“Do you want to talk about Patterson now? We don’t have to if you’re not in the mood.”

Ruth Murphy’s face went through a whole Olympics of different expressions—anger, sadness, resignation—before she spoke. “Patterson the joker, right? The jokester, the clown, the idiot. That’s the Graham I knew. Back then, what wouldn’t the man do for a laugh? I assume you know about the time with the prosthetic arm? They were going to arrest him. They had him in handcuffs, for God’s sake! But he was so over-the-top goofy with the cops he made them laugh too, so they let the fool go. That time. There were others, and they didn’t end so happily.” She knew she wasn’t being fair or telling the whole truth because there were so many other things she had loved about Patterson. But now she was old and alone, and old love unfulfilled can sometimes fester.

The interviewer said gently, “But that was in his career as a comedian—long before he became famous and disappeared. You were together a long time . . . ”

“Three years. We stayed together because I loved him. You can love someone and still think they’re an idiot. I want to show you something.”

In the old woman’s lap was a battered, sun-bleached manila envelope. Opening it, she slowly slid out a large photograph. One side had a large crease, and overall the picture had not been well cared for. She handed it to James Arthur, the interviewer. He took one look and nodded—of course he’d seen it before. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of people had seen it before.

“That’s a very well-known picture, Ms. Murphy.”

“I know,” Ruth said irritably, having heard the condescension in his voice. “But it’s my line.”

“Excuse me?” Arthur straightened his back and tried to control the disbelief in his voice.

“He used my line—I said it. Or rather, I wrote it to him in a note, right after we broke up. Turn the picture over and read what’s on the back.”

The man did, and saw written there in handwriting that was instantly familiar to him:

“To Ruthie—who gave me the beginning with a Brownie. Thank you for that, and for so much more. Great Love, Graham.”

“Whoa, amazing! It’s hard to believe. I’m sure you know how famous this photo is—it’s on par with anything by William Eggleston. Personally, I think it’s better.”

Ruth grumbled “I didn’t say I took it—that was all Graham’s doing. The picture, the way he framed the image, the lighting, he found the location . . . it was all him. But the line itself was mine. I even remember writing it to him on a postcard.”

“Patterson would never say where the billboard was. It’s part of the mystery of the photograph.”

She touched her white hair, creating a little dramatic pause before spilling the beans. “Hallet, Nevada. Somewhere up in the Eureka district. Graham said it was originally called Hell It’s Nevada but they changed the name in the 1930s because the town was getting rich and the citizens wanted to make it sound more respectable. But when the silver mines nearby went bust in the 1950s, the place started dying and never stopped. In its heyday, everyone in town hung out at Mr. Breakfast. It was apparently Hallet’s social center.”

“Wait, wait—I’m writing this down. How do you know all this?”

Ruth Murphy moved slowly back and forth in her chair, trying to find a comfortable position. At least, one she could share more comfortably with her arthritis. The last days were closing in on her, and she knew it. She had no legacy, a son she hadn’t seen in two years, no business to pass on, and no life’s work she had created that would continue to exist after she was gone. Nothing to show the future world there had once been a woman named Ruth Murphy. No, she knew the only thing that might bring her a few footnotes in some biography or a line in an appendix was the fact she had lived with Graham Patterson before he became Patterson.

James Arthur handed the renowned photo back to her. She looked at it thoughtfully, pursing her lips.

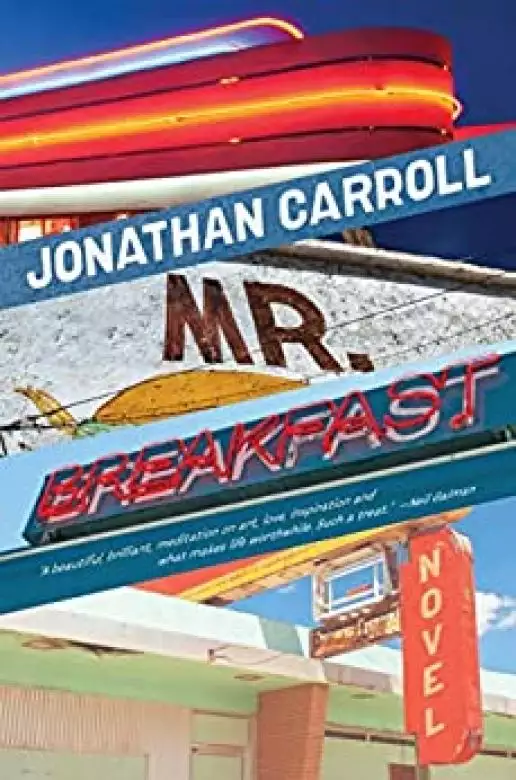

It showed a large run-down, vandalized, and badly boarded up salmon-colored roadside diner set alone on some bleak desert stretch of highway that looked like it could just as well have been on the moon. The first word to come to mind on seeing the image was forlorn. The diner had a long-faded red and white sign over the front door. It said “MR. BREAKFAST,” although two of the letters had fallen sideways over time, making the building look even sadder and more depressing. At the front of the diner’s empty parking lot was a giant weatherworn standalone statue of a smiling chef in a high toque holding up a tray with the name of the diner across the top. Below it, on the marquee sign where specialties of the house or community greetings like “Welcome Lions Club Members!” might once have been listed was a single sentence:

SOLITUDE CAN BE A MOODY COMPANION

In an early influential article about Patterson’s work, one art critic wrote what was so arresting about this photograph was because of the eerie way it was composed, it made a viewer feel the building itself was still somehow alive. The message on its giant sign was akin to a street beggar’s handwritten sign asking the world for help. Though, in the case of Mr. Breakfast, the place itself was saying, “I don’t want to be alone anymore.”

“Do you like the picture?” Ruth Murphy asked James Arthur.

“‘Mr. Breakfast’? Oh yes, very much. It was the first Patterson I ever saw, so it was the picture that got me hooked. Don’t you like it?”

The old woman sighed and thought a bit before answering. “I have mixed feelings. I can appreciate it as a work of art, famous image and all, but I also remember what was going on in Graham’s life then, and how much confusion he was in at the time he took it.”

-------------

It wasn’t supposed to happen like this. You buy a new car and it runs. It runs great for a few guaranteed years without anything going wrong. After that, but only then, is it allowed to break down—not in the first month of ownership. Not with only 2,695 miles on the damned machine, and most definitely not when you’ve just base jumped off the cliff of your old life into the great foggy unknown.

Could anything else go wrong in the Graham Patterson universe? His career—up in smoke. His love life? Down the toilet. His prospects for a rosy future? More likely to fit his fat body through the eye of a needle at that point.

The day after he bombed so badly at the comedy club in Providence, Rhode Island, Graham Patterson went to a car dealer and bought a brand-new, lipstick red Ford Mustang convertible right off the showroom floor. A check for five figures? Boom! Done. Next, he went to a camera shop and bought the Nikon he’d been lusting after for months because he wanted a photographic record of the trip he was about to take. He had a few thousand dollars left in his bank account afterward, which would get him across the country to where his patient and very successful brother Joel was waiting with a job, if he wanted it.

What Patterson really wanted was to be paid to make people laugh, but it was never going to happen. He accepted this fact now, and he had finally resolved to give the dream of being a famous comedian a decent burial during the trip. He’d been trying for years to make it, but after so long, knew in his heart it wasn’t meant to be. It was time to accept failure and make new plans for the rest of his life.

His father used to say, “There comes a point . . . ” Patterson had reached that point in Providence, the quiet murmur of the audience in reaction to his best comedy routine the final devastation. Added to this humiliation were the looks of indifference, impatience, and even derision on the faces of people who’d come to laugh but did not. To be fair, there had been some chuckling here and there, an amused snort or two and a few snickers at his best jokes, but big loud “ho ho!” laughs at Graham Patterson’s carefully crafted, torturously worked over act? De nada, baby. Nichts.

So he buried his life’s dream and drove away from that cemetery in the new convertible, which took him as far as North Carolina before it died, too. Luckily, the problem was only a defective fuel pump. It was covered under the warranty and could be fixed in an afternoon.

While waiting for the car to be repaired, Patterson decided to grab a bite to eat and take a walk around the town. Two pulled pork sandwiches and a large Royal Crown Cola later, he felt a tad better about the shape of his predicament.

A few blocks from the sandwich shop on a small, nondescript side street, he passed a tattoo parlor called Hardy Fuse. Thinking about it later, he didn’t know if he stopped to look in the window because of the odd name of the establishment or because of the photos on display in the store window. Patterson was no tattoo connoisseur or even much of a fan, but these were the most beautiful he had ever seen. Some were realistic, some abstract, but no matter where they were on the body, all of them were drawn and colored in such an arresting, singular way that it felt . . . it almost felt like the tattoos were speaking a whole new visual language to Patterson’s eyes and sensibilities. He had never seen anything like them before. He had to go into the place and investigate.

A bell above the door tinkled thinly when he opened it. Once he was inside, a low woman’s voice with a heavy Southern accent sang out, “Sorry, but we’re closed.”

Patterson hesitated, wondering why the door was open if the store was closed. A moment later the voice sang out again, “Just kiddin’. Hold on—I’ll be right out.”

Standing still, unsure of what he was going to say when this woman appeared, Patterson looked around—at nothing, really. There was little in the store to look at: a bare counter, a cash register, two scarred wooden chairs on either side of a cheap wooden coffee table. Some beat up National Geographic magazines were scattered across the top of it.

“Hello. How can I help you?” A small, pleasantly plain woman who appeared to be in her forties walked out from the back room of the store. Short black haircut, jeans faded and ripped at the knees, and a sleeveless fuchsia t-shirt that said “HEARTY FUSE” in large white letters across the chest. This confused Patterson, because he remembered the spelling on the store window was “hardy.”

“Are you hearty or hardy?” Patterson the wise guy asked, the jovial character taking over as he often did when in a tight or awkward spot. He’d learned over the years being funnily forward or sweetly aggressive with strangers usually amused them in situations like this.

The woman picked right up on what he was talking about and smiled. One of her front teeth was gold. “Well, sometimes it’s one, sometimes t’other. It’s like sometimes you’re in this mood, and sometimes that? Since I’m the boss and sole employee here, I decided to keep both. Are you here to get some ink?”

Patterson pointed to the shop window. “I’m here because while passing by outside, I saw those photos in your window and was knocked for a loop—they’re beautiful.”

She nodded her agreement—she knew they were good. “Want one?”

He wasn’t sure he’d heard her right. “Excuse me?”

“You want me to do one on you?”

Never in his life had Graham Patterson wanted or even considered getting a tattoo, although he liked some he saw on other people. But now that she asked and he’d seen examples of her great artistry, the thought intrigued him, and why not? Maybe this should be part of his new life—the new Graham Patterson, inked. “Can I see some of the others you’ve done? I mean, besides the ones in the window?”

“’Course! Let me get my books.” She put out her hand to shake. He noticed it was very small and chubby, like a baby’s. “My name is Anna Mae Collins. What’s yours?”

“Graham—Graham Patterson.”

“Well, Gray-yam, I’m going to show you some things now that’ll put new batteries in your flashlight. Have a seat.” She went to the back room again and reemerged holding two thick ring binders. Laying them down on the table, she gestured for him to take a seat. “I’m going out to get some coffee. You want one? While I’m gone, you look through my books and maybe find something in there you might want on your skin for-evah.”

He loved her slow Southern drawl and the fact she trusted him, a complete stranger, to stay put and not snoop around her place, or worse, while she was out.

As if she knew he would need time to look and linger over the choices, Anna Mae was gone quite a while. Patterson was amazed by what he saw in her books. The artistry, colors, the combinations of colors, the imagination and execution of that imagination . . .

Once, when things were going well between them, he and Ruth Murphy had taken a vacation in Mauritius. The thing he remembered most about the trip was the moment he stepped out of the plane at the Mauritius airport and smelled the night air. The first whiff was so gorgeous, so overpowering, but best of all so utterly foreign he just stood mesmerized in the doorway of the plane with eyes closed, sniffing. Seeing Anna Mae Collins’ tattoos for the first time felt a little like that.

“Your work is unbelievable. Where did you learn to do this?”

Anna Mae put a Styrofoam cup of black coffee in front of him and sat down in the other chair. “Here, there, everywhere. Art school, London, a mambabatok in the Philippines, Marseille, but I spent the most time in Japan . . . I wanted to know how to do it right, so I found out where the masters were and went to them. Took me seven years, and then I came back home. It was hard at first making ends meet, especially in this business, but people got the word about my work, and now they come from all over. Did you find something you liked in there?”

“I did.” Patterson had marked the page in one of the albums with a red plastic toothpick he had in a pocket. Turning to it, he pointed at one of the photos. Like the Russian matryoshka dolls, where one figure sits inside a larger one, which sits inside an even larger one, and so on, the tattoo he had chosen was of a bee inside the stomach of a frog inside the stomach of a hawk inside the stomach of a lion. What was most extraordinary about the image, besides the stunningly exact, almost photographic detail and coloring of each creature, was how small the tattoo was: insanely intricate interwoven imagery inside a space no larger than a pack of cigarettes, yet he saw clearly each figure and could only marvel at how perfectly every one of the creatures had been rendered. It reminded him of those oddball artists who paint pictures on the inside of matchbook covers, a rice kernel, or the head of a pin.

“This one. I’d like to have it right here.” Patterson patted his left bicep.

Anna Mae leaned in close over the page, studied the picture, and nodded. “Interesting choice. Two sessions, I’ll need two sessions to complete it. How long’re you staying in town?”

“Just today. I’m having my car fixed.”

“Stay the night. My mother runs a real nice bed-and-breakfast three blocks from here, and as a cook, she is out of this world. We call her the Queen of Tomato Soup. You’ll be glad you stayed, both for my tatt and her cooking. You in a hurry to get somewhere, Gray-yam?”

Patterson was not in a hurry to get anywhere. His destination was California, but he knew once there he’d either have to take the unwanted job in his brother’s fruit and vegetable exporting company or start looking around for something else he could do. Neither option excited him. So hell no, he wasn’t in a hurry. He slyly asked, “What’s Mom cooking tonight?”

Anna Mae nodded once and said, “Very good. Let me give her a call right now and ask. Then we’ll get started here.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved