one

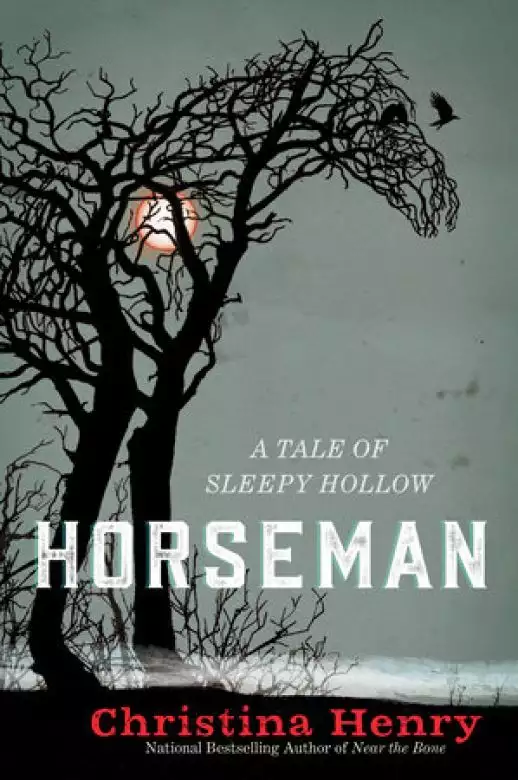

Of course I knew about the Horseman, no matter how much Katrina tried to keep it from me. If ever anyone brought up the subject within my hearing, Katrina would shush that person immediately, her eyes slanting in my direction as if to say, "Don't speak of it in front of the child."

I found out everything I wanted to know about the Horseman anyway, because children always hear and see more than adults think they do. Besides, the story of the Headless Horseman was a favorite in Sleepy Hollow, one that had been told and retold almost since the village was established. It was practically nothing to ask Sander to tell me about it. I already knew the part about the Horseman looking for a head because he didn't have one. Then Sander told me all about the schoolmaster who looked like a crane and how he tried to court Katrina and how one night the Horseman took the schoolmaster away, never to be seen again.

I always thought of my grandparents as Katrina and Brom though they were my grandmother and grandfather, because the legend of the Horseman and the crane and Katrina and Brom were part of the fabric of the Hollow, something woven into our hearts and minds. I never called them by their names, of course-Brom wouldn't have minded, but Katrina would have been very annoyed had I referred to her as anything except "Oma."

Whenever someone mentioned the Horseman, Brom would get a funny glint in his eye and sometimes chuckle to himself, and this made Katrina even more annoyed about the subject. I always had the feeling that Brom knew more about the Horseman than he was letting on. Later I discovered that, like so many things, this was both true and not true.

On the day that Cristoffel van den Berg was found in the woods without his head, Sander and I were playing Sleepy Hollow Boys by the creek. This was a game that we played often. It would have been better if there were a large group but no one ever wanted to play with us.

"All right, I'll be Brom Bones chasing the pig and you be Markus Baas and climb that tree when the pig gets close," I said, pointing to a maple with low branches that Sander could easily reach.

He was still shorter than me, a fact that never failed to irritate him. We were both fourteen and he thought that he should have started shooting up like some of the other boys in the Hollow.

"Why are you always Brom Bones?" Sander asked, scrunching up his face. "I'm always the one getting chased up a tree or having ale dumped on my head."

"He's my opa," I said. "Why shouldn't I play him?"

Sander kicked a rock off the bank and it tumbled into the stream, startling a small frog lurking just under the surface.

"It's boring if I never get to be the hero," Sander said.

I realized that he was always the one getting kicked around (because my opa could be a bit of a bully-I knew this even though I loved him more than anyone in the world-and our games were always about young Brom Bones and his gang). Since Sander was my only friend and I didn't want to lose him, I decided to let him have his way-at least just this once. However, it was important that I maintain the upper hand ("a Van Brunt never bows his head for anyone," as Brom always said), so I made a show of great reluctance.

"Well, I suppose," I said. "But it's a lot harder, you know. You have to run very fast and laugh at the same time and also pretend that you're chasing a pig and you have to make the pig noises properly. And you have to laugh like my opa-that great big laugh that he has. Can you really do all that?"

Sander's blue eyes lit up. "I can, I really can!"

"All right," I said, making a great show of not believing him. "I'll stand over here and you go a little ways in that direction and then come back, driving the pig."

Sander obediently trotted in the direction of the village and turned around, puffing himself up so that he appeared larger.

Sander ran toward me, laughing as loud as he could. It was all right but he didn't really sound like my opa. Nobody sounded like Brom, if truth be told. Brom's laugh was a rumble of thunder that rolled closer and closer until it broke over you.

"Don't forget to make the pig noises, too," I said.

"Stop worrying about what I'm doing," he said. "You're supposed to be Markus Baas walking along without a clue, carrying all the meat for dinner in a basket for Arabella Visser."

I turned my back on Sander and pretended to be carrying a basket, a simpering look on my face even though Sander couldn't see my expression. Men courting women always looked like sheep to me, their dignity drifting away as they bowed and scraped. Markus Baas looked like a sheep anyway, with his broad blank face and no chin to speak of. Whenever he saw Brom he'd frown and try to look fierce. Brom always laughed at him, though, because Brom laughed at everything, and the idea of Markus Baas being fierce was too silly to contemplate.

Sander began to snort, but since his voice wasn't too deep he didn't really sound like a pig-more like a small dog whining in the parlor.

I turned around, ready to tell Sander off and demonstrate proper pig-snorting noises. That's when I heard them.

Horses. Several of them, by the sound of it, and hurrying in our direction.

Sander obviously hadn't heard them yet, for he was still galloping toward me, waving his arms before him and making his bad pig noises.

"Stop!" I said, holding my hands up.

He halted, looking dejected. "I wasn't that bad, Ben."

"That's not it," I said, indicating he should come closer. "Listen."

"Horses," he said. "Moving fast."

"I wonder where they're going in such a hurry," I said. "Come on. Let's get down onto the bank so they won't see us from the trail."

"Why?" Sander asked.

"So that they don't see us, like I said."

"But why don't we want them to see us?"

"Because," I said, impatiently waving at Sander to follow my lead. "If they see us they might tell us off for being in the woods. You know most of the villagers think the woods are haunted."

"That's stupid," Sander said. "We're out here all the time and we've never found anything haunted."

"Exactly," I said, though that wasn't precisely true. I had heard something, once, and sometimes I felt someone watching us while we played. The watching someone never felt menacing, though.

"Though the Horseman lives in the forest, he doesn't live anywhere near here," Sander continued. "And of course there are witches and goblins, even though we've never seen them."

"Yes, yes," I said. "But not here, right? We're perfectly safe here. So just get down on the bank unless you want our game ruined by some spoiling adult telling us off."

I told Sander that we were hiding because we didn't want to get in trouble, but really I wanted to know where the riders were going in such a hurry. I'd never find out if they caught sight of us. Adults had an annoying tendency to tell children to stay out of their business.

We hunkered into the place where the bank sloped down

toward the stream. I had to keep my legs tucked up under me or else my shoes would end up in the water, and Katrina would twist my ear if I came home with wet socks.

The stream where we liked to play ran roughly along the same path as the main track through the woods. The track was mostly used by hunters, and even on horseback they never went past a certain point where the trees got very thick. Beyond that place was the home of the witches and the goblins and the Horseman, so no one dared go farther. I knew that wherever the riders were headed couldn't be much beyond a mile past where Sander and I peeked over the top of the bank.

A few moments after we slipped into place, the group of horses galloped past. There were about half a dozen men-among them, to my great surprise, Brom. Brom had so many duties around the farm that he generally left the daily business of the village to other men. Whatever was happening must be serious to take him away during harvest time.

Not one of them glanced left or right, so they didn't notice the tops of our heads. They didn't seem to notice anything. They all appeared grim, especially my opa, who never looked grim for anything.

"Let's go," I said, scrambling up over the top of the bank. I noticed then that there was mud all down the front of my jacket. Katrina would twist my ear for sure. "If we run we can catch up to them."

"What for?" Sander asked. Sander was a little heavier than me and he didn't like to run if he could help it.

"Didn't you see them?" I said. "Something's happened. That's not a hunting party."

"So?" Sander said, looking up at the sky. "It's nearly dinnertime. We should go back."

I could tell that now that his chance to play Brom Bones had been ruined, he was thinking about his midday meal and didn't give a fig for what might be happening in the woods. I, on the other hand, was deeply curious about what might set a party of men off in such a hurry. It wasn't as if exciting things happened in the Hollow every day. Most days the town was just as sleepy as its name. Despite this-or perhaps because of it-I was always curious about everything, and Katrina often reminded me that it wasn't a virtue.

"Let's just follow for a bit," I said. "If they go too far we can turn back."

Sander sighed. He really didn't want to go, but I was his only friend the same as he was mine.

"Fine," he said. "I'll go a short way with you. But I'm getting hungry, and if nothing interesting happens soon I'm going home."

"Very well," I said, knowing that he wouldn't go home until I did, and I didn't plan on turning around until I'd discovered what the party of horsemen was chasing.

We stayed close to the stream, keeping our ears pricked for the sounds of men or horses. Whatever the adults were about, they surely wouldn't want children nearby-it was always that way whenever anything interesting occurred-and so we'd have to keep our presence a secret.

"If you hear anyone approaching, just hide behind a tree," I said.

"I know," Sander said. He had mud all down the front of his jacket, too, and he hadn't noticed it yet. His mother would tell him off over it for hours. Her temper was the stuff of legends in the Hollow.

We had only walked for about fifteen minutes when we heard the horses. They were snorting and whinnying low, and their hooves clopped on the ground like they were pawing and trying to get away from their masters.

"The horses are upset," I whispered to Sander. We couldn't see anything yet. I wondered what had bothered the animals so much.

"Shh," Sander said. "They'll hear us."

"They won't hear us over that noise," I said.

"I thought you wanted to sneak up on them so they wouldn't send us away?" he said.

I pressed my lips together and didn't respond, which was what I always did when Sander was right about something.

The trees were huddled close together, chestnut and sugar maple and ash, their leaves just starting to curl at the edges and shift from their summer green to their autumn colors. The sky was covered in a patchwork of clouds shifting over the sun, casting strange shadows. Sander and I crept side by side, our shoulders touching, staying close to the tree trunks so we could hide behind them if we saw anyone ahead. Our steps were silent from long practice at sneaking about where we were not supposed to be.

I heard the murmur of men's voices before I saw them, followed immediately by a smell that was something like a butchered deer, only worse. I covered my mouth and nose with my hand, breathing in the scent of earth instead of whatever half-rotten thing the men had discovered. My palms were covered in drying mud from the riverbank.

The men were standing on the track in a half circle, their backs to us. Brom was taller than any of them, and even though he was the oldest, his shoulders were the broadest, too. He still wore his hair in a queue like he had when he was young, and the only way to tell he wasn't a young man were the streaks of gray in the black. I couldn't make out the other five men with their faces turned away from us-they all wore green or brown wool coats and breeches and high leather boots, the same style as twenty years before. There were miniatures and sketches of Katrina and Brom in the house from when they were younger, and while their faces had changed, their fashions had not. Many things never changed in the Hollow, and clothing was one of them.

"I want to see what they're looking at." I whispered close to Sander's ear and he batted at me like I was an annoying fly.

His nose was crumpled and he looked a little green. "I don't. It smells terrible."

"Fine," I said, annoyed. Sander was my only friend but sometimes he lacked a sense of adventure. "You stay here."

"Wait," he said in a low whisper as I crept ahead of him. "Don't go so close."

I turned back and flapped my hand at him, indicating he should stay. Then I pointed up at one of the maples nearby. It was a big one, with a broad base and long branches that protruded almost over the track. I hooked my legs around the trunk and shimmied up until I could grab a nearby branch, then quickly climbed until I could see the tops of the men's heads through the leaves. I still couldn't quite see what they were looking at, though, so I draped over one of the branches and scooted along until I had a better look.

As soon as I saw it, I wished I'd stayed on the ground with Sander.

Just beyond the circle of men was a boy-or rather, what was left of a boy. He lay on his side, like a rag doll that's been tossed in a corner by a careless child, one leg half-folded. A deep sadness welled up in me at the sight of him lying there, forgotten rubbish instead of a boy.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved