One

Ten years from now, when someone asks me how to survive life as a fat gay kid in a small West Texas town, I will tell them to become best friends with the school nurse. I learned from a very young age that the best way to brave the mean streets of Clover City was to endear myself to as many adults as humanly possible. Sure, being made fun of behind my back doesn’t exactly fill me with joy, but if being teacher’s pet saves me from merciless lunchroom politics, swirlies, black eyes, and boys chock-full of toxic masculinity, I’ll gladly do my time.

“Ms. Laverne!” I call with a fresh cafeteria churro in my fist. “It was shirts and skins day again,” I mutter just loudly enough for her to hear. “The shirts don’t fit and I resent that showing skin is my only other option.” I mean, honestly, if I’m going to show skin in gym class, it will be because I want to and have deemed the gym class worthy of my skin. Not because it’s my only option during our basketball unit. Frankly, the fact that I’ve lasted through all four years of high school without having to once don a shirt or strip to

skins is a testament to my resolve and inventiveness. That’s the kind of thing colleges should be looking for in prospective students.

The nurse’s office is empty as far as I can see, the curtain around the cot drawn shut. I creep closer, careful not to let my gym shoes squeak against the linoleum. Knowing Ms. Laverne, she’s taking a little afternoon siesta—and with only two months left in the school year, who could blame her?

I yank the curtain back and say, “Wakey, wakey!”

Ms. Laverne, who stands with her back to me, shrieks and twirls around, her gloved hands holding a jar of ointment and a wooden applicator.

The churro falls from my hands and hits the floor as I let out a gasp. Sitting right there on the cot without an ever-loving shirt on is Tucker Watson. He’s got the kind of farmer’s tan that I should find totally gross, leaving lines around his arms and neck so that his skin transitions from white to whiter. His medium-brown hair is freshly cut, and it’s the kind of hair that really needs an extra inch or two to adequately express itself. When he’s past due for a trip to the barber, you can see wild waves start to take shape. With eyes more gray than blue and full lips that only seem to smirk or slightly frown, he might seem a bit on the boyish side if it weren’t for his tall, muscular frame. Not that I’ve noticed.

“Um, wow. I am so sorry. I thought that—you wanna know what? I’m going to wait in the hallway.” And die. I’m going to go out into the hallway and die and then I’m going to tear open the floor with a jackhammer and dig my own grave. I’ll spend my afterlife haunting the halls of Clover City High and

warning all the other quietly gay boys that straight boys won’t love them back and that there is probably a whole great, wide world out there to discover full of perfectly suitable bachelors and dream careers. But I will never know, because I am dead. I am dead in the hallways of CCHS.

“Yes, Waylon,” says Ms. Laverne. “Why don’t you go ahead and wait out in the hallway for me? I’m nearly done with Tucker.”

Tucker smirks, because of course, and the way his two bottom teeth gap a little makes my guts rumble. To Tucker, I’m just Waylon, the same kid he’s gone to school with since we were hugging our respective moms’ legs as they dropped us off for our first day of kindergarten and the same guy he ditched mid–group project sophomore year. I try not to travel outside of my own very small social circle, and group projects are a perfect reminder of why I shouldn’t ever bother.

I wait out in the hall, and surprisingly, I do not die. A few minutes later, Ms. Laverne opens the door, and Tucker and I do an awkward tango as he tries to exit and I try to enter.

“Excuse me,” I grumble, my voice way deeper than it normally is.

“Sorry,” he grunts without bothering to make eye contact with me.

I don’t even try to respond before Ms. Laverne shuts the door, because if I open my mouth, I might hiss at him.

Ms. Laverne, a Black woman around the age of my grammy with soft brown walnut-shaped eyes and the most perfect Cupid’s bow I’ve ever seen, plops down on the cot. I take her chair, twirling in a circle,

like I’m some kind of office chair figure skater. (I can find the glamour in anything. My twin sister, Clementine, swears it’s a gift.)

Shaking her head, Ms. Laverne says, “You really did drop that piping-hot churro on my floor, didn’t you?”

I sigh. “And Gloria said it was their last one. Life is a series of tragedies.”

She lies back and crosses her ankles, her feet clad in bright white orthopedic shoes as they dangle off the edge. God, those things look comfortable. Why do all shoes that are basically pillows for your feet always have to be ugly? Is it some sort of sick universal law? Today Ms. Laverne’s hair is a wavy dark-brown bob with a few golden highlights. My first favorite thing about Ms. Laverne is her willingness to give me safe harbor. My second favorite thing about Ms. Laverne is her rotating collection of wigs.

“Shirts and skins in PE class, huh?” asks Ms. Laverne.

I nod.

“Life really is a series of tragedies,” she confirms.

Two

Clem and I are twins who have been raised with one universal truth: when you’re a twin, nothing is entirely your own. And for our sixteenth birthday, my parents demonstrated this by giving us every teenager’s dream gift: a car.

Of course, our parents would see no problem in giving us one single car. To share. The truck—or Beulah, as we have lovingly named her—is a cobalt-blue single-cab hand-me-down that was once Dad’s work truck. Since Clem barely passed the driving test—and in a rather traumatic fashion—she only drives when she absolutely has to. So I am her eternal designated driver. Still, this clunker of a vehicle is 50 percent hers, which is why I’m sitting in the parking lot waiting for my sister, who is waiting for her girlfriend.

Yeah, you heard that right. My twin sister is a lover of the ladies. Our parents basically hit the queer lottery.

“Clem!” I shout out the driver’s side window. “Clementine!”

She twirls around at the front of the parking lot, her mouth set into a deep pout. Two long orange

braids lie down the front of her shoulders over her striped ringer T-shirt, and bright red glasses frame her soft blue eyes. Mom always jokes that no one actually knows the real texture of Clem’s hair because she’s been wearing it in braids every day since we were kids. Straight out of the shower and into two braids. When I’ve prodded her about cutting them off, she gets weirdly defensive and begins to pet them, like they’re the source of everything that makes her Clementine. My twin is only a few inches shorter than me, which means she towers over her girlfriend, Hannah.

Just behind Clem, Hannah saunters out of the school entrance, flocked by her posse of oddball friends, and waves a quick goodbye to them. Even though Hannah’s general response to people seems to be that she’s allergic, she takes Clem’s hand, and her whole expression gets a massive glow up. Hannah is a small person with big energy. I can’t imagine she’s taller than five three, but honestly anything shorter than five nine and I lose my ability to discern height. You’re either shorter than me or much shorter than me. Unless you’re Tucker Watson, in which case you are slightly taller than me.

Hannah and Clem have been dating since last summer. They met only four days after Hannah’s then girlfriend, Courtney, broke up with her. Since Hannah is Clem’s first real girlfriend, I was scared she would be nothing more than a rebound for Hannah, but turns out I was wrong. Wouldn’t be the first time. If Clem dresses like she could be a kid on a playdate, Hannah looks more like an extra in Mad Max. They make an odd duo at times, but watching them together is like

watching two people who have gone their whole lives speaking a language only they can understand. Plus, Hannah isn’t as tough as she looks. Clem once confessed to me that she was named after a character from General Hospital, so I feel like having a daytime soap opera name means you have to have at least a slightly ooey-gooey center.

“Come on, come on, come on, come on,” I mutter to myself, tapping my thumb against the wheel. I timed today perfectly. If we run by and check on Grammy like Mom asked and make it home by four thirty, I should have just enough time to rewatch every episode of this season of Fiercest of Them All before tonight’s live finale. There are maybe three things I take seriously in this world, and Fiercest of Them Allis right up there after my grammy and my post–high school master plan.

Fiercest of Them All is in its sixteenth season and was basically Drag Queen 101 when I was a ten-year-old boy at the library pretending to do research on photosynthesis while I was actually watching YouTube clips of this mythical art of drag I never even knew existed. Honestly, I think some people in this town would have been less disturbed if they’d caught me looking at porn rather than grown men in dresses. Not that anyone should have been surprised. I’ve always been the kind of gay that announces itself and asks for a wide berth. Flamboyant, as Grammy says.

It was in that library that I gobbled up the history of drag and all the ways it’s woven into queer history, especially Black queer history, which is definitely not

something I had any luck finding reading materials on within a five-hundred-mile radius. Thank Goddess for the internet.

As for Fiercest of Them All, it wasn’t until I was in middle school that I figured out how to watch episodes from sort of sketchy websites. (I’d like to think that the drag gods would forgive me for my early and ill-informed pirating days.) Around that same time, all the things about me that signified to other people that I was definitely not straight grew bigger and took deeper roots.

Some people are obviously queer, and others . . . aren’t. I just so happen to fulfill some of the broader stereotypes surrounding gay guys. Mom once admitted that when I was younger, she and my dad thought it might be a phase. Maybe just my grandmother rubbing off on me. It’s true that her love for glamour, themes, and drama was contagious, but I never did grow out of it, so by the start of high school, watching Fiercest of Them All on the family TV was suddenly the least shocking thing about me. And sometimes, Mom and Dad even sat down to watch an episode, which in real time was annoying, because I was constantly having to explain context and how the show worked. Now, though, with only a few months left at home, it’s easy to feel nostalgic for their old-people quirks.

I honk—with love—as Clem pulls Hannah through the parking lot. My sister gives me a hmph as she slides in next to me with Hannah in the passenger seat.

“Sorry to make you wait, Waylon,” says Hannah in a voice that honestly doesn’t sound that sorry, if we’re splitting hairs. She bites on her lip ring, a recent addition and birthday gift from Clem. Not my style,

but it complements Hannah’s whole look, which is combat boots and shaggy bangs. Some people say the eyes are the windows to the soul, and if that’s the case, Hannah’s thick, wavy bangs are the curtains. Of course, there’s the matter of her teeth too. A little oversized and a little gapped. Hannah’s been getting shit about them for years, but what those losers don’t know is that some people become supermodels thanks to their quirky teeth, so if you ask me, Hannah’s teeth are a major future asset.

“He barely waited,” chimes in Clem. “We got out of school like eight minutes ago.”

“Listen,” I say as I shift the truck into drive. “It’s not my fault our parents have done us the inhumane disservice of not including DVR in their cable package.”

Clem groans. “It doesn’t even matter. This season is a done deal. Ruby Slippers has it in the bag.”

I let out a hiss as the truck rumbles out of the parking lot and into downtown Clover City. “Don’t you speak that evil in my Beulah.”

“Our Beulah. Our truck,” she reminds me.

“Mimi Mee is the one true queen of season sixteen and I will accept nothing less.”

“They’ll never crown a fat queen,” Clem says. “At least not anytime soon,” she adds gently.

Hannah lets out a here-we-go-again sigh.

“It’s not that I don’t think they should,” Clem continues. “But how many plus-size queens have we seen make it all the way to the finals season after season only to be shut down again and again? Honestly, I think we should stop watching altogether after this season. Go on strike.”

I roll my eyes. “Yeah, that’s going to make a real statement. Two kids from Clover City refusing to watch literally one of the biggest television shows in the world is going to make a real dent.”

Outside my window, Clover City ripples by in a blur as we make our way through downtown, past the weathered gazebos in the main square, and beyond the civic center. I’m not supposed to love this place. For as much as I love the fat queens on Fiercest of Them All, the small-town queens always hold a special place in my heart too. It’s a reminder that incredible things happen in all kinds of places, even Clover City. This is the kind of place gay teenage boys like me are supposed to dream of escaping. But my relationship with my hometown is much more complicated than that. Yeah, I think about the wider world out there and what it might have for me, but there’s also some comfort in walking into a room and feeling like the most refined, smartest person there. Even though Clover City feels like one big joke sometimes, it’s my joke. My charming joke of a town that thrives on beauty pageants and dance teams and a football team that couldn’t figure out how to win a game if the other team had forfeited, but underneath it all, it’s more than that small-town stereotype. It’s a shithole. But it’s my little shithole.

As we pull into Grammy’s driveway, Clem reaches over Hannah and opens the door before the truck is even in park.

Grammy lives in a house with her two best friends and fellow widows, Bernadette and Cleo. If it’s true what they say and that in our old age, we revert to our youth, Grammy’s in her party-girl college years. The

three of them are always driving out to New Mexico for the casinos and getting into trouble—sometimes even requiring bail. Basically, they’re everything I aspire to be.

I hope I live to be old and wrinkly with Clem, getting into as much trouble as humanly possible. Maybe I want to kill her more often than not lately, but the idea of riding into the sunset with her by my side is one hell of a way to go out if you ask me. (Assuming we both outlive our spouses, of course. Though I would be lying if I said I didn’t fantasize about being the town’s famous black widow, who wipes his tears away with piles of cash and furs. Just kidding. Murder is bad or something.)

Bernadette, an older Black woman with medium-brown skin who famously has a mole behind her ear in roughly the shape of Texas (seriously—she and it were in Texas Monthly), sits on the front porch in her rocking chair. “Darlinda! Your little chickadees are here and they brought that delightfully grumpy girl!”

“I’m not that grumpy,” murmurs Hannah as we get out of the truck.

I glance over the hood of the car at her. “Seriously?”

Clem catches her hand. “It’s endearing.”

“You’re grumpy,” Hannah retorts as she takes Clem’s hand. “Hi, Ms. Bernadette!” she calls in an extra-cheery voice.

“Really proving us all wrong,” I say.

The Hen House (as Grammy refers to it) is a basic brick ranch-style house, the kind that defines the nicer, older neighborhoods of Clover City. Except there’s nothing basic about this house. When Grammy, Cleo,

and Bernadette bought this place, they decided it would finally be the house of their dreams, unfettered by their husbands or the needs of their families. Much to their neighbors’ dismay, they painted the brick light pink and added yellow trim, as if the pink wouldn’t catch enough looks. If you think the outside of the house slows cars, you should see the inside.

Grammy, tall, white, busty, and broad, pushes the screen door open and beckons us inside. She stands framed by the doorway with her white hair tucked into a leopard-print bonnet, her hot-pink coveralls rolled up to her knees, and her shiny red toenails peeking out of her leopard-print kitten-heel slides. “Y’all come take a look at this faucet for me, would ya?”

Grammy dresses for every occasion of her life, whether she’s wearing an elaborate sundress to pick up her prescription, a teal faux-fur coat for bingo, or even a battery-powered cocktail dress on Christmas Eve with actual string lights. The woman loves a theme, so of course she would find her faucet is leaking and don her hot-pink coveralls before even putting in a call to her grandkids.

Inside, we each take our shoes off and leave them in the entryway. (The Hen House might be a bachelorette house, but these women are no slobs.)

Grammy takes turns hugging us all, including Hannah, whom she has a soft spot for. Takes a real fierce sort of person to pull off that much black. Chic, but edgy.

When Grammy hugs me, I hug her back, letting our embrace linger for a minute. Her perfume—the one she’s worn for as long as I can remember—is crisp and floral but not overpowering. Everyone ought to

have their own personal scent. Which is why I’ve been wearing two spritzes of Bleu de Chanel every day since she first bought it for me on my thirteenth birthday.

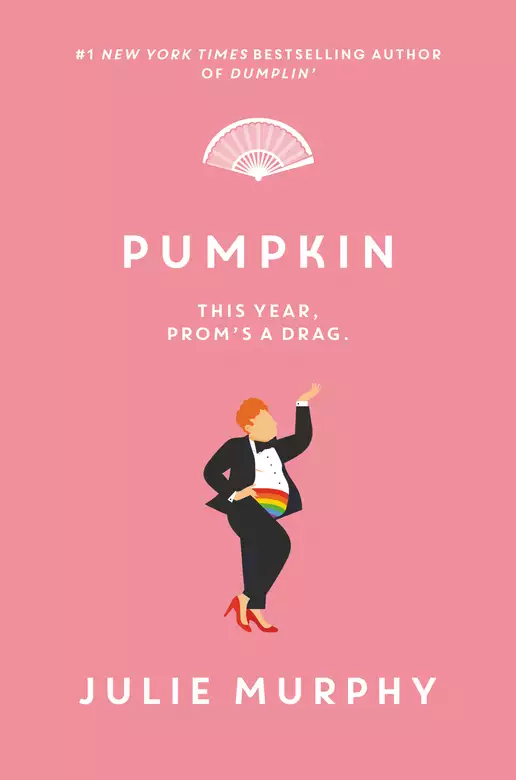

“Oooh, Pumpkin,” she says.

Pumpkin is more than a term of endearment. Orange hair and orange freckles set off by the pale white of our complexion. Grammy has called me Pumpkin since the day I was born. Clem’s a ginger too, of course, but with a name like Clementine, she didn’t need a nickname.

“We’ve got to make it fast today, Gram,” I tell her as I pull away. “We’re doing a marathon of Fiercest of Them All.”

Gram pinches my cheek. “You’ve got to teach me how to watch that on the streamer TV software y’all got me for Christmas. But first, let’s get this kitchen sink looked at. Come on, Hannah,” she says, taking Hannah’s hand. “You and I will have some rhubarb pie while these two have a look-see at my sink.”

Clem laughs. “She gets pie and I get to crawl under your sink. What kind of treatment is that for your only granddaughter?”

Gram snorts. “Perks of being family.”

Clementine gingerly takes the pink toolbox from the kitchen table and plops down on the ground, pulling me down with her. The toolbox was a Christmas gift from Dad. I remember him coughing into his fist as he said, “Now, I know a toolbox need not be pink for a woman to use it, but—”

“But it certainly is fabulous,” Gram finished.

Clem and I are well trained on basic household fixes. Dad owns a pavement striping company, but

he’s been known to pick up handy jobs, especially when we were younger and he was first starting out, so we spent a lot of summer days at Camp Dad while he jumped from job to job.

“Check the washer. It could be cracked,” I tell Clem, shining my cell phone light under the sink as I shimmy beneath the counter.

She grunts, wiping her hand on her jean shorts. “Nope, that’s not it.”

My brain wanders as Clem fidgets with the pipes and sink undercarriage. It’s not that I don’t know my way around a basic kitchen sink and it’s not like my sister is some kind of stereotype of a lesbian, but she’s got a brain for technical stuff. A mechanic’s brain is what Dad calls it.

Heck, she’ll probably be the smartest person at Austin Community College. We were both wait-listed at University of Texas, but convinced our parents to let us move to Austin to attend ACC until we’re accepted to UT.

Even if it’s only a few hours away, Austin is like a world away in terms of culture and has plenty of space for me to blossom into Waylon Stage Three. Waylon Stage One was Waylon before I came out of the closet. The entire history of me until that moment. Stage Two is my life in Clover City out of the closet, which hasn’t been unbearable, but is not exactly full of memories worth remembering. I try to dress in unassuming clothing and keep to myself at school, which sometimes works. Stage Three, though . . . that’s the big reveal. My butterfly moment. Austin will be the perfect arena. And Clem will be right there with me. The idea of us not going to the same school was

never on the table. It wasn’t even a discussion. Besides, Clem can barely drive. She wouldn’t get very far without me.

“Hand me that wrench, Waylon.”

I sit up too soon and hit my head on the frame of the cabinet. “Shit,” I whisper as I rub my forehead.

Grammy chuckles. “You’re lucky Cleo’s sunning herself in the backyard. She’d have a bar of soap between your teeth faster than you could say Judas.”

I retrieve the wrench and hand it off to Clem.

“Check the faucet, will ya?” she asks.

I hop up and peer out the window over the sink to the backyard, where Cleo is laid out on a lounge chair in an old-fashioned-looking black swimsuit with daisies lining the straps. She holds a big foil shield, like the kind you put in the window of your car, and is using it to reflect the sun onto her face.

“How does that white lady not have skin cancer?” asks Hannah.

Grammy takes a sip of her tea. “Cleo’s been oiling up with Crisco since we were girls and she’s already outlived two husbands and a boyfriend. She thinks she’s gonna live forever. There’s no telling her.”

I turn the faucet on. “No leak,” I confirm. Holding a hand out, I yank Clem up onto her feet. “That was fast.”

“Which means we’ve got time for pie,” says Clem as she plops down next to Hannah.

I let out a guttural groan and check the time on my phone.

Grammy takes my hand and pulls me down beside her. “Come on now, Pumpkin. Just a quick bite.” She

tugs on the collar of my polo. “I swear, with these clothes your mother buys, she’s got you lookin’ like a damn insurance adjuster.”

I roll my eyes and yank my hand free of hers. When I let loose, my mash-up of a southern Valley Girl voice and animated gestures might be a dead giveaway if your only barometer of a gay guy is how femme he is. But at school I do my best to keep a low profile, and that means steering clear of most social circles and wearing all the oversized polos and cargo shorts my mom showers me with on Christmas and birthdays. Handsome and sensible, as she puts it.

Clem’s mouth is already full of rhubarb and pie crust. “Oh, God, yeah. That’s the good stuff.”

“One slice,” I say.

Clem reaches for the pie server. “That was the appetizer slice. This is my real slice.”

“And then home,” I tell her.

She winks. “Sure thing, Pumpkin.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved