- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

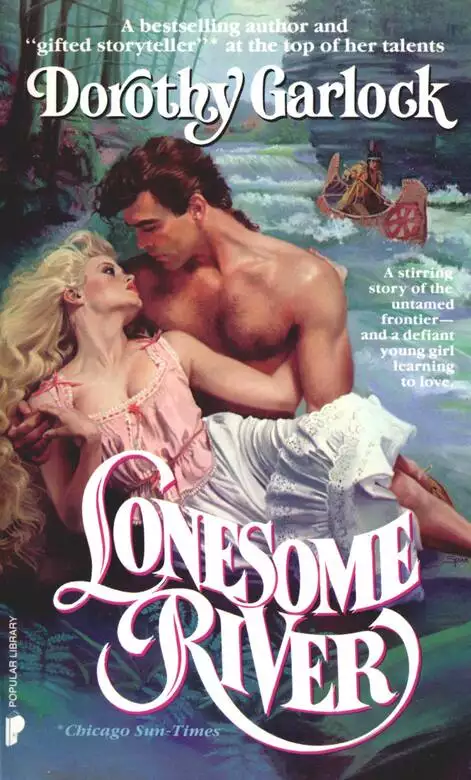

From top ranking historical romance writer, Dorothy Garlock, comes the first novel in a new trilogy. This is the romantic saga of a courageous widow who forges the Illinois frontier to make a new life. The author is an expert on the pioneer era, and she uses actual diaries and letters from that time to authenticate her stories.

Release date: April 12, 2001

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 389

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Lonesome River

Dorothy Garlock

“Hold me.

Kiss me, Farr—”

His lips trailed down the side of her face to her throat. His heart was pounding violently against her soft breasts. He hadn’t meant for this to happen tonight. She was tired and sore after her ordeal today; but when she turned to him and touched him, he hadn’t been able to help himself. Even as he was kissing her, a small voice in his head told him to stop . . . that he would hurt her.

“Liberty . . . I’ve got to know. I want you, but not unless you want me too. Do you . . . want me to leave you?” he whispered the words against her ear.

“Oh, please! Don’t leave me now!” Whatever comes, this night was hers. The thought that followed her words was so tangible in her mind that she didn’t know or care if she had voiced it. “Hold me, Farr. Hold me as if . . . you love me—just for tonight.”

His kisses came upon her mouth, warm, devouring, fierce with passion . . .

“Dorothy Garlock writes about love in such a way that one would almost believe she coined the word.”

—Affaire de Coeur

“You’ll find yourself actually there, right in the picture. You can feel the heat of the campfire, you can hear the wagon creaking and the slice and snap of the bullwhip. . . . There’s good reason why Dorothy has been called the ‘Louis L’Amour of the romance novelists.’”

—Beverly Hills California Courier

Books by Dorothy Garlock

Almost Eden

Annie Lash

Dream River

Forever Victoria

A Gentle Giving

Glorious Dawn

Homeplace

Lonesome River

Love and Cherish

Larkspur

Midnight Blue

Nightrose

Restless Wind

Ribbon in the Sky

River of Tomorrow

The Searching Hearts

Sins of Summer

Sweetwater

Tenderness

The Listening Sky

This Loving Land

Wayward Wind

Wild Sweet Wilderness

Wind of Promise

With Hope

Yesteryear

Published by

WARNER BOOKS

Dedicated to my son Herb and his wife Jacky, who give me luck and logic, laughter and love

“We are not turning back!” The girl’s gaze was as direct as a saber thrust, and her voice was as cold as its steel blade.

Elija Carroll looked at his daughter for a full minute before he spoke. “I jist said 1811 ain’t a good year fer movin’. The whole country’s in a hell of a mess. It’s agoin’ broke, is what it is. We ain’t ort a left Middlecrossin’ ’n come out here where there ain’t no towns, no folks, no nothin’. But if’n ya had to go, why clear to the Indiana? Ya could’ve stayed in the Ohio. Folks is pouring in thar. But ya jist want to roam around and see country, don’t ya? Why, there’s places at home that’s wilder’n all get out, if’n it was backwoods ya was seekin’.”

“Any year that you have to work is a bad year for you, Papa. You didn’t have to come along, but you did. You know why we came. Jubal and I couldn’t stay in Middlecrossing. Stith Lenning would have killed him. Jubal wanted to come, and I go where my husband goes. And you’ll go with me because you have no one but me and Amy, and you’re afraid you’ll die alone.”

“Yo’re hard, Libby. Hard. That school learnin’ yore ma give ya has dang near ruint ya. Ya ain’t never learned a woman’s place. Them fancy notions has made ya hard as any man I ever knowed.”

“You have to be hard to get through this life, Papa. You can call it hard and stubborn if you want to. If you’d had your way I’d be nothing but a drudge during the day and a whore at night. That’s what Stith Lenning wanted. He wanted me to cook his meals, keep his house, milk his cows, raise a house full of younguns to grow up to work his fields. He wanted me to do all that and fornicate all night long!”

“Hush yore mouth! It ain’t fittin’ fer a woman to be talkin’ such as that. A woman ort ta keep to her place—”

“What place is that? You expect me to work for my keep like a dumb milch cow, is that it? Work, service a man, and keep my mouth shut? I’ll be damned if I will! I’ll be his helpmate, but not his servant.” Liberty looked at her father’s bent, thin shoulders when he turned his back on her, as he always turned it against trouble. Her voice softened with resignation. “Oh, get some sleep. I’ll sit up with Jubal.”

Elija didn’t reply. There was plenty of argument left in him, but he knew he didn’t stand a chance to win. The only woman he had ever known who was like his daughter had been her mother, and during their entire married life he hadn’t won an argument with her. He had not been able to put an end to her independent ways, either, and the nonsense had been passed on to the daughter who was the spitting image of her.

For the past few days, Liberty had spent most of her waking hours tending her sick husband in the Dearborn wagon in which they were making the journey cross-country to Vincennes. Their two oxen and two horses were picketed nearby, and in the quiet she could hear the comforting sound of their stamping and cropping the grass. After leaving the boat at Louisville, they had joined four other families for the journey cross-country to the Wabash River. Now, because the settlers feared Jubal had the flux, Liberty’s family was forced to travel far behind the other wagons.

“Come on out and go to bed, Amy.” Liberty stood at the end of the wagon and helped her sister as she climbed over the tailgate. Twelve-year-old Amy was a slim, wiry girl with brown eyes and curly brown hair. She had been born to Elija’s second wife to whom he had been married a scant year when she died in childbirth.

“Jubal’s hot, Libby, awful hot. I kept the wet cloth on him like you said.”

“I’ll take over, now. Get under the wagon and get some sleep.” Amy crawled into the nest of blankets and Liberty dropped a sheet of canvas over her to shield her from the wind. She and Amy were forced to sleep under the wagon with Elija since their belongings and Liberty’s sick husband occupied all available space inside.

From inside the wagon Jubal Perry’s hacking cough became stronger, ending finally in a choked gurgle. Liberty climbed into the wagon and moved the copper dish containing the burning black gunpowder closer to the pallet of folded blankets. So far the acrid fumes had done little to clear the strangling phlegm from Jubal’s throat. His skin was stretched tightly over the bones of his face, and she could see the large veins throbbing at his temples. He had lost so much weight since they had started this journey that she doubted if his weight even equalled hers now.

Liberty didn’t know what else to do for him, and because of that, she felt a strong sense of guilt, a conviction that she was failing this man when he needed her most. He had stepped in and married her, giving her his protection and his name, and by doing so had snatched her from the clutches of Stith Lenning, who had been determined to have her.

A severe fit of coughing seized Jubal, and when it subsided he lay breathing heavily.

