- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

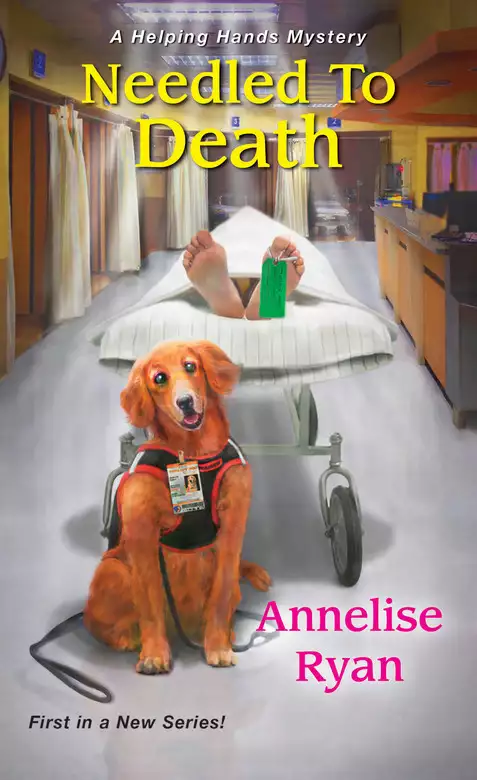

As a colleague of deputy coroner Mattie Winston, social worker Clothilde "Hildy" Schneider is no stranger to unsolved murders at Sorenson General Hospital. Except this time, it's up to her to crack the case....

Motivated by her own difficult past, Hildy has an unparalleled commitment to supporting troubled clients through grief and addiction in Sorenson, Wisconsin. But when a distraught group therapy member reveals disturbing details about her late son's potential murder, Hildy goes from dedicated mental health professional to in-over-her-head amateur sleuth....

Alongside her loyal therapy Golden Retriever, Hildy stumbles through incriminating clues - and an unlikely partnership with Detective Bob Richmond, the irresistibly headstrong cop who shares her passion for helping others. With signs of foul play surfacing all over town, can Hildy and Detective Richmond pinpoint the deadly traits of a sharp-witted killer before another seat gets filled at grief therapy?

Release date: July 30, 2019

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 344

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Needled to Death

Annelise Ryan

Some people wear their cloak of grief for a long time. Others shrug it off in good time and good order, eager and able to get on with their lives, even if it’s only a few small steps at a time. The people who are with me tonight tend more toward the former group, and it’s my job to try to help them become members of the latter group.

I’m about to start the session when a new face enters the room—a woman who looks to be in her mid-to-late forties—and I’m tempted to clap my hands with delight. This would be both inappropriate and unprofessional, so I quickly rein in the impulse and focus on forming a smile that looks warm and welcoming, and hopefully doesn’t show the excitement I feel. I hurry over to her, aware of the curious stares coming from the others in the room.

“Hello,” I say. “Are you here for the bereavement group?” The question is rhetorical, since this woman is wearing her mantle of grief like a heavy shawl. Her face is expressionless, her shoulders are slumped, and her movements are sluggish and zombielike. She looks down at me—nearly everyone I meet looks down at me in the strictly physical sense, since I’m barely five feet tall—and nods mechanically.

“Well, welcome,” I tell her, touching her arm with my hand. “I’m Hildy Schneider. I’m a social worker here at the hospital, and I run this group.”

She nods again but says nothing. I suspect her loss is a recent one, very recent. Who was it? I wonder. Based on her age, a parent is a good guess if one assumes the natural order of things. But I’ve learned that death doesn’t care much for order.

“What’s your name?” I ask, hoping to ease her out of the frozen, deer-in-the-headlights stance she currently has. She looks at me, but I get a strong sense that she doesn’t see me. I’ve encountered this before and suspect she’s mentally viewing some memory reel as it plays repeatedly. I tighten my touch on her arm slightly, hoping the physical connection will ground her. It does.

She blinks several times, flashes an awkward, pained attempt at a smile, and says, “Sorry. I’m Sharon Cochran.” Her voice is mechanical, rote, with no lilt or feeling behind it.

“I’m glad you’re here, Sharon,” I say. “Can I get you something to drink? A water, or some coffee?”

She looks at me with brown eyes that are stone-cold and dull, and then shakes her head.

“There are some cookies, too,” I say. “Can I get you one?”

Again, she shakes her head, her gaze drifting away from mine. The others in the room have lowered the tenor of their conversations to soft, whispered murmurs, no doubt so the newcomer won’t hear them talking about her.

“Sharon?” I say firmly, wanting to bring her attention back to me. “Have you ever been to a support group before?”

“No.”

“Okay. Let me give you a brief overview of how the group works. We meet every week on Thursday evenings unless there is a holiday that falls on that day. In that case, we often meet the evening before. Attendance is totally voluntary. Come as little or as often as you want and come as many times and for as long as you want. Typically, I pick a topic for us to focus on each week, and I talk a little about that topic before opening things up to the group.” She is looking down at the purse she is clutching, fidgeting with its clasp, making it hard for me to tell if she’s hearing me or not. I continue anyway.

“The members of the group have the option of discussing something relative to their individual grief issues and experiences, and if it happens to be related to the topic at hand, that’s great. But it doesn’t have to be. Anyone who wants to talk may do so, but there is also no obligation to do so. The others who are here tonight have all been coming for some time, and they do plenty of talking. You might feel like an outsider because of that, but I promise you that if you commit the time and effort to attending several sessions, that will dissipate. It’s a very friendly and supportive group of people, and all of them share one thing in common with you. They’ve all lost someone close to them.”

She looks at me then, and I see the first spark of life in those mud brown eyes. “How?” she asks.

I’m confused by the question. “How what?”

“How did the others die?”

“Oh. Well, there’s a mix. And rather than my trying to give you any background on the others, I think it will work better if you let them tell you their stories.” I again ponder who it is Sharon has lost. Maybe it was a spouse?

“Any suicides?” she asks. Her eyes are scanning the others in the room.

“Yes,” I say. “Did you lose someone to suicide?”

She nods slowly, frowning and surveying the other attendees.

“There is someone here who lost her husband to suicide,” I say. “She hasn’t had anyone else who shares her situation up until now. I can introduce you to her, if you like.”

“No.” Flat, dead, robotic. “What about homicide?” she says, eyes still roving, though I get the sense that she isn’t focusing on anything or anyone.

“What about it?” I reply, unsure where she’s going.

“Has anyone here lost someone to murder?”

“No.” Something in the back of my brain connects with something in my gut, and instinct makes me qualify my answer. “Well, none of the group members have lost anyone to murder,” I clarify, “but I have. My mother was murdered when I was little.”

I see a spark of interest soften her face, and she looks me in the eye for the first time. “Did they catch who did it?” she asks, which strikes me as an odd thing to ask before expressing some token condolence or inquiring about the circumstances. Though most people merely make an awkward attempt at changing the subject whenever I bring it up.

“No, they never did,” I tell her, feeling a familiar ache at the thought. I glance at the clock on the wall and see that it reads two minutes past seven. “I need to get things started,” I say. “But I’d like to talk with you some more after the group ends, if you can stay for a bit.”

“Sure,” she says, and she gifts me with a tentative smile.

I give her shoulder a reassuring squeeze and then address the room at large, speaking loudly. “Okay, everyone, let’s get started.”

This command is typically followed by one last dash to the snack table to get another cookie, or to top off a cup of coffee. Generally, I allow a minute or so for people to heed my request, and then I start regardless of what’s going on or who might be still hovering over the cookies. Tonight, however, the presence of a newcomer has intrigued everyone enough that things get changed up. The music of the various conversations stops as if on cue and everyone quickly claims a seat as if we are playing a game of musical chairs. I suspect they are eager to rubberneck on someone else’s misery for a change.

The dynamics always change when someone new joins a group. Most of the time it’s a good thing, if knowing that someone is struggling with grief can ever be considered a good thing. I’ve been spearheading this group for nearly two years now, and its composition and size has ebbed and flowed, fluctuating with some regularity. This is good because when all the players stay the same, things can get stagnant. A little fresh blood always invigorates the group.

I’ve had people who came only once, some who came for a handful of sessions, and two regulars who have been here since the group’s inception. The average stay is about ten to twelve weeks for most. Some come alone, others with friends or relatives. The size of the group varies, too, having reached twenty-two people at its peak, though for the past two months it’s been a core group of nine. We are in Wisconsin, so in the winter months the weather sometimes forces cancellations or keeps the group smaller. Now that it’s springtime, I’ve been hoping the group would see some new blood.

I always arrange the chairs in a circle, and while this configuration is designed to create a feeling of community and equality, people tend to form smaller niches within the larger circle, mini groups where they feel the most comfortable.

My two die-hard attendees (though I should probably try to come up with a less offensive descriptor, under the circumstances), the ones who have been coming since I started the group, are Charlie Matheson and Betty Cronk.

Charlie is in his fifties, a widower, with a full head of gray hair that typically stands like a rooster comb by the end of a session, thanks to his habit of running his hands through it. Charlie works here at the hospital in the maintenance department and fancies himself as some sort of soothsayer or prognosticator. He swears he can “read” people and predict their futures after chatting with them for a few minutes. While I don’t deny that the man has accurately predicted the behaviors of some of the group members in the past, it has less to do with any special powers he has than it does his ability to recognize when he has annoyed someone to the point of action. It didn’t take a wizard to figure out that Hailey Crane, a teenager who came to the group with her mother when her father died, would decide to leave the group after one session as Charlie predicted. The fact that, despite my attempts to rein him in, Charlie badgered the girl a couple of times to “open up” and “express yourself” when she clearly didn’t want to be there helped with that prediction.

I had a stern talk with Charlie after that, and I’ve had to do so on other occasions as well, since his actions often necessitate a cease-and-desist warning. If I let him, Charlie would take over the group. I’ve come to realize that he sees himself as my assistant, a coleader or facilitator of sorts, a perception I try hard to extinguish every week. I should probably ban him from the group, but he has a reputation around the hospital of being something of a tattletale. Whenever someone does something he doesn’t like he’s quick to run to the human resources department and file a complaint. He knows how to play the system and isn’t afraid to do so.

Since I can’t steer clear of Charlie, I do my best to control him instead. I don’t want to be on Charlie’s bad side, so I struggle to balance my occasional desire to kill or maim him with my best professional façade. I don’t have the luxury of picking and choosing my clients or patients in this hospital setting, and it’s a simple fact of my professional life that I won’t like some of them, and some of them won’t like me.

Betty, my other long-term attendee, is a widow in her fifties, a stern, hard woman with a sharp-edged face, a tall, lean body, and a no-nonsense attitude. She wears her hair in a tight bun and dresses in drab, sack-like dresses, holey cardigans, heavy stockings, and utilitarian shoes. Betty’s husband, Ned, was a quintessential Caspar Milquetoast kind of guy who not only let his wife lead him around by the nose but seemed to like it. Theirs was a match made in heaven, but when heaven came calling for Ned, Betty found she didn’t know what to do with her bossy personality. She and Ned never had any children—Just as well, I think, as I imagine little Bettys running around like creepy Addams Family Wednesdays—and not surprisingly, Betty doesn’t have many friends. She came to the grief group because she felt befuddled and confused, a rudderless ship adrift on a foreign sea. And she found the perfect home for her acerbic style.

Unfortunately for me, her style is often at odds with what my group is about, and like Charlie, she can be a disruptive influence. The two of them keep me on my toes, I’ll give them that. Tonight, with a newcomer in the mix, I know I will need to be extra vigilant and stay on top of them both lest things get out of control. They’re like sharks smelling fresh blood in the water.

Charlie and Betty don’t like each other, and they often seat themselves on either side of me—a subtle way, I suspect, of declaring their perceived leadership status. This works in my favor, however, because it’s much easier to shut them up if they are within a hand’s reach.

Charlie swears I once pinched him hard enough to leave a bruise on his thigh, a mark he offered to show me after everyone else had left for the night.

“Charlie, that would be completely inappropriate!” I chastised as he started to undo his pants.

He paused in undoing his belt and blinked at me several times. Then he smiled and refastened the belt. “Yes, I suppose it would be,” he said with a shrug and a smile.

After that incident, I kept expecting a call from human resources, but it never came. Charlie was on his best behavior for a few weeks, though Betty stepped in to make sure my duties as group leader remained challenging. While she tends to ignore the women in the group, she has this seemingly uncontrollable need to harangue the men who come, muttering comments like “Man up, you big sissy” or “Warning, man cry ahead.”

Betty would have made a great drill sergeant.

I steer Sharon to a chair and then settle in beside her, earning myself angry stares from both Betty and Charlie, who are seated in their usual places. I tend to sit in the same seat each week, and clearly neither of them anticipated me doing anything different tonight, since they are situated on either side of that chair. I resist the urge to smile, because I have to admit, I enjoy rattling them a bit. It’s good not to let them get too complacent.

“Welcome to this week’s meeting of our bereavement support group,” I begin. “I want to start by reviewing the ground rules first, both as a refresher for those of you who have been here before and to inform our new visitor.”

Predictably, most of those who have been coming for a while roll their eyes or shift impatiently in their seats. But reciting the ground rules is a must.

“First and foremost, remember that anything said in this room is confidential and is not to be discussed or relayed to anyone outside of the group. Remember that we are here to share experiences, not advice. Be respectful and sensitive to one another by silencing your cell phones, avoiding side conversations, and listening to others without passing judgment. And finally, try to refrain from using offensive language.”

I pause and scan the faces in the group. “Any questions about the rules?”

I’m answered with a sea of shaking heads and murmured declinations.

“Okay then. Since we have someone new here tonight, let’s start by going around the group and stating your name and who it is you’ve lost.” I turn and smile at Sharon Cochran. “Sharon, would you like to start?”

I’m pleased when she nods, even though it’s an almost spastic motion. My pleasure then dissipates as she completely derails the evening’s agenda.

“My name is Sharon Cochran, and I’m here because the cops think my son took his own life two weeks ago. But I know he was murdered and I’m hoping you can help me find his killer.”

I often practice and rehearse my responses. It’s an admission I don’t make lightly, because I want people to view my words as spontaneous and sincere, not canned and practiced. But to avoid being caught off guard, I sometimes role-play with myself, trying to anticipate different comments or actions people may make or take, and then practicing my responses to them. I even watch myself in the mirror as I speak, trying to make sure my pale blond hair and narrow face don’t resemble what one coworker once called “a talking Q-tip.”

Unfortunately, Sharon Cochran’s announcement is nowhere in my repertoire of anticipated comments. And judging from the stunned quiet in the room, no one else knows how to respond, either. Finally, Charlie breaks the silence.

“I knew it, you know,” he says. “The minute you walked in here I knew there was something mysterious about you.”

I frown at Charlie, and I’m about to say something to try to mitigate the awkwardness, when Sharon Cochran continues.

“You’re all looking at me like I’m crazy,” she says, fighting back tears. “That’s how the cops looked at me, too. But I’m not. I know my son. They said he died of a heroin overdose, and technically that’s true, but I don’t believe he administered it himself. He didn’t use drugs.”

There are looks of skepticism, sympathy, and curiosity on the faces of the others.

“Okay, he used pot on occasion,” Sharon says with a hint of impatient irritability in her voice. “But what college kid doesn’t these days? And I’m telling you he didn’t use anything else. He had no tracks on his arms, but the cops said that was because it was likely his first time shooting it up, that he’d probably been snorting it before. They think he either killed himself on purpose, or he was unlucky and got too large a dose on his first try. They said there was some really strong stuff out on the streets at the time, way more potent than the usual.”

I’m momentarily at a loss for words, unsure what to make of Sharon’s claims. Denial is a common phase of grief, and not just denial of the death itself. The loved ones of those who die from drug or alcohol abuse often claim someone else is to blame as they struggle to deal with their own guilt for not having done something to stop it. Was that the case with Sharon?

I also know that teenagers and young adults are quite adept at hiding secrets from their parents, and that only strengthens the denial later when things go terribly wrong. I know this not only from my training and experience working with people in that age group, but also because I was quite adept myself at hiding things from the adults in control of my life when I was that age.

In my case, those adults kept changing, which sometimes made the deceptions easier, and sometimes didn’t. My own mother died—was murdered—when I was seven, and I never knew my father. I don’t know if my mother knew who my father was, either, though I have reason to believe she might have had an idea on the matter. But things were complicated. She was what polite company refers to as a “lady of the night,” forced into selling herself to support the two of us.

My mother got pregnant at sixteen, and her very religious, very strict Iowan farm parents disowned her. She ventured out into the world to try and make it on her own, and several months later, that first pregnancy ended up a stillborn. She tried to establish some sort of life on her own since her parents were still stubbornly refusing to let her come home, and two years, several low-paying jobs, and a lot of male customers later, she ended up pregnant with me.

She did her best by me, though heaven knows it wasn’t much, and despite our situation I have some fond memories of her. Her death saddened me deeply and altered my life in ways I didn’t always understand. It forced me into the foster system, beginning a long procession of parental influences, some good, most not so much.

I shake off thoughts of my own mother and refocus. I decide to give Sharon a gentle dose of reality. “What makes you think your son was murdered?” I ask. “What I mean is, why would someone want to kill him?”

“There was something going on at his school,” Sharon says. “I don’t know the details, but something happened that had Toby very upset. He ended up leaving his fraternity over it, and moving home. I tried to get him to talk to me about it, but he wouldn’t.”

“What year was he?” I ask.

“Freshman,” Sharon says. Her eyes well up and she adds, “He had his whole life ahead of him.”

The others in the group are riveted, clearly intrigued by Sharon’s tale. The current mix of people in the group is a vociferous one, and one of my biggest challenges at each session is in getting them to talk one at a time. Yet now they are all silent.

“Sharon, I’m sorry this happened to your son,” I say, hoping to get things back on track. “If you feel strongly that the police have it wrong, then maybe you should take your concerns to them and push the issue. But for here and now, with this group, our focus is on helping you to deal with your grief.”

“Now, hold on,” says Mary Martin, a sixty-two-year-old widow who has been coming to the group for the past four months, ever since her husband died of cancer. “We can’t just dismiss her claims. What if she’s right? What if her boy was murdered?”

“Yeah,” pipes up Bill Nolan, a forty-something gay man who lost his partner to an automobile accident two months ago and has been attending the group since then. “Why can’t we help her?”

He sounds as eager as Mary, and when I see the others in the circle nod in agreement—everyone except for Betty Cronk, who looks bored—I realize what’s going on. The group has seized upon the mystery of Sharon’s son’s death as a distraction, something to take their minds off the typical grief therapy issues they normally focus on. While this isn’t necessarily a bad thing—in fact, it could prove to be a therapeutic diversion if handled correctly—I don’t want the focus of the group to shift away from its main purpose.

“I’ll tell you what,” I say to the group. “We’ll let Sharon tell us what she knows, assuming there is anything more she has to share on the matter, and we’ll focus on the details of that toward the end of the hour. But for now, I want us to stay focused on tonight’s topic. Let’s give the first half of the hour over to the topic at hand, and then we can shift later. Okay?”

Judging from the looks I’m getting, it’s not okay. I understand their curiosity; I share it. A potential murder mystery is great fodder for keeping one’s mind off other, more painful things, and it can give one a sense of purpose and direction. I’ve done some investigating into my mother’s death, feeling the need to avenge her and bring her killer to justice. But her case is more than twenty-five years old—not just a cold case but a frigid one—and I’ve made only minimal progress.

As I read the facial and body language of my group—scowling expressions, arms folded over chests, bodies shifting anxiously in seats, heads turned dismissively away from me—I decide to go off the reservation, a term that Carla, one of my fellow foster sibs, used years ago whenever she was going to do something unexpected, which, as it turned out, was often. Carla was fun but a bad influence on me.

“How about we open it up to a vote with a show of hands?” I say. “Who wants to focus solely on Sharon’s son’s death and the circumstances surrounding it?”

Every hand in the circle goes up except Betty’s. The others all turn to look at her and I debate whether or not the vote should be a unanimous one. If even one person doesn’t want to stray from the program, am I doing that person a disservice by giving in to the whims and wishes of the others?

The dilemma resolves itself seconds later when Betty arches one eyebrow, mutters an irritated “Fine,” and raises her hand. If it wasn’t for the hint of a smile I see at the corners of her mouth, I’d be worried. But I suspect Betty is just as interested in this course of action as the others are. She just doesn’t want to let on to the fact. It doesn’t fit in with the reserved, in-control persona she’s established here.

“Okay, then,” I say, adding the caveat, “but only for this session.”

The transformation on the faces in the group is startling and I worry that I’ve opened a dangerous can of worms here. “Sharon, do you feel comfortable giving us some more details about your son’s death and the events that led up to it?” I say.

“Do I feel comfortable?” she says with a scoffing laugh. “I’m delighted about it. I’ve been trying to get someone, anyone, to listen to me ever since it happened. I know people think it’s just some form of denial on my part, that I’m fixated on this as a way of avoiding the pain of it all. But that’s not it.”

“Then go ahead,” I tell her. “But if at any point it begins to feel uncomfortable for you, feel free to stop. You are under no obligation to talk, okay?” Though I mean this, the hungry, eager expressions on the faces of the others make me think they’d try to force her to continue whether she wanted to or not.

“Okay,” Sharon says in an oddly chipper tone.

“The usual ground rules still apply,” I tell the others. “If this thing gets out of hand in any way, I’m going to call a halt to it, understood?”

Enthusiastic nods and murmured assents answer my question. While I still think Sharon’s focus on this aspect of her son’s death is, in all probability, a way to avoid, escape, and defer, I can’t see the harm in letting the others shift their focus from their individual losses. At least for tonight.

It certainly isn’t by the book, and I’m not sure other social workers or group managers would approve, but I’m willing to experiment a little. I’ve always liked thinking and doing things a little outside the box. Sometimes a lot outside the box. The fact that it’s gotten me into trouble on more than one occasion in the past is a thought I gently push aside.

I just hope my boss is as open-minded on the subject as I am.

It turns out Sharon Cochran is a born storyteller. She has a clear knack for organizing her thoughts and the necessary details, relaying them in an orderly and understandable fashion, and doing it all with just the right amount of inflection and emphasis on her words. As I listen with rapt attention to her story, I make a mental note to ask her later what she does for a living.

“Toby belonged to a fraternity on the UW-Madison campus,” she says. “He pledged them and went through their hazing ritual, something he refused to tell me about. Everything seemed great for several months. Toby was getting good grades, and he sounded happy whenever I spoke to him. When he came home for Christmas break he was excited about switching his major. Originally, he planned on studying information technology and getting a teaching certificate, but suddenly, he had this big interest in computer program. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...