- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

ODD MAN OUT.

The Prequel to THE HUNTED!

Big for his age, young and impressionable drifter Charlie Chilton is taken in by the gruff leader of a gang of small-time crooks and ne'er do wells who sees something of himself in kindly, wayward Charlie. But Grady Haskell, ambitious ruffian with a shady past, soon joins the gang, convincing Charlie's friends to pursue a big score.

Charlie fails to thwart the crime and the heist turns bloody. As the only gang member caught alive, Big Charlie will soon swing for the crimes. He makes a daring escape, determined to track down Haskell and the gang and prove his innocence. Hot on Charlie's heels, a mysterious marshal and a posse of angry townsmen track him into the High Sierras, far to the north. Weaponless and with a vicious winter storm closing in, Big Charlie must find the killers and thieves before the seething posse turns vigilante and hangs him high.

Release date: June 2, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

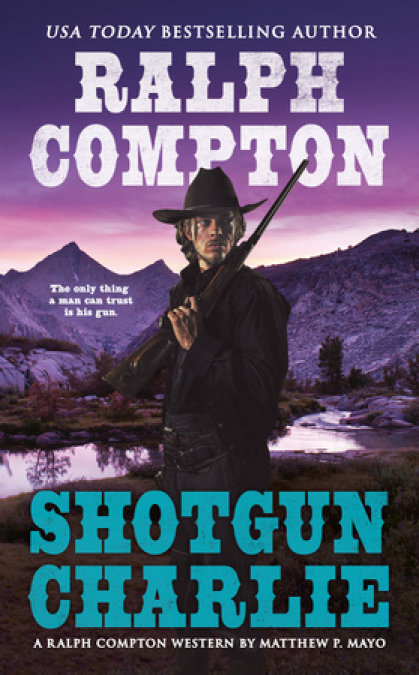

Ralph Compton Shotgun Charlie

Matthew P. Mayo

SHOTGUN CHARLIE

THE IMMORTAL COWBOY

This is respectfully dedicated to the “American Cowboy.” His was the saga sparked by the turmoil that followed the Civil War, and the passing of more than a century has by no means diminished the flame.

True, the old days and the old ways are but treasured memories, and the old trails have grown dim with the ravages of time, but the spirit of the cowboy lives on.

In my travels—to Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Arizona—I always find something that reminds me of the Old West. While I am walking these plains and mountains for the first time, there is this feeling that a part of me is eternal, that I have known these old trails before. I believe it is the undying spirit of the frontier calling me, through the mind’s eye, to step back into time. What is the appeal of the Old West of the American frontier?

It has been epitomized by some as the dark and bloody period in American history. Its heroes—Crockett, Bowie, Hickok, Earp—have been reviled and criticized. Yet the Old West lives on, larger than life.

It has become a symbol of freedom, when there was always another mountain to climb and another river to cross; when a dispute between two men was settled not with expensive lawyers, but with fists, knives, or guns. Barbaric? Maybe. But some things never change. When the cowboy rode into the pages of American history, he left behind a legacy that lives within the hearts of us all.

—Ralph Compton

Chapter 1

The dove’s throaty growls had startled him at first, made him jump right off the bed. Surely she was in pain, some sort of trouble. A bad dream at best. Then it had occurred to Charlie that no, this was a natural sound. And this was as close as he’d ever come to hearing it.

Through a thin lath-and-plaster wall mostly covered with paper—still pretty but not nearly so vivid as he was sure it had been a long time since, with tiny pink flowers, roses he thought they might be, surrounded by even tinier green leaves—Charlie finally knew the sounds for what they were. They were the sounds of a man and a woman doing what he was still a stranger to. Would be forever, he guessed.

And so big ol’ Charlie Chilton, barely fifteen years old, spent the first night he had ever spent in a town, the first night he’d ever spent in a hotel, the first night he’d ever spent in a bed—an honest-to-goodness spring bed under a cotton-ticking mattress and all—and he spent it mostly awake.

He wondered as he was roused again and again from a neck-snapping slumber, if he should rap on the wall. He didn’t want to invite trouble, but he needed sleep. He felt sure when he’d checked in that he was about to receive the finest night’s sleep a body could get.

That the hotel was in the habit of renting out unoccupied rooms for short-term trysts was something that Charlie would not know for a long time to come. But that night’s introduction had startled him. All the long days preceding his arrival to town had been one odd surprise after another, saddening and shocking and worrisome. And so this last one, despite his earnest hopes, proved more of the same.

This was what the world was like? Not much different from the everyday misery of life on the little rented farm with his gran. He’d hoped for so much more. As he listened to the moans and thumpings and occasional harsh barks of laughter from the men, he hoped that at least his mule, Teacup, was safe and sound and enjoying a good night’s slumber in the livery.

It had cost a few coins that he knew he shouldn’t have spent, but he’d never indulged in anything in his life and the money he’d earned at that last farm had burned a hole in his trouser pocket until he’d spent some.

Charlie passed some of the long, noisy night by counting out the last of it, searching his pockets over and over again, sure he’d dropped some of the money somewhere along the way. But no, when after long minutes he’d tallied the figures in his head, he had one dollar and twelve cents left. And he decided then that something had to change. He figured he’d worry about it in the morning, but morning came with little interruption from night by sleep, save for brief snatches.

He left the hotel early, when the sun was barely up. The woman’s cries had continued long into the early hours, then dwindled, allowing him precious little rest. Before he left the room, his eyes had once again taken in the small lace doily, a marvel of hand-stitching the likes of which he’d never seen. He’d studied it for some time the night before, then set it aside.

It was white, with a pointed-edge pattern, round, smaller than his palm, but large enough to fit under the dainty oil lamp on the chest of drawers. When he’d lifted the lamp to peek at it, he saw tiny flowers, a dozen of them arranged in a circle. It was one of the single most pretty things he’d ever seen in his life, if you didn’t count all the wonders nature had up her sleeve.

Those could hardly be topped by man, he figured—a new calf, the soft hairs on its head, how it felt when you rubbed it before the calf awoke, the long lashes on its eyes staring up at you in innocence, spring buds on an apple tree, then how they unfolded over a week or so, the little leaves getting bigger and darker and tougher as the season wore on.

They were special things, to be sure, but that little doily was a corker, maybe because it had no real purpose? Even its prettiness was hidden by the oil lamp. How many folks got to see what some woman had worked so hard to make, hidden as those little flowers were by the lamp? He appreciated them, at least.

And so as he left the room, he spied that doily and thought to himself, Why not, Charlie? Why not have something pretty in your life? After all, didn’t they sort of cheat you out of your good night’s sleep? And so he had slid it off the polished top of that chest of drawers and poked it quickly down into his trouser pocket with a long, callused finger, reddening about the neck, cheeks, and ears even as he did so.

By the time he reached the bottom of the long staircase in the lobby of the hotel, he felt as if his entire head might catch fire. He shuffled toward the front door and thrust a hand into his pocket. His fingers tweezered the crumpled little doily. He would set it on the counter and leave, walk right out. It was so early no one was there. He lifted it free and that was when he noticed the desk clerk, same man as the night before, in the mirror, was watching him from across the big room where he was busy sweeping the hearth of the great fireplace. How had Charlie not seen the thin, pasty-looking man when he came down the stairs?

Charlie nodded. The man watched him, didn’t look particularly angry. No angrier than he’d been the night before when Charlie checked in. He’d looked confused then and looked more of the same now. Charlie pushed the doily back down into his pocket and struggled with the fancy brass knobs of the lead glass doors, worry warring with fear and guilt in his brain. Worry and guilt that he’d stolen the first thing he’d ever stolen in his life, fear that he’d soon be arrested, and slim wonder too that maybe, just maybe, he’d get away with it.

By the time he reached the livery and, with frequent glances back over his shoulder, saw no one trailing him from the hotel, he became more and more convinced that he and he alone deserved to own that doily, that it was made and meant for him to admire, to appreciate. He rode out of that town and vowed, just the same, never to return to Bakersfield. Just in case.

Little did he know that a few short years later he would be a member of an outlaw gang dead set on committing a crime that made stealing a doily the very least of life’s offenses.