“You came out here more for me than for yourself, didn’t you, Jubal?” Liberty’s fingertips smoothed the sparse hair back from his dry, hot forehead. “You knew that if we stayed Stith would have found a way to have me even if he had to kill you. You gave up everything you had worked for to come to this new land. You’re such a gentle man, Jubal. All you ever wanted was to make your pots and jugs. But you insisted on coming—saying you wanted to go to your brother so I wouldn’t feel bad about you giving up so much. I guess in your own way, you’re as stubborn as I am.”

Jubal lay with his eyes closed. He had said very little all day. He had just lain there, not complaining as her father would have done. Liberty didn’t know if he had gone to sleep or not. Yet she talked, wanting him to know that she cared for him, in a way. He had not asked anything for himself, not even the consummation of the marriage. Jubal Perry was not the kind of man who fought for what he wanted. Small of stature and weak of body, he had made his pots, seemingly content to stand on the sidelines and watch life pass him by. The only daring thing he had ever done in his entire life was to marry Liberty Carroll, knowing a younger, stronger man wanted her desperately, and also knowing Stith was capable of killing to get her.

Stith Lenning, a storekeeper in Middlecrossing, had watched Liberty grow from a child, younger than her sister Amy was now, into a lovely young woman. He had planned for years to ask Elija for her hand in marriage. It wasn’t her comely features that attracted Stith so much as her strong, proud body, made for rutting and childbearing, and his desire to squelch her independent spirit. She also would have brought to the marriage her father’s hands to labor in the fields behind his store. In spite of Elija’s hangdog attitude and complaints of ill health, he had a good ten years of work left in him. Amy would have helped with chores in the barn and they would have brought oxen, horses, and a houseful of furniture Liberty’s grandfather, an excellent craftsman, had made. He would have beaten her when she was rebellious and scolded her for her foolish dreams. He would have made her old and worn out before she was thirty.

Jubal realized this. He married Liberty when she asked him, because her father wanted Liberty to marry Stith, and the law said a father had the right to give his daughter in marriage to a man of his choice. Stith was considered a rich man, and Elija saw years of easy living if his daughter married such a man. Jubal pampered her, provided for her father and sister, and when she wanted to leave Middlecrossing in upper New York State because she feared for his life, and because it would fulfill her dream of building a home in a new land, he sold his pottery shop and purchased supplies for the journey. During their year of marriage he had made no attempt to drive the laughter and ambition from her as Stith Lenning would have done. And now she felt a touch of shame, for she had only affection to give him, affection much like that a woman would give an older brother.

All through the long night hours Liberty applied warm cloths to Jubal’s chest, trying to relieve the congestion that was slowly strangling him. An hour before dawn she dozed, and when morning came, she looked out of the wagon and into a steady rain. The wagon was sitting on a small rise in the middle of a shallow pond.

“Libby! Come on out here. I ain’t likin’ what’s agoin’ on a’tall.” Elija stood at the end of the wagon with his shoulders hunched and spoke in a tired, fatalistic voice.

Liberty lifted her long skirts and climbed out over the tailgate. She could tell by the tone of her father’s voice and the way his head was sunk between his shoulders that he was unable to cope with whatever was wrong.

“What do you mean?”

“Jist that.” Elija waved his hand at the water standing in the trail and around the wagon. “The confounded rain is washin’ us away. Can’t nobody travel in sich weather as this here. We ain’t never agoin’ to get out of here. I said we ain’t ort a come,” he murmured in a tone that said he’d walked with trouble for a long time. “I told ya, and I told Jubal. We ain’t ort a come. But ya jist wouldn’t listen.”

Anger blazed into a sudden flame in Liberty’s mind, but she doused it with logical reasoning. There was nothing she could say that would change her father’s attitude. She gave him a quelling look, and he stopped talking.

“If the wagons up ahead can travel, so can we. We’ll hitch up and go on. Jubal needs medicine.” She bit her lower lip so she could speak without anger. “He needs medicine or he’ll die.” She said the words slowly as if her father didn’t understand.

“Where’ll ya find medicine? That a way?” He flung his hand toward the thick forest.

Fury reddened Liberty’s face and narrowed her eyes. She clenched her fists in frustration. “You don’t care if he dies! If he does you think we’ll turn back. We are not turning back. We’re going on until we reach the Wabash and follow it to Vincennes.”

“Oh, Lordy! Oh, Lordy, mercy me!” he wailed.

“Papa?” Amy crawled out of her nest under the wagon and went to him.

“I’m all right, sister. Get in the wagon outta the way.”

Amy ran to the back of the wagon and climbed in. Elija, moving slowly, sloshed through the water to where the oxen were tied and led them to the wagon.

Watching her father’s slow, ponderous movements, Liberty felt tears of rage run down her face, already wet with rain. There were times when she wished, truly wished, her father had remained in Middlecrossing. He was against every decision she made. Now there was the chance Jubal would die. The dampness and the jolting of the wagon might kill him, but what else could she do? They had to get to dryer ground before the water rose any higher.

As she worked, she thought of the words wheezed in her ear by Hull Dexter, the leader of the party that had moved on without them.

“Ya don’t hafta stay with ’em. Ya be a purty bit a fluff, even if’n ya are skinny as a starved rabbit. Ya ’n the gal can come with me. I’ll bed ya gentle like.”

“You buzzard bait!” she had replied. “I’d as soon bed down with a nest of rattlesnakes. Get your filthy hands off me.”

“Yore old man stinks like the flux. When he goes, bury ’em deep or the wolves’ll get ’em. If’n ya don’t come down with it, ya can c’mon ’n catch up. I’ll be waitin’ fer ya up ahead.”

“I’ll come on all right. I’ll get you, you rotgut, flea-bitten, son of a jackass! You took our money to lead us to Vincennes. You give it back or I’ll have the law on you. My brother-in-law is with the militia at Vincennes. He’ll—”

“Ya figgered he was at Limestone, then at Louisville.” Hull Dexter laughed. “If’n I warn’t sure yore old man’s got the catchin’ sickness, I’d not leave ya. Ya’d not be so feisty if’n ya had a real man atween yore legs ’stead a that puny thin’ ya got.”

“You’re not a man, Hull Dexter. You’re a . . . a lily-livered, bush-bottom warthog, is what you are.” She had shouted the words as he mounted his horse and told the others to move out. “Every blasted one of you put together wouldn’t make the man Jubal Perry is. You wait till Hammond Perry hears what you’ve done.” Liberty was so angry, unguarded words spewed from her mouth. “I’ll blacken your name all over this territory, you . . . louse! Hog! Rotten river trash! I’ll have you arrested and put in the stocks, and I’ll throw cow dung in your face! By jinks damn! I . . . I hope you all get scalped!”

Hull Dexter laughed heartily. “I’ll be back to get them fine horses, if’n the Injuns don’t steal ’em.”

The women from the other wagons were appalled by her outburst and turned their backs. Those riding climbed into the wagons, the ones walking switched the oxen, and the wagons moved away. Liberty had tried to make friends with them. They had tolerated her but made no overtures themselves. Deeply religious and subservient to their husbands’ wishes, they had been shocked to discover she was not properly submissive, that she argued with her father, spoke with the men as if she were their equal, left her hair uncovered at times, and was the one in charge of the family.

Liberty shook her fist at the departing wagons. Angry tears filled in her eyes.

“I’d prefer the Indians to have them rather than you, Hull Dexter. You’re a coward, a blackguard—”

“Hush up yore hollerin’, Liberty. Yo’re makin’ a plumb fool a yoreself. Ya ain’t gonna say nothin’ that’ll hurt ’em, ’n they ain’t carin’ what happens to us. Oh, Lordy! I don’t know what’s to become of us way out here in the wilderness all by ourselves.”

That was two days ago, and Elija’s voice of doom had droned continually since then.

“I jist knowed it’d turn out like this. I jist knowed we hadn’t ort a come. They ain’t even a track a them folks, we done dropped so fer behind. Ya jist wouldn’t listen, would ya? We had us a place, but ya had to go ’n get Jubal all riled up to leave it, atellin’ him tall tales ’bout Stith agoin’ to kill him. Ya just go a root-hoggin’ to get yore own way. Now see what ya’ve gone and done? Ya got me ’n Amy stuck off a way out here, ’n Jubal is dyin’—”

Liberty turned on him. “Hush up, Papa!” She lifted her skirts and pushed her way through the wet grass toward the horses. “Stop feeling sorry for yourself for a change! We had a place all right. It was Jubal’s place and right next to the Bloody Red Ox. That was right handy for you, wasn’t it, Papa? How long do you think we’d have stayed there? Another week? Month? Can’t you get it through your head that Stith was going to kill Jubal? He bragged about it to me and to Jubal. Jubal and I decided this together, Papa. I preferred to take my chances out here in the wilderness, and Jubal did too. He had rather come than stay there and face sure death.” Her last words were shouted angrily.

“Stith was a workin’ man. He warn’t agoin’ to kill nobody a’tall. I told ya when ya married Jubal that a dog what follows anybody what comes along ain’t worth a hoot. Beats me all hollow how two men can be so different. Stith had a good place, woulda give us a home. All Jubal done was fiddle around with them pots, atryin’ to make ’em pretty. But ya wouldn’t listen. Ya tied up with a man who pandered to yore foolish notions. I told Jubal a dozen times to look afore he jumped up ’n sold ever’thin’. He paid no more heed than ya did. To hear him tell it, ya knowed all that was fit to be knowed.”

Liberty took several deep gulps of air into her lungs, then said calmly but firmly, “Don’t ever say another bad thing about Jubal. If you do—I’ll take Amy and the wagon and leave you sitting right here. Do you understand, Papa?”

Elija snorted. “Back to that, are ya? Well, there ain’t no use arguin’ with a woman like ya are.” He shook his head. “Ya sure like shootin’ off yore mouth, but ya never listen to a word a body says. I might jist as well hush my mouth ’n save my breath.” He tied one of the horses behind the wagon and moved the oxen up in front and hitched them.

“Yes. Save it and use it to help me get this wagon someplace where we can build a fire, if not for Jubal’s sake, then for yours and Amy’s.” She picked up a stick and struck the patient ox on the rump. “Get to humping, Molly. Move on out, Sally.” The oxen strained at the yoke and slowly pulled the heavy wagon out of the mud and onto a trail that ran between trees so thick one could scarcely see twenty feet into their depth. “Amy,” Liberty called once they were moving, “how is Jubal?”

Amy came out of the wagon and climbed onto the seat. “He’s sleepin’, but he makes a awful racket.”

Liberty looked at her shivering sister. There was a scared, peaked look on her freckled face. Good heavens! She had forgotten how it upset Amy for her to argue with their father. Oh, God, she prayed. Please don’t let Amy get sick. Liberty’s greatest fear was that something would happen to Amy. Next was the fear that Stith Lenning would follow them into the wilderness.

“You’re all wet, love. Get back in there, put on something dry, and stay out of the rain. You don’t have to be afraid you’ll catch what Jubal has. Those ignorant louts that left us here wouldn’t know lung sickness from the pox.”

“Aren’t you hungry, Libby?”

“Sure, I am. We’ll be out of this bog soon. There’s a rise up ahead where I think we can stop. Papa should be able to find some dry wood for a fire under that thick stand of trees and I’ll fix us something hot. We’ll spend the day there. The wagons up ahead can’t make time in weather like this either.”

Liberty walked beside the oxen. Her long homespun dress was wet. It molded her shoulders and high pert breasts and clung to her slender thighs as she walked. She was not a tall girl, but her erectness and the proud way she carried her head made her seem tall. Her face was smooth and slightly tanned, a perfect oval frame for her straight, golden brown brows and large, clear, deep set eyes that were as blue as the feathers on a young bluejaw. Her slightly tilted nose and soft, red mouth were just there in her face, because it was her curly blond hair, a legacy from her Swedish mother, that drew one’s attention. She wore it parted in the middle, and now it hung to her hips in two long, soggy braids that were secured at the ends by a heavy linen string. In the rain the short hair about her face curled in ringlets so tight they resembled small corkscrews plastered to her forehead.

Back in Middlecrossing no one paid much attention to the color of her hair because there were so many blonds among the Dutch and Swedish families in the area. But the farther west they came, the more it was noticed, and in Louisville the rivermen had hooted and whistled when the string broke and her bonnet went sailing in the wind.

Liberty guided the oxen to a place where the branches of two huge oaks intermingled, making a canopy under which they could park the wagon. She could see where another wagon had parked in this place and where the traveler had left a circle of stones, made to enclose a cookfire.

She hoisted her skirts and climbed into the wagon as soon as she picketed the extra horse. Amy had changed her clothes and put on one of their father’s old buckskin shirts that hung below her knees. She climbed out onto the wagon seat and down the wheel to the ground.

“Jubal, are you awake?” Liberty knelt down and peered into his face.

“Libby?” he said weakly and groped for her hand. He held it to his feverish cheek. “I’m sorry I’m no help to you.”

“You will be when you’re feeling better. We’ll get a fire going and I’ll make you some hot switchel.”

“I don’t know, Libby. I don’t know if I can drink it.” His voice rasped and a severe fit of coughing seized him.

“Of course you can. I’ll put in a dab of rum.” She spoke gently when his coughing subsided. “You’ll get well, and we’ll build us a place near the river where you can get the finest clay to make your pots. People need jugs out here, too. Maybe we can send them downriver to New Orleans. I’ll do the farming and we’ll have milk and butter and eggs to make the nog you like so much.”

“I’m not much good to you, Libby.” His voice was so much like her father’s defeated voice that it frightened her.

“Yes, you are. You’re going to get well, or I’ll . . . or I’ll snatch you plumb bald, Jubal Perry. That’s what I’ll do,” she threatened with a catch in her voice, hoping he would smile.

He didn’t.

“We’re going to have that place we dreamed about, away from Stith Lenning, away from all of those pissants back in Middlecrossing who thought a jug was a jug as long as it held their corn liquor.” She brought his thin hand to her cheek, one of the few gestures of affection she had ever shown him.

“Is it still raining, Libby? I don’t know as I ever felt the cold and damp so much. I don’t know how Hammond has stood this country.”

“It’s only a puny little old drizzle now. Tomorrow the sun will be out and will dry things off. Try to sleep, Jubal. Are you warm enough?”

“I guess so. Are we keeping up? It seems like we go so slow and stop a lot.”

“We’re keeping up. We’re all stopping today because of the weather. It won’t be long, Jubal, and you’ll see Hammond.” Liberty felt not a twinge of guilt for the lie she was telling. She would tell a hundred lies, she vowed, if it would ease Jubal’s mind.

“I hope so. You’d better get out of those wet clothes or you’ll come down with the fever.” He wearily closed his eyes.

Liberty looked at him for a moment. His mouth was agape as he struggled to get air to his lungs. The daylight that filtered through the thick forest made the interior of the wagon dark and gloomy and gave a yellowish cast to his face. She could not remember feeling more helpless or more alone. It was her fault they were there. Jubal had given up everything to try to keep her out of Stith’s clutches. She knew it wasn’t fear for his life that prompted him to leave Middlecrossing. He had taken a fatalistic attitude about Stith killing him. Now he would die and be left in this lonely place.

She stroked his hot, dry brow and thought back to the day she had married Jubal. She had been sure Stith would back off and leave her alone, but that wasn’t the case. He seemed to be all the more determined. As the days, weeks and months passed, she was afraid to be alone even long enough to go to the outhouse. She talked it over with Jubal and they had decided to move West. Together they had reread the letters he had received over the last few years from his brother, Hammond, telling about the free land in the Illinois and Indiana country. He was a militiaman, and when Ohio became a state in 1803, he had been sent further west to posts along the Ohio River. At Limestone they were told he was at Louisville, and there they were told he was at Vincennes, so they had joined the party led by Hull Dexter, who promised to take them to the village on the Wabash River.

Liberty allowed herself one brief moment of regret for the pain she had caused her gentle husband, then she squared her shoulders and climbed out of the wagon. She unhitched the oxen and staked them beneath the tree where they could reach the long, green grass. Elija and Amy searched for dry wood. They found some and piled it beside the wagon. Liberty dug punk from a rotten log, poured on a small amount of black powder, then struck steel against flint to make a spark. It caught suddenly, and she fed in small twigs until it blazed brightly.

“How’s Jubal?” Elija asked without looking at her. It would take the rest of the day for him to end his pouting.

“His cough is worse.”

“He’ll choke is what he’ll do. Lung fever’s bad. Mighty bad. It dang near killed off the army at the Potomac. General Washington was in a fine kettle a fish, I tell you. Why, when I was a boy, my papa said—”

“Get some more wood, Papa. Then we’ve got to build some sort of shelter so I can cook something hot for Jubal and Amy.”

“Papa do this, Papa do that,” he grumbled. “Papa’s good enuff ta work, but he ain’t good enuff to listen to. And his advice ain’t worth a flitter.”

“Advice is like croton oil. It’s easy to give to someone else.” Liberty tried to take the sting from her words by smiling at her sister as she took a load of wood from her arms. “Are you warm now?”

“Uh huh. But I’m hungry.”

“I’ll make some pap and lace it with molasses. It’ll be good for Jubal too.”

“Won’t do no good. Won’t do no good a’tall.” Elija fed wood to the growing fire. “I told him it was foolhardy to come out here. I told him he ain’t the buildin’ kind a man. But it’s too late now.” He shook his head sadly. “Way too late.”

Liberty suspended the kettle over the fire, boiled the water, and sifted in finely ground cornmeal. While it bubbled, she filled the copper pot with water to make tea and the switchel for Jubal. She went to the wagon to feed him before she ate, but he was asleep and didn’t respond when she called his name.

They spent the rest of the morning looking for dry firewood, and most of the afternoon erecting a shelter. Elija complained about his back, and finally, with Liberty and Amy doing most of the work, the poles were set and a canvas that reached from the end of the wagon was stretched over them and tied down. The end of the canvas overhung the fire and helped throw the heat inside, dispelling the dampness inside the wagon.

“There’s gotta be a town here somewhere.” Elija had thrown himself down by the fire and hadn’t moved for an hour. “Them tracks is rutted. Wagons aplenty has been headin’ fer somewhere. Hull Dexter might not a been tryin’ to hornswaggle us, Libby. He could a knowed we be ’bout there.”

“Fiddle faddle! Of course those tracks are heading somewhere or else he wouldn’t be following them. And we’re not about there. Hull Dexter cheated us. He’s not scouting for us, hunting, protecting us from the savages. He left us to fend for ourselves because those ignorant louts thought Jubal had the flux. He refused to give any of our money back. He’s a rotten skunk, not fit for crow bait!”

Liberty was bone-tired, her mind not on what she was saying. Her gaze fixed abstractedly on the dim trail that disappeared into the thick forest. She was feeling lower and more frightened than she had in all her life. They were in a dense forest with a coach pistol and a rifle to defend themselves. And Jubal was dying. He hadn’t wanted to eat. He had swallowed barely a spoonful of food. When she tried to force it into his mouth he had choked. Late in the afternoon he had become delirious and had messed on the bedclothes. She had changed them, taken the soiled covers back down to the rain pond and washed them. Now darkness was drawing near, and she stood shivering, not wanting to listen to her father’s dire predictions.

“Bake your back for a while, Papa,” she said crossly. “I’ve got to get out of these wet clothes.”

Elija grunted and turned his back to her. “Ya want that I whittle ya a whistle, Amy?”

“If you want to.” Amy looked up at her sister and grinned. “He thinks I’m still a baby.”

Liberty loosened Amy’s

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...