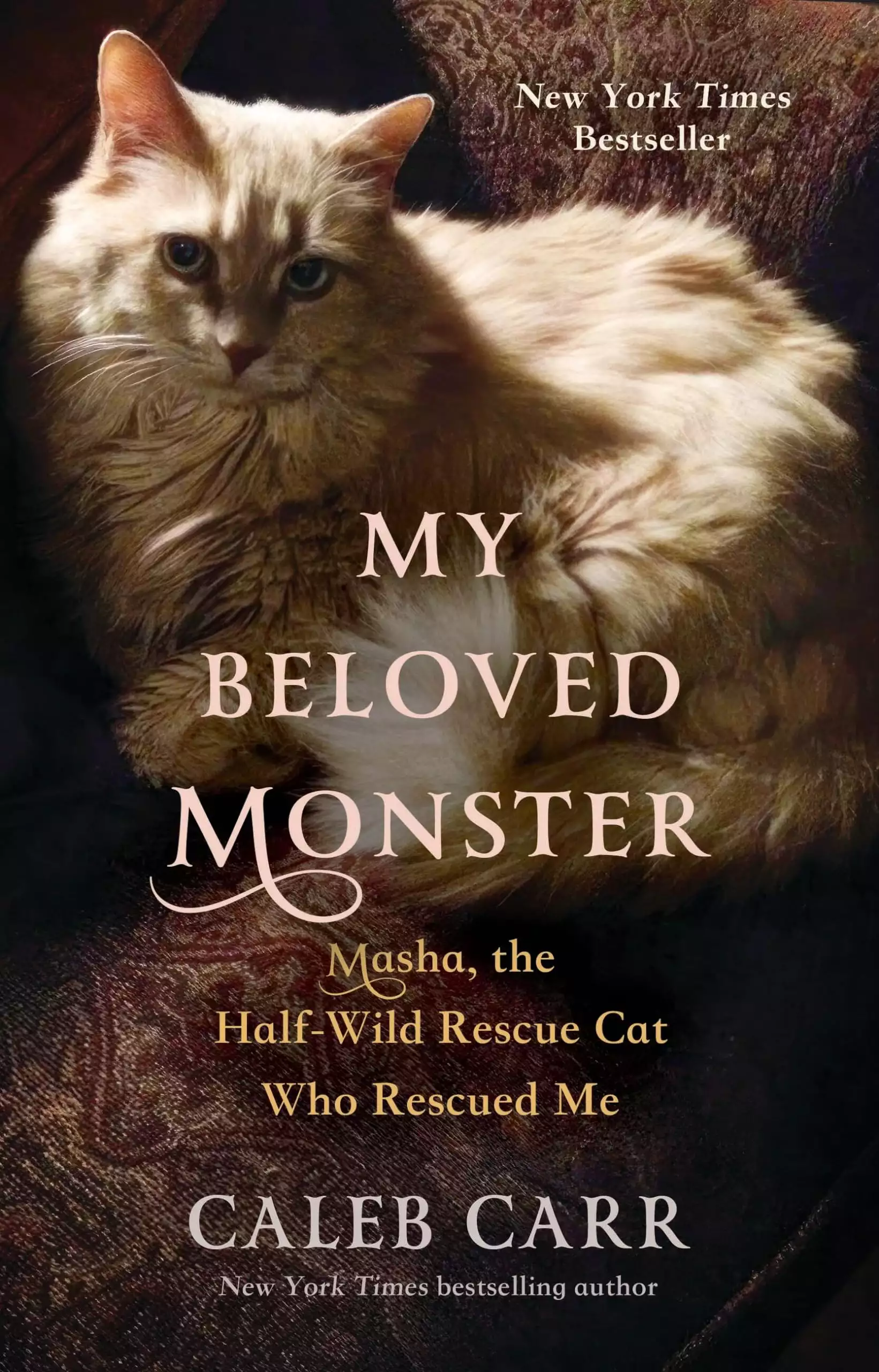

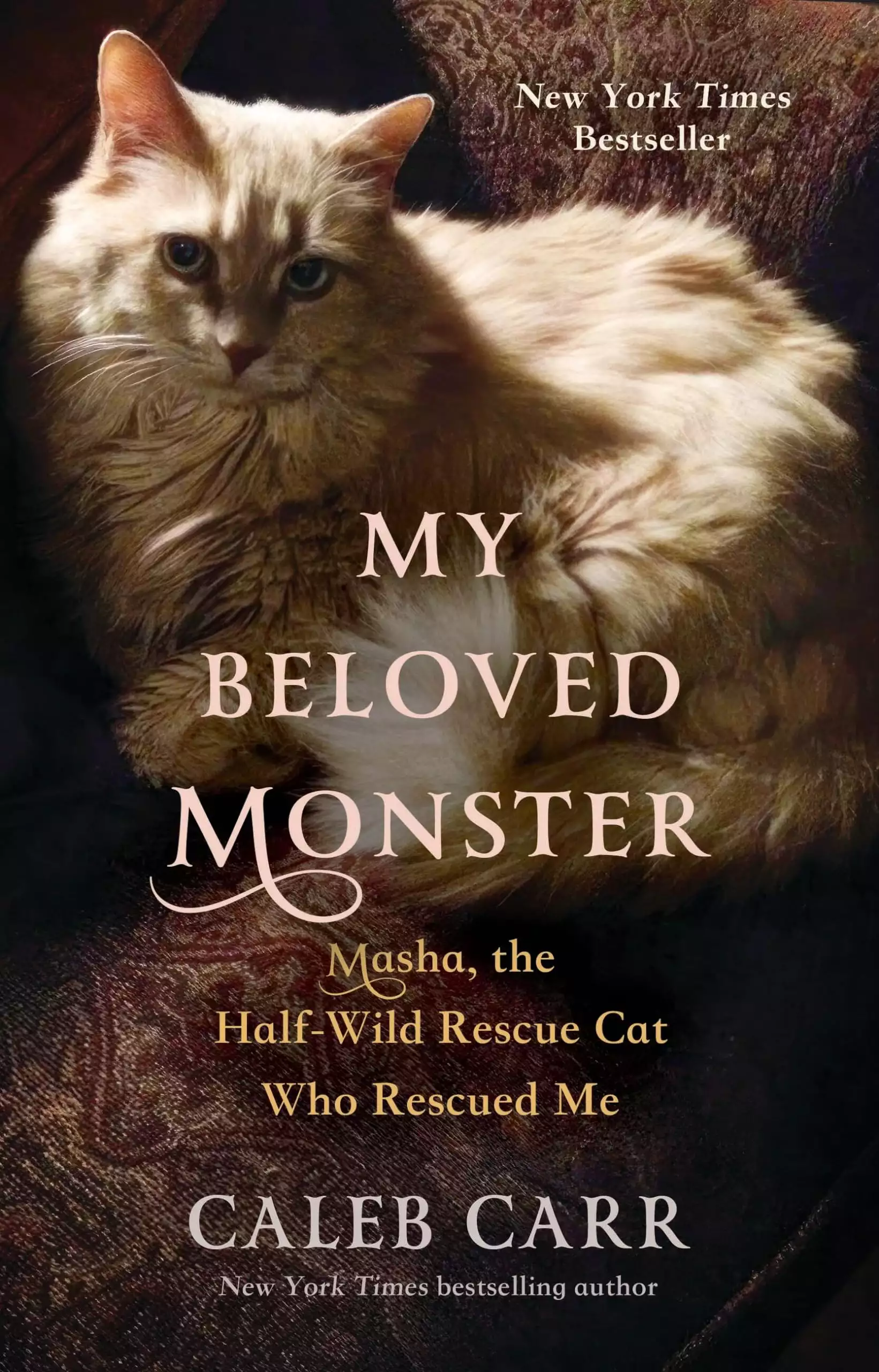

My Beloved Monster: Masha, the Half-wild Rescue Cat Who Rescued Me

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

AN INSTANT NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

“The most brilliant feline portrait in literary history.” –People Magazine (Book of the Week)

The #1 bestselling author of The Alienist tells the extraordinary story of Masha, a half-wild rescue cat who fought off a bear, tackled Caleb like a linebacker—and bonded with him as tightly as any cat and human possibly can.

“Dares us to take a journey into love and pain . . . My Beloved Monster is a love story and a requiem.” –Wall Street Journal

“Excellent…Worth the emotional investment, and the tissues you will need by the end, to spend time with a writer and cat duo as extraordinary as Masha and Carr.” —Washington Post Book World

Caleb Carr has had special relationships with cats since he was a young boy in a turbulent household, famously peopled by the founding members of the Beat Generation, where his steadiest companions were the adopted cats that lived with him both in the city and the country. As an adult, he has had many close feline companions, with relationships that have outlasted most of his human ones. But only after building a three-story home in rural, upstate New York did he enter into the most extraordinary of all of his cat pairings: Masha, a Siberian Forest cat who had been abandoned as a kitten, and was languishing in a shelter when Caleb met her. She had hissed and fought off all previous carers and potential adopters, but somehow, she chose Caleb as her savior.For the seventeen years that followed, Caleb and Masha were inseparable. Masha ruled the house and the extensive, dangerous surrounding fields and forests. When she was hurt, only Caleb could help her. When he suffered long-standing physical ailments, Masha knew what to do. Caleb’s life-long study of the literature of cat behavior, and his years of experience with previous cats, helped him decode much of Masha’s inner life. But their bond went far beyond academic studies and experience. The story of Caleb and Masha is an inspiring and life-affirming relationship for readers of all backgrounds and interests—a love story like no other.

Release date: April 16, 2024

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 341

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

My Beloved Monster: Masha, the Half-wild Rescue Cat Who Rescued Me

Caleb Carr

During those years, the days and weeks began to matter much less to me than did the phases of the Moon, the winds, and the seasons. Once, I might have noted that such a long span could have contained an appreciable marriage, or the bulk of a career, or a child’s development from birth to high school graduation. But those kinds of milestones, never very important to me, shrank to complete insignificance while we lived together in the house that steadily became, from the instant she entered it, more hers than it was mine. Increasingly, my sense of time became her sense of time, and her sense of time was governed by sunlight and darkness, the sounds of the prevailing winds shifting from mild to roaring over the chimney, and the changing shape of the glowing, arcing disc in the night sky, which she sat and watched from her various outdoor and indoor reconnaissance posts. We filled each day—and even more, given our shared habits, each night—with the business of those hours: writing for me, hunting and defending our territory for her, and sleeping as well as sustenance for us both. But any larger, external sense of life moving on was, ultimately, ruled by the seasons.

Yet there were internal and alarming signs of life’s passage, too: we both had injuries and illnesses and the simple perniciousness of age to remind us that the years were mounting up, that we weren’t as strong or as fast, or as quick or resilient, as we’d been at the start. But neither of us ever stopped fighting against such attempted intrusions into our long-established routines. And ultimately what mattered most was not the maladies and the hurts but the fact that we were there for each other, always and at every possible moment, during and after them. For as long as was needed, time was suspended; and only when each crisis passed would the primacy of the great unseen clock that divided light from darkness, heat from cold, bare branches from lush vegetation, be acknowledged again.

We were, then, ourselves timepieces: both of us recognized this quality in our respective souls and bodies, of course, but we also caught it, perhaps more pointedly, in each other’s. Injuries and illnesses from which we recovered less and less rapidly until every one left traces and then changes that were no longer disguisable, no longer subtle at all: these were the inescapable marks of time, as were the limitations they represented, and they could only be ignored up to a steadily more constricted point. It was in both our natures to keep trying to push past the constrictions, often dangerously, and always to each other’s dismay. But we did it anyway, both knowing that when we fell short of any given objective, we would not be alone. Perhaps we were even testing that consolation, just to be sure of its permanence. After all, the sometimes-agonizing pain resulting from those reckless attempts was, with only a few exceptions, never so great as was the comfort of each other’s company during convalescence. And that was one more thing that kept me, and I suspect her, from even imagining a day when the pain would have no remedy or consolation at all.

Seventeen years; and here we are at that day. The one of us in spirit, the other in scarred, aging body with just one risky job, the last risky job, left to do: to tell the story of the shared existence that filled those years. For, after all, they were years that formed—whatever our method of measuring them—a lifetime; a lifetime that cannot help but remain vivid in my memory. It was Masha’s lifetime: Masha, the name that she chose for herself during our very first meeting. Yes, she was a cat; but if you are tempted, even for an instant, to use any such phrase as “just a cat,” I can only hope that you will read on, and discover how that “mere” cat not only ruled her untamed world, but brought life-affirming purpose to my own.

In the face of such claims, a question persists: “But how could you live for such a long time, alone on a mountain with just a cat?” It’s sometimes asked prejudicially, by people who, if queried in reply as to whether they would be as amazed if I said I had been living with a dog, or even a horse, nod and opine that they could imagine that scenario—but a cat? Such people are usually beyond any ability to really process explanations; but to those who aren’t, I can only say that the experience of being a person alone with a cat for so long and in such wild country depends to some extent on the person, but far, far more on the individual cat. And in Masha was embodied a very rare animal indeed: a cat who expanded the limits of courage, caring, and sacrifice. Think that’s beyond a cat? Think again.

There are aspects of her story that you may consider embellished; but I can assure you that they are all perfectly true. Hers was the kind of life that most cats—locked away in little apartments and houses, often with the best of human intentions, yet with the unchangeably wild parts of their souls nonetheless inhibited, and no outdoor domains to rule—can only experience in dim flashes, as if envisioning a glorious if perilous past incarnation. The kind of life, in short, that most cats can only dream of…

Masha lived it.

The drive north those seventeen years ago actually took little more than an hour and a half; but it seemed longer, a false impression created whenever I found myself driving through Vermont. It’s a state about which many New Yorkers, myself included, tend to feel a bit ambivalent, not least because Vermonters (or “Vermunsters,” as New Yorkers often have it) can sometimes be a self-satisfied if not downright smug and even hostile lot, who consider themselves more “organic,” more closely tied to and respectful of the land, than are their countrymen next door. A friend of mine from their largest city of Burlington, for example, once told me that Vermonters view the difference between New Yorkers and themselves as “the difference between fleece and wool”: exactly the kind of fatuous crack that can (and did) elicit a creative volley of obscenities from denizens of the Empire State.

Regional animosities aside, however, there were more immediate grounds for my uneasiness that autumn day. As it happened, animal shelters in much of northeastern America had for some months been plagued by a particularly virulent and deadly form of kennel disease; and if you were thinking about adopting an animal, which I was, you had to make absolutely sure that you went to a shelter known to be clean and uninfected, like the one outside Rutland, Vermont, toward which I was headed. It had been okayed by my then-veterinarian, and this was not an excess of caution: one of the most insidious things about this disease was that, like many kennel plagues, it wasn’t just transmitted by cats and dogs to one another in shelters and breeding mills: people, having visited an infected place, could bring the illness out and transmit it to animals in other places by carrying it on their skin, clothes, and hair. The consequences of such carelessness could be extreme, as I’d recently learned through a visit to an unsafe location: when I told my then-vet that I’d visited the place and even touched one animal, he ordered me to go straight home, take a very hot shower for at least half an hour, and burn—yes, burn—the clothes I’d been wearing. Then I would have to wait a minimum of two weeks before visiting any approved shelters, to make doubly sure I wasn’t carrying the illness.

At this, I’d uttered a quiet, saddened version of one of those volleys of obscenities to which I’ve mentioned New Yorkers being partial. I’d finally gotten ready, even anxious, to adopt another cat, and it’d taken long months of mourning for me to reach that point: my last companion, Suki, had, after four years of unexpected but very close cohabitation, been claimed by the cruelly short life expectancy (just four to five years) of indoor-outdoor felines, especially those in wildernesses as remote as the one we inhabited. In fact, before encountering me and deciding that I was a human she could trust, Suki had lived on her own for two years and raised at least one litter of kittens in the wild, and so had beaten the odds admirably; but her disappearance had nonetheless been a terrible blow, and, as I say, it’d taken a lot for me to get to where I could think about bringing someone new into my world. The prospect of waiting another two weeks once I’d made up my mind was therefore mightily disappointing; but it was my own stupid fault and I had to accept it.

Winter rarely comes late in the Taconic Mountains; and with autumn reminding me again of this fact, and my having recently moved from a small derelict cottage into a ridiculously oversized new house that I’d very nearly bankrupted myself building, I began to feel that renewed companionship was not only desirable but necessary. After all, when you live at the foot of a particularly severe mountain called Misery that is riddled with bear dens, coyote packs, bloodthirsty giant weasels called fishers, and various other predatory

fauna, it’s all too easy to sense how “red in tooth and claw” Nature can really be—especially when the temperature hits thirty below and the snow starts coming in three-foot installments. On top of all that, I was already dealing with several chronic health problems that had long since led me to live a solitary life, so far as my fellow humans were concerned. Taken as a whole, these factors were pushing that tooth-and-claw sensation over the line and into dread, and the importance of having another living thing with whom to share those long, looming months was mounting.

So I quickly began to scan online photos of available cats at acceptable shelters. You can never go by appearance alone, of course, when it comes to animal adoption: personal chemistry between adopter and adoptee is far more vital, something that helps (but does not solely) explain the failures of so many adoptions during the Covid-19 pandemic, when pre-adoption visits were largely forbidden. And it’s not just one-way: whatever your own feelings regarding any possible cohabitant, you have to give that animal the chance and the right to decide if you’re the correct person for her or him. (If it seems odd that I don’t use the word “pet,” I can only say that I’ve always found it a diminutive behind which lurk a thousand forms of abuse.) So far as mere photos went, however, Rutland did seem to have some likely candidates; and since my vet had given it the okay, I decided to call and set up a visit.

And then, the first hint that something unusual was up: I was told that in fact they had more cats on hand than were pictured on their website, though when I asked why, the voice at the other end became evasive. It wasn’t the kennel disease, a plainly distracted attendant assured me when I asked; but as far as candidates for adoption went, well, it would probably be best if I just came up and had a look.

The idea that this was more perfidious Vermunster-ing did cross my mind; but I tried to stifle such provincial feelings as I headed north. And, overall, by the time I’d covered half the distance to the shelter I had overcome most of my uneasiness and felt ready to meet whatever awaited me.

I was, in a word, not.

The Rutland County Humane Society, like most such institutions, is located not in the city from which the county takes its name but just outside it, in a much smaller community called Pittsford. The structure, too, was not unusual for such facilities: a low, somewhat rambling single-story building of aging-modern vintage, surrounded by dog kennels and other telltale signs. It looked relatively peaceful as I parked, despite the predictable barking of the dogs who were outside at that moment and evidently thought I might be their ticket out of the chain-link. But when I stepped inside, a different atmosphere prevailed: controlled urgency would be the best way to put it, with attendants in full and partial scrubs rushing about and trying to cope with what was apparently

an overload of business.

And that overload was easy to see in the main hallway that led back among offices and exam rooms: cages of every description, all containing cats, were stacked three and four high against one wall. All this was in addition to the animals and habitats in the couple of rooms that housed the usual complement of whiskered ones. I asked a passing attendant what was happening, and got a quick explanation: apparently an elderly recluse, one of those people who give the phrase “cat person” such a pejorative connotation among much of the general public, had been raided a couple of days earlier. The bust had happened for the usual reasons: neighbors reported intolerable smells and sounds coming from the woman’s small house, and when animal control officers gained entrance they found sixty-odd cats struggling to survive in what was supposed to be their home.

Such awful places and the people who create them out of some delusional sense of caring are not uncommon (more’s the human shame), but this case had been extreme by any standards: the first order of business had been to find shelters among which the cats could be distributed, then to wash them, since hygiene in the small house had been nonexistent (urine being so soaked into the floorboards that the wood was spongy), and finally to get them all spayed and neutered. It was an enormous undertaking, one requiring the staff of as many shelters as possible, and the charitable offices of every vet in the area who would help. Things were only now starting to come under control, I was told, so if I wanted to roam around by myself I was welcome to, and someone would be with me as soon as possible.

Absorbing all this information, I began to look at all the mostly terrified, still recovering faces inside the cages. For a moment I speculated on the nature of a human mind so tragically warped that it could create such awful consequences, but the moment was passing: a flash of color from down low caught my eye, and I spun around. Initially I thought I was hallucinating: the color was very close to what Suki’s had been, and I’d always considered her fur unique. Blonde, with almost a halo-like ticking of pure white at the tips of her fur, it had created an arrestingly beautiful, in some lights even ethereal, effect; and here I was seeing it again, or so I thought. I went immediately to the spot.

Down near the floor, trapped in one of the small traveling carriers that make human lives easier but also prevent their occupants from either standing up fully or stretching out completely, was a young cat, unmistakably female (the smaller and more delicate size and shape of the head is the first and quickest way to judge), with two of the most enormous eyes I’d ever seen. She had clearly seen and sensed me before I’d become aware of her, and now she was watching my approach intently, even imploringly. I’d been right, the general color of the fur was like Suki’s, but there were important differences: Suki had been a shorthair, whereas this one’s fur was lengthy, growing in flat layers that avoided too

much of a “puffy” effect. Her tail, however, was unabashedly large and luxuriant in all directions, like a big bottle brush or duster. In addition, where Suki’s eyes had been a brilliant shade of light emerald, this girl’s eyes were remarkable for their deep amber—indeed golden—color, as well as for their enormous size in proportion to her head. They had a round, what is called “walnut” shape (as opposed to the more exotic “almond,” or oval, eyes of many domestic cats), and their pupils were almost completely dilated, despite her being in a well-lit area. Fear or discomfort could have been responsible for this dilation, of course; but she didn’t seem to be either in pain or deeply afraid. It was more like nervousness, an attitude that would have been fully justified by the predicament in which she found herself. Yet as I got nearer, this explanation didn’t seem to fit, either.

Up close, her big, brave stare took on an air of searching insistence, which only made it more expressive. Indeed, it was one of the most communicative gazes I’d ever seen in a cat, a look facilitated by the structure of her face: the eyes were oriented fully forward, like a big cat’s rather than a domestic’s, and seemed to comprehend everything she was studying—especially me—only too well. When she held her face right to the cage door, I could see that her muzzle was frosted white at the nose and chin and oriented downward more than the outward of most mixed breeds, allowing her even greater range of vision. On either side of her head she had tufts of fur extending out and down, like the mane of a lynx or a young lion; and these led to and blended in with an unusually thick and impressive “scruff,” that collar of vestigial extra skin around a cat’s neck that their mothers use to lift them when they are kittens (and that some humans, even some veterinary assistants, mistakenly believe they can grab to control and even lift a grown cat harmlessly, when in fact cats find it uncomfortable and cause, sometimes, for retaliation). Finally, exceptionally long white whiskers descended in two arced, rich clusters from the white of the muzzle, increasing the effect of the kind of active wisdom present in big cats, as did the animated ears, each turning and twisting on its own at every sound.

Taken together, the features were of the type that some people call a “kitten face,” and with reason: the look is unmistakably reminiscent of very young cats. But even more vitally (if less sentimentally), forward orientation of the eyes in adult cats serves the same purpose that it does in their big, wild cousins: more coordinated binocularity (or stereoscopics) improves vision, especially when roaming and stalking at night. Then, too, it should be remembered that

“kittenish” does not imply ignorant or naïve: feline cubs and kittens have one of the steepest learning curves in Nature. From weaning through their earliest weeks they are forever studying and observing their surroundings, along with modeling their elders and experimenting when on their own. This is true even, and often especially, when they seem to be simply playing; and it’s all so they’ll be ready when their mother kicks them out and on their own, which in the wild occurs at only four to five weeks.

Was this cat hunting me, then? That didn’t seem the explanation, though her detection of me before I’d even caught sight of her did indicate an agenda of her own. And there was something very intriguing in that, because of what it exemplified about how cats read, identify, and select human beings.

As I got closer, she continued to put her nose and face up against the thin, crossed bars of the cage urgently, her confidence and her persistence seeming to say that I was right to be intrigued by her, but that my main task right now was to get her out. Smiling at this thought, I leaned down to put my face near hers, but not so near that she couldn’t see me (at very close range—closer than, say, six or eight inches—cats’ eyes lose some of their focus). Then she began to talk, less repeatedly and loudly than the other cats, and more conversationally. I answered her, with both sounds and words, and more importantly held my hand up so that she could get my scent, pleased when she inspected the hand with her nose and found it satisfactory. Then I slowly closed my eyes and reopened them several times: the “slow blink” that cats take as a sign of friendship. She seemed receptive, taking the time to confirm as much with a similar blink. Finally, she imitated the move of my hand by holding one of her rather enormous paws to mine, as if we’d known each other quite a long time: an intimate gesture.

It may seem that I was reading too much into a few simple interactions, especially something so simple as smelling my hand. But things are rarely as simple as they may look or seem, with cats. The question of scent, for instance, is not only as important for cats as it is for dogs, horses, or almost any animal; it is arguably more so: besides being somewhat less efficient up close, cats’ eyes are not at their best in bright light. Their vision truly comes alive at middle to long distances, and especially, of course, in the near-dark (they are technically crepuscular, or most active in the hours just before complete sunset and dawn), all of which contributes to their sometimes “crazed” nighttime activities. When you enter a well-lit room and a cat looks up at you from a distance anxiously, they’re doing so because at that moment you are a general shape that they need to hear from and smell. Our voices are important initial identifiers to nearly all cats, and having further determined who we are by scent, they will relax—or not, depending on their familiarity with us and what our chemical emissions, even if unremarkable to us, say about our intentions.

It’s often thought to be folksy wisdom that cats can detect human attitudes and purposes. Yet they can indeed sense such things as nervousness, hostility, and even illness in what we radiate. On the other hand, if we emit warmth, ease, and trust, they can tell that, too.

But this is not some mystical ability: cats are enormously sensitive to the chemical and especially pheromonal emissions that many other creatures, including people, give off according to their moods and physical states. This uncanny ability developed as part of their predatory detection skills but broadened to include self-preserving appraisals of animals that might be a danger to them. Conducted through not only the nose but also the Jacobson’s, or vomeronasal, organ in and above the palate (which they access by way of the Flehmen response, during which they open and breathe through their mouths in a distinct way that is almost like a snarl by isn’t one), this ability is chemically complex but vital. During both predation and defense and ever since their earliest decision to live among us, it has helped them determine not only what potential prey and dangers are about, but which humans they will and will not trust or feel affinity toward.

Put simply, if you’re a person who finds cats untrustworthy or sinister, then you bring that lack of trust to every encounter with them. You involuntarily exude it, chemically, and no cat will want anything to do with you. Similarly, people who are allergic to cats often justify their dislike of felines by spreading the myth that cats somehow conjure a dysfunction in the human immune system out of deliberate malice. Rather than someone who can make no secret of such unease, cats will prefer someone who, however fallaciously, at least believes they are a friend to felines—like the woman in Rutland whose house had been found to contain more than sixty of them. Dogs tend to trust blindly, unless and until abuse teaches them discretion, and sometimes not even then. Cats, conversely, trust conditionally from the start, said condition being that their impression of you—which they take whether you want them to or not, which is beyond human falsification, and which must be periodically renewed—is positive.

It’s this quality that gives cats their apparently scrutinizing and standoffish aspect: they do indeed hold back and size us up until they’re confident of us, a self-defense mechanism that is a facet not only of their anatomy, senses, and natures but of their comparative lack of domestication, as well. Although the exact timing of their arrival in human communities is still being debated, what’s more important about that appearance is that even when their supposed domestication became established, it remained qualified: they were not reliant on us in the same ways other animals were. They entered our lives opportunistically, because our food attracted their prey (primarily rodents and birds) and because they enjoyed rooting through our garbage for edible bits. Being thus independent, they never became responsive to punishment and negative

reinforcement as forms of discipline and training: they didn’t need us, but rather made use of us. Their loyalty depended on mutual respect and decent treatment. And to this day, their characters retain varying but high degrees of this wild element, to which they will revert wholly when given abusive cause (or sometimes simple opportunity): they will disappear into the night, often never to come near humans again.

Certainly, the young cat I was now studying so intently, and vice versa, was busy determining my acceptability in a way that seemed reminiscent of a wild animal—or was she so wild that she had already made up her mind, and was urging me to stop dragging my feet and do the same?

I was about to get some answers. I signaled to the same attendant, then indicated the cage. The woman nodded and smiled a bit—until she saw where I was pointing. Then she glanced around, buttonholed another woman who seemed to be overseeing the activity in the hallway while writing information on a clipboard, and murmured something in her ear. The boss glanced at me, then at the cages, gave a nod of her own (but no smile), and finally turned to the attendant with a shrug, saying something that seemed along the lines of Well, if he wants to see her, let him…

So with careful, apprehensive steps, the woman walked toward me.

CHAPTER TWO“YOU HAVE TO TAKE THAT CAT!”

As the attendant drew close, I could see that her deliberateness was a function not simply of anxiety but of downright fear. “This one right here,” I said, still pointing down at the blonde cat’s cage. “Can I possibly spend a little time with her?”

“Yeah, that one,” the attendant replied dubiously. “Umm…”

I tried to read her look. “Is there a problem? Are you not putting the cats from that house up for adoption yet?”

I was surprised by what came next: “No, no. That one wasn’t involved in the lady’s house. She came from another place—some family left her locked up in their apartment when they moved away. She was there for days, without much food, and what there was ran out fast. We only got to her because the neighbors eventually heard the crying and the—noises…”

“‘Noises’?”

“Yeah. Crashing, bumping—she really wanted out.”

“Understandably,” I said, looking back down at the cat: the enormous eyes seemed even more beseeching now, a quality that inspired ever more sympathy as she kept them locked on me. But pride was still plain, too. I needed a second to absorb what I’d been told. “How could anybody just—leave her, especially trapped like that…?”

“Pretty common, unfortunately,” the attendant answered. “So, yeah, listen, if you want, we have a visiting room where I can bring her, and then you can decide.” She started to shift cages so that she could get the blonde one’s out. “And take your time!” the attendant added: more of a plea than the granting of permission, I thought. And maybe she realized it, too, because she quickly added, “As you can see, we’re pretty busy…” But again, that hadn’t been her actual point, or so it seemed to me: she wanted to give me an unusually long time to decide that I wanted to take the cat—just why, I couldn’t say.

We walked down the hall to a fair-sized room with upholstered chairs and a sofa, along with more carpeted climbing structures that led to beds for the cats. I asked, “When did you bring her in? It can’t have been long ago, she’s too beautiful—somebody must have been interested.”

“Yeah, you’d think—” the attendant started to answer; but then she cut herself off very deliberately. “But she’s been here for… a while.”

Which was puzzling. “Is she any specific breed? She kind of looks it.”

“One of the vets said she’s pretty much pure Siberian.”

Siberian? I’d never even heard of such a breed. But it didn’t seem the time to go into it: still uneasy, the woman led the way into the visiting room and indicated that I should sit on the couch.

“Okay!” she said when I’d taken a seat and she’d set the cage beside me, leaving herself a clear path to the door. “Just let me…”

Glancing back as if to make sure the door was still open, the woman undid the latch on the carrying cage and retraced her steps hurriedly, as if she’d just placed an explosive and it was about to go off. “Like I say, take your time!” she repeated; and then, in a continued rush, she got back into the hallway and closed the door.

All very confusing; but, left alone in the room with the cat, I opened the carrier door fully, and out she came, carefully but bravely, now interested in the room as well as in me. She clearly knew the chamber: it didn’t take long for her to orient herself, and then she turned those big gold-and-black eyes my way. I murmured some greetings, letting her smell my hand again before I tried to pet her; and then, very quickly, she became enormously engaged and engaging, not only allowing me to pet her but leaping onto the

back of the couch so that she could get a more complete impression of me by placing those big forelegs and paws on my head as she chewed at a small clump of hair (a further chemical assessment performed by the Jacobson’s organ). After that she leapt down, bumped or even slammed her forehead into me, and twisted her neck to drill it home, affectionately but forcefully, and finally turned to make her most serious pitch.

She began to run to and leap up on every piece of furniture and each climbing structure in the room, returning to me after each mission as if to demonstrate that she was healthy and ready to go. She even leapt up and bounced, literally, off one wall with her legs, like an acrobat: which, of course, all cats can be. She was particularly fast, and I soon saw why. Her tail was more than simply fluffy; there was an unusually thick appendage under the long fur, and she used it for counterbalance, less like a house cat, it occurred to me, than like a snow leopard (a comparison also suggested, I realized, by the Siberian’s profile, which seemed a miniature version of that same big cat’s features). Cats’ tails are not like dogs’: they are, effectively, a fifth leg, tied directly into the spinal column and the central nervous system and vital to their speed and safety, as they swing it around to counterbalance the quick movements of their bodies. Most so-called domestic cats, though, have thinner tails than this gymnast’s: whatever Siberians were, I thought, they must have been a fairly recent addition to the domestic family.

Assuming they even were domesticated: the golden girl continued to move wildly yet in perfect control, with none of those little gaffes that make the internet come alive. I began to make noises as she dashed about, little whoosh-ing sounds that became louder. Listening to those sounds and to my occasional words of commendation, she correctly identified them as appreciative, and her activity became even more animated. Before long, the whish-ing became shish-ing and then, finally, shash-ing, as I began to search for what sounds she preferred.

This process wasn’t random. During a lifetime with cats, I’d learned something fundamental about naming them: give them enough possibilities, embodying various exaggerated consonant and especially vowel sounds, and they will eventually choose one for themselves by responding to the phonetics. Once they make their choice, they will respond to that name every bit as much as a dog will (whether they will obey the ensuing command, however, is another question). The reason so few cats exemplify this behavior is that humans impose names on them that do not resonate with the cats themselves—names that are, let’s face it, generally far too long and far more absurd and insulting than are dogs’ names. Short, distinctive sounds are the best tickets: for example, my last cat’s name, Suki, had been a formalization of sokay, derived from “it’s okay,” words—and, even more, a very identifiable sound—that I repeated over and over to her whenever she seemed confused or concerned about some aspect of life in her new home, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...