Chapter 2

Charlie Chilton woke in the dark and lay still, trying to remember where he was. Somewhere on the trail, somewhere out West. Far, far west of anywhere he’d ever been. There was a stream close by, and in the dark he heard its constant rush. It was an odd but welcome comfort.

It had been a week or more since he’d seen another person, which suited him fine. He’d been robbed and swindled and cheated so many times in the past few years since taking to the road that he didn’t have much left worth taking. Except for Teacup, the mule.

And that, his sleep-fogged mind told him, was exactly why he was in this forest, off the trail, and had been for a few days. Teacup was poorly and Charlie knew they wouldn’t be going on any farther together, so he’d made camp here. The best camp he could with what little he had. If he could see in the dark, he knew he’d see Teacup standing by the big pine, her legs locked, her bony old head leaned against the tree’s mammoth trunk. At least he hoped she was still standing.

Before he awoke, he had been smack-dab in the midst of the same dream he always had when he was in a bad way. Only thing was, the dream was a good one. Or at least something he could understand, not like some of those dreams like when he was flying or when mountains turned into the heads of sleeping giants or some other such craziness. This dream was a good one. Points of it were sad, to be sure, but it was the warm feeling of the dream that made him feel as he’d not felt in a handful of years of living out on the road by himself.

It always began the same way—he was standing over Gran’s grave, a fresh-packed affair that he himself had dug, then filled. It had been a lot like digging a posthole, only this time when he cracked open the bony ground he made the hole a long, narrow crater from side to side instead of top to bottom. In truth, the old woman wasn’t much more than a fence post herself. Certainly no bigger around, and she’d had the personality to match. Stubborn too.

He couldn’t pretend his upbringing by her had ever been easy, or particularly pleasant. She’d been a stringy old thing with a sour attitude and a resentment toward him that had nibbled away at him the entire fourteen years he’d been under her care—if it could be called that.

His father had been her son, the old woman he’d only ever known as Gran. He knew she had a proper given name; everyone had one. But so far as he could tell, there was little to no proof of it anywhere about the place.

Charlie had never gone into her private little bedroom in the three-room shack he’d lived in his entire life. The day she died, he entered that room for the first time in his life. In fact, he reckoned he should have gone on in earlier in the day, as she was still as a stick when he found her. He reckoned she’d died in the night.

He was surprised when he didn’t loose one tear on her behalf. He figured, despite the fact that she’d been a sour old thing all his days, that he would at least feel something about the passing on of this person, the only relative he’d ever known. But he hadn’t. Instead he felt that same creeping feeling of having lived through her slow-simmering, near-constant anger.

So why was it that whenever he recalled that burial scene in that blasted little dream that wouldn’t leave him alone, it always ended up the same way—him feeling some sort of happiness? No, happiness wasn’t quite the right word for it. More like a satisfied feeling. That somehow everything would work out all right.

It had been what, five, six years since that day when he buried the old woman? Then he’d loaded what few possessions he had on the old mule, Teacup, and headed on up that long dirt track to places unknown. He still recalled, with a knot in his throat and a twinge in his eye, the wide-open feeling that sort of washed over him, like a sudden summer shower on a hot-as-heck afternoon. The sort that feels good right when it happens, but you know you might pay for it quickly because such showers usually meant a choking-hot afternoon was soon to follow.

But right then, when he’d stopped at the end of the long lane that led to the little dirt farm where he’d spent his whole fourteen years, it was still raining, still fresh, still cool, still promising. The hot, sweltering feeling, the uncomfortable edge hadn’t set in yet. He knew he’d miss the place, but only because that was all he’d ever known.

He hadn’t even gone to a school. The one time he’d ever hinted at wanting to go, Gran had simply said no. “What you need schooling for when you already know all you need to take care of this here farm?” Then she’d given him that sour look that made him jelly inside. She’d turned back to complaining about how he was so big he should have been drowned at birth like an unwanted puppy instead of costing her all her life’s fortunes just to keep him in meals.

Charlie reckoned she had been a decent cook. There was never enough of it on the table to suit him, but what was there was always tasty.

And so he’d turned away from the little farm forever, a farm he learned hadn’t even belonged to her—she had merely been a tenant. He’d read that in what few papers he’d found in her things. He didn’t know what would become of the place, but he’d buried her beside his papa, her son and Charlie’s father. The man he’d been told by a few visitors over the years he greatly resembled in size and mannerisms. He had wished every day of his life that he’d been able to know the man. But his father had died when Charlie was but three.

Charlie had dim, vague memories of the man, a big, smiling face looking down at him, reaching to stroke his hair, the weight of a big hand on his head, the rough fingers of a workingman. The same hands he inherited, working the same fields behind the same mule that his father had been trudging along behind when he’d simply dropped in the field one day.

This much he knew because the old woman had blamed Charlie for her son’s death. He’d heard it said to him from her so often that he had never really questioned it, had assumed he’d somehow killed his father.

He felt a kinship with that old plodding mule. He’d taken to calling her Teacup because he liked the sound of the word. He’d heard it said in the little mercantile one day when he was a boy, on one of the few visits to town his gran had ever allowed him.

A woman in a fancy dress and a tall blue hat with purple feathers on it had said the word to the bald man behind the counter. He’d attended to her even though Gran had been in there first. Gran had sputtered all the way home about it in the wagon. She’d even turned to Charlie and said he was to blame.

The claim hadn’t shocked him. If he’d thought about it he would have guessed she would come around to arrive at that discovery sooner or later. In her eyes, everything in life was Charlie’s fault. Well, not everything. Only the bad things. He’d never in his life been responsible for anything good that had happened.

And so, all those years later, after leaving the little farm and its two sad graves, Charlie Chilton had roamed, not expecting much from himself, not knowing much more than the dulling, ceaseless ache of farm labor, plodding along beside Teacup until her own demise, quietly in the night, along a burbling valley brook a good many thousand miles, territories, and states to the west of where he’d grown up.

When light finally had come that morning, he somehow knew what he’d find before he rose, his thin blanket dropping to the hard earth on which he’d slept. Teacup was gone, laid out cold and quiet beneath the big tree. He reckoned when he awoke in the night that he should have gone to her, but what could a fellow like him do to stop the final claim that old age makes?

He wept long and openly over that mule’s passing more so than he did over his gran’s. He’d never ridden the mule in all those years he’d known her, never even thought of doing so. She was a companion, had always been so, not a critter to carry him.

He’d been doing a poor job at prospecting for gold, but he had acquired a pick, a shovel, and a pan. And with the pick and shovel he’d done his level best to bury the old, uncomplaining girl. It had taken him all day to make a dent in the hard root-knotted ground deep enough to roll her into—with much grunting and levering with a stout length of log.

When he was finished, he caught his breath, said a few words over her, then with as much dignity as he could offer old Teacup, covered her with dirt and topped that with rocks, a good many of them as big as or bigger than his head. Soon the jumble was a sizable cairn that he felt certain would keep critters from disrupting Teacup’s resting place.

Charlie felt a twinge of guilt over the big mounded pile, knew her body could feed plenty of critters looking for a toothsome treat, but he twinged even more inside when he thought of his old friend’s body savaged by wolves or bears or lions. He wasn’t even sure what territory or state he was in, not sure if any or all of those beasts lived there, but that didn’t matter. To him, they were all possibilities that didn’t sit well in his mind and left him feeling uneasy.

“Let them find their own food,” he wheezed as he rolled another boulder on top of the pile, for good measure.

By the time he was finished, he was exhausted, his hands were bloodied, and one of his thumbnails had been half pulled off when he jammed it too hard between two rocks, scrabbling to find purchase.

Cradling his wounded, throbbing hands in his lap, Charlie Chilton dozed off, dropping like one of those same stones deep into a pit of dark slumber, snoring like a bull grizz. When he finally awoke, it was to find himself wet through.

It was nearly dark and had apparently been raining for some time. It continued drizzling a solid, sluicing rhythm the rest of that day, on through the night, and for three days following. It soaked him and his meager belongings straight through. He was numb and cold and blue-lipped. It wasn’t until early the next morning that it occurred to him that something wasn’t right. He felt odd, sort of numb all over.

When the shivers began, trembling his substantial frame as if someone were shaking him from behind, he knew it was a sickness. He’d always been in good health, something he valued because his gran had frequently terrified him with sob-filled tales of how his father had died.

