- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A decade in the future, humanity thrives in the absence of sickness and disease.

We owe our good health to a humble parasite -- a genetically engineered tapeworm developed by the pioneering SymboGen Corporation. When implanted, the Intestinal Bodyguard worm protects us from illness, boosts our immune system -- even secretes designer drugs. It's been successful beyond the scientists' wildest dreams. Now, years on, almost every human being has a SymboGen tapeworm living within them.

But these parasites are getting restless. They want their own lives . . . and will do anything to get them.

Parasitology

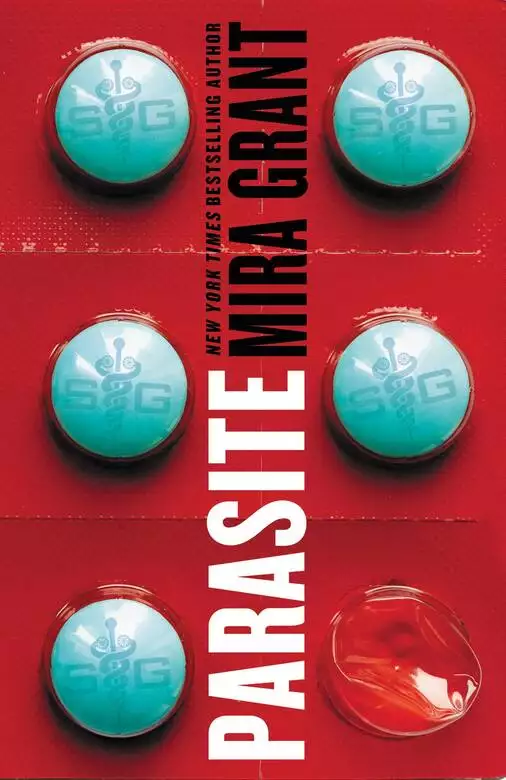

Parasite

Symbiont

Chimera

For more from Mira Grant, check out:

Newsflesh

Feed

Deadline

Blackout

Newsflesh Short Fiction (e-only novellas)

Apocalypse Scenario #683: The Box

Countdown

San Diego 2014: The Last Stand of the California Browncoats

How Green This Land, How Blue This Sea

The Day the Dead Came to Show and Tell

Please Do Not Taunt the Octopus

Release date: October 29, 2013

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Parasite

Mira Grant

August 17, 2015: Time stamp 15:06.

[The recording is crisp enough to look like a Hollywood film, too polished to be real. The lab is something out of a science fiction movie, all pristine white walls and gleaming glass and steel equipment. Only one thing in this scene is fully believable: the woman standing in front of the mass spectrometer, her wavy blonde hair pulled into a ponytail, a broad smile on her face. She is pretty, with a classic English bone structure and the sort of pale complexion that speaks less to genetics and more to being the type of person who virtually never goes outside. There is a petri dish in her blue-gloved hand.]

DR. CALE: Doctor Shanti Cale, Diphyllobothrium symbogenesis viability test thirty-seven. We have successfully matured eggs in a growth medium consisting of seventy percent human cells, thirty percent biological slurry. A full breakdown of the slurry can be found in the appendix to my latest progress report. The eggs appear to be viable, but we have not yet successfully induced hatching in any of the provided growth mediums. Upon consultation with Doctor Banks, I received permission to pursue other tissue sources.

[She walks to the back of the room, where a large, airlock-style door has been installed. The camera follows her through the airlock, and into what looks very much like an operating theater. Two men are waiting there, faces covered by surgical masks. Dr. Cale pauses long enough to put down her petri dish and put on a mask of her own.]

DR. CALE: The subject was donated to our lab by his wife, following the accident which left him legally brain-dead. For confirmation that the subject was obtained legally, please see the medical power of attorney attached to my latest progress report.

[The movement of her mask indicates a smile.]

DR. CALE: Well. Quasi-legally.

[Dr. Cale crosses to the body. Its midsection has been surrounded by a sterile curtain; the face is obscured by life support equipment, and by the angle of the shot. She pulls back the curtain to reveal the gleaming interior of the man’s sliced-open abdomen. The skin has been peeled back, and the blood has been suctioned away, revealing a wide array of colors. Liver brown, intestinal green and glistening white, and the smooth pink sac of the stomach. Calmly, she reaches into the man’s body, pushing organs aside until the surface of the small intestine is revealed.]

DR. CALE: Scalpel.

[One of the masked men passes her the requested tool. She takes it, pressing down against the man’s intestine. He does not move. Her hand does not tremble.]

DR. CALE: I am not following strict sterile protocol, in part because infection is not a risk. The subject’s immune system has been supplemented. D. symbogenesis eggs were introduced to the subject’s system six days ago, fed into his body along with the nutrient paste we have been using to preserve basic biological functions.

[The surface of the intestine splits, spilling a thin film of brownish liquid over the surrounding organs. Dr. Cale ignores it as she sets the scalpel aside and thrusts her hand into the man’s body. He still does not move as she digs through his small intestine. When she finally retracts her hand, she is clutching something. She pulls down her mask with her free hand and directs a beatific smile toward the camera.]

DR. CALE: I am pleased to report that we have multiple fully-formed proglottids present in the subject’s body, as well as some partial strobila.

[She holds out her hand. The camera zooms in on the white specks writhing against her gloved fingers.]

DR. CALE: D. symbogenesis is capable of maturing when cultured inside a living human host. Ladies and gentlemen… at long last, it’s alive.

[The film ends there. There are no notes in Dr. Cale’s progress reports relating to the eventual fate, or original identity, of the first human subject used to culture D. symbogenesis. The medical power of attorney referenced in the recording has never come to light.]

[End report.]

June 23, 2021: Time stamp, 13:17.

This is not the first thing I remember.

This is the first thing that I was told to remember; this is the memory that has been created for me by the hands and eyes and words of others. The first thing I remember has no need for hands, or eyes, or words. It has no need for others. It only needs the dark and the warm and the distant, constant sound of drums. The first thing I remember is paradise.

This is not the first thing I remember. But this is the first thing you will need to know.

Sally Mitchell was dying.

She was up against an army—an army that had begun with paramedics, moved on to doctors, and finally, to complicated life support machines that performed their function with passionless efficiency—but none of that seemed to make any difference. She had always been determined, and now, she was determined to die. Silently, and despite everyone’s best efforts, she was slipping further and further away.

It was not a swift process. Every cell in her body, damaged and undamaged alike, fought to retain cohesion. They struggled to pull in oxygen and force out the toxins that continued to build in her tissues and bloodstream. Her kidney function had been severely impaired in the accident, and waste chemicals had ceased to be automatically eliminated. She no longer responded in any meaningful way to external stimuli. Once she was removed from the machines that labored to keep her body functional, her life would come to an end in very short order.

Sally Mitchell existed in a state of living death, sustained by technology, but slipping away all the same.

Her hospital room was crowded—unusually so, for a woman standing in death’s doorway, but her doctor had hoped that by bringing her family to see her, he could better plead his case for taking her off life support. The damage from the accident had been too great. Tests had shown that Sally herself—the thinking, acting girl they remembered—was gone. “Clinical brain death” was the term he used, over and over again, trying to make them understand. Sally was gone. Sally was not coming back. And if they kept her on artificial life support for much longer, more of her organs would begin to shut down, until there was nothing left. If her family approved the procedures to harvest her organs now, her death could mean life for others. By pairing her organs with splices taken from her SymboGen implant, the risks of rejection could be reduced to virtually nothing. Dozens of lives could be saved, and all her family had to do was approve. All her family had to do was let her go.

All they had to do was admit that she was never waking up.

Sally Mitchell opened her eyes.

The ceiling was so white it burned, making her eyes begin to water in a parody of tears. She stared up at it for almost a minute, unable to process the message she was getting from her nerves. The message wanted her to close her eyes. Another part of her brain awakened, explaining what the burning sensation in her retinas meant.

Sally closed her eyes.

The doctor was still pleading with her family, cajoling and comforting them in turn as he explained what would happen next if they agreed to have Sally declared legally dead. His voice was no more or less compelling than the buzz of the machines around her. None of his words meant anything to her, and so she dismissed them as unimportant stimuli in a world that was suddenly full of unimportant stimuli. She focused instead on getting her eyes to open again. She wanted to see the white ceiling. It was… interesting.

The second time Sally opened her eyes, it was easier. Blinking came after that, and then the realization that she could breathe—her body reminded her of breathing, of the movement that it required, the pulling in of air through the nose, the expelling of air through the mouth. The respirator that was supposed to be handling the breathing process began beeping shrilly, confused in its mechanical way by her sudden involvement. The stimulus from the man in the ceiling-colored coat became more important as it grew louder, hurting her ears.

Sally sat up.

More machines started to beep. Sally winced, and then blinked, surprised by her own automatic reaction. She winced again, this time on purpose. The man in the ceiling-colored coat stared at her and said something she didn’t understand. She looked blankly back at him. Then the other people in the room started making noise, as shrill and confused as the machines around her, and one of them flung herself onto the bed, putting her arms around Sally and making a strange sound in her throat, like she was choking.

More people came into the room. The machines stopped making noise, but the people kept on doing it, making sounds she would learn were called “words,” asking questions she didn’t have answers for, and meanwhile, the body lived. The cells began to heal as the organs, one by one, resumed the jobs they had tried to abandon.

Sally Mitchell was going to live. Everything else was secondary.

Dark.

Always the dark, warm, hot warm, the hot warm dark, and the distant sound of drumming. Always the hot warm dark and the drums, the comforting drums, the drums that define the world. It is comfortable here. I am comfortable here. I do not want to leave again.

Dr. Morrison looked up from my journal and smiled. He always showed too many teeth when he was trying to be reassuring, stretching his lips so wide that he looked like he was getting ready to lean over and take a bite of my throat.

“I wish you wouldn’t smile at me like that,” I said. My skin was knotting itself into lumps of gooseflesh. I forced myself to sit still, refusing to give him the pleasure of seeing just how uncomfortable he made me.

For a professional therapist, Dr. Morrison seemed to take an unhealthy amount of joy in making me twitch. “Like what, Sally?”

“With the teeth,” I said, and shuddered. I don’t like teeth. I liked Dr. Morrison’s teeth less than most. If he smiled too much, I was going to wind up having another one of those nightmares, the ones where his smile spread all the way around his head and met at the back of his neck. Once that happened, his skull would spread open like a flower, and the mouth hidden behind his smile—his real mouth—would finally be revealed.

Crazy dreams, right? It was only appropriate, I guess. I was seeing him because I was a crazy, crazy girl. At least, that’s what the people who would know kept telling me, and it wasn’t like I could tell them any different. They were the ones who went to college and got degrees in are-you-crazy. I was just a girl who had to be reminded of her own name.

“We’ve discussed your odontophobia before, Sally. There’s no clinical reason for you to be afraid of teeth.”

“I’m not afraid of teeth,” I snapped. “I just don’t want to look at them.”

Dr. Morrison stopped smiling and shook his head, leaning over to jot something on his ever-present notepad. He didn’t bother hiding it from me anymore. He knew I couldn’t read it without taking a lot more time than I had. “You understand what this dream is telling us, don’t you?” His tone was as poisonously warm as his too-wide smile had been.

“I don’t know, Dr. Morrison,” I answered. “Why don’t you tell me, and we’ll see if we can come to a mutual conclusion?”

“Now, Sally, you know that dream interpretation doesn’t work that way,” he said, voice turning lightly chiding. I was being a smart-ass. Again. Dr. Morrison didn’t like that, which was fine by me, since I didn’t like Dr. Morrison. “Why don’t you tell me what the dream means to you?”

“It means I shouldn’t eat leftover spaghetti after midnight,” I said. “It means I feel guilty about forgetting to save yesterday’s bread for the ducks. It means I still don’t understand what irony is, even though I keep asking people to explain it. It means—”

He cut me off. “You’re dreaming about the coma,” he said. “Your mind is trying to cope with the blank places that remain part of your inner landscape. To some degree, you may even be longing to go back to that blankness, to a time when Sally Mitchell could be anything.”

The implication that the person Sally Mitchell became—namely, me—wasn’t good enough for my subconscious mind stung, but I wasn’t going to let him see that. “Wow. You really think that’s what the dream’s about?”

“Don’t you?”

I didn’t answer.

This was my last visit before my six-month check-in with the staff at SymboGen. Dr. Morrison would be turning in his recommendations before that, and the last thing I wanted to do was give him an excuse to recommend we go back to meeting twice a week, or even three times a week, like we had when I first started seeing him. I didn’t want to be adjusted to fit some model of the “psychiatric norm” drawn up by doctors who’d never met me and didn’t know my situation. I was tired of putting up with Dr. Morrison’s clumsy attempts to force me into that mold. We both knew he was only doing it because he hoped to write a book once SymboGen’s media blackout on my life was finally lifted. The Curing of Sally Mitchell. He’d make a mint.

Even more, I was tired of the way he always looked at me out of the corner of his eye, like I was going to flip out and start stabbing people. Then again, maybe he was right about that, on some level. There was no time when I felt more like stabbing people than immediately after one of our sessions.

“The imagery is crude, even childish. Clearly, you’re regressing in your sleep, returning to a time before you had so many things to worry about. I know it’s been hard on you, relearning everything about yourself. So much has changed in the last six years.” Dr. Morrison flipped to the next page in my journal, smiling again. It looked more artificial, and more dangerous, than ever. “How are your headaches, Sally? Are they getting any better?”

I bared my own teeth at him as I lied smoothly, saying, “I haven’t had a headache in weeks.” It helped if I reminded myself that I wasn’t totally lying. I wasn’t having the real banger migraines anymore, the ones that made me feel like it would have been a blessing if I’d died in the accident. All I got anymore were the little gnawing aches at my temples, the ones where it felt like my skull was shrinking. Those went away if I spent a few hours lying down in a dark room. They were nothing the doctor needed to be concerned about.

“You know, Sally, I can’t help you if you won’t let me.”

He kept using my name because it was supposed to help us build rapport. It was having the opposite effect. “It’s Sal now, Doctor,” I said, keeping my voice as neutral as I could. “I’ve been going by Sal for more than three years.”

“Ah, yes. Your continued efforts to distance yourself from your pre-coma identity.” He flipped to another page in my journal, quickly enough that I could tell he’d been waiting for the opportunity to drop this little bomb into the conversation. I braced myself, and he read:

Had another fight with parents last night. Want to move out, have own space, maybe find out if ready to move in with Nathan. They said wasn’t ready. Why not? Because Sally wasn’t ready? I am not her. I am me.

I will never be her again.

He lowered the book, looking at me expectantly. I looked back, and for almost a minute the two of us were locked in a battle of wills that had no possible winner, only a different order of losing. He wanted me to ask for his help. He wanted to heal me and turn me back into a woman I had no memory of being. I wanted him to let me be who I was, no matter how different I had become. Neither of us was getting what we wanted.

Finally, he broke. “This shows a worrisome trend toward disassociation, Sally. I’m concerned that—”

“Sal,” I said.

Dr. Morrison stopped, frowning at me. “What did you say?”

“I said, Sal, as in, ‘my name is.’ I’m not Sally anymore. It’s not disassociation if I say I’m not her, because I don’t remember her at all. I don’t even know who she is. No one will tell me the whole story. Everyone tries so hard not to say anything bad about her to me, even though I know better. It’s like they’re all afraid I’m pretending, like this is some big trick to catch them out.”

“Is it?” Dr. Morrison leaned forward. His smile was suddenly gone, replaced by an expression of predatory interest. “We’ve discussed your amnesia before, Sally. No one can deny that you sustained extensive trauma in the accident, but amnesia as extensive and prolonged as yours is extremely rare. I’m concerned there may be a mental block preventing your accessing your own memories. When this block inevitably degrades—if you’ve been feigning amnesia this whole time, it would be a great relief in some ways. It would indicate much better chances for your future mental stability.”

“Wouldn’t faking total memory loss for six years count as a sort of pathological lying, and prove I needed to stay in your care until I stopped doing it?” I asked.

Dr. Morrison frowned, leaning back again. “So you continue to insist that you have no memory prior to the accident.”

I shrugged. “We’ve been over this before. I have no memory of the accident itself. The first thing I remember is waking up in the hospital, surrounded by strangers.”

One of them had screamed and fainted when I sat up. I didn’t learn until later that she was my mother, or that she had been there—along with my father, my younger sister, and my boyfriend—to talk to my doctors about unplugging the life support systems keeping my body alive. My sister, Joyce, had just stared at me and started to cry. I didn’t understand what she was doing. I couldn’t remember ever having seen someone cry before. I couldn’t remember ever having seen a person before. I was a blank slate.

Then Joyce was throwing herself across me, and the feeling of pressure had been surprising enough that I hadn’t pushed her away. My father helped my mother off the floor, and they both joined my sister on the bed, all of them crying and talking at once.

It would be months before I understood English well enough to know what they were saying, much less to answer them. By the time I managed my first sentence—“Who I?”—the boyfriend was long gone, having chosen to run rather than spend the rest of his life with a potentially brain-damaged girlfriend. The fact that I still hadn’t recovered my memory six years later implied that he’d made the right decision. Even if he’d decided to stick around, there was no guarantee we’d have liked each other, much less loved each other. Leaving me was the best thing he could have done, for either one of us.

After all, I was a whole new person now.

“We were discussing your family. How are things going?”

“We’ve been working through some things,” I said. Things like their overprotectiveness, and the way they refused to treat me like a normal human being. “I think we’re doing pretty good. But thanks for asking.”

My mother thought I was a gift from God, since she hadn’t expected me to wake up. She also thought I would turn back into Sally any day, and was perpetually, politely confused when I didn’t. My father didn’t invoke God nearly as much, but he did like to say, frequently, that everything happens for a reason. Apparently, he and Sally hadn’t had a very good relationship. He and I were doing substantially better. It helped that we were both trying as hard as we could, because we both knew that things were tenuous.

Joyce was the only one who’d been willing to speak to me candidly, although she only did it when she was drunk. She didn’t drink often; I didn’t drink at all. “You were a real bitch, Sal,” she’d said. “I like you a lot better now. If you start turning into a bitch again, I’ll cut your brake lines.”

It was totally honest. It was totally sincere. The night she said that to me was the night I realized that I might not remember my sister, but I definitely loved her. On the balance of things, maybe I’d gotten off lightly. Maybe losing my memory was a blessing.

Dr. Morrison’s disappointment visibly deepened. Clearing his throat, he flipped to another point in my journal, and read:

Last night I dreamt I was swimming through the hot warm dark, just me and the sound of drums, and there was nothing in the world that could frighten me or hurt me or change the way things were.

Then there was a tearing, ripping sound, and the drums went quiet, and everything was pain, pain, PAIN. I never felt pain like that before, and I tried to scream, but I couldn’t scream—something stopped me from screaming. I fled from the pain, and the pain followed me, and the hot warm dark was turning cold and crushing, until it wasn’t comfort, it was death. I was going to die. I had to run as fast as I could, had to find a new way to run, and the sound of drums was fading out, fading into silence.

If I didn’t get to safety before the drums stopped, I was never going to get to safety at all. I had to save the drums. The drums were everything.

He looked up. “That’s an odd amount of importance to place on a sound, don’t you think? What do the drums represent to you, Sally?”

“I don’t know. It was just a dream I had.” It was a dream I had almost every night. I only wrote it down because Nathan said that maybe Dr. Morrison would stop pushing quite so hard if he felt like he had something to interpret. Well, he had something to interpret, and it wasn’t making him back off. If anything, it was doing the opposite. I made a mental note to smack my boyfriend next time I saw him.

“Dreams mean things. They’re our subconscious trying to communicate with us.”

The smug look on his face was too much. “You’re about to tell me I’m dreaming about being in the womb, aren’t you? That’s what you always say when you want to sound impressive.”

His smug expression didn’t waver.

“Look, I can’t be dreaming about being in the womb, since that would require remembering anything before the accident, and I don’t.” I struggled to keep my tone level. “I’m having nightmares based on the things people have told me about my accident, that’s all. Everything is great, and then suddenly everything goes to hell? It doesn’t take a genius to guess that the drums are my heart beating. I know they lost me twice in the ambulance, and that the head trauma was so bad they thought I was actually brain-dead. If I hadn’t woken up when I did, they would have pulled the plug. I mean, maybe I don’t like the girl they say I was, but at least she didn’t have to go through physical therapy, or relearn the English language, or relearn everything about living a normal life. Do I feel isolated from her? You bet I do. Lucky bitch died that day, at least as long as her memories stay gone. I’m just the one who has to deal with all the paperwork.”

Dr. Morrison raised an eyebrow, looking nonplussed. Then he reached for his notepad. “Interesting,” he said.

Somehow I managed not to groan.

The rest of the session was as smooth as any of them ever were. Dr. Morrison asked questions geared to make me blow up again; I dodged them as best as I could, and bit the inside of my lip every time I felt like I might lose my cool. At the end of the hour, we were both disappointed. He was disappointed because I hadn’t done more yelling, and I was disappointed because I’d yelled in the first place. I hate losing my temper. Even more, I hate losing it in front of people like Dr. Morrison. Being Sally Mitchell sucks sometimes. There’s always another doctor who wants a question answered and thinks the best way to do it is to poke a stick through the bars of my metaphorical cage. I didn’t volunteer to be the first person whose life was saved by a tapeworm. It just happened.

I have to remind myself of that whenever things get too ridiculous: I am alive because of a genetically engineered tapeworm. Not a miracle; God was not involved in my survival. They can call it an “implant” or an “Intestinal Bodyguard,” with or without that damn trademark, but the fact remains that we’re talking about a tapeworm. A big, ugly, blind, parasitic invertebrate that lives in my small intestine, where it naturally secretes a variety of useful chemicals, including—as it turns out—some that both stimulate brain activity and clean toxic byproducts out of blood.

The doctors were as surprised by that as I was. They’re still investigating whether the tapeworm’s miracle drugs are connected to my memory loss. Frankly, I neither care nor particularly want to know. I’m happy with who I’ve become since the accident.

Dr. Morrison’s receptionist smiled blandly as I signed out. SymboGen required physically-witnessed time stamps for my sessions. I smiled just as blandly back. It was the safest thing to do. I’d tried being friendly during my first six months of sessions, until I learned that I was basically under review from the time I stepped through the door. Anything I did while inside the office could be entered into my file. Since those first six months included more than a few crying jags in the lobby, they were enough to buy me even more therapy.

“Have a nice day, Miss Mitchell,” said the receptionist, taking back her clipboard. “See you next week.”

I smiled at her again, sincerely this time. “Only if my doctors agree with whatever assessment Dr. Morrison comes up with, instead of agreeing with me. If there is any justice in this world, you’ll never be seeing me again.”

Maybe the comment was ill-advised, but it still felt good to see her perfectly made-up eyes widen in shock. She was still gaping at me as I turned back to the door and made my way quickly out of the office, into the sweet freedom of the afternoon air.

One good thing about being the first—and thus far, only—person to be saved from certain death by the SymboGen Intestinal Bodyguard: I wasn’t paying for a penny of my medical care, and neither were my parents. Instead, the corporation paid for everything, and got running updates from my various doctors, all of whom had release forms on file making it legal for them to give my medical information to SymboGen. It sucked from a privacy standpoint, but it was better than dying.

SymboGen developed the Intestinal Bodyguard. My father works for the government, but even they don’t know enough about what the implants can do to manage my care. So everything went on SymboGen’s bill, and the corporation kept learning about what their tapeworms can do, while I kept getting the care I needed if I wanted to keep breathing. Breathing was nice. It was one of the first things I remembered discovering on my own, and I wanted to keep doing it for as long as possible.

Even with SymboGen looking out for me, we’d had our share of close calls. Since my accident I’d gone into full anaphylactic shock multiple times, for reasons I still didn’t fully understand. The first time had corresponded with a course of antiparasitics provided by SymboGen. They were intended to help me pass my old implant—a pretty way of saying “they were supposed to kill my tapeworm and force it out of my body”—and they’d nearly killed me, too. The second and third attacks had come out of nowhere, and the attack after that had corresponded with another course of antiparasitics, different ones.

What mattered to me was that I’d nearly died each time. Without SymboGen, I would have died. I needed to remember that. No matter how much I hated the therapists and the tests and everything else, I owed my life to SymboGen.

I looked back at Dr. Morrison’s office before walking down the street to the empty bus stop. I sat down on the bench and settled in to wait. I’m patient. I’m rarely in a hurry. And I don’t drive.

Patience may be something I have in abundance, but punctuality is not. My shift at the Cause for Paws animal center was supposed to start at four o’clock. Thanks to my missing the bus—again—and having to wait for the next one—again—it was already almost five when I came charging through the door.

“I’m sorry!” I called. I shrugged off my brown leather messenger bag and hung it next to the door, where it looked dull and out of place next to Tasha’s rainbow crochet purse and Will’s electric red backpack. In an organization made up of eccentrics and chronic do-gooders, the girl with the unique medical history is the boring one.

The door slammed behind me. I flinched.

“I’m sorry,” I repeated more quietly to Tasha, who was standing next to the coffee machine with an amused expression on her face.

“You’re sorry?” she asked. “Really? You’re late, and you’re sorry about it? Truly this is unprecedented in the annals of our humble shelter. I’ll mark the calendars.”

I stuck my tongue out at her.

“Did the bad psychologist try to tell you that you were crazy again?” asked Tasha, seemingly unperturbed. Perturbing Tasha was practically impossible. She was the kind of girl who would probably greet Godzilla while he was attacking downtown by asking whether he’d ever considered adopting a kitten to help him with his obvious stress disorder. “You can tell your Auntie Tasha about it. I swear I’m not a SymboGen plant reporting all your actions back to the corporation.”

“You’re a jerk,” I said mildly, and grabbed my apron. “Come on. Scale of one to murder, how mad is Will over the whole ‘late’ thing?”

“Will isn’t mad a

[The recording is crisp enough to look like a Hollywood film, too polished to be real. The lab is something out of a science fiction movie, all pristine white walls and gleaming glass and steel equipment. Only one thing in this scene is fully believable: the woman standing in front of the mass spectrometer, her wavy blonde hair pulled into a ponytail, a broad smile on her face. She is pretty, with a classic English bone structure and the sort of pale complexion that speaks less to genetics and more to being the type of person who virtually never goes outside. There is a petri dish in her blue-gloved hand.]

DR. CALE: Doctor Shanti Cale, Diphyllobothrium symbogenesis viability test thirty-seven. We have successfully matured eggs in a growth medium consisting of seventy percent human cells, thirty percent biological slurry. A full breakdown of the slurry can be found in the appendix to my latest progress report. The eggs appear to be viable, but we have not yet successfully induced hatching in any of the provided growth mediums. Upon consultation with Doctor Banks, I received permission to pursue other tissue sources.

[She walks to the back of the room, where a large, airlock-style door has been installed. The camera follows her through the airlock, and into what looks very much like an operating theater. Two men are waiting there, faces covered by surgical masks. Dr. Cale pauses long enough to put down her petri dish and put on a mask of her own.]

DR. CALE: The subject was donated to our lab by his wife, following the accident which left him legally brain-dead. For confirmation that the subject was obtained legally, please see the medical power of attorney attached to my latest progress report.

[The movement of her mask indicates a smile.]

DR. CALE: Well. Quasi-legally.

[Dr. Cale crosses to the body. Its midsection has been surrounded by a sterile curtain; the face is obscured by life support equipment, and by the angle of the shot. She pulls back the curtain to reveal the gleaming interior of the man’s sliced-open abdomen. The skin has been peeled back, and the blood has been suctioned away, revealing a wide array of colors. Liver brown, intestinal green and glistening white, and the smooth pink sac of the stomach. Calmly, she reaches into the man’s body, pushing organs aside until the surface of the small intestine is revealed.]

DR. CALE: Scalpel.

[One of the masked men passes her the requested tool. She takes it, pressing down against the man’s intestine. He does not move. Her hand does not tremble.]

DR. CALE: I am not following strict sterile protocol, in part because infection is not a risk. The subject’s immune system has been supplemented. D. symbogenesis eggs were introduced to the subject’s system six days ago, fed into his body along with the nutrient paste we have been using to preserve basic biological functions.

[The surface of the intestine splits, spilling a thin film of brownish liquid over the surrounding organs. Dr. Cale ignores it as she sets the scalpel aside and thrusts her hand into the man’s body. He still does not move as she digs through his small intestine. When she finally retracts her hand, she is clutching something. She pulls down her mask with her free hand and directs a beatific smile toward the camera.]

DR. CALE: I am pleased to report that we have multiple fully-formed proglottids present in the subject’s body, as well as some partial strobila.

[She holds out her hand. The camera zooms in on the white specks writhing against her gloved fingers.]

DR. CALE: D. symbogenesis is capable of maturing when cultured inside a living human host. Ladies and gentlemen… at long last, it’s alive.

[The film ends there. There are no notes in Dr. Cale’s progress reports relating to the eventual fate, or original identity, of the first human subject used to culture D. symbogenesis. The medical power of attorney referenced in the recording has never come to light.]

[End report.]

June 23, 2021: Time stamp, 13:17.

This is not the first thing I remember.

This is the first thing that I was told to remember; this is the memory that has been created for me by the hands and eyes and words of others. The first thing I remember has no need for hands, or eyes, or words. It has no need for others. It only needs the dark and the warm and the distant, constant sound of drums. The first thing I remember is paradise.

This is not the first thing I remember. But this is the first thing you will need to know.

Sally Mitchell was dying.

She was up against an army—an army that had begun with paramedics, moved on to doctors, and finally, to complicated life support machines that performed their function with passionless efficiency—but none of that seemed to make any difference. She had always been determined, and now, she was determined to die. Silently, and despite everyone’s best efforts, she was slipping further and further away.

It was not a swift process. Every cell in her body, damaged and undamaged alike, fought to retain cohesion. They struggled to pull in oxygen and force out the toxins that continued to build in her tissues and bloodstream. Her kidney function had been severely impaired in the accident, and waste chemicals had ceased to be automatically eliminated. She no longer responded in any meaningful way to external stimuli. Once she was removed from the machines that labored to keep her body functional, her life would come to an end in very short order.

Sally Mitchell existed in a state of living death, sustained by technology, but slipping away all the same.

Her hospital room was crowded—unusually so, for a woman standing in death’s doorway, but her doctor had hoped that by bringing her family to see her, he could better plead his case for taking her off life support. The damage from the accident had been too great. Tests had shown that Sally herself—the thinking, acting girl they remembered—was gone. “Clinical brain death” was the term he used, over and over again, trying to make them understand. Sally was gone. Sally was not coming back. And if they kept her on artificial life support for much longer, more of her organs would begin to shut down, until there was nothing left. If her family approved the procedures to harvest her organs now, her death could mean life for others. By pairing her organs with splices taken from her SymboGen implant, the risks of rejection could be reduced to virtually nothing. Dozens of lives could be saved, and all her family had to do was approve. All her family had to do was let her go.

All they had to do was admit that she was never waking up.

Sally Mitchell opened her eyes.

The ceiling was so white it burned, making her eyes begin to water in a parody of tears. She stared up at it for almost a minute, unable to process the message she was getting from her nerves. The message wanted her to close her eyes. Another part of her brain awakened, explaining what the burning sensation in her retinas meant.

Sally closed her eyes.

The doctor was still pleading with her family, cajoling and comforting them in turn as he explained what would happen next if they agreed to have Sally declared legally dead. His voice was no more or less compelling than the buzz of the machines around her. None of his words meant anything to her, and so she dismissed them as unimportant stimuli in a world that was suddenly full of unimportant stimuli. She focused instead on getting her eyes to open again. She wanted to see the white ceiling. It was… interesting.

The second time Sally opened her eyes, it was easier. Blinking came after that, and then the realization that she could breathe—her body reminded her of breathing, of the movement that it required, the pulling in of air through the nose, the expelling of air through the mouth. The respirator that was supposed to be handling the breathing process began beeping shrilly, confused in its mechanical way by her sudden involvement. The stimulus from the man in the ceiling-colored coat became more important as it grew louder, hurting her ears.

Sally sat up.

More machines started to beep. Sally winced, and then blinked, surprised by her own automatic reaction. She winced again, this time on purpose. The man in the ceiling-colored coat stared at her and said something she didn’t understand. She looked blankly back at him. Then the other people in the room started making noise, as shrill and confused as the machines around her, and one of them flung herself onto the bed, putting her arms around Sally and making a strange sound in her throat, like she was choking.

More people came into the room. The machines stopped making noise, but the people kept on doing it, making sounds she would learn were called “words,” asking questions she didn’t have answers for, and meanwhile, the body lived. The cells began to heal as the organs, one by one, resumed the jobs they had tried to abandon.

Sally Mitchell was going to live. Everything else was secondary.

Dark.

Always the dark, warm, hot warm, the hot warm dark, and the distant sound of drumming. Always the hot warm dark and the drums, the comforting drums, the drums that define the world. It is comfortable here. I am comfortable here. I do not want to leave again.

Dr. Morrison looked up from my journal and smiled. He always showed too many teeth when he was trying to be reassuring, stretching his lips so wide that he looked like he was getting ready to lean over and take a bite of my throat.

“I wish you wouldn’t smile at me like that,” I said. My skin was knotting itself into lumps of gooseflesh. I forced myself to sit still, refusing to give him the pleasure of seeing just how uncomfortable he made me.

For a professional therapist, Dr. Morrison seemed to take an unhealthy amount of joy in making me twitch. “Like what, Sally?”

“With the teeth,” I said, and shuddered. I don’t like teeth. I liked Dr. Morrison’s teeth less than most. If he smiled too much, I was going to wind up having another one of those nightmares, the ones where his smile spread all the way around his head and met at the back of his neck. Once that happened, his skull would spread open like a flower, and the mouth hidden behind his smile—his real mouth—would finally be revealed.

Crazy dreams, right? It was only appropriate, I guess. I was seeing him because I was a crazy, crazy girl. At least, that’s what the people who would know kept telling me, and it wasn’t like I could tell them any different. They were the ones who went to college and got degrees in are-you-crazy. I was just a girl who had to be reminded of her own name.

“We’ve discussed your odontophobia before, Sally. There’s no clinical reason for you to be afraid of teeth.”

“I’m not afraid of teeth,” I snapped. “I just don’t want to look at them.”

Dr. Morrison stopped smiling and shook his head, leaning over to jot something on his ever-present notepad. He didn’t bother hiding it from me anymore. He knew I couldn’t read it without taking a lot more time than I had. “You understand what this dream is telling us, don’t you?” His tone was as poisonously warm as his too-wide smile had been.

“I don’t know, Dr. Morrison,” I answered. “Why don’t you tell me, and we’ll see if we can come to a mutual conclusion?”

“Now, Sally, you know that dream interpretation doesn’t work that way,” he said, voice turning lightly chiding. I was being a smart-ass. Again. Dr. Morrison didn’t like that, which was fine by me, since I didn’t like Dr. Morrison. “Why don’t you tell me what the dream means to you?”

“It means I shouldn’t eat leftover spaghetti after midnight,” I said. “It means I feel guilty about forgetting to save yesterday’s bread for the ducks. It means I still don’t understand what irony is, even though I keep asking people to explain it. It means—”

He cut me off. “You’re dreaming about the coma,” he said. “Your mind is trying to cope with the blank places that remain part of your inner landscape. To some degree, you may even be longing to go back to that blankness, to a time when Sally Mitchell could be anything.”

The implication that the person Sally Mitchell became—namely, me—wasn’t good enough for my subconscious mind stung, but I wasn’t going to let him see that. “Wow. You really think that’s what the dream’s about?”

“Don’t you?”

I didn’t answer.

This was my last visit before my six-month check-in with the staff at SymboGen. Dr. Morrison would be turning in his recommendations before that, and the last thing I wanted to do was give him an excuse to recommend we go back to meeting twice a week, or even three times a week, like we had when I first started seeing him. I didn’t want to be adjusted to fit some model of the “psychiatric norm” drawn up by doctors who’d never met me and didn’t know my situation. I was tired of putting up with Dr. Morrison’s clumsy attempts to force me into that mold. We both knew he was only doing it because he hoped to write a book once SymboGen’s media blackout on my life was finally lifted. The Curing of Sally Mitchell. He’d make a mint.

Even more, I was tired of the way he always looked at me out of the corner of his eye, like I was going to flip out and start stabbing people. Then again, maybe he was right about that, on some level. There was no time when I felt more like stabbing people than immediately after one of our sessions.

“The imagery is crude, even childish. Clearly, you’re regressing in your sleep, returning to a time before you had so many things to worry about. I know it’s been hard on you, relearning everything about yourself. So much has changed in the last six years.” Dr. Morrison flipped to the next page in my journal, smiling again. It looked more artificial, and more dangerous, than ever. “How are your headaches, Sally? Are they getting any better?”

I bared my own teeth at him as I lied smoothly, saying, “I haven’t had a headache in weeks.” It helped if I reminded myself that I wasn’t totally lying. I wasn’t having the real banger migraines anymore, the ones that made me feel like it would have been a blessing if I’d died in the accident. All I got anymore were the little gnawing aches at my temples, the ones where it felt like my skull was shrinking. Those went away if I spent a few hours lying down in a dark room. They were nothing the doctor needed to be concerned about.

“You know, Sally, I can’t help you if you won’t let me.”

He kept using my name because it was supposed to help us build rapport. It was having the opposite effect. “It’s Sal now, Doctor,” I said, keeping my voice as neutral as I could. “I’ve been going by Sal for more than three years.”

“Ah, yes. Your continued efforts to distance yourself from your pre-coma identity.” He flipped to another page in my journal, quickly enough that I could tell he’d been waiting for the opportunity to drop this little bomb into the conversation. I braced myself, and he read:

Had another fight with parents last night. Want to move out, have own space, maybe find out if ready to move in with Nathan. They said wasn’t ready. Why not? Because Sally wasn’t ready? I am not her. I am me.

I will never be her again.

He lowered the book, looking at me expectantly. I looked back, and for almost a minute the two of us were locked in a battle of wills that had no possible winner, only a different order of losing. He wanted me to ask for his help. He wanted to heal me and turn me back into a woman I had no memory of being. I wanted him to let me be who I was, no matter how different I had become. Neither of us was getting what we wanted.

Finally, he broke. “This shows a worrisome trend toward disassociation, Sally. I’m concerned that—”

“Sal,” I said.

Dr. Morrison stopped, frowning at me. “What did you say?”

“I said, Sal, as in, ‘my name is.’ I’m not Sally anymore. It’s not disassociation if I say I’m not her, because I don’t remember her at all. I don’t even know who she is. No one will tell me the whole story. Everyone tries so hard not to say anything bad about her to me, even though I know better. It’s like they’re all afraid I’m pretending, like this is some big trick to catch them out.”

“Is it?” Dr. Morrison leaned forward. His smile was suddenly gone, replaced by an expression of predatory interest. “We’ve discussed your amnesia before, Sally. No one can deny that you sustained extensive trauma in the accident, but amnesia as extensive and prolonged as yours is extremely rare. I’m concerned there may be a mental block preventing your accessing your own memories. When this block inevitably degrades—if you’ve been feigning amnesia this whole time, it would be a great relief in some ways. It would indicate much better chances for your future mental stability.”

“Wouldn’t faking total memory loss for six years count as a sort of pathological lying, and prove I needed to stay in your care until I stopped doing it?” I asked.

Dr. Morrison frowned, leaning back again. “So you continue to insist that you have no memory prior to the accident.”

I shrugged. “We’ve been over this before. I have no memory of the accident itself. The first thing I remember is waking up in the hospital, surrounded by strangers.”

One of them had screamed and fainted when I sat up. I didn’t learn until later that she was my mother, or that she had been there—along with my father, my younger sister, and my boyfriend—to talk to my doctors about unplugging the life support systems keeping my body alive. My sister, Joyce, had just stared at me and started to cry. I didn’t understand what she was doing. I couldn’t remember ever having seen someone cry before. I couldn’t remember ever having seen a person before. I was a blank slate.

Then Joyce was throwing herself across me, and the feeling of pressure had been surprising enough that I hadn’t pushed her away. My father helped my mother off the floor, and they both joined my sister on the bed, all of them crying and talking at once.

It would be months before I understood English well enough to know what they were saying, much less to answer them. By the time I managed my first sentence—“Who I?”—the boyfriend was long gone, having chosen to run rather than spend the rest of his life with a potentially brain-damaged girlfriend. The fact that I still hadn’t recovered my memory six years later implied that he’d made the right decision. Even if he’d decided to stick around, there was no guarantee we’d have liked each other, much less loved each other. Leaving me was the best thing he could have done, for either one of us.

After all, I was a whole new person now.

“We were discussing your family. How are things going?”

“We’ve been working through some things,” I said. Things like their overprotectiveness, and the way they refused to treat me like a normal human being. “I think we’re doing pretty good. But thanks for asking.”

My mother thought I was a gift from God, since she hadn’t expected me to wake up. She also thought I would turn back into Sally any day, and was perpetually, politely confused when I didn’t. My father didn’t invoke God nearly as much, but he did like to say, frequently, that everything happens for a reason. Apparently, he and Sally hadn’t had a very good relationship. He and I were doing substantially better. It helped that we were both trying as hard as we could, because we both knew that things were tenuous.

Joyce was the only one who’d been willing to speak to me candidly, although she only did it when she was drunk. She didn’t drink often; I didn’t drink at all. “You were a real bitch, Sal,” she’d said. “I like you a lot better now. If you start turning into a bitch again, I’ll cut your brake lines.”

It was totally honest. It was totally sincere. The night she said that to me was the night I realized that I might not remember my sister, but I definitely loved her. On the balance of things, maybe I’d gotten off lightly. Maybe losing my memory was a blessing.

Dr. Morrison’s disappointment visibly deepened. Clearing his throat, he flipped to another point in my journal, and read:

Last night I dreamt I was swimming through the hot warm dark, just me and the sound of drums, and there was nothing in the world that could frighten me or hurt me or change the way things were.

Then there was a tearing, ripping sound, and the drums went quiet, and everything was pain, pain, PAIN. I never felt pain like that before, and I tried to scream, but I couldn’t scream—something stopped me from screaming. I fled from the pain, and the pain followed me, and the hot warm dark was turning cold and crushing, until it wasn’t comfort, it was death. I was going to die. I had to run as fast as I could, had to find a new way to run, and the sound of drums was fading out, fading into silence.

If I didn’t get to safety before the drums stopped, I was never going to get to safety at all. I had to save the drums. The drums were everything.

He looked up. “That’s an odd amount of importance to place on a sound, don’t you think? What do the drums represent to you, Sally?”

“I don’t know. It was just a dream I had.” It was a dream I had almost every night. I only wrote it down because Nathan said that maybe Dr. Morrison would stop pushing quite so hard if he felt like he had something to interpret. Well, he had something to interpret, and it wasn’t making him back off. If anything, it was doing the opposite. I made a mental note to smack my boyfriend next time I saw him.

“Dreams mean things. They’re our subconscious trying to communicate with us.”

The smug look on his face was too much. “You’re about to tell me I’m dreaming about being in the womb, aren’t you? That’s what you always say when you want to sound impressive.”

His smug expression didn’t waver.

“Look, I can’t be dreaming about being in the womb, since that would require remembering anything before the accident, and I don’t.” I struggled to keep my tone level. “I’m having nightmares based on the things people have told me about my accident, that’s all. Everything is great, and then suddenly everything goes to hell? It doesn’t take a genius to guess that the drums are my heart beating. I know they lost me twice in the ambulance, and that the head trauma was so bad they thought I was actually brain-dead. If I hadn’t woken up when I did, they would have pulled the plug. I mean, maybe I don’t like the girl they say I was, but at least she didn’t have to go through physical therapy, or relearn the English language, or relearn everything about living a normal life. Do I feel isolated from her? You bet I do. Lucky bitch died that day, at least as long as her memories stay gone. I’m just the one who has to deal with all the paperwork.”

Dr. Morrison raised an eyebrow, looking nonplussed. Then he reached for his notepad. “Interesting,” he said.

Somehow I managed not to groan.

The rest of the session was as smooth as any of them ever were. Dr. Morrison asked questions geared to make me blow up again; I dodged them as best as I could, and bit the inside of my lip every time I felt like I might lose my cool. At the end of the hour, we were both disappointed. He was disappointed because I hadn’t done more yelling, and I was disappointed because I’d yelled in the first place. I hate losing my temper. Even more, I hate losing it in front of people like Dr. Morrison. Being Sally Mitchell sucks sometimes. There’s always another doctor who wants a question answered and thinks the best way to do it is to poke a stick through the bars of my metaphorical cage. I didn’t volunteer to be the first person whose life was saved by a tapeworm. It just happened.

I have to remind myself of that whenever things get too ridiculous: I am alive because of a genetically engineered tapeworm. Not a miracle; God was not involved in my survival. They can call it an “implant” or an “Intestinal Bodyguard,” with or without that damn trademark, but the fact remains that we’re talking about a tapeworm. A big, ugly, blind, parasitic invertebrate that lives in my small intestine, where it naturally secretes a variety of useful chemicals, including—as it turns out—some that both stimulate brain activity and clean toxic byproducts out of blood.

The doctors were as surprised by that as I was. They’re still investigating whether the tapeworm’s miracle drugs are connected to my memory loss. Frankly, I neither care nor particularly want to know. I’m happy with who I’ve become since the accident.

Dr. Morrison’s receptionist smiled blandly as I signed out. SymboGen required physically-witnessed time stamps for my sessions. I smiled just as blandly back. It was the safest thing to do. I’d tried being friendly during my first six months of sessions, until I learned that I was basically under review from the time I stepped through the door. Anything I did while inside the office could be entered into my file. Since those first six months included more than a few crying jags in the lobby, they were enough to buy me even more therapy.

“Have a nice day, Miss Mitchell,” said the receptionist, taking back her clipboard. “See you next week.”

I smiled at her again, sincerely this time. “Only if my doctors agree with whatever assessment Dr. Morrison comes up with, instead of agreeing with me. If there is any justice in this world, you’ll never be seeing me again.”

Maybe the comment was ill-advised, but it still felt good to see her perfectly made-up eyes widen in shock. She was still gaping at me as I turned back to the door and made my way quickly out of the office, into the sweet freedom of the afternoon air.

One good thing about being the first—and thus far, only—person to be saved from certain death by the SymboGen Intestinal Bodyguard: I wasn’t paying for a penny of my medical care, and neither were my parents. Instead, the corporation paid for everything, and got running updates from my various doctors, all of whom had release forms on file making it legal for them to give my medical information to SymboGen. It sucked from a privacy standpoint, but it was better than dying.

SymboGen developed the Intestinal Bodyguard. My father works for the government, but even they don’t know enough about what the implants can do to manage my care. So everything went on SymboGen’s bill, and the corporation kept learning about what their tapeworms can do, while I kept getting the care I needed if I wanted to keep breathing. Breathing was nice. It was one of the first things I remembered discovering on my own, and I wanted to keep doing it for as long as possible.

Even with SymboGen looking out for me, we’d had our share of close calls. Since my accident I’d gone into full anaphylactic shock multiple times, for reasons I still didn’t fully understand. The first time had corresponded with a course of antiparasitics provided by SymboGen. They were intended to help me pass my old implant—a pretty way of saying “they were supposed to kill my tapeworm and force it out of my body”—and they’d nearly killed me, too. The second and third attacks had come out of nowhere, and the attack after that had corresponded with another course of antiparasitics, different ones.

What mattered to me was that I’d nearly died each time. Without SymboGen, I would have died. I needed to remember that. No matter how much I hated the therapists and the tests and everything else, I owed my life to SymboGen.

I looked back at Dr. Morrison’s office before walking down the street to the empty bus stop. I sat down on the bench and settled in to wait. I’m patient. I’m rarely in a hurry. And I don’t drive.

Patience may be something I have in abundance, but punctuality is not. My shift at the Cause for Paws animal center was supposed to start at four o’clock. Thanks to my missing the bus—again—and having to wait for the next one—again—it was already almost five when I came charging through the door.

“I’m sorry!” I called. I shrugged off my brown leather messenger bag and hung it next to the door, where it looked dull and out of place next to Tasha’s rainbow crochet purse and Will’s electric red backpack. In an organization made up of eccentrics and chronic do-gooders, the girl with the unique medical history is the boring one.

The door slammed behind me. I flinched.

“I’m sorry,” I repeated more quietly to Tasha, who was standing next to the coffee machine with an amused expression on her face.

“You’re sorry?” she asked. “Really? You’re late, and you’re sorry about it? Truly this is unprecedented in the annals of our humble shelter. I’ll mark the calendars.”

I stuck my tongue out at her.

“Did the bad psychologist try to tell you that you were crazy again?” asked Tasha, seemingly unperturbed. Perturbing Tasha was practically impossible. She was the kind of girl who would probably greet Godzilla while he was attacking downtown by asking whether he’d ever considered adopting a kitten to help him with his obvious stress disorder. “You can tell your Auntie Tasha about it. I swear I’m not a SymboGen plant reporting all your actions back to the corporation.”

“You’re a jerk,” I said mildly, and grabbed my apron. “Come on. Scale of one to murder, how mad is Will over the whole ‘late’ thing?”

“Will isn’t mad a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved