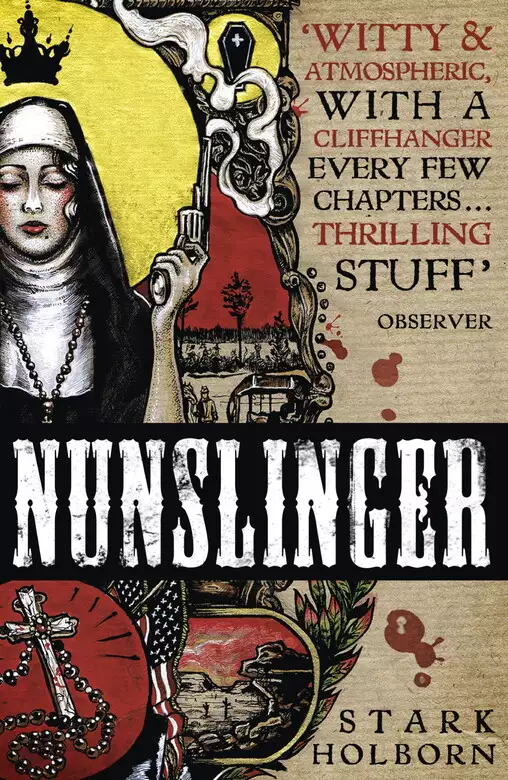

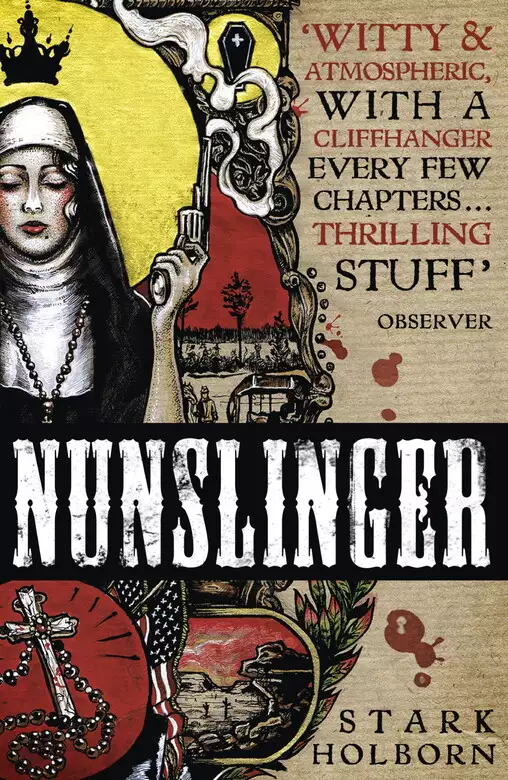

Nunslinger: The Complete Series

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The year is 1864. Sister Thomas Josephine, an innocent Visitantine nun from St Louis, Missouri, is making her way west to the promise of a new life in Sacramento, California. When an attack on her wagon train leaves her stranded in Wyoming, Thomas Josephine finds her faith tested and her heart torn between Lt. Theodore F. Carthy, a man too beautiful to be true, and the mysterious grifter Abraham C. Muir. Falsely accused of murder she goes on the run, all the while being hunted by a man who has become dangerously obsessed with her. Her journey will take her from the most forbidding mountain peaks to the hottest, most hostile desert on earth, from Nevada to Mexico to Texas, and her faith will be tested in ways she could never imagine. Nunslinger is the true tale of Sister Thomas Josephine, a woman whose desire to do good in the world leads her on an incredible adventure that pits her faith, her feelings and her very life against inhospitable elements, the armies of the North and South, and the most dangerous creature of all: man.

Release date: December 4, 2014

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 624

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Nunslinger: The Complete Series

Stark Holborn

I am like a broken vessel

For the first mile, I was too terrified to open my eyes or look around. My ears strained for the slightest sound of pursuit, though it was only Rattle’s hooves that echoed back from the canyon walls.

Another mile and I was able to raise a calm eye to my surroundings. What I saw was not welcome. Barren gutters of land, sides dropping away steeply only to rise again.

‘Where are we?’ I managed to ask Muir at last. My voice was dry as a husk, subdued by the silence of the place.

‘Badlands,’ he coughed. ‘Runs for miles. Nothing but rock a’tween here and the plain.’

It was then that I saw it, a slow bloom on the shoulder of his jacket, spreading in a dark patch where my hand had rested until a moment before. I looked at my fingertips. They were sticky with blood.

‘Abe?’

‘I know, Sister.’

‘We must stop.’

‘Another mile. We ain’t safe yet.’

But it was only a half-mile, less even, before the wind started up and drove us from the path. It roared down the length of the canyon, whipping the dust around us in stinging tongues until I could neither hear nor keep my eyes open. I felt Muir slip then, and reached around to take the reins myself, guiding Rattle toward the lee of a great stone. Here was some shelter, and I breathed a prayer of thanks as I pulled Abe from the saddle.

Once he was settled, I checked the state of our provisions. It did not take long. The canteen of silty water, grown stale in the sun; one square of hard tack; a chunk of salt pork. It would not last us a day.

Muir was watching me with his shrewd, dark gaze, his arm hanging limply at his side. He seemed barely to notice the blood that had begun to drip from his wrist onto the earth below. I closed my eyes for a moment and tried to pray. But I was afraid. I did not want to die in such a lonely place, with none to mourn or remember the woman who was flesh above scattered, bleached bones.

I fought my way through a simple prayer, one from childhood. By the time I had finished, strength filled my limbs and my head was clear once more. I looked to the man at my side.

With some persuasion, he drank first from the canteen. I followed suit, a few sips only to moisten my throat, although I made show of swallowing mouthfuls. An honest deception, I hoped. Next, I eased off the hide jacket. His face flashed white but he did not cry out. Neither did he vomit from the pain and lose the precious few mouthfuls of water, for which I was grateful.

At last I could see the wound. A hole the size of a nickel, its edges ragged.

‘I shall have to remove your shirt, Mr Muir. If I might borrow your knife?’

‘Why, this is my best shirt, Sister. You’ll leave me with naught but a burlap sack to cover my decency when we get to town.’ He attempted a grin and I smiled in return, although I could not help but notice the way his mouth shook.

The nurse in me took over then. I searched through the packs until I had what I needed; laying out the knife, tin of matches and, after some hesitation, the box of bullets. Carefully, I cut away the fabric and used a spare cloth to sop up some of the blood. My jaw clenched; the bullet could not be seen. Neither had it passed through the flesh on the other side.

‘I know it’s in there, Sister. Can feel it like a tooth stuck in deep.’ Muir turned his head awkwardly and swore. ‘Enroy did not intend to take me alive.’

I had heard of the techniques for treating bullet wounds from a group of Benedictines who ran a hospital boat on the Mississippi. They talked of amputations, of survival rates being high – if treated with proper care. In St. Louis I might have been able to retrieve the bullet and stitch the wound, bathe it in clean water and dress with cotton, but here I was as helpless as a child. I pushed away the anger that threatened my composure and thought hard.

‘Mr Muir, I am going to search for the bullet. I shall need you to stay awake. Can you do that?’

A laugh cracked in his throat. ‘Sure can.’

His head lolled against mine as I probed the skin of his back. His neck was tanned to a deep, bark brown, the muscles in his shoulders lighter, like two different wood grains, running together. Yet I was not prepared for what I saw below: from shoulder blade to waist the skin was scored with shiny pink scars, raised like the stripes on Enroy’s waistcoat. I knew the marks of a flogging when I saw them, but held my tongue.

I could feel the bullet, hard beneath the surface of his skin, which was hot to the touch. With a breath, I drew the tip of the blade over the flesh in a narrow cut. Muir bucked for a moment and bit down on the leather sheath I had given him.

With the tip of the knife I explored the wound. Metal scraped on metal – it was not deep enough yet. It was needful that I work quickly, before the pain became too great. In one movement I pushed the knife tip in deeper, levered it back. Metal came into sight; I levered again and it was out.

Muir was groaning now, the hair at the nape of his neck soaked with sweat. Of what came next I had no experience, and even less confidence. I had read of the practice, but out here, with only the roughest of supplies, what I intended to do seemed barbaric.

‘My Lord, grant me the grace to perform this action with you and through love of you. I offer you in advance all the good that I may do and accept all the pain and trouble that I may meet as coming from your fatherly hand.’

I reached for the box of bullets. Muir stiffened; I am sure he guessed for what purpose I needed them.

‘Sister, please, you can’t . . .’ his voice was thick with pain.

‘Abraham Muir. I ask you to trust me. The Lord will help me in my work. I shall not let you die here.’

I would not let him speak further, but ripped the shell from the casing with my teeth. Inside was the black powder. I tipped it into the cavity of the wound, as much as it would hold. My hands trembled. I could barely shake out a match in order to strike one on the rock. Before I could think better of what I did, the flame touched the powder in Muir’s flesh.

The crack that followed stunned me, throwing me back. Muir screamed in the same instant, then slumped forward. There were scorch marks on my hands, and one cuff of my habit smoldered. I took the knife and hacked off my sleeve at the elbow.

The wound was horrific, blackened and oozing sluggishly. I began to fold strips of the torn habit, binding his shoulder. I tied the final knot and sat back on my heels. My body betrayed me then. I turned and retched from the nerves and the blood and the smell of burned flesh. It was quite some time before I felt composed enough to check up on my patient. He was slumped where I had left him, face slack with pain. Although he shook violently, his eyes were open.

‘Sister,’ he was motioning weakly toward his blanket roll.

I unbuckled it. A grubby bottle tumbled out into the dust. I did not hesitate, but pulled the cork, held it to his lips. He drank as much as his mouth would hold.

‘Bend an elbow, Sister,’ he wheezed. ‘I won’t tell.’

For the first time in my life, I felt the sear of whiskey in my dry throat and I thanked God.

CHAPTER TEN

The cleanness of my hands before his eyes

‘Sister?’

Gaze to gaze we stood, separated by a weapon. For a moment, it was as if the walls did not exist, and we were once more travelers upon the plain, sharing fire, sharing hope. Yet without were my hunters, and within . . . I felt the heat rise to my cheeks as I recalled the bare chests of Muir’s companions.

‘Sister,’ repeated Sarah, ‘we were told you was locked away.’

‘Paxton is here,’ I stooped to retrieve my makeshift weapon, relieved to be free of Muir’s eyes. ‘There is a marshal with him; they are searching the building.’

‘We got to get you hid,’ she told me, pulling up her dress. ‘They’ll come for sure—’

‘What in God’s name are you doing here?’

Abe’s words dropped into the room like a blade slicing fat. Even in the half-light I could see there was a flush upon his face. I fought to regain my composure, but could not dull the edge of my voice.

‘I might have asked you the same, should I care to dwell upon the answer.’

He opened his mouth indignantly, but any reply was cut off by a shout from outside, the shadow of feet beneath the frame. I found myself being pushed against the wall, out of sight behind the door. Muir too was being hustled away.

‘Stay quiet now, you hear, stay real quiet,’ hissed Sarah.

The door flew open, but she was ready.

‘What is the meaning of this?’ she demanded, hands on hips. ‘We are entertaining, as well you know.’

The light from the corridor fell upon the scanty gown, barely covering her shoulders. There was something of a pause as more than one man groped around for his voice.

‘Got an order to search this place. Looking for a fugitive, dressed like a nun, as may be.’

I heard someone take a few steps into the room. I noticed then the drops of blood from my hand had stained the rough floor, marking a trail that led straight to me. I was barely able to hold my breath steady, but the man seemed to have stopped at the sight of the bed.

Abe was sprawled in only his shirttails, the second girl spread languorously across his lap. For a moment his mouth hung open, staring at me in my place of concealment. Despite the shock and the fear I almost laughed.

‘Got two girls,’ Muir announced loudly to the room in general. ‘Two of ’em, for twice the . . . doings.’

‘As y’all heard, we been engaged,’ the girl continued, drawing closer to the door. ‘But if you boys care to return later, we’d sure like the company.’

‘Taking the coach straight to Carson,’ coughed the marshal, retreating. ‘Y’all watch yourselves and tell us if you see anything. ’S a murderer we’re after.’

Then he was gone, the door shut, a chair wedged hurriedly beneath the handle.

I felt Muir’s eyes upon me.

‘A murderer,’ he repeated slowly. ‘Something to tell me, Sister?’

CHAPTER TEN

And vows are to be paid

I soon discovered that the editor of the Denver Rancher was right: once Templeton took an idea into his mind, he was not to be dissuaded. Reluctantly – for it seemed the most promising way to gain access to Windrose – I agreed to his plan. I would abandon my rough trousers and buckskin for a gown and bonnet.

The newspaperman offered his credit to pay for my clothes; an apology he said, for the falsehoods he had written about me. I did not know from where he had obtained the funds, and I feared their source was less than honest.

If Muir had been there, he would have snorted with laughter and told me to bide myself; that such things as unsavory sources of money were upon Templeton’s own neck. I had not seen Abe for more than a day, not since our quarrel at the bar. His absence troubled me.

Meanwhile, Templeton had procured the garments I needed, arguing that he had greater experience of a lady’s wardrobe than I. I allowed him to choose what he would, so long as it was modest.

When the time came, I shed my shabby clothes. The calico and hide from the plains had become my habit, I realized; they had shielded me, sustained me. The new garments felt like a costume. When I first donned them and turned to the looking glass, I did not recognize myself.

A demure blue dress with voluminous sleeves covered me from ankle to wrist to my neck, there secured by a silk scarf to conceal the scar that circled my throat. There was a bonnet, decorated with pink false flowers, and Mr Templeton had instructed me to comb out my short blonde curls so that they fell upon my temples and hid the scar there too. Lastly, he had helped me into a pair of lace gloves and dusted my face liberally with a pot of powder, tutting that I was ‘too sunburned for a lady’.

He was delighted with his efforts, and once he was satisfied he began scribbling in his notebook, glancing up at me from time to time, telling me that he always suspected I was a great beauty, until I was forced to ask him to refrain from speaking. He too had made himself presentable, his whiskers finely trimmed and waxed once again, a new shirt beneath the old plum waistcoat.

‘We shall take a turn about the town,’ Templeton reassured me, setting his arm beneath my gloved hand, ‘so that you might accustom yourself to your costume, ma’am.’

As we descended the stairs, my feet, encased within tight, buttoned boots, were unsteady. The scent of the powder he had applied was overpowering, until I thought that I would not be able to breathe through it.

Templeton dragged upon my arm as we walked, chiding me for striding so boldly, telling me I should not stare about me so, as though I was being hunted.

‘It is a difficult custom to break,’ I muttered, as we crossed the thoroughfare.

‘Templeton!’ a voice shouted, and my heart began thudding. It was Abe. I did not know what to do with my hands as I heard his familiar steps approach. ‘Templeton!’ he said again, bounding up onto the sidewalk, ‘I have been askin’ about, and have found—’

He stopped dead at the sight of me. I struggled to meet his eyes.

‘Mr Muir,’ Templeton hissed, glancing about him, ‘if we are to speak in public then I must insist you greet the Sister as one might a lady. We cannot know who is watching.’

With a black look, Muir inclined his head stiffly.

‘I found them two hard cases,’ he said to Templeton, ‘Buxton and Hayle, what the Sister said were at the ranch. Saw them loiterin’ around Main Street, by this fancy-lookin’ carriage. The man in the stables were indisposed to let on who they were, but I persuaded him some.’

There was a graze upon his cheekbone, I noticed, and his knuckles were swollen. He tried to hide them behind his back as he surveyed me. ‘Thought we might’ve taken them on ’stead of prettying up, but I see I am too late.’

‘Was it Miss Windrose’s carriage?’ I demanded, flushing at his tone.

Muir nodded. ‘That’s what the man said. But I don’t see—’

Before he could finish, I ducked away from Templeton and hurried out onto the street. My heart was loud in my ears as I stumbled past horses and barrows, hampered by the dust and my skirts. Upon the next street, a fine four-wheeled carriage stood near the sidewalk, pulled by a pair of sleek bay horses, its black lacquer shining beneath a sprinkling of dust.

A woman was emerging from a building, her hands busy with a pocketbook. She was immeasurably elegant, a dark blue bonnet and veil shading her face, a silk dress that rustled as she stepped onto the running board of the coach. I felt a strange surge of envy as I looked upon her. The two men Abe had mentioned were already in position, one perched upon the back, the other in the driver’s seat.

With a deep breath I tripped up to the window of the carriage, dragging a handkerchief from my pocket at the same moment.

‘Miss Windrose?’ I announced. ‘I believe you dropped this.’

CHAPTER TEN

Besides what is hid within

‘Matthew Hopkins,’ the farmer told me, coming forward to shake my hand. ‘That there’s my wife Susan, and our girl Kitty.’

I reached out to take the proffered hand, only to find that I still held the pistol. Flushing to the roots of my hair, I shoved it back into my waistband and clasped his hand with my own. It was strong, despite his age, and rough with calluses.

‘What the hell is going on here?’ Puttick exploded, glaring about the room. He held the rifle before him. ‘Where did she come from?’

‘Hello, Colm Puttick,’ Owl greeted calmly, blood still dripping off her knives. ‘I thought you did not like him?’ she asked me.

I leaned around to look at the pair of men they had captured. Hayle was groaning and cursing, blood coursing from the side of his head. Buxton glowered, his teeth gritted. There was a ragged hole in his upper thigh, surrounded by scorch marks and leaking gore.

‘I did not think it would fire,’ Kitty told me shakily, hefting the old musket. ‘It were my granddaddy’s. I packed it with buckshot . . .’ she leaped back as Hayle lunged. Hopkins struck him with the butt of the rifle.

Puttick and I kept the pair in the sight of our weapons while Owl and the others set about tying them, hand and foot. When they were finally secured, Puttick swore, lowering his gun.

‘Now will someone tell me what in Sam Hill is going on?’

‘Better fetch Templeton,’ I sighed.

By the time darkness fell, we sat comfortably within the farmhouse. Outside, a cold breeze rolled down from the mountains, making the stars shiver. The family shared what they had, and we drank tea, ate bread and lard before the hearth. It would have been cosy, were it not for the loaded weapons beside each plate; the pair of wounded ruffians tied in a corner, letting out a curse or a groan every so often.

‘I followed them,’ Owl chewed, gesturing to Buxton and Hayle with her spoon, ‘after the Patterson ranch. You run off, back to town but these two I follow. It was not difficult. They are lazy. All the way to that big house in the mountains, I watched them. Like a hawk,’ she grinned, and Hayle snarled, thrashing in his ropes. He fell still when three weapons were leveled at him.

‘Many times, I could have killed them when they slept,’ she told me, ‘but I thought, they will go after others. And when they do . . .’ she shrugged.

‘What she is not saying,’ Hopkins said matter-of-factly, ‘is that she rode ahead of them, when they stopped at noon. Damn near flogged her horse to death doin’ it, damn near got a bullet in her gut as well, ’til she took off her hat. We was expecting you to attack, see,’ he said to me, and I felt my face begin to burn with anger, ‘but she warned us, told us what was what. That it weren’t you coming, but these two.’

‘Mr Windrose made an offer for our land,’ Susan told me, ‘a few month back. It were generous enough, but this is our home. Matthew worked ten year to get enough money for these acres, an’ near another ten farming them. We ain’t leaving. We told him as much.’

‘Then came the stories, ’bout other settling folk gettin’ killed down south, but we never thought—’

‘That they had refused to sell too,’ my head sank to my hands. ‘Five hundred miles of land to be cleared of homesteaders, and only one person in the country who could kill so many without motive.’ In the silence I listened to my heartbeat, to the shifting of ash in the grate. I raised my head to look at Miss Windrose’s men. ‘All to be certain of her claim. She will not stop, will she?’

Hayle only sneered at me and spat.

I was on my feet, had the gun to his head before I even knew what I was doing. I stared at him, pale and bloody beyond the pistol’s length. All the fragile cheer of the hearthside was gone as I barked out that one question which plagued me, drove me.

‘Where is Muir?’

Hayle’s lips lifted into a smile.

‘You won’t do nothing,’ he said. Confidence oozed from him as he settled back against the wall, blood stained as he was. ‘You never killed a man in your life.’

‘I asked you a question.’

Hayle only snorted up a ball of mucus and spat again.

I raised my eyebrow.

‘Owl,’ I called over my shoulder, ‘did you cut off his ear?’

Stony faced, the woman nodded, brushing strands of black hair back from her face. ‘You want me to cut off the other one?’

I opened my mouth to respond when a force struck my shins, sending me tumbling to the floor. The pistol flew out of my grip, and in an instant, Hayle attacked, pinning me to the boards with his body as his bound hands grappled for me, thumbs plunging toward my eyes.

A flash of silver, a dark shadow above and warm blood exploded onto my face. Hayle’s body went limp as he opened and closed his mouth emptily, life flooding from the sundered arteries of his neck.

Hands grasped my shoulders, and Puttick dragged me free from under the body. I swiped the blood from my eyes. Templeton and the Hopkins family looked on, grim-faced. Susan offered me a rag.

‘Did you have to kill him?’ I asked Owl, scrubbing at my face.

The dark-haired woman pursed her lips and began to clean her knife.

‘We need only one of them to tell us where to go.’

Every pair of eyes turned toward Buxton, who was gazing in alarm at Hayle’s lifeless corpse.

‘North,’ he blurted, ‘up near Stout. I do not know if Muir is there,’ his eyes were fixed upon Owl’s knife, ‘but that is where she will be. It is the start of the railroad.’

CHAPTER TEN

Dark waters in the clouds of the air

The climb was relentless. Steeper and steeper the gulches rose, the cliff face falling away like a yawn of fear on one side of the narrow trail. The path turned to fine dust and loose stones, making the horses’ hooves jerk and slip.

Pokeberry fell twice, each time more heart-stopping. I could not endure the thought of him breaking a limb, so I dismounted and led him by his bridle. Abe shouted back at me not to be a fool, but Rattle was faring little better and soon he too was on foot, struggling toward the distant summit.

Fear was coursing through my body. My head pounded, and my ribs were one spasm of hurt from where the blast had thrown me. I prayed none were broken, yet there was no time to stop and make certain. The cut across my collarbone bled sluggishly, but mercifully did not seem deep.

A chill grew in the air, hard in my gasping lungs. All at once the great, eyeless crags were looming above us. Sentinels of the Lord sent to crush me and to reveal the sins upon my soul. They called to me hungrily. My knees buckled in awe and dread and the knowledge that I was to die, that they would take me to meet my maker.

The cold brought me to. I spluttered as Abe threw away the handful of snow.

‘Air,’ he wheezed, white with his own difficulty. ‘S’rare up here; look straight ahead, try and stay calm.’

We were at the snowline now and I thought we might finally be safe. But Muir’s eyes squinted to the peaks, up into the sky where, magnesium-white, the sun was swallowed by cloud. In the harsh light, every line on his face seemed magnified. So too his years, his sins and sorrows, until he stood thrice-aged before me.

‘Fast,’ he whispered. ‘We got to move fast.’

It was not only men we were fleeing – flesh and blood and armed with fire – but a storm.

The fog rolled in as the temperature plummeted. The cold was thick and insidious, creeping through seams and buttonholes to chill the skin beneath. Oftentimes, I could only make out the slipping shape of Rattle’s back hooves, and nothing of his master, but I pressed on, following their trails in the growing frost.

Ice, a hard crust over snow that never melted, began to send me to my knees. I had no gloves, unprepared as we were for the cold, and soon my palms were scraped raw. Abe’s wheeze drifted back to me. I murmured a prayer of resolution, of strength, and began it again each time I fell.

‘Dear Lord, give me courage, for I lack it more than anything else. Give me strength, against men and their threats . . .’

A faint cry was all the warning I had before it struck. I had seen blizzards in St. Louis, yet only ever from the safety of the convent. This was fierce: a blast with crystals in its depths, not fine and sparkling but smashed into shards. After one minute my skin was screaming, after another, my hand came away flecked with blood. I dragged the kerchief from my neck, wrapped my face as best I could. Poor Pokeberry’s mane was heavy with icicles, frost creeping into his nostrils. I tried to brush them free but found the bridle frozen in my hand.

I had begun the prayer again when I fell hard, my boots skidding out, sending me crashing twenty hard-won paces back down the mountainside. Pokeberry slipped with me, his hooves clattering dangerously near my head, the whole weight of him ready to crush me in one breathless second.

I thrashed my way to a stop. The reins had come loose from my hand and I prayed the horse had found his feet. My muscles screamed in protest as I tried to rise, eyes flooding in pain. I blinked them clear, but a moment later my eyelids were freezing closed.

The mountains, which had seemed so glorious only a short time ago, were cold with condemnation. I cried out, and the peaks took even that, swallowing my voice without even the hint of an echo. There was no sight, no sound, no air left for me. Just pain and cold and the weight of the sky upon my limbs.

Different pain, sharp, hard upon my cheek! I clawed at my eyes, but still they were sealed closed. There was a brushing against my wind-stung face and I felt warmth, faint and whipped away, but settling again and again, until the crystals began to give.

One eye came free, then the other beneath my scraping fingers.

Muir cradled me, breathing the warmth of his living body upon my face, melting the ice from my eyes. His hands held my head and for one, illimitable moment I felt as safe as a child.

Yet the storm raged and there was pain and he pulled me roughly to my feet, the frost cracking in the creases of my clothes.

Stay with me, his look said, black in the face of the tempest. Stay with me, or we perish.

CHAPTER TEN

As a moth doth a garment, and a worm the wood . . .

I must have fallen insensible once more then, for I recall little of what passed next, save for Abe’s arm around my waist, and a narrow wooden corridor. The cool fabric of a pillow met my cheek and I sank gratefully onto the bunk, only to rise again in panic.

‘No,’ I protested, struggling upward, screwing my eyes against the light that spilled through the brass porthole. ‘No, I cannot.’

‘Sister, you’re done in, look at you.’

I pulled at the ribbons holding the bonnet, until they came loose. Abe hissed when he saw my scalp. My eyelids were heavy, but I fought to keep them open.

‘Concussion,’ I told him, swallowing back nausea. ‘You should not let me sleep.’

‘What in God’s name? Did he do this, that man?’

‘The soldier? No, he was kindness itself.’

I managed to tell Muir of what had passed in the alleyway, one or two words at a time. The pain made me retch, until I could not continue.

‘Stupid woman,’ Muir growled, though his hands were gentle as he pushed me back. He woke me again minutes later, dabbing at the wound with a damp cloth. I felt the blood that was crusted around it give way beneath his ministrations.

‘Here.’ A glass was at my lip. ‘Brandy and opium, best I could do from the ship’s medicine chest. They’ve no doctor aboard.’

I had never had cause to use opium myself, though I had administered it on many occasions, but the pain was so great I swallowed the liquor down in a gulp.

‘A cold compress will help,’ I told him, and he began to dampen the napkin again.

‘Those bastards,’ he murmured, as he pressed it carefully onto my scalp. ‘Hurtin’ a lady like that.’

Perhaps it was his tone, the lightness of his hands as he smoothed the cloth, but at once I felt as though everything was crumbling away, sand in a flood. Sorrow broke upon me, and I had nothing with which to hold it back.

‘What’s this?’ Muir questioned, and I knew then that I was sobbing, chest shuddering and tears flowing as if they would never stop. The world was tearing at me on all sides, clawing at my faith, my strength, at my very being, until there would be nothing left save the raw meat of my soul.

‘You’ve weathered worse than this, Sister. A bang to the head won’t kill you.’ His voice was gentle.

‘It is no use,’ I choked out, ‘no use in going on. They will destroy me.’

‘You know that ain’t true.’ Abe’s face floated above me. His brown eyes, for once, were entirely unguarded. They claimed my attention, until I was able to gasp in one long breath, then another.

‘You have work to do,’ he continued, ‘an’ the strength to withstand this.’

He pushed my rosary into my fingers, and closed my hand around it with both of his own.

The opium and brandy were working, for the edges of my vision had softened into shadows. Dimmer and warmer the room grew, until the tears from my eyes slowed, only now and then tracing my cheek.

‘Tell me a story,’ I whispered, as the world opened around me. ‘Please, tell me of something good.’

‘Ain’t much good ever happened in my life, Sister,’ Muir sighed, and his words seemed one with the motion of the sea that swayed the bunk. ‘There were the Injuns, then the ranches, the war . . .’

‘One good time?’ I murmured.

‘Sure, there’s one,’ he said after an age, so long that I was unsure whether I dreamed. ‘Bright as a new penny it is, when I call it to mind, even after all these years.’ His voice grew younger as I listened, losing its sullen edge, its reluctant rhythm.

‘There were a dance, one town over. Grand affair – can’t recall the cause, but it were a great excuse for merriment. Whole town an’ more beside were out in the streets. The start of summer it was, air fresh as new grass. Warm too, enough to roll up your shirtsleeves an’ feel the night on your skin.

‘Group of us lads from the ranch went into town, lookin’ for trouble and to drink ourselves silly, truth be told. But instead I found her. Jus’ as soon as we rolled into town I saw her, leaping about in a dance beneath them little flags and burnin’ lights in the dark. Her hair were the color of aspens in fall: a great stream of it

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...