- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

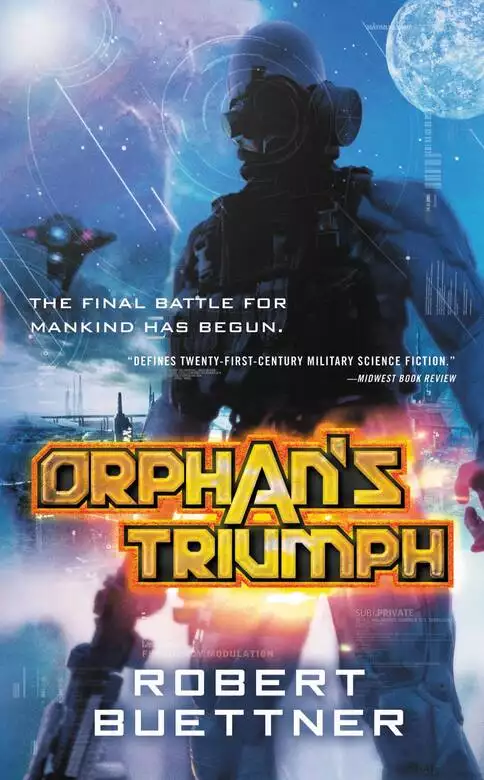

Synopsis

Jason Wander is ready to lead the final charge into battle. After forty years of fighting the Slugs, mankind's reunited planets control the vital crossroad that secures their uneasy union. The doomsday weapon that can end the war, and the mighty fleet that will carry it to the Slug homeworld, lie within humanity's grasp. Since the Slug Blitz orphaned Jason Wander, he has risen from infantry recruit to commander of Earth's garrisons on the emerging allied planets. But four decades of service have cost Jason not just his friends and family, but his innocence. When an enemy counter stroke threatens to reverse the war and destroy mankind, Jason must finally confront not only his lifelong alien enemy, but the reality of what a lifetime as a soldier has made him.

Release date: May 7, 2009

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 388

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Orphan's Triumph

Robert Buettner

The assault rifle’s burst snaps me awake inside my armor, and the armor’s heater motor, ineffectual but operating, prickles

me between the shoulder blades when I stir. The shots’ reverberation shivers the cave’s ceiling, and snow plops through my

open faceplate, onto my upturned lips.

“Paugh!” The crystals on my lips taste of cold and old bones, and I scrub my face with my glove. “Goddamit, Howard!”

I’m Lieutenant General Jason Wander, Colonel Howard Hibble is an intelligence Spook, and both of us are too old to be hiding

in caves light-years from Earth.

Fifty dark feet from me, silhouetted against the pale dawn now lighting the cave’s mouth, condensed breath balloons out of

Howard’s open helmet. “There are dire wolves out here, Jason!”

“Don’t make noise. They’re just big hyenas.”

“They’re coming closer!”

“Throw rocks. That’s what I did. It works.” I roll over, aching, on the stone floor and glance at the time winking from my

faceplate display. I have just been denied my first hour’s sleep after eight hours on watch. Before that, we towed the third

occupant of this cave across the steel-hard tundra of this Ice Age planet through a sixteen-hour blizzard. This shelter is

more a rocky wrinkle in a shallow hillside than a cave.

I squint over my shoulder, behind Howard and me, at our companion. It is the first Pseudocephalopod Planetary Ganglion any

Earthling has seen, much less taken alive, in the three decades of the Slug War, since the Blitz hit Earth in 2036. Like a

hippo-sized, mucous-green octopus on a platter, the Ganglion quivers atop its Slug-metal blue motility disc, which hums a

yard above the cave floor. Six disconnected sensory conduits droop bare over the disc’s edges, isolating the Ganglion from

this world and, we hope, from the rest of Slug-kind.

Two synlon ropes dangle, knotted to the motility disc. We used the ropes to drag our POW, not to hog-tie it. A Slug Warrior

moves fast for a man-sized, armored maggot, but the Ganglion possesses neither organic motile structures nor even an interface

so it can steer its own motility disc. Howard was very excited to discover that. He was a professor of extraterrestrial intelligence

studies before the war.

I sigh. Everybody was somebody else before the war.

Howard would like to take our prisoner to Earth alive, so Howard’s exobiology Spooks can, uh, chat with it.

That means I have to get us three off this Ice Age rock unfrozen, unstarved, and undigested.

I groan. My original parts awaken more slowly than the replaced ones, and they throb when they do. Did I mention that I’m

growing too old for this?

“Jason!” Howard’s voice quavers. He was born too old for this.

I stand, yawn, wish I could scratch myself through my armor, then shuffle to the cave mouth, juggling a baseball-sized rock

from palm to palm. Last night, I perfected a fastball that terrorized many a dire wolf.

As I step alongside Howard at the cave mouth, he lobs an egg-sized stone with a motion like a girl in gym class. It lands

twenty feet short of the biggest, nearest wolf. The monster saunters up, sniffs the stone, then bares its teeth at us in a

red-eyed growl. The wolf pack numbers eleven total, milling around behind the big one, all gaunt enough that we must look

like walking pot roast to them.

But I’m unconcerned that the wolves will eat us. A dire wolf could gnaw an Eternad forearm gauntlet for a week with no result

but dull teeth.

I look up at the clear dawn sky. My concern is that the wolves are bad advertising. The storm we slogged through wiped out

all traces of our passing and, I hope, kept any surviving Slugs from searching for us. But the storm has broken, for now.

I plan for us to hide out in this hole until the good guys home in on our transponders.

If any good guys survived. We may starve in this hole waiting for dead people.

We don’t really know how Slugs track humans, or even if they do. We do know that the maggots incinerated Weichsel’s primitive

human nomads one little band and extended family group at a time—not just by waxing the whole planet, which the Slugs are

capable of. And the maggots had rude surprises for us less primitive humans when we showed up here, too.

I wind up, peg my baseball-sized stone at the big wolf, and plink him on the nose. I whoop. I couldn’t duplicate that throw

if I pitched nine innings’ worth. The wolf yelps and trots back fifty yards, whining but unhurt.

Howard shrugs. “The wolf pack doesn’t necessarily give us away. We could just be a bear carcass or something in here.”

I jerk my thumb back in the direction of the green blob in the cave. “Even if the Slugs don’t know how to track us, do you

think they can track the Ganglion?”

Disconnected or not, our prisoner could be screaming for help in Slugese right now, for all we know.

Howard shrugs again. “I don’t think—”

The wolf pack, collectively, freezes, noses upturned.

Howard says, “Uh-oh.”

I tug Howard deeper into the cave’s shadows and whisper, “Whatever they smell, we can’t see. The wind’s coming from upslope,

behind us.”

As I speak, Howard clicks his rifle’s magazine into his palm and replaces it with a completely full one. I’ve known him since

the first weeks of the Blitz, nearly three decades now, and Colonel Hibble is a geek, all right. But when the chips are down,

he’s as infantry as I am.

Outside, the wolves retreat another fifty yards from the mouth of our cave as a shadow crosses it.

My heart pounds, and I squeeze off my rifle’s grip safety.

Eeeeerr.

The shadow shuffles past the cave mouth. Another replaces it, then more. As they stride into the light, the shadows resolve

into trumpeting, truck-sized furballs the color of rust.

Howard whispers, “Mammoth.”

The herd bull strides toward the wolf pack, bellowing, head back to display great curved tusks. The wolves retreat again.

Howard says, “If we shot a mammoth out there, the carcass would explain the wolf pack. It could make an excellent distraction.”

He’s right. I raise my M40 and sight on the nearest cow, but at this range I could drop her with a hip shot.

Then I pause. “The carcass might attract those big cats.” Weichsel’s fauna parallels Pleistocene Earth’s in many ways, but

our Neolithic forefathers never saw saber-toothed snow leopards bigger than Bengal tigers.

Really, my concern with Howard’s idea isn’t baiting leopards. Saber teeth can’t scuff Eternads any more than wolf teeth can.

I just don’t want to shoot a mammoth.

It sounds absurd. I can’t count the Slugs that have died at my hand or on my orders in this war. And over my career I’ve taken

human lives, too, when the United States in its collective wisdom has lawfully ordered me to.

It’s not as though any species on Weichsel is endangered, except us humans, of course. The tundra teems with life, a glacial

menagerie. Weichsel wouldn’t miss one mammoth.

So why do I rationalize against squeezing my trigger one more time?

I can’t deny that war callouses a soldier to brutality. But as I grow older, I cherish the moments when I can choose not to

kill.

I lower my rifle. “Let’s see what happens.”

By midmorning, events moot my dilemma. The wolves isolate a lame cow from the mammoth herd, bring her down two hundred yards

from us, and begin tearing meat from her woolly flanks like bleeding rugs. The mammoth herd stands off, alternately trumpeting

in protest at the gore-smeared wolves, then bulldozing snow with their sinuous tusks to get at matted grass beneath. For both

species, violence is another day at the office.

Howard and I withdraw inside the cave, to obscure our visual and infrared signatures, and sit opposite our prisoner.

The Ganglion just floats there, animated only by the vibrations of its motility plate. After thirty years of war, all I know

about the blob is that it is my enemy. I have no reason to think it knows me any differently. For humans and Slugs, like the

mammoths and wolves, violence has become another day at the office.

Howard, this blob, and I are on the cusp of changing that. If I can get us off Weichsel alive. At the moment, getting out

alive requires me to freeze my butt off in a hole, contemplating upcoming misery and terror. After a lifetime in the infantry,

I’m used to that.

I pluck an egg-sized stone off the cave floor and turn it in my hand like Yorick’s skull. The stone is a gem-quality diamond.

Weichsel’s frozen landscape is as full of diamonds as the Pentagon is full of underemployed lieutenant generals. Which is

what I was when this expedition-become-fiasco started, three months ago, light-years away in a very different place.

“HAS SHE SHOT ANYBODY YET?” I picked my way through the scrub and scree of Bren’s Stone Hills, wheezing. The planetologists said the Stone Hills were

analogous to Late Cretaceous cordillera on Earth, which didn’t make them easier to climb.

The infantry captain alongside me, burdened by his M40 and his Eternad armor, wasn’t even puffing. “No, General. But I’d keep

my head down. She’s not very big, but she’s the best shot in my company.”

We ran, crouched, as we crested the ridge, to a sniper team prone on a rock ledge. Below us the Stone Hills dropped away to

the east to the High Plains. In the early morning, moons hung in the sky like ghosts. One glistened white, the other blood

red, with a drifting pterosaur silhouetted against it.

Six hundred yards downslope, pocketed in rocks but a clear and easy shot from our high ground position, a figure in camo utilities

crouched among boulders. A hundred yards downslope from the soldier, a dozen Casuni tribesmen, sun glinting off their helmets

and breastplates, half surrounded her, screened from her by scrub. Each Casuni carried four single-shot black-powder pistols

huge enough to bring down a small dinosaur, and none would hesitate to use them. Really, the standoff just looked like a dot

sprinkle to me, because I was wearing utilities myself, without the optics of Eternad armor’s helmet.

The sniper’s spotter had his helmet faceplate up and peered through a native brass spyglass. He passed the glass to me and

pointed. “The Blutos chased her up there at sunset yesterday, General. You can see the snapper curled up alongside her.”

Through the spyglass, the dozen burly, black-bearded Casuni looked small. But the distant soldier looked about twelve years

old, gaunt, with hair like straw and big eyes. Her file said she was twenty-one, a private fresh out of Earthside Advanced

Infantry Training, with just two weeks on Bren. The snapper, its hatchling down as gray as the surrounding rock, was already

the size of an adult wolf.

I rolled onto my side, toward the captain. “What set her off?”

“Last week bandits ambushed the convoy that was shipping replacements out here from Marinus. Her loader bought the farm. He’d

been together with her since AIT. She took it hard.”

“He?”

“Nothing like that, sir. Infantry can be close without—”

I raised my palm. “I didn’t mean that, Captain. When I was a spec four, I was a loader for a female gunner. Just sounded familiar.”

The captain wrinkled his brow one millimeter. He was a West Pointer, and the notion that the commander in chief of offworld

ground forces was a high-school dropout grunt typically ruffled Pointers’ feathers. But maybe his discomfort grew from the

way I said it. Because I felt a catch in my throat. That long-ago female gunner and I had grown infantry-close, and in the

years later, before her death, as close as family.

The captain continued, “An adult female snapper dug under a perimeter fence and maimed three Casuni at the sluice before the

security Casunis brought her down. The private down there found the female’s cub wandering outside the wire. The private’s

trying to make a pet of it. But the Casuni say it’s sacrilege to let the cub live.”

Grown snappers are ostrich-sized, beaked carnosaurs. They’re quicker than two-legged cobras, with toxic saliva and the sunny

disposition of cornered wolverines. A snapper’s beak slices the duckbill-hide wall of a Casuni yurt like Kleenex, and Casuni

mothers have lost babies to snappers for centuries. Nothing personal. Snappers are predators, and human babies are easy protein

in a hard land. But in Casuni culture, even Satan is better regarded than snappers.

I sighed. “No animal-rights activists here.” Over the thirty thousand years since the Slugs snatched primitive Earthlings

to slave on planets like Bren, humans had adapted to some strange environments, none harsher than the High Plains of Bren.

The Casuni had evolved into flint-hard nomads, following migrating herds that resembled parallel-evolved duckbilled dinosaurs,

across wind-scoured plains that resembled Siberia. I turned to the captain. “Why haven’t you puffed her?” On Earth, any suburban

police department could neutralize a hostage situation by sneaking a roach-sized micro ’bot up close to the hostage taker,

then snoozing the hostage taker with a puff of Nokout gas.

“A creep-and-peep team’s inbound from the MP battalion in Marinus, sir. But it’ll be six hours before they ground here and

calibrate the Bug.”

As the captain spoke, two Casuni began low-crawling through a draw, screened from the girl’s sight, working their way around

toward high ground off her left flank. One of the Casuni must’ve been careless enough to show an inch of skin, because the

girl squeezed off a round that cracked off a rock a foot from the crawling man, exploding dust and singing off into the distance.

The girl called downslope in Casuni, her voice thickened by her translator speaker, “Stay away!”

I said, “We don’t have six hours.”

The captain shook his head. “No, sir, we don’t. That’s the only reason I set up a sniper to take her out. It makes me sick

to do it. But I know a major incident with the Blutos could freeze the stone trade.”

He was right. If the Casuni killed an Earthling, it would be a major incident that could jeopardize the fuel supply of the

fleet that stood between mankind and the Pseudocephalopod Hegemony. If the girl killed a Casuni, it would also be a major

incident. And given her advantage in skills and equipment, she was probably going to kill a bunch of them as soon as the Casuni

got in position, then rushed her.

But if we shot her, it would still be a major incident. The terms of the Human Union Joint Economic Cooperation Protocol, known in

the history chips as the Cavorite Mining Treaty of 2062, reserved the use of deadly force to indigenous civilian law enforcement.

Casuni civilian law enforcement resembled a saloon brawl, but I don’t write treaties, I just live by them.

I stood and brushed dust off my utilities.

The captain wrinkled his brow behind his faceplate. “Sir?”

“I’ll take a walk down there and talk to her.”

The captain stared at my cloth utilities, shaking his head. “General, I don’t—”

The sniper’s spotter swiveled his helmeted head toward me, too, jaw dropped. “That’s suicide. Sir.”

AFTER FIFTEEN SECONDS, the captain swallowed, then said, “Yes, sir.”

The spotter scrunched his face, then nodded. “I think there will be time if we take the shot as soon as she turns and aims

at you, General.”

“No shot, Sergeant.”

“Of course not, General. Until she turns and—”

“No shot. I’ll handle this.”

The spotter, the captain, and even the sniper stared at me.

Then the captain pointed downslope. “If the Casuni rush her, do we shoot? And who do we shoot?”

“The Casuni won’t rush her. That’s why I’m going now.” I shook my head, pointed at the sky. “It’s six minutes before noon.

At noon the Casuni will pause an hour for daily devotions. That’s our window to talk her down.”

The captain stood. “Then I’ll go, sir. I’m her commanding officer.” He rapped gauntleted knuckles on his armored chest. “And

I’m tinned up.”

I pulled him aside, then whispered to him, “Son, you’re right. If I were in your boots I’d be pissed at me for pulling rank.”

I tapped my collar stars. “But I need you up here to be sure your sniper doesn’t get the itch.”

I had given him a ginned-up reason, and he was smart enough to know it. But the captain was also smart enough and resigned

enough that he just nodded his head. There was no percentage in arguing with the only three-star within one hundred light-years.

Besides, he probably figured his sniper could take the shot before I could get myself killed, anyway.

Twenty minutes later, I had crept and low-crawled to within fifty yards of the girl and she hadn’t spotted me. Downslope,

I heard the twitter of Casuni devotion pipes. The warriors would all be head-down and praying for an hour, during which we

could clean up this mess, before they rushed her. I kept behind a rock ledge as I cupped my hand to my mouth. “Sandy?”

“Who the hell’s out there?”

“Jason Wander.”

“Bite me. The old man’s pushing paper back in Marinus. Whoever you are, I can’t see you, but I can hear you well enough to

lob a grenade into those rocks. So back off.”

“Sandy, I really am General Wander. I came out from Marinus to award a unit citation. When I heard what happened, I came here.

I’d like to talk to you.” I paused and breathed. “I’m going to stand up, so you can see me, see that I’m unarmed.”

“I’ll drop a frag on your ass first!”

Ting.

The M40 is an excellent infantry weapon, except that it makes a too-audible “ting” sound when it’s switched between assault-rifle

mode and grenade-launcher mode, as a grenade is chambered in the lower barrel.

So far, so good. My heart thumped, and I drew a breath, then let it out.

I stayed behind cover, levered myself up on my real arm, and glanced back to confirm where I was in relation to the sniper

farther up the hillside. Then I got to my knees, spread my arms, palms out, and stood.

The girl had swung around from facing the Casunis downslope and now faced me, her unhelmeted cheek laid along her rifle’s

stock as she trained her M40 on my chest. She lifted her head an inch, and her jaw fell open. “General?”

I nodded, then called, “Mind if I come closer? Then neither of us will have to yell. We won’t wake the baby.”

The voice of the captain upslope hissed in my earpiece. “General! Sir, you need to move left or right a yard or two. You’re

blocking the shot.”

Which was the idea, though the captain hadn’t anticipated it until too late. They don’t teach enough sneakiness at West Point.

The girl jerked her head, motioning me closer, but she kept her finger on the trigger. “Two steps! No more.”

I took the two steps, which brought me within fifteen yards of her, then shuffled until the distance between us was down to

ten yards.

She poked her M40 forward, then growled, a pit bull with freckles. “I said two steps, dipshit! Sir.”

In my ear, the captain said, “Sir, move left or right! Not closer! Now you’re obscuring her even more!”

The rifle quivered in the girl’s hand.

I swallowed. There’s a class in MP school that teaches how to talk jumpers down. I never took it. There was probably a series

of soothing questions to ask, but I didn’t know what they were.

So I said, “Tell me what happened, Sandy.”

“The Blutos tried to kill the baby.”

“And you’re tired of seeing things killed.” Even though her “baby” was a killing machine growing deadlier by the day. I kept

my arms out, palms open toward her as I inched closer.

“The other Blutos—the caravan raiders—killed my loader. I couldn’t do anything to stop it.”

“I started out as a loader. I was there when my gunner died, too. It’s an empty feeling.”

I wasn’t lying, either, about the feeling or the death. But my gunner’s death had come less than three years ago, though it

had come in combat and while I watched, unable to prevent it.

Her gun’s muzzle dropped an inch as she nodded. “It feels like there’s a hole in my gut.”

“The hole heals. It takes time, but it heals.” I didn’t tell her how much time, or how disfiguring the scar could be.

I stepped forward. The voice in my earpiece whispered, “Sir, the psyops people predict that she’ll shoot. Just kneel down

and we’ll take her out.”

She came up onto one knee, her M40 still trained on my chest. “What about the baby?”

I could see the snapper infant now, curled up asleep, tail over snout, on a bed of leaves the girl had prepared for it among

the rocks. Empty ration paks littered the ground, where the girl must have been hand-feeding the little beast. Regardless

of the girl’s maternal instincts, within a week the snapper’s predatory instincts would take over, and the monster would snap

the girl’s hand off at the wrist if she held out a snack. The exobiologists said snappers were the most implacable predators

yet discovered on the fourteen planets of the Human Union.

I said, “We’ll care for it for a while. When it’s old enough to fend for itself, we’ll release it into the wild.”

In fact, the Casuni would insist the devil’s spawn be gutted on the spot and its entrails burned. And with three of their

own maimed by the beast’s mother, we would have no choice but to turn the little snapper over to the Casuni like a POW.

Harmonious interface with indigenous populations wasn’t all handing out Hershey bars. Sometimes it required tolerating customs

we found barbarous. I used the moment to inch closer, within three yards of her. One step closer and I could lunge forward,

grasp her rifle’s muzzle, and twist it away.

Her rifle’s muzzle came up again and she snarled. “Liar!”

Crap. I’ve always been a lousy liar.

She fired, point-blank.

“SIR?” The whisper was old, gravelly, and familiar. It came from close to my ear, so I heard it over jet-engine shriek.

I opened my eyes, focused, and saw Ord, gray eyes unsmiling, and above him the interior fuselage ribs of a hop jet. I asked,

“Sergeant Major? What happened to the girl?”

Ord jerked his buzz-cut gray head, and I followed his eyes. A corpsman knelt beside the private, who lay strapped to the litter

next to the one I lay on. Her eyes were closed; her chest slowly rose and fell. Joy juice from a suspended IV bag trickled

down a transparent tube into her forearm. A purple streak began at the point of her jaw and traced halfway back to her ear.

Ord said, “Her jaw’s not broken, but you dropped her with a right as you went down, then landed on top of her. That kept her

outfit from shooting her and gave them time to get downslope and put cuffs on her.” Ord frowned. “Sir, if you don’t mind hearing

my opinion…”

I had minded hearing Ord’s opinion ever since he was my drill sergeant in infantry basic, but he never hesitated to share

it with me a. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...