- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

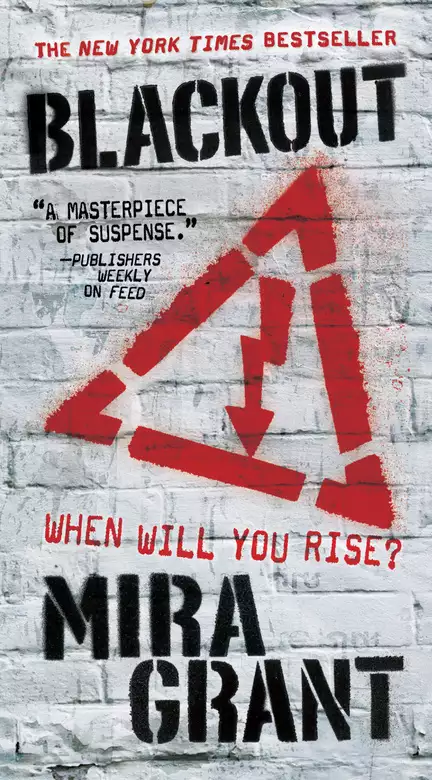

The explosive conclusion to the Newsflesh trilogy from New York Times bestseller Mira Grant.

The year was 2014. The year we cured cancer. The year we cured the common cold. And the year the dead started to walk. The year of the Rising.

The year was 2039. The world didn't end when the zombies came, it just got worse. Georgia and Shaun Mason set out on the biggest story of their generation. The uncovered the biggest conspiracy since the Rising and realized that to tell the truth, sacrifices have to be made.

Now, the year is 2041, and the investigation that began with the election of President Ryman is much bigger than anyone had assumed. With too much left to do and not much time left to do it in, the surviving staff of After the End Times must face mad scientists, zombie bears, rogue government agencies-and if there's one thing they know is true in post-zombie America, it's this:

Things can always get worse.

BLACKOUT is the conclusion to the epic trilogy that began in the Hugo-nominated FEED and the sequel, DEADLINE.

Newsflesh

Feed

Deadline

Blackout

For more from Mira Grant, check out:

Parasitology

Parasite

Symbiont

Chimera

Newsflesh Short Fiction

Apocalypse Scenario #683: The Box

Countdown

San Diego 2014: The Last Stand of the California Browncoats

How Green This Land, How Blue This Sea

The Day the Dead Came to Show and Tell

Please Do Not Taunt the Octopus

Release date: May 22, 2012

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 672

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Blackout

Mira Grant

My story ended where so many stories have ended since the Rising: with a man—in this case, my adoptive brother and best friend, Shaun—holding a gun to the base of my skull as the virus in my blood betrayed me, transforming me from a thinking human being into something better suited to a horror movie.

My story ended, but I remember everything. I remember the cold dread as I watched the lights on the blood test unit turn red, one by one, until my infection was confirmed. I remember the look on Shaun’s face when he realized this was it—it was really happening, and there wasn’t going to be any clever third act solution that got me out of the van alive.

I remember the barrel of the gun against my skin. It was cool, and it was soothing, because it meant Shaun would do what he had to do. No one else would get hurt because of me.

No one but Shaun.

This was something we’d never planned for. I always knew that one day he’d push his luck too far, and I’d lose him. We never dreamed that he would be the one losing me. I wanted to tell him it would be okay. I wanted to lie to him. I remember that: I wanted to lie to him. And I couldn’t. There wasn’t time, and even then, I didn’t have it in me.

I remember starting to write. I remember thinking this was it; this was my last chance to say anything I wanted to say to the world. This was the thing I was going to be judged on, now and forever. I remember feeling my mind start to go. I remember the fear.

I remember the sound of Shaun pulling the trigger.

I shouldn’t remember anything after that. That’s where my story ended. Curtain down, save file, that’s a wrap. Once the bullet hits your spinal cord, you’re done; you don’t have to worry about this shit anymore. You definitely shouldn’t wake up in a windowless, practically barren room that looks suspiciously like a CDC holding facility, with no one to talk to but some unidentified voice on the other side of a one-way mirror.

The bed where I’d woken up was bolted to the floor, and so was the matching bedside table. It wouldn’t do to have the mysteriously resurrected dead journalist throwing things at the mirror that took up most of one wall. Naturally, the wall with the mirror was the only wall with a door—a door that refused to open. I’d tried waving my hands in front of every place that might hold a motion sensor, and then I’d searched for a test panel in the vain hope that checking out clean would make the locks let go and release me.

There were no test panels, or screens, or ocular scanners. There wasn’t anything inside that seemed designed to let me out. That was chilling all by itself. I grew up in a post-Rising world, one where blood tests and the threat of infection are a part of daily life. I’m sure I’d been in sealed rooms without testing units before. I just couldn’t remember any.

The room lacked something else: clocks. There was nothing to let me know how much time had passed since I woke up, much less how much time had passed before I woke up. There’d been a voice from the speaker above the mirror, an unfamiliar voice asking my name and what the last thing I remembered was. I’d answered him—“My name is Georgia Mason. What the fuck is going on here?”—and he’d gone away without answering my question. That might have been ten minutes ago. It might have been ten hours ago. The lights overhead glared steady and white, not so much as flickering as the seconds went slipping past.

That was another thing. The overhead lights were industrial fluorescents, the sort that have been popular in medical facilities since long before the Rising. They should have been burning my eyes like acid… and they weren’t.

I was diagnosed with retinal Kellis-Amberlee when I was a kid, meaning that the same disease that causes the dead to rise had taken up permanent residence in my eyeballs. It didn’t turn me into a zombie—retinal KA is a reservoir condition, one where the live virus is somehow contained inside the body. Retinal KA gave me extreme light sensitivity, excellent night vision, and a tendency to get sickening migraines if I did anything without my sunglasses on.

Well, I wasn’t wearing sunglasses, and it wasn’t like I could dim the lights, but my eyes still didn’t hurt. All I felt was thirst, and a vague, gnawing hunger in the pit of my stomach, like lunch might be a good idea sometime soon. There was no headache. I honestly couldn’t decide whether or not that was a good sign.

Anxiety was making my palms sweat. I scrubbed them against the legs of my unfamiliar white cotton pajamas. Everything in the room was unfamiliar… even me. I’ve never been heavy—a life spent running after stories and away from zombies doesn’t encourage putting on weight—but the girl in the one-way mirror was thin to the point of being scrawny. She looked like she’d be easy to break. Her hair was as dark as mine. It was also too long, falling past her shoulders. I’ve never allowed my hair to get that long. Hair like that is a passive form of suicide when you do what I do for a living. And her eyes…

Her eyes were brown. That, more than anything else, made it impossible to think of her face as my own. I don’t have visible irises. I have pupils that fill all the space not occupied by sclera, giving me a black, almost emotionless stare. Those weren’t my eyes. But my eyes didn’t hurt. Which meant either those were my eyes, and my retinal KA had somehow been cured, or Buffy was right when she said the afterlife existed, and this was hell.

I shuddered, looking away from my reflection, and resumed what was currently my main activity: pacing back and forth and trying to think. Until I knew whether I was being watched, I had to think quietly, and that made it a hell of a lot harder. I’ve always thought better when I do it out loud, and this was the first time in my adult life that I’d been anywhere without at least one recorder running. I’m an accredited journalist. When I talk to myself, it’s not a sign of insanity; it’s just my way of making sure I don’t lose important material before I can write it down.

None of this was right. Even if there was some sort of experimental treatment to reverse amplification, someone would have been there to explain things to me. Shaun would have been there. And there it was, the reason I couldn’t believe any of this was right: I remembered him pulling the trigger. Even assuming it was a false memory, even assuming it never happened, why wasn’t he here? Shaun would move Heaven and Earth to reach me.

I briefly entertained the idea that he was somewhere in the building, forcing the voice from the intercom to tell him where I was. Regretfully, I dismissed it. Something would have exploded by now if that were true.

“Goddammit.” I scowled at the wall, turned, and started in the other direction. The hunger was getting worse, and it was accompanied by a new, more frustrating sensation. I needed to pee. If someone didn’t let me out soon, I was going to have a whole new set of problems to contend with.

“Run the timeline, George,” I said, taking some comfort in the sound of my voice. Everything else might have changed, but not that. “You were in Sacramento with Rick and Shaun, running for the van. Something hit you in the arm. One of those syringes like they used at the Ryman farm. The test came back positive. Rick left. And then… then…” I faltered, having trouble finding the words, even if there was no one else to hear them.

Everyone who grew up after the Rising knows what happens when you come into contact with the live form of Kellis-Amberlee. You become a zombie, one of the infected, and you do what every zombie exists to do. You bite. You infect. You kill. You feed. You don’t wake up in a white room, wearing white pajamas and wondering how your brother was able to shoot you in the neck without even leaving a scar.

Scars. I wheeled and stalked back to the mirror, pulling the lid on my right eye open wide. I learned how to look at my own eyes when I was eleven. That’s when I got my first pair of protective contacts. That’s also when I got my first visible retinal scarring, little patches of tissue scorched beyond recovery by the sun. We caught it in time to prevent major vision loss, and I got a lot more careful. The scarring created small blind spots at the center of my vision. Nothing major. Nothing that interfered with fieldwork. Just little spots.

My pupil contracted to almost nothing as the light hit it. The spots weren’t there. I could see clearly, without any gaps.

“Oh.” I lowered my hand. “I guess that makes sense.”

I paused, feeling suddenly stupid as that realization led to another. When I first woke up, the voice from the intercom told me all I had to do was speak, and someone would hear me. I looked up at the speaker. “A little help here?” I said. “I need to pee really bad.”

There was no response.

“Hello?”

There was still no response. I showed my middle finger to the mirror before turning and walking back to the bed. Once there, I sat and settled into a cross-legged position, closing my eyes. And then I started waiting. If anyone was watching me—and someone had to be watching me—this might be a big enough change in my behavior to get their attention. I wanted their attention. I wanted their attention really, really badly. Almost as badly as I wanted a personal recorder, an Internet connection, and a bathroom.

The need for a bathroom crept slowly higher on the list, accompanied by the need for a drink of water. I was beginning to consider the possibility that I might need to use a corner of the room as a lavatory when the intercom clicked on. A moment later, a new voice, male, like the first one, spoke: “Miss Mason? Are you awake?”

“Yes.” I opened my eyes. “Do I get a name to call you by?”

He ignored my question like it didn’t matter. Maybe it didn’t, to him. “I apologize for the silence. We’d expected a longer period of disorientation, and I had to be recalled from elsewhere in the building.”

“Sorry to disappoint you.”

“Oh, we weren’t disappointed,” said the voice. He had the faintest trace of a Midwestern accent. I couldn’t place the state. “I promise, we’re thrilled to see you up and coherent so quickly. It’s a wonderful indicator for your recovery.”

“A glass of water and a trip to the ladies’ room would do more to help my recovery than apologies and evasions.”

Now the voice sounded faintly abashed. “I’m sorry, Miss Mason. We didn’t think… just a moment.” The intercom clicked off, leaving me in silence once again. I stayed where I was, and kept waiting.

The sound of a hydraulic lock unsealing broke the quiet. I turned to see a small panel slide open above the door, revealing a red light. It turned green and the door slid smoothly open, revealing a skinny, nervous-looking man in a white lab coat, eyes wide behind his glasses. He was clutching his clipboard to his chest like he thought it afforded him some sort of protection.

“Miss Mason? If you’d like to come with me, I’d be happy to escort you to the restroom.”

“Thank you.” I unfolded my legs, ignoring pins and needles in my calves, and walked toward the doorway. The man didn’t quite cringe as I approached, but he definitely shied back, looking more uneasy with every step I took. Interesting.

“We apologize for making you wait,” he said. His words had the distinct cadence of something recited by rote, like telephone tech support asking for your ID and computer serial number. “There were a few things that had to be taken care of before we could proceed.”

“Let’s worry about that after I get to the bathroom, okay?” I sidestepped around him, out into the hall, and found myself looking at three hospital orderlies in blue scrubs, each of them pointing a pistol in my direction. I stopped where I was. “Okay, I can wait for my escort.”

“That’s for the best, Miss Mason,” said the nervous man, whose voice I now recognized from the intercom. It just took a moment without the filtering speakers between us. “Just a necessary precaution. I’m sure you understand.”

“Yeah. Sure.” I fell into step behind him. The orderlies followed us, their aim never wavering. I did my best not to make any sudden moves. Having just returned to the land of the living, I was in no mood to exit it again. “Am I ever going to get something I can call you?”

“Ah…” His mouth worked soundlessly for a moment before he said, “I’m Dr. Thomas. I’ve been one of your personal physicians since you arrived at this facility. I’m not surprised you don’t remember me. You’ve been sleeping for some time.”

“Is that what the kids are calling it these days?” The hall was built on the model I’ve come to expect from CDC facilities, with nothing breaking the sterile white walls but the occasional door and the associated one-way mirrors looking into patient holding rooms. All the rooms were empty.

“You’re walking well.”

“It’s a skill.”

“How’s your head? Any disorientation, blurred vision, confusion?”

“Yes.” He tensed. I ignored it, continuing. “I’m confused about what I’m doing here. I don’t know about you, but I get twitchy when I wake up in strange places with no idea how I got there. Will I be getting some answers soon?”

“Soon enough, Miss Mason.” He stopped in front of a door with no mirror next to it. That implied that it wasn’t a patient room. Better yet, there was a blood test unit to one side. I never thought I’d be so happy for the chance to be jabbed with a needle. “We’ll give you a few minutes. If you need anything—”

“Using the bathroom, also a skill.” I slapped my palm down on the test panel. Needles promptly bit into the heel of my hand and the tips of my fingers. The light over the door flashed between red and green before settling on the latter. Uninfected. The door swung open. I stepped through, only to stop and scowl at the one-way mirror taking up most of the opposite wall. The door swung shut behind me.

“Cute,” I muttered. The need to pee was getting bad enough that I didn’t protest the situation. I glared at the mirror the entire time I was using the facilities, all but daring someone to watch me. See? I can pee whether you’re spying on me or not, you sick bastards.

Other than the mirror—or maybe because of the mirror—the bathroom was as standard-issue CDC as the hallway outside, with white walls, a white tile floor, and white porcelain fixtures. Everything was automatic, including the soap dispenser, and there were no towels; instead, I dried my hands by sticking them into a jet of hot air. It was one big exercise in minimizing contact with any surface. When I turned back to the door, the only things I’d touched were the toilet seat and the floor, and I was willing to bet that they were in the process of self-sterilization by the time I started washing my hands.

The blood test required to exit the bathroom was set into the door itself, just above the knob. It didn’t unlock until I checked out clean.

The three orderlies were waiting in the hall, with an unhappy Dr. Thomas between them and me. If I did anything bad enough to make them pull those triggers, the odds were good that he’d be treated as collateral damage.

“Wow,” I said. “Who did you piss off to get this gig?”

He flinched, looking at me guiltily. “I’m sure I don’t know what you mean.”

“Of course not. Thank you for bringing me to the bathroom. Now, could I get that water?” Better yet, a can of Coke. The thought of its acid sweetness was enough to make my mouth water. It’s good to know that some things never change.

“If you’d come this way?”

I gave the orderlies a pointed look. “I don’t think I have much of a choice, do you?”

“No, I suppose you don’t,” he said. “As I said, a precaution. You understand.”

“Not really, no. I’m unarmed. I’ve just passed two blood tests. I don’t understand why I need three men with guns covering my every move.” The CDC has been paranoid for years, but this was taking it to a new extreme.

Dr. Thomas’s reply didn’t help: “Security.”

“Why do people always say that when they don’t feel like giving a straight answer?” I shook my head. “I’m not going to make trouble. Please, just take me to the water.”

“Right this way,” he said, and started back the way we’d come.

There was a tray waiting for us on the bolted-down table in the room where I’d woken up. It held a plate with two pieces of buttered toast, a tumbler full of water, and wonder of wonders, miracle of miracles, a can of Coke with condensation beading on the sides. I made for the tray without pausing to consider how the orderlies might react to my moving faster than a stroll. None of them shot me in the back. That was something.

The first bite of toast was the best thing I’d ever tasted, at least until I took the second bite, and then the third. Finally, I crammed most of the slice into my mouth, barely chewing. I managed to resist the siren song of the Coke long enough to drink half the water. It tasted as good as the toast. I put down the glass, popped the tab on the can of soda, and took my first post-death sip of Coke. I was smart enough not to gulp it; even that tiny amount was enough to make my knees weak. That, and the caffeine rush that followed, provided the last missing piece.

Slowly, I turned to face Dr. Thomas. He was standing in the doorway, making notes on his clipboard. There were probably a few dozen video and audio recorders running, catching every move I made, but any good reporter will tell you that there’s nothing like real field experience. I guess the same thing applies to scientists. He lowered his pen when he saw me looking.

“How do you feel?” he asked. “Dizzy? Are you full? Did you want something besides toast? It’s a bit early for anything complicated, but I might be able to arrange for some soup, if you’d prefer that…”

“Mostly, what’d I’d prefer is having some questions answered.” I shifted the Coke from one hand to the other. If I couldn’t have my sunglasses, I guess a can of soda would have to do. “I think I’ve been pretty cooperative up to now. I also think that could change.”

Dr. Thomas looked uncomfortable. “Well, I suppose that will depend on what sort of questions you want to ask.”

“This one should be pretty easy. I mean, it’s definitely within your skill set.”

“All right. I can’t promise to know the answer, but I’m happy to try. We want you to be comfortable.”

“Good.” I looked at him levelly, missing my black-eyed gaze. It always made people so uncomfortable. I got more honest answers out of those eyes… “You said you were my personal physician.”

“That’s correct.”

“So tell me: How long have I been a clone?”

Dr. Thomas dropped his pen.

Still watching him, I raised my Coke, took a sip, and waited for his reply.

Subject 139b was bitten on the evening of June 24, 2041. The exact time of the bite was not recorded, but a period of no less than twenty minutes elapsed between exposure and initial testing. The infected individual responsible for delivering the bite was retrieved from the road. Posthumous analysis confirmed that the individual was heavily contagious, and had been so for at least six days, as the virus had amplified through all parts of the body.

Blood samples were taken from the outside of Subject 139b’s hand and sequenced to prove that they belonged to the subject. Analysis of these samples confirmed the infection. (For proof of live viral bodies in Subject 139b’s blood, see the attached file.) Amplification appears to have begun normally, and followed the established progression toward full loss of cognitive functionality. Samples taken from Subject 139b’s clothing confirm this diagnosis.

Subject 139b was given a blood test shortly after arriving at this facility, and tested clean of all live viral particles. Subject 139b was given a second test, using a more sensitive unit, and once again tested clean. After forty-eight hours of isolation, following standard Kellis-Amberlee quarantine procedures, it is my professional opinion that the subject is not now infected, and does not represent a danger to himself or others.

With God as my witness, Joey, I swear to you that Shaun Mason is not infected with the live state of Kellis-Amberlee. He should be. He’s not. He started to amplify, and he somehow fought the infection off. This could change everything… if we had the slightest fucking clue how he did it.

—Taken from an e-mail sent by Dr. Shannon Abbey to Dr. Joseph Shoji at the Kauai Institute of Virology, June 27, 2041.

Times like this make me think my mother was right when she told me I should aspire to be a trophy wife. At least that would have reduced the odds of my winding up hiding in a renegade virology lab, hunting zombies for a certifiable mad scientist.

Then again, maybe not.

—From Charming Not Sincere, the blog of Rebecca Atherton, July 16, 2041. Unpublished.

Shaun! Look out!”

Alaric’s shout came through my headset half a second before a hand grabbed my elbow, bearing down with that weird mixture of strength and clumsiness characteristic of the fully amplified. I yanked free, whirling to smack my assailant upside the head with my high-powered cattle prod.

A look of almost comic surprise crossed the zombie’s face as the electrified end of the cattle prod hit its temple. Then it fell. I kicked the body. It didn’t move. I hit it in the solar plexus with my cattle prod, just to be sure. Electricity has always been useful against zombies, since it confuses the virus that motivates them, but it turns out that when you amp the juice enough you can actually shut them down for short periods of time.

“Thanks for the heads-up,” I said, trusting the headset to pick me up. “I’ve got another dead boy down. Send the retrieval team to my coordinates.” I was already starting to scan the trees, looking for signs of movement—looking for something else that I could hit.

“Shaun…” There was a wary note in Alaric’s voice. I could practically see him sitting at his console, knotting his hands in his hair and trying not to let his irritation come through the microphone. I was his boss, after all, which meant he had to at least pretend to be respectful. Once in a while. “That’s your fourth catch of the night. I think that’s enough, don’t you?”

“I’m going for the record.”

There was a click as Becks plugged her own channel into the connection and snapped peevishly, “You’ve already got the record. Four catches in a night is twice what anyone else has managed, ever. Now please, please, come back to the lab.”

“What will you do if I don’t?” I asked. Nothing seemed to be moving, except for my infected friend, who twitched. I zapped him with the cattle prod again. The movement stopped.

“Two words, Shaun: tranquilizer darts. Now come back to the lab.”

I whistled. “That’s not playing fair. How about you promise to bake me chocolate chip cookies if I come back? That seems like a much better incentive.”

“How about you stop screwing around before you make me angry? Immune doesn’t mean immortal, you know. Now please.” The peevishness faded, replaced by pleading. “Just come home.”

She’s right, said George—or the ghost of George, anyway, the little voice at the back of my head that’s all I have left of my adopted sister. Some people say I have issues. I say those people need to expand their horizons, because I don’t have issues, I have the Library of Congress. You need to go back. This isn’t doing anybody any good.

“I don’t know,” I said. I used to be circumspect about talking to George. That was before I decided to go all the way insane. Madness is surprisingly freeing. “I mean, I’m having fun. Aren’t you the one who used to nag me to get my butt back into the field? Is this field enough for you?”

Shaun. Please.

My smile faded. “Fine. Whatever. If you want me to go back to the stupid lab, I’ll go back to the stupid lab. Happy now?”

No, said George. But it’s going to have to do.

I poked my latest catch one last time with the cattle prod. It didn’t react. I turned to stalk back through the trees to the ripped-up side road where the bike was parked. Gunshots sounded from the forest to my left. I paused. Silence followed them, rather than screaming. I nodded and started walking again. Maybe that seems callous, but I wasn’t the only one collecting virtual corpses for Dr. Abbey, the crazy renegade virologist who’d been sheltering us since we were forced off the grid. Most of her lab technicians were either ex-military or trained marksmen. They could take care of themselves, at least in the “killing stuff” department. I was less sure about bringing the zombies home alive. Fortunately for me, that was their problem, not mine.

Alaric’s sigh of relief made me jump. I’d almost forgotten that he and Becks were listening in from their cozy spot in the main lab. “Thank you for seeing sense.”

“Don’t thank me,” I said. “Thank George.”

Neither of them had anything to say to that. I hadn’t expected them to. I tapped the button on the side of my headset, killing the connection, and kept walking.

It had been just under a month since the world turned upside down. Some days, I was almost grateful to be waking up in an underground virology lab. Sure, most of the things it contained could kill me—including the head virologist, who I suspected of having fantasies about dissecting me so she could analyze my organs—but at least we knew what was going on. We had a place, if not a fully functional plan. That put us way ahead of the surviving denizens of North America’s Gulf Coast, who were still contending with something we’d never anticipated: an insect vector for Kellis-Amberlee.

A tropical storm had blown some brand-new strain of mosquito over from Cuba, one with a big enough bite to transmit the live virus to humans. No one had heard of an insect vector for Kellis-Amberlee before that day. The entire world had heard of it on the day after, as every place Tropical Storm Fiona touched discovered the true meaning of “storm damage.” The virus spread initially with the storm, and then started spreading on its own as the winds died down and the mosquitoes went looking for something to munch on. It was a genuine apocalypse scenario, the sort of thing that makes trained medical personnel shit their pants and call for their mommies. And it was really happening, and there wasn’t a damn thing we could do about it.

The worst part? Even if no one wanted to say it out loud, when you looked at the timing of everything going wrong—the way it all happened just as we started really prodding at the CDC’s sore spots—I thought there was a pretty good chance it wasn’t an accident. And that would mean it was our fault.

There was no one standing watch over the vehicles. That was sloppy; even if we cleared out the human infected, there was always the chance a zombie raccoon or something could take refuge under one of the collection vans and go for somebody’s ankles when they came back with the evening’s haul. I made a mental note to talk to Dr. Abbey about her tactical setup as I swung a leg over the bike. Then I put on my helmet—Becks was right, immune doesn’t mean immortal—and took off down the road.

See, here’s the thing. My name is Shaun Mason; I’m a journalist, I guess, even though right now all my posts are staying unpublished for security’s sake. I’m not technically wanted for anything. It’s just that places where I show up have a nasty tendency to get wiped off the map shortly after I get there, and that makes me a little gun-shy when it comes to telling people where I am. I think that’s understandable. Then again, I also think my dead sister talks to me, so what do I know?

About a year and a half ago—which feels like yesterday and an eternity at the same time—George and I applied to blog for Senator Peter Ryman’s presidential campaign, along with our friend Georgette “Buffy” Meissonier. Before that, I was your average gentleman Irwin, wanting nothing beyond a few dead things to poke with sticks and the opportunity to write up my adventures for an adoring populace. Pretty simple, right? The three of us had everything we needed to be happy. Only we didn’t know that, so when the chance to grab for glory came, we took it. We wanted to make history.

We made it, all right. We made it, Buffy and George became it, and I wound up as the last man standing, the one who has to avenge the glorious dead. All I know is that part wasn’t in the brochure.

The road smoothed as I got closer to our current home-sweet-home. Shady Cove, Oregon, has been deserted since the Rising, when the infected left the tiny community officially uninhabitable. We had to be careful about how visible we were, but Dr. Abbey had been sending her interns—interning for what, I didn’t know, since most universities don’t offer a degree in mad science—out at night to patch the worst of the potholes with a homebrewed asphalt substitute that looked just like the real thing.

Fixing the road was a mixed blessing. It could give away our location if someone came looking. In the meantime, it made it easier for supply runs to get through, even if no one seemed to know how we were getting those supplies, and it would make it eas

My story ended, but I remember everything. I remember the cold dread as I watched the lights on the blood test unit turn red, one by one, until my infection was confirmed. I remember the look on Shaun’s face when he realized this was it—it was really happening, and there wasn’t going to be any clever third act solution that got me out of the van alive.

I remember the barrel of the gun against my skin. It was cool, and it was soothing, because it meant Shaun would do what he had to do. No one else would get hurt because of me.

No one but Shaun.

This was something we’d never planned for. I always knew that one day he’d push his luck too far, and I’d lose him. We never dreamed that he would be the one losing me. I wanted to tell him it would be okay. I wanted to lie to him. I remember that: I wanted to lie to him. And I couldn’t. There wasn’t time, and even then, I didn’t have it in me.

I remember starting to write. I remember thinking this was it; this was my last chance to say anything I wanted to say to the world. This was the thing I was going to be judged on, now and forever. I remember feeling my mind start to go. I remember the fear.

I remember the sound of Shaun pulling the trigger.

I shouldn’t remember anything after that. That’s where my story ended. Curtain down, save file, that’s a wrap. Once the bullet hits your spinal cord, you’re done; you don’t have to worry about this shit anymore. You definitely shouldn’t wake up in a windowless, practically barren room that looks suspiciously like a CDC holding facility, with no one to talk to but some unidentified voice on the other side of a one-way mirror.

The bed where I’d woken up was bolted to the floor, and so was the matching bedside table. It wouldn’t do to have the mysteriously resurrected dead journalist throwing things at the mirror that took up most of one wall. Naturally, the wall with the mirror was the only wall with a door—a door that refused to open. I’d tried waving my hands in front of every place that might hold a motion sensor, and then I’d searched for a test panel in the vain hope that checking out clean would make the locks let go and release me.

There were no test panels, or screens, or ocular scanners. There wasn’t anything inside that seemed designed to let me out. That was chilling all by itself. I grew up in a post-Rising world, one where blood tests and the threat of infection are a part of daily life. I’m sure I’d been in sealed rooms without testing units before. I just couldn’t remember any.

The room lacked something else: clocks. There was nothing to let me know how much time had passed since I woke up, much less how much time had passed before I woke up. There’d been a voice from the speaker above the mirror, an unfamiliar voice asking my name and what the last thing I remembered was. I’d answered him—“My name is Georgia Mason. What the fuck is going on here?”—and he’d gone away without answering my question. That might have been ten minutes ago. It might have been ten hours ago. The lights overhead glared steady and white, not so much as flickering as the seconds went slipping past.

That was another thing. The overhead lights were industrial fluorescents, the sort that have been popular in medical facilities since long before the Rising. They should have been burning my eyes like acid… and they weren’t.

I was diagnosed with retinal Kellis-Amberlee when I was a kid, meaning that the same disease that causes the dead to rise had taken up permanent residence in my eyeballs. It didn’t turn me into a zombie—retinal KA is a reservoir condition, one where the live virus is somehow contained inside the body. Retinal KA gave me extreme light sensitivity, excellent night vision, and a tendency to get sickening migraines if I did anything without my sunglasses on.

Well, I wasn’t wearing sunglasses, and it wasn’t like I could dim the lights, but my eyes still didn’t hurt. All I felt was thirst, and a vague, gnawing hunger in the pit of my stomach, like lunch might be a good idea sometime soon. There was no headache. I honestly couldn’t decide whether or not that was a good sign.

Anxiety was making my palms sweat. I scrubbed them against the legs of my unfamiliar white cotton pajamas. Everything in the room was unfamiliar… even me. I’ve never been heavy—a life spent running after stories and away from zombies doesn’t encourage putting on weight—but the girl in the one-way mirror was thin to the point of being scrawny. She looked like she’d be easy to break. Her hair was as dark as mine. It was also too long, falling past her shoulders. I’ve never allowed my hair to get that long. Hair like that is a passive form of suicide when you do what I do for a living. And her eyes…

Her eyes were brown. That, more than anything else, made it impossible to think of her face as my own. I don’t have visible irises. I have pupils that fill all the space not occupied by sclera, giving me a black, almost emotionless stare. Those weren’t my eyes. But my eyes didn’t hurt. Which meant either those were my eyes, and my retinal KA had somehow been cured, or Buffy was right when she said the afterlife existed, and this was hell.

I shuddered, looking away from my reflection, and resumed what was currently my main activity: pacing back and forth and trying to think. Until I knew whether I was being watched, I had to think quietly, and that made it a hell of a lot harder. I’ve always thought better when I do it out loud, and this was the first time in my adult life that I’d been anywhere without at least one recorder running. I’m an accredited journalist. When I talk to myself, it’s not a sign of insanity; it’s just my way of making sure I don’t lose important material before I can write it down.

None of this was right. Even if there was some sort of experimental treatment to reverse amplification, someone would have been there to explain things to me. Shaun would have been there. And there it was, the reason I couldn’t believe any of this was right: I remembered him pulling the trigger. Even assuming it was a false memory, even assuming it never happened, why wasn’t he here? Shaun would move Heaven and Earth to reach me.

I briefly entertained the idea that he was somewhere in the building, forcing the voice from the intercom to tell him where I was. Regretfully, I dismissed it. Something would have exploded by now if that were true.

“Goddammit.” I scowled at the wall, turned, and started in the other direction. The hunger was getting worse, and it was accompanied by a new, more frustrating sensation. I needed to pee. If someone didn’t let me out soon, I was going to have a whole new set of problems to contend with.

“Run the timeline, George,” I said, taking some comfort in the sound of my voice. Everything else might have changed, but not that. “You were in Sacramento with Rick and Shaun, running for the van. Something hit you in the arm. One of those syringes like they used at the Ryman farm. The test came back positive. Rick left. And then… then…” I faltered, having trouble finding the words, even if there was no one else to hear them.

Everyone who grew up after the Rising knows what happens when you come into contact with the live form of Kellis-Amberlee. You become a zombie, one of the infected, and you do what every zombie exists to do. You bite. You infect. You kill. You feed. You don’t wake up in a white room, wearing white pajamas and wondering how your brother was able to shoot you in the neck without even leaving a scar.

Scars. I wheeled and stalked back to the mirror, pulling the lid on my right eye open wide. I learned how to look at my own eyes when I was eleven. That’s when I got my first pair of protective contacts. That’s also when I got my first visible retinal scarring, little patches of tissue scorched beyond recovery by the sun. We caught it in time to prevent major vision loss, and I got a lot more careful. The scarring created small blind spots at the center of my vision. Nothing major. Nothing that interfered with fieldwork. Just little spots.

My pupil contracted to almost nothing as the light hit it. The spots weren’t there. I could see clearly, without any gaps.

“Oh.” I lowered my hand. “I guess that makes sense.”

I paused, feeling suddenly stupid as that realization led to another. When I first woke up, the voice from the intercom told me all I had to do was speak, and someone would hear me. I looked up at the speaker. “A little help here?” I said. “I need to pee really bad.”

There was no response.

“Hello?”

There was still no response. I showed my middle finger to the mirror before turning and walking back to the bed. Once there, I sat and settled into a cross-legged position, closing my eyes. And then I started waiting. If anyone was watching me—and someone had to be watching me—this might be a big enough change in my behavior to get their attention. I wanted their attention. I wanted their attention really, really badly. Almost as badly as I wanted a personal recorder, an Internet connection, and a bathroom.

The need for a bathroom crept slowly higher on the list, accompanied by the need for a drink of water. I was beginning to consider the possibility that I might need to use a corner of the room as a lavatory when the intercom clicked on. A moment later, a new voice, male, like the first one, spoke: “Miss Mason? Are you awake?”

“Yes.” I opened my eyes. “Do I get a name to call you by?”

He ignored my question like it didn’t matter. Maybe it didn’t, to him. “I apologize for the silence. We’d expected a longer period of disorientation, and I had to be recalled from elsewhere in the building.”

“Sorry to disappoint you.”

“Oh, we weren’t disappointed,” said the voice. He had the faintest trace of a Midwestern accent. I couldn’t place the state. “I promise, we’re thrilled to see you up and coherent so quickly. It’s a wonderful indicator for your recovery.”

“A glass of water and a trip to the ladies’ room would do more to help my recovery than apologies and evasions.”

Now the voice sounded faintly abashed. “I’m sorry, Miss Mason. We didn’t think… just a moment.” The intercom clicked off, leaving me in silence once again. I stayed where I was, and kept waiting.

The sound of a hydraulic lock unsealing broke the quiet. I turned to see a small panel slide open above the door, revealing a red light. It turned green and the door slid smoothly open, revealing a skinny, nervous-looking man in a white lab coat, eyes wide behind his glasses. He was clutching his clipboard to his chest like he thought it afforded him some sort of protection.

“Miss Mason? If you’d like to come with me, I’d be happy to escort you to the restroom.”

“Thank you.” I unfolded my legs, ignoring pins and needles in my calves, and walked toward the doorway. The man didn’t quite cringe as I approached, but he definitely shied back, looking more uneasy with every step I took. Interesting.

“We apologize for making you wait,” he said. His words had the distinct cadence of something recited by rote, like telephone tech support asking for your ID and computer serial number. “There were a few things that had to be taken care of before we could proceed.”

“Let’s worry about that after I get to the bathroom, okay?” I sidestepped around him, out into the hall, and found myself looking at three hospital orderlies in blue scrubs, each of them pointing a pistol in my direction. I stopped where I was. “Okay, I can wait for my escort.”

“That’s for the best, Miss Mason,” said the nervous man, whose voice I now recognized from the intercom. It just took a moment without the filtering speakers between us. “Just a necessary precaution. I’m sure you understand.”

“Yeah. Sure.” I fell into step behind him. The orderlies followed us, their aim never wavering. I did my best not to make any sudden moves. Having just returned to the land of the living, I was in no mood to exit it again. “Am I ever going to get something I can call you?”

“Ah…” His mouth worked soundlessly for a moment before he said, “I’m Dr. Thomas. I’ve been one of your personal physicians since you arrived at this facility. I’m not surprised you don’t remember me. You’ve been sleeping for some time.”

“Is that what the kids are calling it these days?” The hall was built on the model I’ve come to expect from CDC facilities, with nothing breaking the sterile white walls but the occasional door and the associated one-way mirrors looking into patient holding rooms. All the rooms were empty.

“You’re walking well.”

“It’s a skill.”

“How’s your head? Any disorientation, blurred vision, confusion?”

“Yes.” He tensed. I ignored it, continuing. “I’m confused about what I’m doing here. I don’t know about you, but I get twitchy when I wake up in strange places with no idea how I got there. Will I be getting some answers soon?”

“Soon enough, Miss Mason.” He stopped in front of a door with no mirror next to it. That implied that it wasn’t a patient room. Better yet, there was a blood test unit to one side. I never thought I’d be so happy for the chance to be jabbed with a needle. “We’ll give you a few minutes. If you need anything—”

“Using the bathroom, also a skill.” I slapped my palm down on the test panel. Needles promptly bit into the heel of my hand and the tips of my fingers. The light over the door flashed between red and green before settling on the latter. Uninfected. The door swung open. I stepped through, only to stop and scowl at the one-way mirror taking up most of the opposite wall. The door swung shut behind me.

“Cute,” I muttered. The need to pee was getting bad enough that I didn’t protest the situation. I glared at the mirror the entire time I was using the facilities, all but daring someone to watch me. See? I can pee whether you’re spying on me or not, you sick bastards.

Other than the mirror—or maybe because of the mirror—the bathroom was as standard-issue CDC as the hallway outside, with white walls, a white tile floor, and white porcelain fixtures. Everything was automatic, including the soap dispenser, and there were no towels; instead, I dried my hands by sticking them into a jet of hot air. It was one big exercise in minimizing contact with any surface. When I turned back to the door, the only things I’d touched were the toilet seat and the floor, and I was willing to bet that they were in the process of self-sterilization by the time I started washing my hands.

The blood test required to exit the bathroom was set into the door itself, just above the knob. It didn’t unlock until I checked out clean.

The three orderlies were waiting in the hall, with an unhappy Dr. Thomas between them and me. If I did anything bad enough to make them pull those triggers, the odds were good that he’d be treated as collateral damage.

“Wow,” I said. “Who did you piss off to get this gig?”

He flinched, looking at me guiltily. “I’m sure I don’t know what you mean.”

“Of course not. Thank you for bringing me to the bathroom. Now, could I get that water?” Better yet, a can of Coke. The thought of its acid sweetness was enough to make my mouth water. It’s good to know that some things never change.

“If you’d come this way?”

I gave the orderlies a pointed look. “I don’t think I have much of a choice, do you?”

“No, I suppose you don’t,” he said. “As I said, a precaution. You understand.”

“Not really, no. I’m unarmed. I’ve just passed two blood tests. I don’t understand why I need three men with guns covering my every move.” The CDC has been paranoid for years, but this was taking it to a new extreme.

Dr. Thomas’s reply didn’t help: “Security.”

“Why do people always say that when they don’t feel like giving a straight answer?” I shook my head. “I’m not going to make trouble. Please, just take me to the water.”

“Right this way,” he said, and started back the way we’d come.

There was a tray waiting for us on the bolted-down table in the room where I’d woken up. It held a plate with two pieces of buttered toast, a tumbler full of water, and wonder of wonders, miracle of miracles, a can of Coke with condensation beading on the sides. I made for the tray without pausing to consider how the orderlies might react to my moving faster than a stroll. None of them shot me in the back. That was something.

The first bite of toast was the best thing I’d ever tasted, at least until I took the second bite, and then the third. Finally, I crammed most of the slice into my mouth, barely chewing. I managed to resist the siren song of the Coke long enough to drink half the water. It tasted as good as the toast. I put down the glass, popped the tab on the can of soda, and took my first post-death sip of Coke. I was smart enough not to gulp it; even that tiny amount was enough to make my knees weak. That, and the caffeine rush that followed, provided the last missing piece.

Slowly, I turned to face Dr. Thomas. He was standing in the doorway, making notes on his clipboard. There were probably a few dozen video and audio recorders running, catching every move I made, but any good reporter will tell you that there’s nothing like real field experience. I guess the same thing applies to scientists. He lowered his pen when he saw me looking.

“How do you feel?” he asked. “Dizzy? Are you full? Did you want something besides toast? It’s a bit early for anything complicated, but I might be able to arrange for some soup, if you’d prefer that…”

“Mostly, what’d I’d prefer is having some questions answered.” I shifted the Coke from one hand to the other. If I couldn’t have my sunglasses, I guess a can of soda would have to do. “I think I’ve been pretty cooperative up to now. I also think that could change.”

Dr. Thomas looked uncomfortable. “Well, I suppose that will depend on what sort of questions you want to ask.”

“This one should be pretty easy. I mean, it’s definitely within your skill set.”

“All right. I can’t promise to know the answer, but I’m happy to try. We want you to be comfortable.”

“Good.” I looked at him levelly, missing my black-eyed gaze. It always made people so uncomfortable. I got more honest answers out of those eyes… “You said you were my personal physician.”

“That’s correct.”

“So tell me: How long have I been a clone?”

Dr. Thomas dropped his pen.

Still watching him, I raised my Coke, took a sip, and waited for his reply.

Subject 139b was bitten on the evening of June 24, 2041. The exact time of the bite was not recorded, but a period of no less than twenty minutes elapsed between exposure and initial testing. The infected individual responsible for delivering the bite was retrieved from the road. Posthumous analysis confirmed that the individual was heavily contagious, and had been so for at least six days, as the virus had amplified through all parts of the body.

Blood samples were taken from the outside of Subject 139b’s hand and sequenced to prove that they belonged to the subject. Analysis of these samples confirmed the infection. (For proof of live viral bodies in Subject 139b’s blood, see the attached file.) Amplification appears to have begun normally, and followed the established progression toward full loss of cognitive functionality. Samples taken from Subject 139b’s clothing confirm this diagnosis.

Subject 139b was given a blood test shortly after arriving at this facility, and tested clean of all live viral particles. Subject 139b was given a second test, using a more sensitive unit, and once again tested clean. After forty-eight hours of isolation, following standard Kellis-Amberlee quarantine procedures, it is my professional opinion that the subject is not now infected, and does not represent a danger to himself or others.

With God as my witness, Joey, I swear to you that Shaun Mason is not infected with the live state of Kellis-Amberlee. He should be. He’s not. He started to amplify, and he somehow fought the infection off. This could change everything… if we had the slightest fucking clue how he did it.

—Taken from an e-mail sent by Dr. Shannon Abbey to Dr. Joseph Shoji at the Kauai Institute of Virology, June 27, 2041.

Times like this make me think my mother was right when she told me I should aspire to be a trophy wife. At least that would have reduced the odds of my winding up hiding in a renegade virology lab, hunting zombies for a certifiable mad scientist.

Then again, maybe not.

—From Charming Not Sincere, the blog of Rebecca Atherton, July 16, 2041. Unpublished.

Shaun! Look out!”

Alaric’s shout came through my headset half a second before a hand grabbed my elbow, bearing down with that weird mixture of strength and clumsiness characteristic of the fully amplified. I yanked free, whirling to smack my assailant upside the head with my high-powered cattle prod.

A look of almost comic surprise crossed the zombie’s face as the electrified end of the cattle prod hit its temple. Then it fell. I kicked the body. It didn’t move. I hit it in the solar plexus with my cattle prod, just to be sure. Electricity has always been useful against zombies, since it confuses the virus that motivates them, but it turns out that when you amp the juice enough you can actually shut them down for short periods of time.

“Thanks for the heads-up,” I said, trusting the headset to pick me up. “I’ve got another dead boy down. Send the retrieval team to my coordinates.” I was already starting to scan the trees, looking for signs of movement—looking for something else that I could hit.

“Shaun…” There was a wary note in Alaric’s voice. I could practically see him sitting at his console, knotting his hands in his hair and trying not to let his irritation come through the microphone. I was his boss, after all, which meant he had to at least pretend to be respectful. Once in a while. “That’s your fourth catch of the night. I think that’s enough, don’t you?”

“I’m going for the record.”

There was a click as Becks plugged her own channel into the connection and snapped peevishly, “You’ve already got the record. Four catches in a night is twice what anyone else has managed, ever. Now please, please, come back to the lab.”

“What will you do if I don’t?” I asked. Nothing seemed to be moving, except for my infected friend, who twitched. I zapped him with the cattle prod again. The movement stopped.

“Two words, Shaun: tranquilizer darts. Now come back to the lab.”

I whistled. “That’s not playing fair. How about you promise to bake me chocolate chip cookies if I come back? That seems like a much better incentive.”

“How about you stop screwing around before you make me angry? Immune doesn’t mean immortal, you know. Now please.” The peevishness faded, replaced by pleading. “Just come home.”

She’s right, said George—or the ghost of George, anyway, the little voice at the back of my head that’s all I have left of my adopted sister. Some people say I have issues. I say those people need to expand their horizons, because I don’t have issues, I have the Library of Congress. You need to go back. This isn’t doing anybody any good.

“I don’t know,” I said. I used to be circumspect about talking to George. That was before I decided to go all the way insane. Madness is surprisingly freeing. “I mean, I’m having fun. Aren’t you the one who used to nag me to get my butt back into the field? Is this field enough for you?”

Shaun. Please.

My smile faded. “Fine. Whatever. If you want me to go back to the stupid lab, I’ll go back to the stupid lab. Happy now?”

No, said George. But it’s going to have to do.

I poked my latest catch one last time with the cattle prod. It didn’t react. I turned to stalk back through the trees to the ripped-up side road where the bike was parked. Gunshots sounded from the forest to my left. I paused. Silence followed them, rather than screaming. I nodded and started walking again. Maybe that seems callous, but I wasn’t the only one collecting virtual corpses for Dr. Abbey, the crazy renegade virologist who’d been sheltering us since we were forced off the grid. Most of her lab technicians were either ex-military or trained marksmen. They could take care of themselves, at least in the “killing stuff” department. I was less sure about bringing the zombies home alive. Fortunately for me, that was their problem, not mine.

Alaric’s sigh of relief made me jump. I’d almost forgotten that he and Becks were listening in from their cozy spot in the main lab. “Thank you for seeing sense.”

“Don’t thank me,” I said. “Thank George.”

Neither of them had anything to say to that. I hadn’t expected them to. I tapped the button on the side of my headset, killing the connection, and kept walking.

It had been just under a month since the world turned upside down. Some days, I was almost grateful to be waking up in an underground virology lab. Sure, most of the things it contained could kill me—including the head virologist, who I suspected of having fantasies about dissecting me so she could analyze my organs—but at least we knew what was going on. We had a place, if not a fully functional plan. That put us way ahead of the surviving denizens of North America’s Gulf Coast, who were still contending with something we’d never anticipated: an insect vector for Kellis-Amberlee.

A tropical storm had blown some brand-new strain of mosquito over from Cuba, one with a big enough bite to transmit the live virus to humans. No one had heard of an insect vector for Kellis-Amberlee before that day. The entire world had heard of it on the day after, as every place Tropical Storm Fiona touched discovered the true meaning of “storm damage.” The virus spread initially with the storm, and then started spreading on its own as the winds died down and the mosquitoes went looking for something to munch on. It was a genuine apocalypse scenario, the sort of thing that makes trained medical personnel shit their pants and call for their mommies. And it was really happening, and there wasn’t a damn thing we could do about it.

The worst part? Even if no one wanted to say it out loud, when you looked at the timing of everything going wrong—the way it all happened just as we started really prodding at the CDC’s sore spots—I thought there was a pretty good chance it wasn’t an accident. And that would mean it was our fault.

There was no one standing watch over the vehicles. That was sloppy; even if we cleared out the human infected, there was always the chance a zombie raccoon or something could take refuge under one of the collection vans and go for somebody’s ankles when they came back with the evening’s haul. I made a mental note to talk to Dr. Abbey about her tactical setup as I swung a leg over the bike. Then I put on my helmet—Becks was right, immune doesn’t mean immortal—and took off down the road.

See, here’s the thing. My name is Shaun Mason; I’m a journalist, I guess, even though right now all my posts are staying unpublished for security’s sake. I’m not technically wanted for anything. It’s just that places where I show up have a nasty tendency to get wiped off the map shortly after I get there, and that makes me a little gun-shy when it comes to telling people where I am. I think that’s understandable. Then again, I also think my dead sister talks to me, so what do I know?

About a year and a half ago—which feels like yesterday and an eternity at the same time—George and I applied to blog for Senator Peter Ryman’s presidential campaign, along with our friend Georgette “Buffy” Meissonier. Before that, I was your average gentleman Irwin, wanting nothing beyond a few dead things to poke with sticks and the opportunity to write up my adventures for an adoring populace. Pretty simple, right? The three of us had everything we needed to be happy. Only we didn’t know that, so when the chance to grab for glory came, we took it. We wanted to make history.

We made it, all right. We made it, Buffy and George became it, and I wound up as the last man standing, the one who has to avenge the glorious dead. All I know is that part wasn’t in the brochure.

The road smoothed as I got closer to our current home-sweet-home. Shady Cove, Oregon, has been deserted since the Rising, when the infected left the tiny community officially uninhabitable. We had to be careful about how visible we were, but Dr. Abbey had been sending her interns—interning for what, I didn’t know, since most universities don’t offer a degree in mad science—out at night to patch the worst of the potholes with a homebrewed asphalt substitute that looked just like the real thing.

Fixing the road was a mixed blessing. It could give away our location if someone came looking. In the meantime, it made it easier for supply runs to get through, even if no one seemed to know how we were getting those supplies, and it would make it eas

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved