful body with a vast supply of vitality. He was self-assured and confident, a man who knew who and what he was, and who was comfortable with himself.

He was all that was dear and familiar in Mercy’s world, and now that world had suddenly been split apart. Her eyes fastened on his face in mute appeal.

“Oh, Daniel!” Her voice choked on the cry, and her face crumbled helplessly. Great tearing sobs shook her, and with a soft cry she ran to him and threw herself into his arms, crying hysterically.

“Don’t cry. Don’t cry,” he said against the top of her head. He held her close against his chest, one hand at the nape of her neck, the other soothing her back, waiting for the storm of tears to spend itself. “Shhhh . . . don’t cry. You’ll make yourself sick.”

No sound was as comforting to Mercy’s ears as Daniel’s voice, deep and warm, with a strange, intimate tone he used when speaking only to her. It had always been so. She had not been close to him like this since they were children. He was like a rock, a fort; she felt safe and cherished. She needed the closeness and security that lay within his arms. Her crying eased a little, though she still trembled under his caressing hands.

“Are you through now?” he asked as gently as if he were soothing a child. Firm fingers raised her chin, and a soft handkerchief wiped her eyes and nose. Slowly her lashes fanned up, and her enormous blue eyes, all shiny with tears, looked up into Daniel’s. “Where’s that sassy spirit you’ve had all these years?” he asked her. “Didn’t you tell Mamma you could stay here by yourself for a few nights? Didn’t you say that you didn’t need me to stay with you because it would give old Granny Halpen talk to spread up and down the river?”

“Yes, I said . . . that.” She gulped back the tears. “Please stay, Daniel. I don’t care about old Granny Halpen. Let her talk.” She leaned back and grasped his arm so she could look into his face. Her mouth trembled. “Do . . . you think I’m their Sister? I’ve always thought of myself as your Sister, yours and Zack’s and Mary Elizabeth’s.” A teardrop rolled down her smooth cheek and settled into the corner of her mouth. Her fingers clutched Daniel’s forearms as if she were about to slide off a cliff. “I don’t think I can stand it if I’m who they think I am.”

His arms tightened, and she clung to him as if only within his arms there was safety.

“Of course, you can stand it.” His voice was husky with emotion. “It wouldn’t make any difference to us here. You would still be Mercy Quill, daughter of Liberty and Farr Quill.” He nuzzled his face into the cloud of golden hair beneath his chin.

“But my blood would be the same as . . . theirs! Oh, Daniel, they had lice in their hair, they were filthy dirty, and they smelled like . . . like they’d been sleeping in a hog pen!” She looked up at him again, her eyes filled with the misery that was tearing her apart.

“We’re what our upbringing makes us,” Daniel said earnestly. “Maybe if they’d had the examples of Farrway and Liberty Quill to follow, they would be like you and me.”

“And if Papa hadn’t found me, I’d be like them. Is that it?” she demanded tearfully.

“You wouldn’t have minded, because you wouldn’t have known anything different.”

“But I do now! I’ll not go with them. I don’t know the woman who’s . . . dying. I feel sorry for her, but I don?

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...