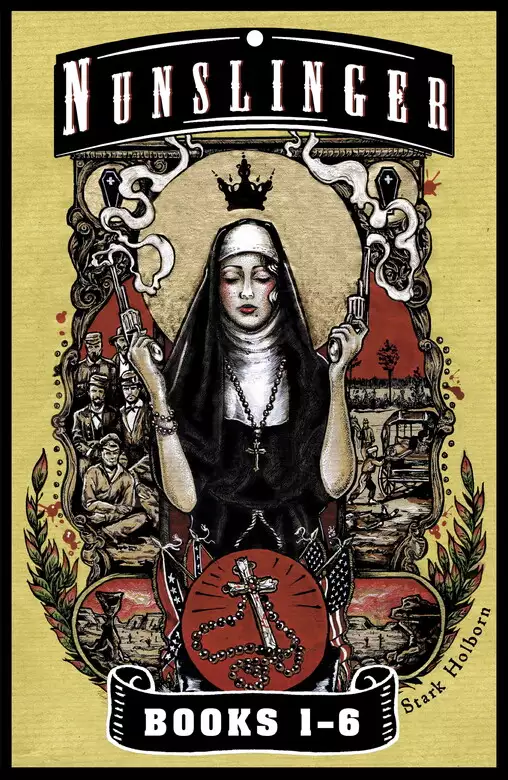

Nunslinger - The First Omnibus

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The year is 1864. Sister Thomas Josephine, an innocent Visitantine nun from St Louis, Missouri, is making her way west to the promise of a new life in Sacramento, California. When an attack on her wagon train leaves her stranded in the Nebraska Territory, Thomas Josephine finds her faith tested and her heart torn between Lt. Theodore F. Carthy, a man too beautiful to be true, and the mysterious grifter Abraham C. Muir. Falsely accused of murder she goes on the run, all the while being hunted by a man who has become dangerously obsessed with her. Her journey will take her from the most forbidding mountain peaks to the hottest, most hostile desert on earth, from Nevada to Mexico to Texas, and will be tested in ways she could never imagine. Nunslinger is the true tale of Sister Thomas Josephine, a woman whose desire to do good in the world leads her on an incredible adventure that pits her faith, her feelings and her very life against inhospitable elements, the armies of the North and South, and the most dangerous creature of all: man.

Release date: March 13, 2014

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Nunslinger - The First Omnibus

Stark Holborn

Moreover, my reins have corrected me even till night

Dusk found us camped by a small pond, which was just as well, for Muir’s canteens had been dry since noon and thirst claimed my throat. Although I had counseled myself to accept the feeling of dust within my lungs, of dehydration and dryness in every pore, I could not deny the relief I felt at the sight of water.

Muir stared at the pool for a while, then he took up his rifle and plunged the wooden butt in, swirling it like broth.

‘Nothing dead in there,’ he pronounced after a time. ‘Fine to drink, like as not.’

He freed Rattle of bridle and pack, and the horse headed straight for the water. Muir let him drink for a time before hauling him back.

‘There’s proof Sister, if you needed it. Best fetch the canteens.’

The water was full of silt, gritty on the tongue but clean enough. A haze had fallen on the evening, as if someone had swiped a wet cloth over the landscape’s colors, made them bleed and run. This suited us, Muir said, for it meant the smoke from our fire would not be so evident.

He refused still to answer my questions about when I should be reunited with the wagon train, or indeed, why they hunted him so, for we were clearly being followed. In the heat of the afternoon we had overtaken Carthy and his men, but from our high vantage, I had made out several flecks of blue and brown scouting the foot of the plateau for a path.

‘Nothing to see, Sister. Ain’t another way up nor down for miles.’

It was only the second time he had acknowledged the Bluecoats’ proximity. Press him as I might, he would say nothing further. Instead, he set about unpacking the evening meal. I watched carefully, and calculated. There were few provisions left.

‘Fine meal tonight,’ he called. ‘Beans and salt pork and all the dust you can eat.’

He upended a sack into his pot, shook out the crumbs. There was barely enough for a child.

‘Mr. Muir, we have bypassed Carthy and his men. How much longer do you propose to detain me as your ‘insurance’?’

As before, he made no answer, but continued to clatter about with his spoon. I set my feet more firmly.

‘Very well, a simpler question. How will half a heel of salt pork and a few canisters of silt last two persons any longer than a day before they starve in this wasteland? I am no fool, Mr. Muir. There is a trading post or a station that cannot be more than half a day’s ride from this place and you intend to call there.’

A muscle was twitching beneath the line of his jaw. My mind warned me to take care, yet I was flushed with anger and stubbornly continued.

‘Whatever this place is, post or stable or telegraph stop, there you shall leave me, sir, and be on your way. That way I shall cost you no more misery, and can re-join Lieutenant Carthy.’

‘Good God, woman!’

Muir was on his feet, eyes dark as mahogany just inches from my own. His face was pale with anger.

‘I had thought to escort you as far as the town of Medicine Bow, five days hence – five days out of my way I should add – so that you would be spared the risk of encountering that hard-case. Yet you’re yearnin’ for him like a cat in heat. Well, I shall leave you at the trade post as you desire, though I won’t prepare you for the sort of men you will encounter there. It seems you are set on engaging with the worst of them.’

Muir’s good humor thus evaporated, he strode off across the plateau, leaving me alone in the gathering gloom. I felt the kind of heat that precedes tears, and gulped them back. I confess I was shocked. It had been a long time since I had been spoken to thus. Muir had never before raised his voice.

If it was his intention to escort me across the plains, I had just abandoned the safety of a guide for a remote post. Yet I could not reconcile his words in relation to Mr. Carthy. I could not help but think that such anger might stem from jealousy or intolerance rather than truth.

I sighed and climbed to my feet. My own conduct had been unseemly and I determined to rectify matters before Mr. Muir and I parted company. But he was back, before I could move a step, his face calm. He held his hat under one arm and squinted off into the distance. I noted for the first time several streaks of gray in his nut-brown hair, though he could not have been any more than thirty.

‘I raised my voice to you, Sister Thomas Josephine, and for that I am sorry. I’m not accustomed to company out here, least that of a woman. I brought you from the wagon trail for my own ends, an’ so I’ll not refuse to leave you safe.’

He sounded like one of the children at the convent school, reading an apology by rote. Speech done, he looked me in the eye.

‘You’re a damn fool if you choose to remain at the post, but I won’t hold you against your will, Sister.’

I smiled then, for here was the man I had grown accustomed to.

‘I accept your apology, Mr. Muir.’

He nodded, knelt by the fire, and set about trying to salvage his pot of beans.

‘Allow me.’

Gently, I took the pot and spoon from his grip.

‘You ever try beans and molasses, Mr. Muir?’ I asked, realizing as I spoke that I was mimicking his drawl in my own, long forgotten Southern tones.

His cigar-end smile was slow to emerge, but when it did he turned it upon me in full.

‘Can’t say I have, Sister. But I reckon you’ll be wanting the sugar.’

CHAPTER EIGHT

The reproach of men, and the outcast of the people

Slowly, the water around me became tinged with pink, like the sky at dawn. I scrubbed and scrubbed every inch of my skin, ridding it of the dried blood. I had sat there for more than an hour, the bath water growing cold around me, but I could not yet bring myself to leave.

The act of washing had renewed me, recalled to mind the presence of the Lord and his healing power. Slowly, I drew the washcloth from fingertip to elbow, praying that my sins might thus be stripped from me. Eyes were watching my lips, the soundless pattern they made.

The women were ranged around like birds, perched on every surface, gazes fixed upon me. All the brothel’s residents, save for June. She I had not seen. Nettie had been given a spare bed for the time being, and had fallen asleep almost as soon as a blanket had been settled over her.

The need to wash had been paramount in my mind. Face coloring, I lowered the cloth with a splash. My request for privacy, peace, for a bowl of cold water only, had been overridden, and now I sat before them, an exhibition in a tin tub.

‘Might there be soap?’ I managed to ask, with as much dignity as I could muster. There was a great scramble then, as one, then another, produced hard chunks. Some were perfumed with violets, worn to slivers, but I chose the most humble, rough and homemade, such as we might have produced in the convent. I turned my body away from them as best I could and scrubbed at my hair until my fingers were sore.

I did not realize that the room had fallen silent until I sluiced the last of it from my scalp and looked up. June stood in the doorway, her face as unreadable as it had been in the jail. I wondered how long she had been watching me. Deliberately, her eyes lingered over my body, head and face, my ribs, showing through my skin. I closed my arms over my chest, wishing for some shield from the scrutiny.

‘Paxton were here,’ she announced, as if bored. ‘Wanted to search the outbuildings. I don’t believe he suspects nothing, but he’ll be back; he ain’t a total ass.’ Her address took in the rest of the women then, ranged about the room. ‘She’s got one day. At dawn tomorrow she’s out, hear?’

A murmur of assent ran through the room. Then she was gone, the door swinging behind her.

‘Don’t mind her, she din’t want none to do with it,’ one of the younger girls said in a burst, coming forward with a sheet. ‘Said it were too dangerous but rest of us were for it.’

I took the cloth gratefully, and rose from the water, wrapping myself shoulder to ankle. The women crowded around, their powder and perfume surrounding me. I had not been wholly secluded from the world in St. Louis, and had sometimes seen women of the night on the streets there, but never to speak to up close.

Now, their loose dresses, corsets and bared flesh were enough to make me blush, so I looked instead into their faces. Beneath the rouge and shadow I was relieved to find eyes that could have belonged to any woman, curiosity and good humor in their expressions.

‘Nettie raised the alarm,’ a woman I remembered was called Sarah told me, gathering up my habit. ‘Scratchin’ at the back door like a stray cat. Said we were the only ones to speak to her… after. Course we knew she were with child. Whole town knew.’

‘Wade, he beat on one of the girls, ‘bout a year back,’ whispered the youngest woman, dark eyes wide. ‘Beat her so bad her head ain’t right now. June wouldn’t let him in after that, so guess he started getting his fix on the kid.’

‘Not one person in this town sorry to see him gone.’ Sarah’s voice was like flint, and the other women fell silent. ‘Not one, save for Paxton. Don’t matter none who killed him.’

One by one, they began to drift away, for the night had run on into the early hours of the morning. Several stayed behind, the youngest mostly, pressing me for details of Wade’s death, of my journey west. Yet I was long past conversation, and soon, disappointed, they too bid me goodnight.

Finally I was left alone. It could not have been far from dawn, then. In the convent, I might have been rising from my bed, making my way to the chapel in order to say Lauds, in readiness to greet the Lord and a new day.

I knelt to pray, and found my eyes drawn to the threadbare rug beneath my knees. The room must have belonged to one of the girls, for it was decorated with scraps of dyed cotton and lace, paper flowers in a vase. I was drawn to the bouquet, and stared at the stiff leaves and petals; at the center of the arrangement was a blue rose.

Even in the dim light its color drew me in, petals like jewels, brighter than any flower that could grow on earth. A memory of the cold, of blooms in the snow, and of eyes…

I snatched my hand away. Fatigue was pressing heavily, so I lay on the bed. My prayers came halting, and every time I began to drift into sleep the sight of Wade’s ruined face assailed me. I rubbed at my arms, for even the touch of eiderdown seemed cold and damp, like flesh.

Come to town to judge us, June had accused. Who was I to judge, who had lied, had hurt and walked a path of death? I did not deserve comfort, even of a narrow bed.

It was only when I lay myself upon the cold, bare boards of the floor that Wade’s face sank in my thoughts and sleep claimed me at last.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Who teacheth my hands to war

The hours that followed passed in a blur. I remember not whether I sat and prayed or paced the fort like a woman with a demon at her heels. It was not my place to intervene in the carriage of justice, I told myself over and over, until the words became confused with the litany I recited.

Muir had killed - the Indian child, the sergeant, and the stranger at the trading post - were they not also Christian souls who deserved an answer? Carthy too: were the innocent lives he ordered taken present on his conscience or was he merely a pawn of duty? Muir had said he reveled in the deaths, but Muir could lie.

Sundown dropped silently and swiftly upon the fort. With every moment the general drew nearer. Finally, I could withstand my anxiety no further and resolved to pit my conviction against the truth. I was so consumed by my thoughts, that I paid no heed to the time, or indeed the routines of others. It was only when I knocked at Mr. Carthy’s study door and was told that he was occupied with dressing that I realized the unsociable hour of my call.

I made a swift apology and retreated, mortified by my self-indulgence and preoccupation.

‘Sister?’ Carthy’s voice rang out down the hallway. ‘Please do come in, I am decent, if not wholly presentable.’

Cheeks burning, I entered the room. A private was dispatched for a jug of lemon water. If Mr. Carthy was as embarrassed as I, he made no show of it. He was sat at his desk before a large pile of goods. He was jacketless, gloveless, and it struck me that I had never before seen his hands bare. They seemed peculiarly white against the tanned skin of his neck and face.

‘To what do I owe your call, Sister?’ he smiled, buttoning his cuffs. ‘I am afraid that I cannot be entirely at your disposal. As you know, the general is expected.’

‘Mr. Carthy, it is I who should apologize. I came to ask...’ My voice trailed off as I saw what was piled on his desk.

Through a jumble of reins I saw familiar inlaid wood; Muir’s pistols. The sight of them was like a recrimination and set my heart pounding. I could not ask for Muir’s pardon, it was not my place. It was my calling to see the Lord’s presence in the world at every turn, not to cry and whine if I did not like what I saw.

‘Sister?’

I remembered the pearl rosary in my pocket, clasped the excuse it gave me gratefully, and extended it to him.

‘I am touched by your generosity, Mr. Carthy, but I cannot accept such a gift. It is not appropriate for a humble servant of God as myself. I would return it to you before I leave.’

I laid the beads gently on the desk. Carthy’s smile seemed sad.

‘I should have known that would be your wish. I had hoped you would bear away some piece of this place with you when you left, close to your heart.’

In the small room the scent of his clothes, his skin, was overpowering. I clasped my hands before me so that he might not see their trembling. But his eyes seemed to take in all. Again, I thought of flowers, impossible blue paper roses that I had seen as a child.

He was speaking. I had to force my attention back to his words.

‘It would however, please me greatly to see you wear it once. It has not been worn since my mother passed. She would appreciate its continued use.’

It has not seen much use at all, a small part of my mind hissed, or the gold would be worn away. I pushed aside such ill-natured thoughts and assented.

‘My thanks, Sister.’ He said, his smile warm.

He held up the rosary. The pearls gleamed in the falling dusk, and for a moment I thought of the faces in the infirmary, pale moons in a row of beds. I reached out my hand, but Carthy shook his head.

‘Allow me.’

He came close enough for his sleeve to brush against my cheek as he lowered the string. For a long moment, his hands lingered. I could not hold that gaze any longer, so closed my eyes to begin my prayer.

‘Credo in Deum Patrem omnipotentem, Creatorem caeli et terrae...’

But the words, ordinarily of great comfort to me, were only words; I could not make them mean anything. Carthy’s presence was strong. I heard a whisper of cloth and fingertips touched my cheek. The prayer faltered. I opened my eyes then and was little better than frozen as his lips moved to meet mine.

Then I saw it. Upon his palm were marks, angry and red, peppering the skin like a hundred tiny bites. Most would have dismissed it as a rash; leather chafing from long days spent holding reins. Yet I was a nurse and had seen the marks of syphilis before, long advanced.

My recoil was instant. Carthy still held my gaze. I glanced away, quickly, near ripped the rosary from my neck in haste to be rid of it.

‘I must go now,’ my voice shook as I turned and dropped the beads onto the desk. ‘I shall take up no more of your time.’

I had not even heard him move, but the sound of the key turning in the lock was audible enough.

‘Yet you enjoyed our talks so much. I am hurt that you would leave with such little gratitude for your host.’

The blood began to pound in my ears. The fort buildings would be empty, company, staff, all assembling on the parade ground to welcome the general. I could hear the commotion beginning to filter through the window. I spun toward the glass, reached for the latch, but Carthy’s hand closed about my wrist. I could feel the infection hot against my skin.

His other hand was tugging at my veil. I fought him off as best I could.

‘You will not touch me, I am a Bride of Christ,’

‘You are a woman. You are no more than a woman.’

His hand had caught on Muir’s rosary and it swung out into the open. It was enough to deflect his attention for a moment as he laughed.

‘You prefer his pagan trinkets to mine. What of my crimes, Sister? Shall I not be forgiven?’

He pushed me backwards and I struck out, my nails catching him across the lip. A scratch only, but enough to break his hold. I lunged for the desk, for Muir’s pistols there, pulled one free from the pile.

‘Not loaded, Sister.’

Carthy was coming toward me, one hand to his bleeding mouth. There was a box of bullets on the table, I snatched them up as I backed away, but my hands shook so much that I spilled all but two. I had only a moment before Carthy reached me again. This time, I raised the pistol.

‘Unchristian of you,’ he smiled. ‘This violence does not become you, Thomas Josephine.’

There was a cry from outside then, many voices, the scream of a horn; the general had arrived. I armed the gun, in one move.

‘A full pardon for Mr. Muir.’ That knife-hard voice was mine. ‘Safe passage to the next state. Or the general shall know of your vile intentions.’

‘The general will not treat you with such care as I have done.’ Carthy’s smile was curling into a snarl. He placed his hand over the muzzle of the pistol.

‘He will take you without qualm and without recrimination. What other man could order the slaughter of three hundred innocents, and not a word from Washington? Death is needed where law demands it. Muir shall die. It is God’s will and it is mine.’

I caught the sound of boots, marching in formation and knew my time had run out. Clenching my teeth, I looked him dead in the eye.

‘You presume to know God’s will, Mr. Carthy, but you cannot know mine.’

I pulled the trigger.

CHAPTER SEVEN

He bowed the heavens and came down…

The morning came, sun rolling red over the mountains. In its wake trailed a colorless sky, the moon ghostly upon its surface. The riders brought the mist, rising up from the night-damp earth to tangle about feet and stirrups.

They dismounted a distance from the cabin, leading their horses silently over the frost-covered ground. A wail pierced the still morning.

‘They found her,’ I murmured. ‘Come, we must hurry.’

I kicked Pokeberry into a trot. We had climbed a hill that rose above the cabins, the jut of the land hiding us from sight. On the other side I was pleased to see a small creek: the water would serve to hide our trail.

‘What did you do?’ called Muir over the sound of water on rocks.

‘Nothing the Lord will not forgive.’ I replied. ‘She will not have been harmed.’

‘That was not how it sounded,’ grunted Abe.

‘The only thing they’ll hurt, no doubt, is her pride. I do not believe she took kindly to having her hair shorn.’

After a few moments the silence was punctuated by great laugh, clear and sudden, and I looked back to see that cigar-end grin I knew so well but too seldom saw. I could not help but laugh in return, my heart lifting for the first time in many days. We splashed across the creek, Rattle balking at the icy water, and I related how Jessie had planned to betray us.

‘As soon as we were asleep she must have run to the teamsters in the barn and asked them to ride to town for the bounty hunter. I caught her red-handed. I am afraid your hat was a casualty of battle,’ I explained, for my head was now bare. ‘It was necessary that she look enough like me in the darkness to fool them for a few moments.’

‘So you lopped off those pretty brown curls of hers?’ Muir laughed.

‘I hope it will teach her some humility. ’ I justified calmly. ‘The Lord knows, her father deserves some peace.’

‘Little cat,’ he cursed, ‘going against her pa’s word an’ all…’

‘You should not blame her for what she did,’ I pulled Pokeberry up alongside, in order to see his face. ‘Their need was great.’

‘I’ve seen worse suffering, Sister, and by those who’d pull their own teeth afore they’d break a vow.’

There seemed little use in pressing the matter, and I will admit, I did not want to dwell upon it. The new day’s air was fresh, a welcome relief after the poverty of town and cabin. The mountain pines rose steep and green into the foothills, and the sky wheeled out, a high, unbroken blue. A kind of elation took me, the like I had rarely felt, a simmering in my chest. With a deep breath, I dug my heels into Pokeberry’s flanks and he took off, pounding the pine needles into the earth, their resinous scent trailing behind us through the deep forest.

‘Was it the man that Jameson warned of?’ questioned Abe, when we had once more slowed to a walk. ‘The “devil” in furs?’

‘I am not certain. Jessie said that the teamsters had mentioned a name. It was strange, I recall, a flower perhaps—’

I had to haul on Pokeberry’s reins to prevent him colliding with Rattle. Abe had stopped dead on the path.

‘Lillie?’ he asked quietly, ‘Was the name Lillie?’

I told him I believed it was. A change came across his face, darkening with a memory.

‘That man is a devil,’ Muir told me. ‘He tracked the Wylers for six months, clear ‘cross the Rockies, before they finally gave up an’ stopped running. I shall not tell you what he did to them.’

He fumbled for his flask and took a gulp of water.

‘Jameson was right, work such as his don’t come cheap. Broke place like Carson City couldn’t afford him. Someone else is after us.’

A creeping certainty ca. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...