“Worked himself to death,” she’d howled. “And with no never mind paid to how his poor mother would fare in the world. I swear he wanted to kill himself. As soon as he come down with those chills and fevers, I knew he was a goner. I swear he done it to spite me. Then he stuck me with you!” She’d jam a little bony finger hard into his arm or chest or cheek and growl another few minutes. She’d tell him that as sure as she was a saint to put up with such cruelty, Charlie would end up like his father and leave her alone in the cold, cruel world.

And now here I am, he thought. Riddled with a sickness that like as not killed my daddy, and me without a soul around to help keep me alive.

It was this long, tight line of thinking that plagued Charlie enough that, despite the racking dry coughs that had begun to shake him alternately with the sudden shivers, he managed to gain his feet and try to kindle a fire.

But the relentless sheets of cold gray rain were more than he could battle. In the end, he managed little more than a cold, wet camp right beside the stone cairn he’d constructed for his dead friend. He stayed there for the better part of a week. Each day that passed felt worse than the one before.

After a number of days, he tried once more to stand, to make a fire, to get a drink, to do anything that felt normal. But none of anything felt normal anymore. All he ended up mustering out of himself were a few tired sighs, grunts, and wheezes. Finally he gave up and leaned back against the rock pile again.

“I expect I am to die right here and it probably won’t take all that long either.” He wasn’t sure if he spoke that or whispered it or imagined it. But that, along with a familiar image of what he always imagined his dead father had looked like, came to him then. It was a smiling face, much like his own, but more handsome, less thick-cheeked, and with a kindly glow.

But that was soon slapped down by the hovering, scowling face of his gran, waiting for what she’d predicted would always happen. He’d end up proving her right. That tag end of a thought burrowed into his mind and left him slipping into another layer of sickness, angry and saddened.

Chapter 3

“You see what I see, boys?”

Charlie heard the voice before he saw whoever it was it had come from.

“No? How can you say no, Simp? You got collard greens for brains? Oh, that’s right, I expect you do!”

The burst of jagged laughter that followed the odd remarks succeeded in pulling Charlie’s eyes open. He jerked back with a start and whapped his head on a rock. The pain of it, hot and throbbing, helped him focus his eyes as he reached up without thinking. The laughter that his painful action conjured swiveled his head and locked his eyes on what he hoped weren’t what passed for angels in heaven.

There before Charlie stood a group of four or five men, all on horseback, ringed before him. Back behind the men stood what looked to be a couple of pack animals, laden with crates and sacks, all lashed down with crisscrossed, well-used hemp rope.

Charlie’s first thought was surprise that he hadn’t heard all those men and horses coming along the path. As far as he could tell, the men, plus the pack animals, were for real and true. They looked alive enough. In fact, they looked like dozens of other hard men he’d seen over the years, always on the scout for trouble. Early in his days on the road, he’d seen a number of such men, men who treated him like an easy payday.

They’d robbed him of what little he had, or at least they had tried to. He’d always been much larger than others his age, so when Charlie grew angry, he had come to learn that others, even seemingly robust, frightening men, men whom he would consider fleeing from, all backed away from him. Fear glinted in their eyes, a look that told him they knew they had made a drastic mistake in picking on this lone traveler.

So when this haggard group of five men woke him, Charlie knew, by the way they were looking at him, that he was about to be robbed. The group of men broke, two walking their horses to one side of him, two to the other, one remaining in the center. Those to the sides slowly circled him, not taking much effort to hide the fact that they were working to get behind him.

He tried to muster up a big voice to bellow at them. He wanted to tell them they’d better look out because he was fast on his feet and twice as mean as a riled-up rattler.

He tried to let his shout rage at them, but all that came out was a big, hacking cough that doubled him over as he tried to stand, sending him flopping backward on the rock pile again.

When he came to, the same men were standing around him, and the older one who’d done the speaking earlier was bent over him. Other than the surprising kindness of the man’s eyes, it looked as if he was about to finish the job that Mother Nature hadn’t quite completed. The old man was missing half of his choppers so that he was gap-toothed. He sported a patchy, dull gray beard that might have had food stuck in it, and topping his lined, pocked face was a dented bowler hat, a bent silk flower, missing petals, drooping from the tatty band.

“Why, boy, you look plumb awful. You tangle with a she-lion or a boar grizz?”

“No . . . no, sir,” Charlie responded before he had time to think, and there it was, his tongue running across the forest floor.

“You hear that, boys? This big young’un here has already shown a heap more sense than the rest of you put together. He knows a sir when he meets one.”

The mumbles and rolled eyes from the other men told Charlie they paid the man’s comment little heed. Charlie refocused as the old man bent closer. It was then that he also noticed the big skinning knife wagging from the gent’s left hand.

Charlie tried to back away from him, succeeded only in worming up tighter to the rock pile. The effort tuckered him out and he sagged back again, working to breathe. There was a rank, unwashed sort of smell too that seemed to come from the old man. At least he only noticed it when the old man and the others had come around.

“Steady, boy. Steady. I ain’t gonna harm you. You’re all tangled in them clothes and blankets of your’n. Knotted tighter than a hatband on a banker’s head. You must have done some thrashing in your deliriums. I’m aiming only to cut them loose from you a bit so you can gain your legs. Though from the looks of you I’d say you’re a fair piece from standing.”

His face pulled away from Charlie and he heard him speak again. Charlie worked to pull in a breath. For some reason he was finding it hard as stone to draw a decent breath.

“Boys! Two of you get over here and lend a hand, drag this fella off of them rocks and lay him out over yonder, well away from this rock pile. Dutchy and Simp, you two mush-heads build a fire back a ways from where he had one. Too close to whatever it is he’s got hidden under them rocks.”

Charlie had trouble following what the old man was saying, but if he heard him right, someone wasn’t walking well and someone else was going to carry whoever it was. . . . He refocused on the old man. It startled him to see the face reappear, closer than before. Again, he was struck by the eyes set in such a craggy face. They seemed kindly. Something about them told Charlie here was a decent sort of fellow. Not at all what he’d looked at first to be.

“Boy, you hear me? Nod or say something if you can.”

Charlie fought for another breath. Then it occurred to him that the old man might be talking to him. Maybe he should say something, just the same. Just in case. He nodded, then said, “I . . . hear . . . you.”

The old man nodded again and smiled, his face inches from Charlie’s. “Don’t you worry. Ol’ Pap Morton’ll take care of you, see you right.”

“What for?” said a voice close by.

Without a pause in speaking, the old man narrowed his eyes and in a grim, tighter voice said, “You get that fire blazing yet, Dutchy? Course not, you’re an idiot. Numb as a . . .”

Charlie’s world pinched out with the sound of an old man’s reedy voice berating someone for something. For what, he didn’t know, didn’t care. All he knew was that he was probably dead or nearly so. Couldn’t even recall how he got to this sorry state . . . about to be robbed or worse by strange, hard, dangerous men bent on doing him harm. Probably leaving him for dead—ha, that’d be a laugh, a joke on them, as he was about there anyway.

Chapter 4

“What I’m trying to tell you, if you’d let me get a word in edgewise . . .” Grady Haskell poked the long barrel of his Colt straight into the fleshy tip of the man’s long nose. He pushed it, held it there for a moment, then pulled it away and looked close before smiling, then laughing. The barrel’s snout left a pucker, a dimple at the end of the long nose. But the man didn’t respond, didn’t jerk away because he was dead. His only reaction was a flopped head that revealed a ragged neck gash that welled blood anew. The wound was not an hour old.

“You, sir, are a plumb lousy conversationalist. Anybody ever tell you that?” Grady leaned in close again, as if waiting for a response. “Hmm?”

Getting no response, he howled again, upended a hazel-colored bottle, and bubbled back a few swallows. A thin stream of the burning rye whiskey dribbling out the corner of his stubbled mouth. “Time to get me a Chinese girl, a long, hot bath, and a cee-gar. Maybe even a steak and an Irish apple or two.” He belched and looked around him at the strange room. It should be strange to me, he thought. I have never before been here. And once I do what I need to here, I will take my leave and call it a day.

He fell asleep for a short time, awoke with a start, determined to kill whoever or whatever it was that had interrupted his earned slumber. He saw no one but the dead

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...