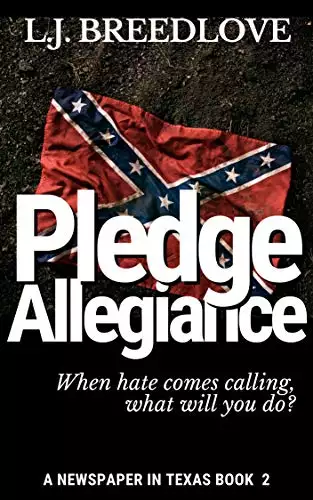

Pledge Allegiance

Dedication

This is the second book in A Newspaper in Texas, a historical mystery series set in the 1980s. It’s fiction, but it’s based on a true story of a young black man who refused to play football under the banner of the Confederate flag. I no longer remember his name, and I don’t know what became of him, but he has always been a hero of mine. It took guts to stand up for his beliefs in a state that takes football seriously, very seriously.

It would be easy to think that this is a thing of the past, that the Confederate flag is no longer an issue. But that’s not true. The Confederate flag continues to be a symbol of racism and division in our country.

Many people felt the election of a Black president demonstrated we were a “post-racist” society. But the hate that has surfaced since then shows we’re not. Just as hate surfaced against a young man who just wanted to play football.

This book is dedicated to that young man — and to the many young men who have stood up for what is right — and to the mothers who raised them right. Thank you.

Chapter 1

Saturday, September 7, 1987, 2 a.m.

The empty football stadium in Plains City, Texas, was eerie enough at night, and the body swinging from the goal posts wasn’t helping.

“Slow down, son,” Police Chief Jerry Don Hilliard said. “Don’t tear up the turf. They’ve got to play on it again tomorrow.”

“Yes, sir,” said the young officer who was driving. I was perched in the back seat, peering out between the two men. It had been a long day, full of ugly events. And the ugliest of them all waited for us down the field. If it hadn’t been for the earlier events, I wouldn’t have been in the police car at all. Cops don’t usually give reporters a ride to crime scenes. But I was at the police station — at 2 a.m. when the call came in — which tells you my day was bad, really bad. I grabbed my stuff and followed the Police Chief as he nearly ran toward the car waiting for him. When I got in the back seat, he just grunted.

The car slowed to a crawl, crossed the turf, and came to a stop at about the 50-yard line, where other police cars and an ambulance waited as if for some bizarre kind of kickoff. The chief flung open his door before the car was at a complete stop and went striding down the field. I followed, nearly running to keep up with him, my camera bag banging into my hip each step of the way.

The empty stadium blazed with light, but there was no sound except that of the emergency vehicles. The officers and EMTs stood looking at the end zone with almost none of the chatter I was used to. I’d been to a couple of games — there wasn’t much else to do in a Texas town on a fall Friday night — but it was different with people bustling toward seats, the band playing, and cheerleaders bouncing on the sidelines.

A breeze picked up some litter and blew it across the field in front of us. I looked around, spotting more litter and the signs of the people who’d left just hours before. Plains City High had its first game here tonight. They’d won, 21-20 — the score was still on the scoreboard.

The stadium was shaped like an oval bowl. To get into a game, people climbed up the equivalent of two flights of stairs to the eight gates at the top rim of the bowl. They then could walk down the inside into the bleachers. At the gate level, a large walkway went around the stadium’s circumference. Bleachers went up one more level above the walkway and down two levels below it. The concession stands and bathrooms were on the walkway, which created lines of impatient people to interfere with the traffic of people looking for seats. Now there were only uniformed cops along the walkway, searching the perimeter and watching. The cement, the lights, the officers.... It looked like a scene from Escape from New York.

The body was still hanging from the crossbar of the goal posts, swaying slightly in the white glare of the lights. Someone had lynched a Black man. I shook my head, hearing the haunting tunes of Strange Fruit sung by Billie Holliday. This was the 1980s. I thought lynching was a thing of the past.

Officers and paramedics stood below the hanging man, studying the situation. Officer Hank Fields approached the chief as we joined the throng.

“We’re not sure how they got him up there,” Hank said. He nodded at me.

“Backed a pickup underneath the goal posts, strung him up and drove off,” the chief said. We both looked at him, startled by his sureness, and he reddened. “It’s how you hang a dummy up there for a pre-game bonfire,” he explained, and then added gruffly, “So get the poor boy down, will you?”

It took a while — long enough for me to remember I was a reporter, well, editor actually, and pull out a camera and take some photos. I didn’t know whether we’d use pictures of the body, but I took them anyway. Shoot now, think later. Maybe after some sleep.

The officers found someone with a pickup, who pulled underneath. Then someone had to get up there and cut the rope. The officers studied the situation for a moment, and finally, two of them lifted the smallest guy up while he whacked at the rope. His hacking wasn’t particularly effective — you try swinging a knife while two guys hold you up in the air in the back of a pickup. Then the dead body came down all at once and two more officers eased it to the bed of the pickup, staggering under its weight.

I looked into the back of the pickup and forced myself to stare at the body. His face was congested, distorted. He’d bitten his tongue and blood drooled down his chin. Someone had beaten him before they strung him up. I turned away, sickened by the sight. I wasn’t alone. The officers were silent as they stood around waiting for orders.

The chief stood there staring at the dead young man for quite some time. “All right,” he said finally. “We’ve got a murder on our hands. I want the bastard who did this. You understand me? No screwups, no missing evidence, no flaws to this case. I want him. Nobody strings up young men in my town. You hear me?”

“I thought lynching was a thing of the past,” I ventured, repeating my earlier thoughts.

Jerry Don glared at me. “We won’t be using that term,” he said firmly. “And I’m asking you not to be using it in the newspaper either, Katy. We don’t need to feed the flames. That word brings fear to too many people. And fearful people can get very angry.”

“But chief,” I protested. “When you hang a Black man from the goal posts how is that not a lynching?”

“He was hung, Katy, that’s what we call it.”

Well I’d call it hanged, I thought, but fortunately didn’t say. Didn’t need to correct the Chief’s grammar. Besides if I started correcting Texans’ grammar, I’d never get it done.

Hilliard turned back toward the body. “And I’m going to have to go tell Miz Peabody that her only son is dead,” he muttered.

“Is that who you think it is?” I asked. “Is Clay missing?”

Officer Hank Fields shrugged. “We wanted to ask him some questions about what happened today. His mama didn’t know where he was, and she was worried. So, we decided we’d better take a look around.”

“See if he’s made it home yet,” the chief said, and Fields hurried toward a patrol car. I turned for one more look at the dead young man. Something stopped me, nagged at me. I studied the face again with a frown. “Chief,” I said slowly, and then louder. “Chief.”

“What?” he snapped. He was standing off to one side talking to one of his detectives.

“I don’t think that’s Clay Peabody.”

A couple of the officers, the detective and the chief clustered around me and looked at the body. “Katy, are you sure?” Jerry Don asked.

“No, I’m not sure,” I said, a bit snappish myself. “I only saw him at the rally earlier today and not up close.”

“Not to mention he’s been badly beaten since then,” Hank Fields muttered.

I grimaced. “Yeah. But Clay Peabody is a slender young man, as far as football players seem to go. Look at this guy’s shoulders.”

Everyone looked. The dead young man was built more like a tank. “If he didn’t play ball it was surely a waste,” someone muttered. “He’s big enough to be half the line.”

“If he’s not Peabody, who is he? And where is Peabody?” the chief growled, glaring at his men. “Well?” he barked. “Get Coach Owens down here and see if he can identify this boy. Donahue1 Fields! You still haven’t found Clay. Get looking.”

The paramedics lifted the body onto a stretcher. As they did, a piece a paper blew loose. I caught it. Smoothed it out.

“What’s that?” Hilliard snapped. I handed it to him.

“It says 1 down, 6 to go,” I said. It sounded vaguely like a football term, but its more macabre meaning frightened me. Earlier that day — well, yesterday now — six young football players led by the missing Clay Peabody had walked off the South Plains City High School football team to protest the Confederate flag the team carried at games. “Six players walked today,” I said. “So… who’s the seventh?”

Chief Hilliard looked at me and then said slowly, “I’d guess the seventh is your new reporter. You know where he is?”

I turned to Hank Fields. “Get me to a phone,” I said urgently. “Now!”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved