- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In the bold, second installment of Buettner's military science fiction series that began with Orphanage, 25-year-old General Jason Wander is returning home after long years in space, but to what? Earth is now impoverished following the alien war. The problem -- the first alien invasion was merely Plan A.

Release date: April 1, 2008

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 324

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

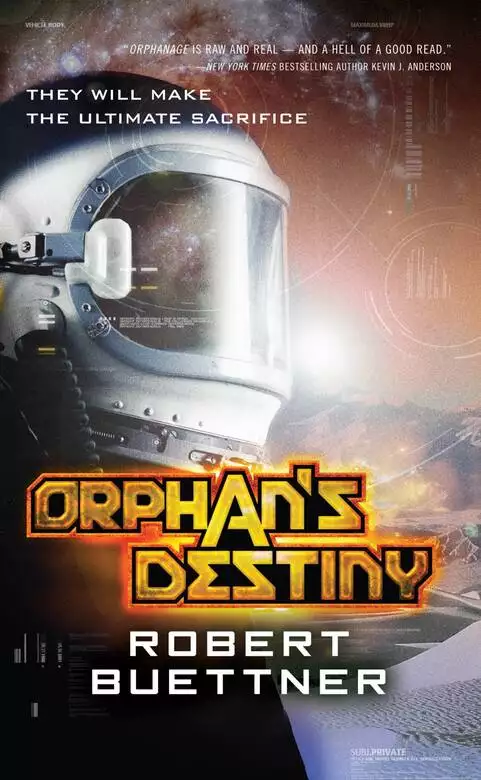

Orphan's Destiny

Robert Buettner

“ANYBODY OUT THERE? OVER.”

Static, not a human voice, cackles back through my earpiece.

Sssss. Pop.

Ten feet across this egg-shaped chamber, the hull-plate barricade I’ve thrown across the entry glows red. The Slugs are burning through their own ship to finish me. Roasted metal’s tang singes my nostrils. Two minutes, tops, then Slugs will surge through their opening like man-sized, armored maggots.

I reverse the pistol in my hand to use it as a club. The gesture measures my resolve. The pistol’s empty magazine well measures its futility.

I sigh and my breath worms out and glows purple in Slug interior lighting. Before my heart can beat, my helmet ventilator wicks away the condensation like a stolen soul.

My legs sprawl across the quaking Slug metal-blue decking and I thump my numb, armored left thigh with a gloved fist. Leg infantry needs two good legs. I could limp if I had to. But to where?

I let my back sink into the rescue-me yellow mattress of the Polytane hull-breach plug. That’s how we boarded this monstrosity, like pirates in Eternad armor, but the hull breach is no way out for me. Behind it stretches vacuum, the emptiness that fills space between Earth and the moon.

My visor display freezes the year in emerald digits at 2043. The timer, though, rushes down to four minutes and keeps falling.

When those timer digits spin down to zero, the human race will live or die. I die either way. I’m Jason Wander. For now, history’s youngest and screwed-est major general. For a while, a twenty-four-year-old lieutenant. For eternity, Infantry.

I’m also the human speed bump between the Slugs and Brumby. A mile beneath me in this beast’s belly, he may blow this invasion transport into rutabagas and both of us with it. If I can buy seconds here at the price of my life.

If we fail, Slugs by the millions will overrun Earth in slimy waves. Mankind will struggle, of course, with a brick-by-brick tenacity that will make Stalingrad look like a pie fight. The Slugs don’t know mankind yet, not when it’s defending its own turf.

The oval that outlines the Slugs’ emerging doorway glows white. We didn’t know they could do that. We know even less about them than they know about us. Soon, we may both know too much.

One minute left before they break through, just over three minutes until detonation, if ever.

My shoulders sag under my armor.

It has, all things considered, been a fine twenty-four years. I knew my parents, though not for so long as I would have liked. I grew up. I met good people. The best, in fact. I experienced the one great love of my life, albeit for just 616 days. I had a godson I came to love like my own child. Oh, and, depending on which version of history one read, I saved the world.

My ’puter beeps. Three minutes.

They say contemplation of death comes in phases: denial, anger, some other stuff, then, finally, acceptance.

Maybe that was the thing I had been luckiest about, compared to the other orphans I had known. A soldier’s destiny is to die young and unexpectedly. Soldiers often die nobly. Soldiers often die for others’ hubris or stupidity. But it is rarely a soldier’s destiny to have the time to accept his death.

The first molten metal plops, then sizzles, on deck plates as the Slugs burn through. I grip my spent pistol tighter.

In some alternate reality, there may be truth in the soldierly deception that war is bloodshed that brings life. I cock my head. That is, word for word, what the woman who bore my godson said when I delivered him in a cave on Jupiter’s largest moon.

That’s where this started for me, three years ago.

TWO

“YOU COULD BLEED TO DEATH!” I swiveled my head from the obstetrics instruction holo flickering to my left to the unladylike thigh-sprawl I knelt between. The field lantern’s Eternad-battery light cut crumpled shadows on the cave’s rock walls and ceiling. Zero Centigrade artificial atmosphere, manufactured by the Slugs we kicked off this rock seven months ago, numbed my fingers, slick with amniotic fluid and blood. A cave on Ganymede makes an awful birthing suite.

“No, Jason, this bloodshed brings life. Can you see the head, yet?” Corporal Sharia Munshara-Metzger puffed like a four-foot-eleven locomotive.

“Yeah. I think it’s crowning, Munchkin.” Whatever crowning meant. Four years ago I joined the infantry as a specialist fourth class, to stay out of jail. Fate and shrapnel had left me the acting commanding general of the seven hundred human survivors of the Battle of Ganymede. Obstetrics I knew like Esperanto.

I slid my eyes back to the holo. Bad enough to report the gynecological play-by-play without staring into the genitals of my best friend’s widow.

Through clenched teeth, Munchkin spat Arabic that I was pretty sure compared me, her acting commanding general, to something excreted by a camel. Eight hours’ labor erodes military courtesy.

She pressed her palms to her temples and thrashed her head side to side. Sweat droplets arced away from bangs plastered to her forehead, zero degrees or not. Her cheeks, olive and flawless, swelled as she puffed and blew. She focused her big brown eyes on me. “Why did we do this, Jason?”

Who we? What this? Women omit pronouns’ antecedents like aspen drop leaves in fall. But woe betide the man who fails to mind-read. I guessed. “Because the Slugs sat out here bombing the human race to extinction?”

She snarled. “I mean, why did Metzger and I have this child?”

I rolled my eyes at a question I had asked myself a hundred times during Munchkin’s pregnancy. United Nations Space Ship Hope had carried ten thousand male and female light infantry troops and five hundred Space Force crew for six hundred days from Earth to the orbit of Jupiter. The politicians weeded six million volunteers down to us lucky orphans who had lost entire families to the Slugs: “The Orphan’s Crusade.”

Even for orphans, unwanted pregnancy was a last-century relic, unheard-of since After-Pills. Yet only my best friend, the commander of the mile-long spaceship on which humankind had bet its future, and my gunner, after I introduced them, managed to break every imaginable regulation and conjure up a little nipper amid interplanetary combat.

Troubles find me like buzzards find roadkill. The Battle of Ganymede had been no exception.

A contraction stabbed Munchkin. “I must push.”

I shifted my eyes between the holo cube and her crotch. Munchkin’s Egyptian-pixie pelvis needed another centimeter’s dilation to pass a watermelon-sized human. I shook my head. “Not yet.”

The look Munchkin shot me made me glad it didn’t come from behind the sights of our M-60, but she didn’t push. For reasons I’ll never understand, the worse things get, the more people think I have answers.

I suppose that’s why I got field-promoted. As a specialist fourth class, I wasn’t even in charge of the machine gun I loaded for Munchkin. Now I was commander of this disaster. The politicians didn’t call it a disaster. They pronounced the battle a miraculous victory. The Battle of Ganymede will never be miraculous to us seven hundred survivors who buried ten thousand comrades beneath this moon’s cold stones. But the alternative was the extinction of the human race, so it was miraculous.

Before we lost Earth-uplink five months ago, the legislatures of our various nations sprinkled us with medals and promotions in absentia and promised us relief was on the way.

So, as acting commander, I was thinking up stuff for my remnant division to do while the cavalry rode four hundred million miles.

“Sir? Major Hibble on Command Net.” A shadow flicked across my view as my acting division sergeant major ducked into the cave behind me.

“Busy, here, Brumby.” I shifted my torso between Brumby and Munchkin’s privates. Stretched to nine centimeters, drained by eight hours’ labor, however, Munchkin could have cared less if she was appearing live on the frontscreen of the New York Times.

“They found something, sir.”

I turned. “What?” There were no more live Slugs. Certain of that, I had sent half of our force, including our surviving medic—the bastard had assured me Munchkin’s due date was two weeks away—with Howard Hibble to search for clues to what had made our now-extinct enemy tick.

To date we knew that Slugs had been a communal organism that originated somewhere outside the Solar System and turned up four years ago on Ganymede, using it as an advance base to bomb the human race out of existence city by city. We assumed the Slugs were galactic nomads, traveling in their entirety from planetary system to planetary system, sucking each system dry, then moving on.

The Slugs never confirmed or denied anything, they just killed people.

Every Slug warrior fought like hell until killed or cornered, then dropped dead to avoid capture. We’d been outsmarted, outnumbered, and slaughtered.

We won only because Metzger sent his crew to the lifeboats, then kamikazed Hope into the Slugs’ base in an impact so violent that Howard’s astroseismologists said Ganymede still twitched seven months later.

I’d agreed with Howard to march troops halfway around Ganymede not to find live Slugs. Metzger had killed them all off and wrecked their cloning incubators and destroyed their central brain. It—Howard insisted on referring to the Slugs as “It,” a single organism with physically disparate parts—was gone, over, obliterated.

Howard thought some of their hardware might have survived the impact. Somehow, these glorified garden snails had known how to air-condition a planet-sized moon, fly between star systems, and raise armies of infinite size and perfect discipline. They understood everything they needed to defeat us.

Except the perverse propensity of separate, individual humans to sacrifice ourselves for one another, by which Metzger had turned defeat into victory, for the price of his own life.

Brumby waved the handset at me, strawberry-blond eyebrows raised. Brumby looked like a freckled neoclone of a cowboy marionette I saw on a history chip, from the pre-holo TV days, named Doody Howdy or something. “TOT-uplink’s gone in two minutes, sir.”

I glanced at Munchkin. She lay still between contractions and nodded. Her husband had given his life to win this war. She understood that managing the peace was my job.

Brumby was twenty-four but combat had left him with a grandmother’s twitches. His fingers quivered while I swept my hands with a Sterilette, then pressed the handset to my ear. “This is Juliet, over.”

A blink’s hesitance separated question from answer as the signal relayed through the Tactical Observation Transport hovering line-of-sight-high between us.

“Jason, we found an artifact.”

I raised my eyebrows. Intact Slug machinery might hold the key to their technology. To date, we had recovered nothing but metal bits, plus Slug carcasses, personal weapons, and body armor. “What is it?”

“A metallic, oblate spheroid. Fourteen inches long.”

“A tin football?” For a grunt, I had high verbal SATs.

“Sixty pounds, Earth weight.”

“What’s it do?”

“Lies in a hole in the ground, so far.”

I squeezed the handset. “Howard, it’s undetonated ordnance! Get your people away from it!”

“We’ve never seen any indication that the Pseudocephalopod employed explosive weapons. It favored kinetic-energy projectiles. The engineers haven’t sniffed any explosives.”

“A human wouldn’t know a Slug bomb if it got stuffed up his nose!”

“We’ve already crated it. My hunch is it was a Pseudocephalopod remote-sensing device.”

The Army put up with Howard because his professorial hunches were usually right.

I sighed, then shook my head. “Howard, get your ass back here!” Our mission had never been to Lewis-and-Clark Ganymede. It was to destroy the Pseudocephalopod ability to make war on Earth from Ganymede. We had done that. Now, my job as commanding officer was to get my troops home, safe. If the Slugs had left behind a remote sensor, they might have left behind time bombs, Anthrax, or bad poetry. If there was a chance in a million that the Slugs remained a threat I didn’t want my force split like Chelmsford’s at Isandlwhana. Howard’s archaeological expedition was a dumb idea. “And leave that goddamn bomb right where it is!”

Static hissed back.

Brumby said, “We’ve lost ’em ’til the TOT repositions above the horizon, sir.”

Brumby retrieved the handset and trotted back to HQ, as gangling as the stringless puppet he resembled. Brumby had left Earth a high school senior with a genius for creating stink bombs and a belligerent propensity for setting them off in high school cafeterias. That had made him a combat engineer.

He would return to Earth, if we ever returned, an acting division sergeant major with post-combat yips.

“Now?” Munchkin growled through clenched teeth.

The instruction holo said that if I coached her to push too early, before she was fully dilated, she would exhaust herself. I hadn’t gotten to the part of the holo explaining what I had to do then, but I was afraid Dr. Jason would have to reach in there and pry the little rascal out. Or cut Munchkin open. I shuddered.

Sharia Munshara-Metzger was the closest thing to family I had. But as one soldier looking after another, I had seen her bleed before. And I had the remains of an infantry division waiting on my orders while I midwifed. What the hell. “Push, Munchkin.”

Ten minutes of screaming—by both of us—passed. Then I held my godson, as healthy as any squalling, purple prune with a cord growing from his navel. I swabbed mucus from his mouth and nostrils, then laid him across Munchkin’s belly.

While I tied off, then cut, the umbilical cord, I asked, “Did you pick a name?” I knew she had, because every time I had asked her over the last seven months she looked away. Munchkin had a Muslim superstitious streak as wide as the Nile. I figured she was afraid she’d jinx the kid if she said a name.

“Jason.” Munchkin’s smile glowed through the subterranean twilight.

“What?” I swallowed a lump in my throat, even though I’d half guessed the name. Munchkin, Metzger, and I were all war orphans. Ganymede was our orphanage and we were our own family.

“Jason Udey Metzger. My father was Udey.”

I adjusted my surgical mask, so I could wipe my eyes without seeming to. “People will call him Jude.”

People would call him more than that. The Son of the Savior of the Human Race. The Spawn of the Exterminator of the Universe’s other intelligent species. The only Earthling conceived and born in outer space. The Freak.

“Jason, this is the best day of my life.” Tears streamed down Munchkin’s cheeks and she sobbed so hard that Jude Metzger bounced on his mother’s belly like he was rafting class-three whitewater.

I understood. But I thought that for me the best day would be the day we all left Ganymede.

I was wrong.

THREE

ON THE MORNING OF OUR 224TH DAY on Ganymede, measured in Earth days, Jude Metzger celebrated his one-week birthday under Jovian skies. But the Ganymede Gazette, the daily paper my guys published on the backs of old ration wrappers, had a bigger headline.

For 223 days Ganymede’s skies didn’t change. The daily, orbit-induced windstorms whirled golden dust above the mountains. Beyond their peaks and the dust clouds shone stars and Jupiter’s visible lesser moons, Europa, Io, and Callisto, some days pink, some days pearlescent or violet against space’s indigo. Over all loomed ever-orange Jupiter, at each rise and set magnified by the artificial atmosphere’s lens so the gas giant filled the horizon.

We all watched the sky every one of those days. Not because it was beautiful but because there lay home.

On the morning of day 224, at five-zero-three Ganymede Standard Time, Brumby burst into the mess cave, binocular range finder in one freckled hand, the other pointing back over his shoulder.

Brumby didn’t have to speak. Only one thing would excite any of us interplanetary castaways like that.

Egg-scrambled (concentrated) tubes and therm cups clattered to the frozen lava floor. Before the echoes stopped rebounding off the cave walls and ceiling, three hundred combat-boot pairs thundered out into pale twilight.

I let the men clear out, then followed them onto the rocky terrace that Brumby and the surviving engineers had blasted out of the mountainside. Architecture on Ganymede involved blowing things up, since we had three building materials to work with: rock, rock, and rock.

By the time I got outside, someone, not Brumby who stood alongside me to avoid trampling, had picked it out. I simply let my eyes follow the pointing fingers.

Just a luminous fly crawling toward us across the deep purple ceiling of our world, but the prettiest sight I had ever seen. The relief ship. Maybe.

Brumby turned to me. “Sir, how long you figure before the first of us gets off the rock?”

“First question is how we make sure we all get off, Brumby. Order alert status.”

Brumby stiffened. “Sir? Alert?” Brumby and seven hundred cold, exhausted, lonely GIs figured it was party time, not jump-in-our-holes time.

It may be no coincidence that “General” and “Grinch” begin with “G.” Alert status meant the troops dispersed to fighting positions. “Disperse” meant walk, crawl, and climb. Three things GIs had bitched about since Troy.

Well, there were, historically, two schools of military thought here. Concentration of force, like the Romans huddling in phalanxes, shoulder-to-shoulder and shield-to-shield, or dispersal, spreading troops out so one grenade couldn’t get a whole squad. Short, the general in charge of the Army Air Corps at Pearl Harbor a hundred years ago, huddled all his aircraft together so they would be easier to guard. And created perfect targets for Japanese bombs.

So I was a dispersal man, myself. Even if my grunts hated it. The sooner we fled this rock the sooner I could shed the stars on my shoulders and slide back to being a grunt, myself. Oh, I hoped they’d let me keep a lieutenant’s bar. But presiding by default over an accident had made me no general officer.

“Brumby, all we know is that speck is somebody coming. Might be relief. Might be Slugs. Pass the word to the battalion COs.” The Ganymede Expeditionary Force’s surviving “battalions” weren’t much more than platoon-sized, maybe fifty soldiers each. Word-passing would take Brumby sixty seconds.

Brumby half shook his head, denying the possibility that there might still be Slugs, more than questioning my order.

“Brumby, if it’s our guys, they’ll be in field-strength radio range in a couple hours.” Generals—even field-promoted spec fours—didn’t need to justify orders to their aides. Maybe it was my way of telling him I wanted that speck to be our guys, too. “The men can break out the potato vodka then.”

Brumby’s jaw sagged. Surely he had realized I knew about the still? During the six-hundred-day voyage out here from Earth, one of Howard’s lab techs had hidden his booze-making equipment and his potato raw material in a Hope escape pod, never expecting he, the pod, and his still would wind up dirtside, stranded among the embarked-division survivors.

Brumby grinned, then saluted. “Yes, sir.”

While Brumby passed the word, I cupped a hand over one ear and radioed Howard. “Hotel, this is Juliet. Say your estimated time of arrival and position. Over.” Dispersal didn’t mean having half your force miles away.

“Jason, it’s Howard. We’ll be back there in an hour. At least that’s what they tell me. I’m not sure where we are. Did you see it?”

Howard land-navigated like a blind Cub Scout but I should have known he would have spotted anything that moved in space. I said, “You think it’s our guys? What if it’s Slugs?”

“The Pseudocephalopod displaced between conventionally mapped spatial locations by transiting temporal-fabric folds.”

“In English, Howard.”

“Slugs jumped through worm holes that join points where space folds back on itself.”

“Another hunch?”

“It had to be that way. Stars with planetary systems are too far apart to be reached by conventional travel at sub-light speeds. Even if It lived a long time.”

“Okay. So?”

Howard continued. “So, if It still existed, for which we have no credible intelligence, It would most likely appear to us in a way we never expec. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...