***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected proof***

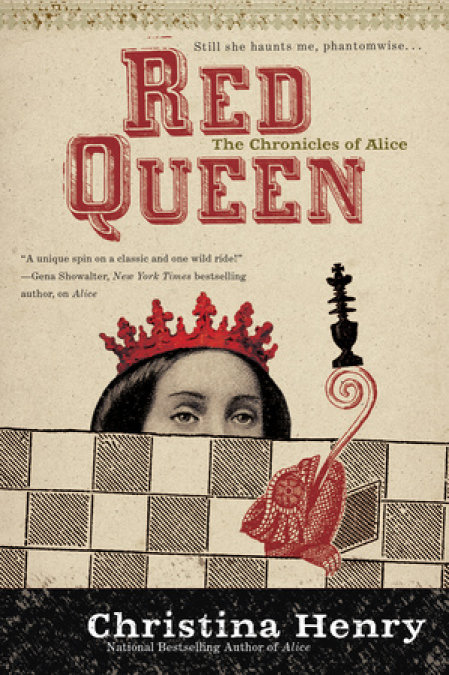

Copyright © 2016 Christina Henry

Red Queen excerpt

Prologue

An

Interlude

in the

Old City

In a City where everything was grey and fog-covered and monsters lurked behind every echoing footfall, there was a little man who collected stories. He sat in a parlor covered in roses and this little man was small and neat, his head covered in golden-brown ringlets and his eyes bright and green like a rose’s leaves. He wore a velvet suit of rose red and he urged a cup of tea on his visitor, a wide-eyed girl who looked about her in wonder. She was not certain how she’d gotten here, only that this strange little man had helped her when she thought she was lost.

“Do you like stories?” the little man asked.

He was called Cheshire, and the girl thought that was a very odd name, though this room and his cottage were very pretty.

“Yes,” she said. She was very young still, and did not know yet what Cheshire had saved her from when he came upon her wandering in the streets near his cottage. She was lucky, more than lucky, that it was he who found her.

“I like stories too,” Cheshire said. “I collect them. I like this story because I have a part to play in it—a small part, to be sure, but a part nonetheless.

“Once, there was a girl called Alice, and she lived in the New City, where everything is shining and beautiful and fair. But Alice was a curious girl with a curious talent. She was a Magician. Do you know what a Magician is?”

The girl shook her head. “But I have heard of them. They could do wonders but the ministers drove all the Magicians out of the City long ago.”

“Well,” Cheshire said, and winked. “They thought they did, but a few Magicians remained. And Alice was one of them, though she did not know it yet.

“She had magic, and because of that she was vulnerable, and a girl who was supposed to be Alice’s friend sold her for money to a very bad man called the Rabbit.”

“He was a rabbit?” the girl asked, confused.

“Not really, though he had rabbit ears on a man’s body,” Cheshire said. “The Rabbit hurt Alice, and wanted to hurt her more, wanted to sell her to a man called the Walrus who ate girls for their magic.”

The wide-eyed girl put her cup of tea on Cheshire’s rose-covered table and stared. “Ate? Like really eat?”

“Oh, yes, my dear,” Cheshire said. “He ate them all up in his belly. But Alice was quick and clever and she got away from the Rabbit before he could feed her to the Walrus. The Rabbit marked Alice, though, marked her with a long scar on her face to say she was his. My resourceful Alice marked him too—she took his eye out.

“But little Alice, she was broken and sad and confused, and her parents locked her away in a hospital for confused people. There she met a madman with an axe named Hatcher, a madman who grew to love her.

“Hatcher and Alice escaped from the hospital, and traveled through the Old City in search of their pasts and in search of a monster called the Jabberwocky who made the streets run with blood and corpses.”

The girl shuddered. “I know about him.”

“Then I should tell you that Alice, clever Alice, turned him into a butterfly with her magic so that he could never hurt anyone again, and she put that butterfly in a jar in her pocket and there he is till this day—unless he is dead, which is entirely possible.”

“And what of the Rabbit and the Walrus?” the girl asked. “What became of them?”

“Nothing good, my dear,” Cheshire said. “Nothing good at all, for they were bad men and bad men meet bad ends.”

“As they should,” the girl said firmly. “What about Alice? Did she have a happy ending?”

“I don’t know,” Cheshire said.

Part One

The

Forest

Alice was a Magician, albeit one who did not know very much about her own magic. She was escaping a City that hated and feared Magicians, which was one of the reasons why she didn’t know so very much about it. Alice was tall and blue-eyed and a little broken inside, but her companion didn’t mind because his insides were more jumbled than hers could ever be.

Hatcher was a murderer, and he knew quite a lot about it. Alice thought that Hatcher knew so much about it that he ought to be capitalized too—a Magician and her Murderer. He was tall and grey-eyed and mad and dangerous but he loved her too, and so they stayed together, both stumbling toward a future that would let them leave their past in the past.

She wished she could do something magical like in a fairy story—make a carpet to fly on, or summon up a handy unicorn to ride. It seemed very useless to be a Magician without spectacular tricks at hand.

At the very least she would have liked to be able to summon a bicycle, though the thought of Hatcher balancing on two wheels while holding his axe made her giggle. Anything would be better than this tunnel, an endless, narrow semidarkness with no relief in sight. She never would have entered it had she known it would take so long to get out again—three days at least, by her reckoning.

Alice thought it must be close to that long, although they had no true way to determine the passage of time.

They slept when they were tired, ate what little provisions they had left in the sack Hatcher carried. Soon enough they were hungry and thirsty, though it had become a familiar feeling and therefore just another discomfort. Food and water never seemed to be a regular occurrence since their escape from the hospital and its regular delivery of porridge morning and night.

During the long walk Alice dreamed of the open fields and trees that she would find at the end, a beautiful verdant land described by Pipkin, the rabbit they rescued from the Walrus’ fight ring. Anything, she thought, would be better than the crushing fog and darkness of the Old City.

Hatcher, in his own Hatcher way, alternated between moody silence and fits of mania. When not brooding he would run ahead of Alice and then back again over and over until he was white and breathless. Sometimes he stopped to box with the walls until his hands were bloody, or take chunks out of the wall with his axe. It seemed to Alice that there was more brooding and less running about than usual, though to be fair he had more to brood on.

He’d just remembered he had a daughter, more than ten years after she’d been sold to a trader far to the East. It wasn’t really his fault that he’d forgotten her, because the events of that day had turned him from Nicholas into the mad Hatcher he was now. Alice suspected that there was guilt and anger and helplessness all churned up inside him, and these feelings mixed with his dreams of blood and sometimes she saw all of this running over his face but he never spoke of it.

And, Alice thought, he’s probably a bit angry with me for putting him to sleep when it was time to face the Jabberwocky.

Alice didn’t regret the decision, though she knew it didn’t suit Hatcher’s notion of himself as her protector. Hatcher had a tendency to swing his axe first and think later, and as it happened, no blood-spilling had been required to defeat the ancient Magician.

She felt the reassuring weight of the little jar in her pants pocket, deliberately turned her mind away from it. Soon enough the Jabberwocky inside would be dead, if he were not already.

The tunnel, which proceeded along level ground since the initial entry into the Old City, sloped abruptly upward. It was then that Alice noticed the lanterns set at intervals had disappeared and that the interior of the cave was lightening.

Hatcher trotted up the steep incline while Alice labored after him, tripping several times and clawing in the dirt to push her body upright. Everything always seemed much harder for Alice, who was not as strong nor as graceful as Hatcher. Occasionally it seemed that her body was actively working against her progress.

When they finally emerged, blinking in the sunlight, Alice decided her disposition was not well suited to a life underground.

She crawled over the lip of the cave entrance, half blind after days underground and squinting through slitted eyes, expecting the soft brush of grass beneath her fingers. Instead there was something that felt like very fine ash, and a few scrubby grey plants poking brave faces toward the sun.

Alice forced her eyes to open wide. It took much more effort than it ought to; her eyes did not want all that glaring light and kept stubbornly closing against her will.

Hatcher ran ahead, already adjusted and seemingly glorying in the freedom after the constraint of the tunnel. She was aware of him as a half-formed shadow through her partially closed lids. He stopped suddenly, and his stillness made Alice struggle to her feet and take a proper look around. Once, she had she almost wished she hadn’t, for this wasn’t an improvement over their recent tunnel life.

They had emerged on the side of a hill that faced what must have once been an open meadow, perhaps dotted with wildflowers and trees and filled with tall grasses. Now there was nothing before them but a blackened waste stretching for miles, broken only by the occasional mound or hill.

“This isn’t what we expected,” Hatcher said.

“No,” Alice said, her voice faint. “What happened here?”

Hatcher shrugged. “There’s no one around to ask.”

Alice fought down the tears that threatened as she looked at the blight all around them. There was nothing to cry about here—no criminals kidnapping women, no streets lined with blood and corpses, no Rabbit to steal her away.

It’s only a wasteland. There’s no one here to hurt you or Hatcher. You can survive this. This is nothing.

Perhaps if she repeated this to herself often enough she could make it true. This is nothing, nothing at all.

But the promise of paradise beyond the walls of the City had sustained her, the dream of a mountain valley and the lake and a sky that was actually blue instead of grey. To have been through so much and discovered only this burned-out land seemed such a poor reward that crying seemed the only reasonable option. She let a few disappointed tears fall, saw them drop into the ash beneath her feet and immediately disappear. Then she scrubbed her face and told herself that was enough of that, thank you very kindly.

Alice walked around the hill to see what lay in the other direction. The New City sparkled in the distance, its high walls and tall white buildings shimmering on the horizon. Caught within the ring of the New City was the blackened sore of the Old City, completely encircled by its neighbor.

“I never realized it was so big,” Alice said as Hatcher joined her. His burst of energy had passed and he was subdued again, though by his troubles or by the landscape Alice did not know.

The combined Cities were a vast blot upon the landscape, stretching into the horizon. Of course it must be tremendous, Alice thought. It took them many days to cross from the hospital to the Rabbit’s lair, and still they had seen only a fraction of the Old City. The close-packed structures of the Old City had, somehow, made it seem smaller.

“Now what to do?” Alice muttered, returning to the cave entrance. Hatcher trailed behind her, silent, his mind obviously elsewhere.

They had counted upon being able to forage for food and water once they escaped the tunnel, but that seemed impossible now.

“There must be a village or town somewhere,” she said to Hatcher. “Not everyone in the world comes from the City. And there must be something beyond this blight, else Cheshire and the other Magicians would not have been interested in maintaining the tunnel.”

Hatcher crouched and ran his fingers through the dark substance that covered the ground. “It was all burned.”

“Yes,” Alice agreed. “But burned unnaturally, somehow. That doesn’t seem like ordinary fire ash.”

“Magic?” Hatcher asked.

“I suppose,” she said. “But why would a Magician want to burn all the land in sight? And how recently has all this occurred? It seems the burning goes right up to the edge of the New City. How was it that the City was not burned too?”

“Whatever happened, you can be certain that no one in the City was told of it,” Hatcher said.

“But the residents of the New City,” Alice said. “How could such a thing occur without their notice?”

“You once lived in the New City,” Hatcher said. “Did you notice anything that you weren’t told to notice by the ministers?”

“No,” Alice admitted. “But then, I was a child when I lived there. I didn’t notice much beyond my own garden, and my governess, and my family.”

And Dor, she thought, but she didn’t say it aloud. Little Dor-a-mouse, scuttling for the Rabbit. Dor, who had sold Alice to a man who’d raped her, who’d tried to break her. Dor, her best friend in all the world.

Thinking of Dor made Alice remember their tea party with the Rabbit and the Walrus, and the enormous plate of cakes, beautiful cakes with high crowns of brightly colored frosting. She’d give anything for a cake right now, although not one of the Rabbit’s cakes, which had been filled with powders to make her sick and compliant.

For a moment she wished for one of Cheshire’s magic parcels filled with food, but then remembered that such a thing would require a connection to Cheshire that she didn’t want.

She might be able to summon up food for them. Her only excuse for not doing such a thing before was that she wasn’t yet accustomed to the idea of being a Magician. Perhaps, when they were far from the City, she could search for another Magician, one who might teach her. They couldn’t all be terrible, couldn’t all be like the Caterpillar and the Rabbit and Cheshire and the Jabberwocky.

She must stop thinking of the Jabberwocky. The wish had said she would forget him, and he would die because of that. So she needed to forget, because she never again wanted to see the results of the Jabberwocky’s rage. The streets of the Old City lined with bodies and rivers of blood, those streets utterly silent, nothing living remaining except her and Hatcher.

Much like this, really, Alice thought. Just her and Hatcher and the burned land.

Sitting in the ruins of what was probably magical fire, remembering the horrors committed by those men in the Old City, the belief of the existence of a good Magician seemed naïve.

“Maybe power corrupts them,” Alice said.

It was a frightening thought, one that made her suddenly reluctant to try any magic at all. She’d spent years under the influence of drugs that made her think she was insane. She was only just learning who Alice was, what it was like to be her own self. She would rather use no magic at all than become someone unrecognizable.

“Power corrupts who?” Hatcher asked.

“Hm?”

“You said, ‘Maybe power corrupts them.’”

“The Magicians,” she said. “We’ve yet to meet a decent one.”

“Yes,” Hatcher agreed. “That doesn’t mean they don’t exist. In the story Cheshire told us, a good Magician saved the world from the Jabberwocky. At least for a while.”

“Of course,” Alice said. “I’d forgotten.”

“It’s easy to forget the good things,” Hatcher said, and this statement seemed to set off another fit of brooding. He sat back in the ash and began idly drawing with the point of one of the many knives he carried.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved