- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

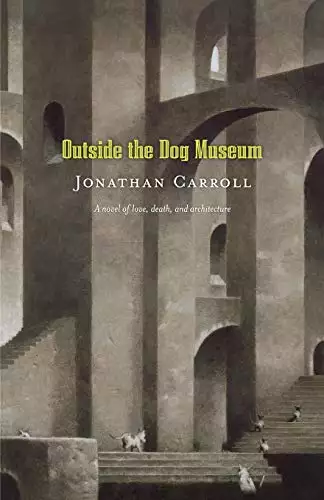

Synopsis

Harry Radcliffe is a brilliant prize-winning architect---witty and remarkable. He's also a self-serving opportunist, ready to take advantage of whatever situations, and women, come his way. But now, newly divorced and having had an inexplicable nervous breakdown, Harry is being wooed by the extremely wealthy Sultan of Saru to design a billion-dollar dog museum. In Saru, he finds himself in a world even madder and more unreal than the one he left behind, and as his obsession grows, the powers of magic weave around him, and the implications of his strange undertaking grow more ominous and astounding....

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: June 1, 2005

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Outside the Dog Museum

Jonathan Carroll

part one

"present tense"

I would rather shape my soul than furnish it.

--MONTAIGNE

I'D JUST BITTEN THE hand that fed me when God called, again. Shaking her left hand, Claire picked up the receiver with her right. After asking who it was, she held it out to me, rolling her eyes. "It's God again." Her little joke. The Sultan's name was Mohammed, and he was more or less God to the million and a half citizens of the Republic of Saru, somewhere in the Persian Gulf.

"Hello, Harry?"

"Hello, sir. The answer is still no."

"Have you seen the Mercedes-Benz building on Sunset Boulevard? This is a building I like very much."

"Sure, Joe Fontanilla designed it. He's with the Nadel Partnership. Call him up."

"He was not in Time magazine."

"Your Highness, the only reason you want me to work for you is because I was on the cover of that magazine. I don't think that's the best reason for choosing someone to do a billion-dollar project."

"'It was announced last week that American Harry Radcliffe was awarded this year's Pritzker Prize, architecture's equivalent of the Nobel Prize.'"

"You're reading from the article again."

"I also liked the coffeepot you designed. Come over to my hotel, Harry, and I'll give you a car."

"You already gave me a car last week, sir. I can only drive one at a time. Anyway, the answer would still be no. I don't design museums."

"Your friend Fanny Neville is here."

My other friend, Claire Stansfield, stood with her long, naked back to me, looking out her glass doors down onto Los Angeles, way below.

Claire here, Fanny at the Sultan's. The salt and pepper on my life those days.

"How did that happen?" I tried to keep the word "that" noncommittal so Claire wouldn't get suspicious.

"I asked your friend Fanny if she would like to do an interview with me."

Fanny Neville likes two things: power and imagination. She prefers both, but will take one if the other's unavailable. I was the imagination in her life those days. We'd met in New York a couple of years before when she interviewed me for Art in America. I give good interviews, or did before I went off my rocker and had to drop out of life for a while.

I was back in it now, but wasn't doing much besides commuting between these two impressive women, who both said it was time I got off my ass and did something.

"Could I talk to him?"

"Him? You mean Fanny? With pleasure."

There was a pause and then she came on the line. "Hello. Are you at Claire's?"

"Yes."

"That always makes me feel cozy. Do you talk to her in this same voice when you call from my house?"

"Yes."

"You're an asshole, Harry. How come you didn't tell me the Sultan wants you to build his museum?"

"Because I already said I wouldn't."

"But you took the car he gave you?"

"Sure, why not? It was a gift."

"A forty-thousand-dollar gift?"

"He just offered me another."

"I heard." She "hmph'd" like a disgruntled old woman. "Are you coming to my house for dinner?"

"Yes."

Claire turned around, the sunshine from behind lighting her outline so brightly that I could barely make out her nakedness. Walking toward me, she did something with her foot, and the telephone line went dead. It took a moment to realize she'd pulled out the cord.

"Talk to her on your own fucking time, Harry."

BEFORE GOING OVER TO visit Fanny and the Sultan, I drove to my favorite car wash in West Hollywood. It's run by a bunch of fags who do everything beautifully and with style.

I've done some of my best thinking in car washes. Those few minutes under the mad flood and yellow brushes do things to some outlying but valuable part of my brain so that I usually emerge from those false storms wired and full of ideas. Are you familiar with the Andromeda Center in Birmingham, England? The one that brought me so much notoriety a decade ago? Born in a car wash. I remember "fixing" on the swishing arc of the windshield wiper blades on my car and, just before the hoses stopped, having the first inspiration for those juxtaposed arcs that are the heart of that justly famous building.

Sitting in the Hollywood car wash, watching my new Lotus get spritzed from all sides, I was a famous man with nothing to do. I was twice divorced; once even from an anorectic fashion victim whose sole creative act in life was to spell her name with two d's. Anddrea. She liked to fuck in the morning and complain the rest of the day. We were married too long and then she left me for a much nicer man.

I am not a nice man. I expect others to be nice to me, but feel nocompulsion to return the favor. Luckily enough, important people have called me a genius throughout my adult life so that I've been able to get away with an inordinate amount of rudeness, indifference, and plain bad manners. If you're ever given one wish, wish the world thinks you're a genius. Geniuses are allowed to do anything. Picasso was a big prick, Beethoven never emptied his chamber pot, and Frank Lloyd Wright stole as much money from his clients and sponsors as any good thief. But it was all okay finally because they were "geniuses." Maybe they were, and I am too, but I'll tell you something: Genius is a boat that sails itself. All you have to do is get in and it does the rest, i.e., I didn't spend months and years thinking up the shapes and forms of my most renowned buildings. They came out of nowhere and my only job was to funnel them onto pieces of paper. I'm not being modest. The ideas come like breezes through a window and all you do is capture them. Braque said this: "One's style--it is in a way one's inability to do otherwise ... . Your physical constitution practically determines the shape of the brushmarks." He was right. Bullshit on all that artistic suffering, "agonizing" over the empty page, canvas ... . Anyone who agonizes over their work isn't a genius. Anyone who agonizes for a living is an idiot.

Halfway through the second rinse (my favorite part came next--the dry off, when curtains of brown rags descended and slid sensuously across every surface of the car), everything stopped. My beautiful new blue Lotus (compliments of the Sultan) sat there dripping water, going nowhere. Checking the rearview mirror, I saw the car behind me was stopped too. The driver and I made eye contact. He shrugged.

Trapped in a gay car wash!

A few moments twiddling my fingers on the steering wheel, then I watched a couple of workers run by close on the right and out the other end. Another glance in the rearview mirror, the guy behind shrugging again. I got out of the car and, looking toward the exit,saw some kind of large commotion going on up there. I walked toward it.

"What kinda car is dat?"

"Fuck the car, Leslie, the guy's dead!"

A brown car (I remember thinking it was the same color as the drying rags) sat a few feet from the exit. Four or five people stood around, looking inside. The driver's door was open and the manager of the place was hunched down next to it. He looked at me and asked if I was a doctor--the guy inside had had a heart attack or something, and was dead. Immediately I said yes because I wanted to see. Going over, I knelt down next to the manager.

Despite having just been cleaned, the car still smelled of loaded ashtrays and wet old things. A middle-aged man sat slumped over the steering wheel. Remembering my television shows, I made like a doctor and put a hand on his throat to feel for a pulse. Nothing there under jowls and whiskery skin. "He's gone. Did you call an ambulance?"

The manager nodded and we stood up together.

"How do you think it happened, Doctor?"

"Heart attack, probably. But best to let the ambulance men figure it out."

"What a way to go, huh? Okay, Leslie and Kareem, give me a hand pushing this car out of here so we can let the rest of these people through. Thanks, Doctor. Sorry to inconvenience you."

"No problem." I turned to go back to my car.

"How embarrassing."

"Excuse me?" I looked at him.

"I mean I run this place and all, right? But I was thinking how humiliating it'd be to know that you'd die in a car wash--especially if you were famous! Imagine how your obituary would read: 'Graham Gibson, renowned actor, was found dead in The Eiffel Towel Car Wash, Thursday, after having apparently suffered a massive heart attack.'" He looked at me and grimaced. "Washed to death!"

"I know what you mean."

An enormous understatement. Some people fantasize their names on magazine covers, others on bronze plaques mounted on the sides of buildings. I did too, until some of those things happened to me. Then I started imagining what my obituary would say. I once read that the man who did the obituaries for the New York Times wrote them before people died (if they were well-known) and only polished them with final details after the person croaked. That was understandable and I could see the logic to it, but the "polish" part was disturbing. Okay, you live a long and illustrious life, full of genuine accomplishments and praise. But then what happens? You finish, looking like a big dope if you're unfortunate enough to die choking on a bottle cap, or a tree branch hits you on the head and puts you down for the count. Tennessee Williams with the bottle cap, Odon Von Horvath with the tree. I know nothing about Odon except he was a writer and that's how he died--hit on the head by a branch while walking down a street in Paris. I could too easily imagine someone saying, "I know nothing about Harry Radcliffe except he was an architect who died of a heart attack in a car wash." The Eiffel Towel Car Wash, no less.

Walking back to the car, I reminded myself of the fact that I hadn't been doing anything with my days recently, so if it had been me keeled over in that brown car, my whole life would have looked pretty pointless.

"What happened up there?" The man in the car behind mine was out and standing now.

"A guy had a heart attack and died."

"Here?" He shook his head and smiled. I knew what he was thinking and it made me even more depressed: It was funny. People would grin if you said you were at the car wash today and someone died while on his final rinse. They'd smile the same way as this man, and thenthere'd be one of those half-funny, half-fearful discussions at the dinner table about good and bad ways of dying.

Venasque used to say down deep we all know we're kind of silly and thus spend too much of our lives either trying to cover it up or disprove it--mostly to ourselves. "But then when it comes to dying," he would say, "you know you might end up looking more ridiculous than ever. Even though you're dead and won't be around to see people's reactions, you're still afraid to look bad. Why do you think people like expensive coffins and funerals so much? So we can try being impressive, right into the ground."

FIVE MINUTES LATER, PULLING up at a stoplight on Sunset Boulevard, I looked to my left, and who was sitting in the car next to mine? Markus Hebenstreit! Architecture critic for the L.A. Eye, Hebenstreit was my most vicious and long-standing enemy/critic. He'd probably written more bad things about my work than anyone else. The more famous I became, the more Hebenstreit frothed and spread his verbal rabies wherever he could.

"Markus!"

He turned slowly and looked at me with great Hoch Deutsch disdain. When I registered on him, his contempt turned into beady-eyed hatred. "Hello, Radcliffe. Coming back from your weekly shock treatment?"

"A new billion-dollar project, Markus! Man wants me to build him a billion-dollar museum. Do it however I want, just so long as it's an original Harry Radcliffe.

"Just think, Markus, no matter what you write, there'll always be someone who wants me to build them billion-dollar buildings!

"So suck on that a while, you Nazi fuck!"

Before he could say anything, I slapped the Lotus into gear and peeled out, feeling gloriously like an eighteen-year-old.

RUMOR HAD IT THE Sultan of Saru owned the Westwood Muse Hotel, which explained why he and his entourage invariably stayed there when they came to Los Angeles five or six times a year. It was designed and built in the 1930s by a student of Peter Behrens and looked sort of like the jazzy factories Behrens designed for AEG in Germany. I liked the place because it was quirky, but couldn't understand why the Sultan would buy it when he could have so easily afforded any real estate within a ten-mile radius of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

When I pulled up in front, an extremely tall black woman dressed in a dove-gray shirt and slacks stepped forward and opened my door. As usual, I looked up at her in pure appreciation. She was exquisite.

"Hello, Lucia."

"Hello, Harry. Has he invited you again?"

"Summoned."

She nodded and took my place in the car. The two complemented each other perfectly; the machine should have been hers on the basis of looks and stature alone. But it wasn't. Lucia was only another beautiful failure in California, parking cars.

"He still wants you to build his museum?"

"Yup."

"And you don't want to do it?" Her long brown hands sat lightly on the steering wheel. She smiled up at me and that smile was a killer.

I thought about answering her, but asked instead, "What do you want to be when you grow up?"

Not sure whether I was being serious or not, she cocked her head to one side and said, "'When I grow up'? An actress. Why?"

"You'd like that carved on your tombstone? 'Lucia Armstrong, actress'?"

"That would make me very happy. What about you, Harry? What do you want written, 'Harry Radcliffe, celebrated architect'?"

"Naah, that's too banal. Maybe 'The Man Who Built the Dog Museum.'" Said like that, the idea suddenly tickled the hell out of me. Walking up the gravel path, I turned to say something else to Lucia but she was already pulling away. I shouted to the back of my blue car, "That'd be a damned good epitaph!"

Was it because of the dead man in the car wash? Being able to throw the power of "a billion dollars" in Hebenstreit's face? Or simply envisioning (and liking) the words "The Man Who Built the Dog Museum" on my gravestone that did it? Whatever the reason, walking in the front door of the Westwood Muse Hotel, I knew I would design the Sultan's museum for him, although I had been saying no for months.

What I had to do next was get him to think he was not just lucky, but blessed to have me and, consequently, fork over the money I'd need both for myself and the project. A lot more money than even he'd imagined.

WHAT ARE YOUR EARLIEST memories?"

Was the first question Fanny Neville asked me, the day we met and did our interview years before. I hadn't even had the chance to sit back down after letting her in.

Without thinking, I said, "Seeing Sputnik and Rocket Monroe at the Luxor Baths in New York."

"How old were you?"

"Three, I think."

"Who were Sputnik and Rocket Monroe?"

"Professional wrestlers."

MY FATHER, DESALLES "SONNY" Radcliffe, came from Basile, Louisiana. He knew how to catch snapping turtles, charm women, and make money. He often said the three things had a lot in common and that was why he was so successful.

With his curveball Southern accent, he'd say, "The say-crit to catching a snapping turtle, Harry, is to stick your foot down into that soft mud and feel around really gently.

"Now, once in a while one of them monsters is in there and'll grab hold of that foot. Hold still den! This is where the patience comes in. He's thinking what to do with it. That turtle can't decide 'cause he's mud-dumb. So you just take a deep breath and wait. I know you're dying to pull it out and run like a motherfuck, but don't. Hold still, boy, and you'll be all right. Women and money're the same: They clamp on ya and want to pull you down, but just wait 'em out and those jaws'll loosen up."

Pop liked someone watching TV with him at night. That was usually me from the very earliest because my mother had no patience for the tube.

He liked wrestling because he said it relaxed him. Channel Five from Uline Arena or Commack on Long Island.

I REMEMBER SITTING ON my father's lap and he'd say, 'That's Sweet Daddy Siki, Harry.'Or Bobo Brazil, Johnny Valentine, Fuzzy Cupid. Because I was young, and those names sounded so fairy taleish, I remembered them. Sputnik and Rocket Monroe were two bad guys with long black hair and white streaks painted down the middle of their manes so they both looked like skunks."

Fanny sat forward and pointed her eyeglasses at me. "That's where you got the names for your collection?"

"Exactly."

"You named furniture after professional wrestlers?"

"Yes, but then Philippe Starck stole the idea and named his stuff after characters from some science fiction novel.

"Look, everyone takes design too seriously. I thought by giving my work names, ridiculous names, it'd put things in perspective. A personwho pays five thousand dollars for a chair doesn't have much perspective."

She slid the glasses back on for the fourth time. Her face was oval and thin with large dark lips that sat in a fixed rosebud pout. The square black Clark Kent glasses made her look like she was trying too hard to appear serious.

"Then why do you charge five thousand dollars for a chair that you call 'Bobo Brazil,' Mr. Radcliffe?"

"Do your homework, Ms. Neville. I don't charge anything for the furniture I design--the company does. And they aren't charging for the chair or lamp, they're charging for my name. Anyway, I come cheap--Knoll charges ten grand for a Richard Meier chair."

"Don't you feel immoral being involved in that when you know so many people are suffering in the world?"

"Don't you feel immoral writing for a magazine that's only bought by pseudo-intellectuals and rich people who don't give a shit about the poor?"

"Touché. What were you doing at the Luxor Baths?"

"I was with my father, who was a Turkish bath nut. He believed you could do anything you wanted--drink a bottle of brandy or carouse all night, so long as you went to a Turkish bath the next day and sweated out your transgressions."

"Transgressions?" She smiled for the first time.

"I believe in words of more than one syllable."

"You like language?"

"I believe in it. It's the only glue that holds us together."

"What about your occupation? Doesn't the human community depend on its physical structures?"

"Yes, but it can't build them unless it can explain what kind it wants. Even when you're only making grass huts."

"What do you think of your work, Mr. Radcliffe?"

Without missing a beat or feeling the least bit guilty, I stole from Jean Cocteau once again. This time replacing only one word--"architect" for "writer." "'I believe that each of my works is capable of making the reputation of a single architect.'"

"You don't believe in modesty."

It was my turn to sit forward. "Who do you think is better than me?"

"Aldo Rossi."

I waved him away. "He makes cemeteries."

"Coop Himmelblau?"

"They design airplanes, not buildings."

"Honestly, don't you think anyone is better than you?"

I thought for a moment. "No."

"Do you mind if I quote you?"

As obnoxiously as possible, I slid into my father's Basile, Louisiana, drawl. "Aww now, Fenny, do you really think that's going to hurt me? Every interview I give, they quote that. Know what happens? I get more commissions! People like hiring a man who's sure of himself. Most particularly when you're responsible for a few hundred million dollars!"

Which was true. While talking to Fanny Neville that first time years ago, I was also thinking about the three projects on my desk: the Aachen, Germany, airport, the Rutgers University Arts Center in New Jersey, and the house I was building in Santa Barbara for Bronze Sydney and me.

Footnote: Bronze Sydney was my second wife. Bronwyn Sydney Davis. Bronze Sydney. We started out as partners, then married, but quickly realized we functioned better together as professional colleagues. A calm divorce followed. We are still partners and friends.

Both the Aachen and Rutgers projects came about because I'd assured specific people I was the best. That self-confidence, along with my plans and proposals, convinced them. I don't think the designsalone would have done it, although they were very significant and appropriate.

Ask anyone about the high point of their life. Odds are, whatever they say, it'll have something to do with being busy. I felt comfortable answering Fanny's question so bluntly because at that time I was a hurricane named H. Radcliffe, Important American Architect. I did feel like one of those tropical storms that builds in the Gulf of Mexico and scares everyone when the weather man says ominously, "Hurricane Harry is still biding its time out there, just growing bigger. But batten down those hatches, folks. This one is going to be a doozy!" I was a doozy, and getting bigger all the time because of the buildings we were putting up. There was fame, money by the pound, jobs designing anything I wanted. Bronze Sydney and I were working too hard, but loving the full-tilt feel of our lives. When we went to bed at night, we were still so wired that we'd often fuck for hours just to ground some of the electricity, angst, excitement, anticipation ... that'd built up in both of us over the day.

Then the storm hit, all right, but me, not the mainland.

MONTHS LATER, AFTER I'D won the Pritzker Prize (the second-youngest recipient in its history, let me add), the real honor came when I was invited to participate in the seven hundred fiftieth anniversary of the City of Berlin. As part of the celebration, the city fathers had intelligently decided to ask prominent architects from around the world to design new buildings with which to give that fearful, nervous city a face-lift.

A late twentieth-century city perched like a crucial and formidable lighthouse on the edge of communism. I thought it was as noble and utopian as we were ever going to get.

They asked me to design a section of the Berlin Technical University. Within an hour of the request, I knew what to do: What couldbe more appropriate for a technical university than a robot, seven stories high? I kept a collection of toy robots on my desk, and friends knew if they ever saw an interesting one to pick it up for me.

After spending the better part of two days with the door closed, all calls held, and the desk lamp tipped to illuminate the various figures, I began sketching a building that looked like a mixture of Russian constructivist collage, the sexy robot girl in Fritz Lang's Metropolis, and a "Masters of the Universe" doll. It was brainy, but not exceptional. I needed more stimulus.

There's a store in Los Angeles on Melrose Avenue that sells nothing but rubber spiders, Japanese robots, horror movie masks ... . Your typically overpriced, chic kitsch paradise where the pile of rubber dog shit you bought as a kid for forty-nine cents now costs seven dollars. Truth be told, I'd spent much time and money at that place when searching around for ideas for a new building. A thirty- or forty-dollar bagful of glow-in-the-dark werewolf fangs, little green-rubber-car pencil erasers, get-the-ball-in-the-hole puzzles ... spread out together in front of me usually helped, for some unique reason. Mallarmé got his inspiration from looking at the ocean. Harry Radcliffe got his from a fake fly in a fake ice cube.

The owners of the store gave me the heartiest of hellos whenever I came in. I think they were nice people, but I'd spent so much money there in the past that I could never tell if they were really nice or only money-nice. Money-nice lasts as long as you're a good customer.

"What's new?"

"We just got something I think you'll like very much." The man went to the back of the store and waved me over to him. I walked back as he was reaching down into a box on the floor.

"Look at these." He held out two handfuls of vividly colored little buildings, each about four or five inches long. I picked one up and gave a tickled yelp. "It's the Sphinx!"

"Right. And here's the Empire State Building, Sydney OperaHouse, Buckingham Palace ... all the famous buildings of the world as pencil sharpeners! Aren't they great? We just got them this week from Taiwan. Don't they look like pieces of bubble gum?"

I reached into the full box and rooted around for samples of each. A cobalt blue Leaning Tower of Pisa, vermilion Statue of Liberty (was that a building?), green Roman Colosseum. There were a surprising number of different ones. Taking a few to the front of the store where there was more light, I held them up and looked carefully at the detail. Superb.

I bought two hundred and fifty.

There was no screech of tires, screams, or thunderous crash when my mind went flying over the cliff into madness, as I gather is true in many cases. Besides, we've all seen too many bad movies where characters scratch their faces or make hyena sounds to indicate they've gone nuts.

Not me. One minute I was famous, successful, self-assured Harry Radcliffe in the trick store, looking for inspiration in a favorite spot. The next, I was quietly but very seriously mad, walking out of that shop with two hundred and fifty yellow pencil sharpeners. I don't know how other people go insane, but my way was at least novel.

Melrose Avenue is not a good place to lose your mind. The stores on the street are full of lunatic desires and are only too happy to let you have them if you can pay. I could.

Anyone want a gray African parrot named Noodle Koofty? I named him on the ride back to Santa Barbara. He sat silently in a giant black cage in the back of my Mercedes station wagon, surrounded by objects I can only cringe at when I think of them now: three colorful garden dwarves about three feet high, each holding a gold hitching ring; five Conway Twitty albums that cost twenty dollars each because they were "classics"; three identical Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs albums, "classics" as well, twenty-five dollars apiece; a box of bathroom tiles with a revolting peach motif; a wall-size poster of a chacmababoon in the same pose as Rodin's The Thinker ... other things too, but you get the drift.

My car was so loaded down in back that one might have thought I was transporting bags of cement. But all I was carrying was the alarming evidence of my dementia.

Why did it happen? How did I end up driving a station wagon full of plastic garden dwarves and Conway Twitty albums when I was at the height of my success? Believe me, I've thought about it since I recovered, and that's a long time. The standard explanations could be used to good effect--I was overworked, there was too much pressure to succeed, my marriage with Sydney was beginning to hiss and spit ominously at its seams ... .

Or none of the above.

After Venasque introduced me to the journals of Cocteau, I came across a passage which touched me deeply.

"Then I realized that my dream life was as full of memories as my real life, that it was a real life, denser, richer in episodes and in details of all kinds, more precise, in fact, and that it was difficult for me to locate my memories in one world or the other, that they were superimposed, combined, and creating a double life for me, twice as huge and twice as long as my own."

When I showed that to Venasque, he patted my shoulder.

"Exactly. That should answer your questions, Harry. You needed to go nuts! Most people do it either to hide, or because they can't cope. But you did it because no matter how much you thought you were doing things right, you weren't. And something inside knew it.

"Look at it this way: Your dream side decided you and it needed a vacation from your awake side, so it bought the tickets and packed bags for both of you. And off you guys went, leaving your awake side at home."

It was nice of the old man to call them my "dream" and "awake" sides when we both knew he meant Crazy Harry/Sane Harry. Yetwhat he said makes more and more sense the further removed I am from that turbulent time of my life. Some people do need to go crazy. To live fully in your "dream life" a while is like putting all the weight on your left foot when your right is exhausted. I wasn't crazy very long, but in certain specific ways those months adrift in "Lu-Lu Land" gave me two of the most important things in my life: a fuller, more balanced vision, and the indispensable Venasque.

I'm moving too fast. Rerun the tape to where Noodle Koofty and I and our inanimate friends in the back of my Mercedes station wagon are tooling up the Pacific Coast Highway, some of us mad and some of us still, all of us enjoying the sunset over my first day in bedlam.

Suddenly the thought of all the magnificent things I'd bought overcame me. I had to share my enthusiasm with someone, so I pulled off the road at a phone booth to call Bronze Sydney.

Later, she said I sounded like a public-address system announcing departing trains. What I took to be wild enthusiasm, according to her, came out sounding half-dead: "Just described what you'd done in this dead monotone," she said. "I-went-to-the-trick-store. I-bought-yellow-pencil-sharpeners. I-am-very-happy ... like that."

"I sounded that creepy?"

"Yes. I thought you were doing one of your funny voices."

"What was I like when I got home?"

"Very pleasant and friendly. Back to your old self. Remember, the really bad things didn't start immediately."

Sydney liked the parrot and thought the other objets were a part of some labyrinthine plan I was cooking up. She was used to me arriving with whoopie cushions, joybuzzers, or boxes of toy soldiers which I'd take into my study and play with or stare at until the message I needed from them arrived. To her full credit, the woman didn't even bat an eye the time I spent a quiet evening at home gluing animal crackers together.

One image that's remained is of my wife's back as she carried two of the garden dwarves under her arms into our house. She was

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...