If someone had told me that in this season of my life I would be living in a little ranch house all by myself with just a couple of ornery goats as company, I would have laughed. This life wasn’t the one I’d planned. Growing up in my Amish district as a young girl, I dreamed of love, of a husband, and of children. I’d had two of those, just not for as long as I would have wanted, and the third was not to be. But as the saying goes, “If you never taste the bitter, you won’t know what sweet is.”

Even though I didn’t have children of my own, the Lord saw to it that I would help young people in a different way. He gave me the gift of recognizing love and affection. I knew, knew down to the very center of my bones, when two people were meant to be together. And I knew when they were not. My niece Edith Hochstetler had not yet found that unshakable love. She hadn’t found it with her first husband and I knew, as sure as I knew my dear Kip was waiting for me at heaven’s gate, that she had not found it in Zeke Miller.

I brushed dirt from my garden-glove-covered hands. Having only lived on my little hobby farm for a few months, I was finally in the process of putting my garden in. Planting the flower bed was the perfect way to convince Edith to come over. An avid gardener, she never turned down an opportunity to get her hands in the dirt. This was a characteristic that I was counting on because it was time that she and I had a little chat about her future.

For the garden, I’d collected a number of rocks from my brother’s quarry, and I planned to nestle them in among the plants. My mother always had a rock garden in her home, and so would I. Tradition is important, even more so if you’re Amish. Every season has its own rhythm and duties, from planting to farming to harvest and on and on. Some of my Englisch friends would hate the monotony of it all. Had they been raised Amish, they would find comfort in knowing what was expected of them next.

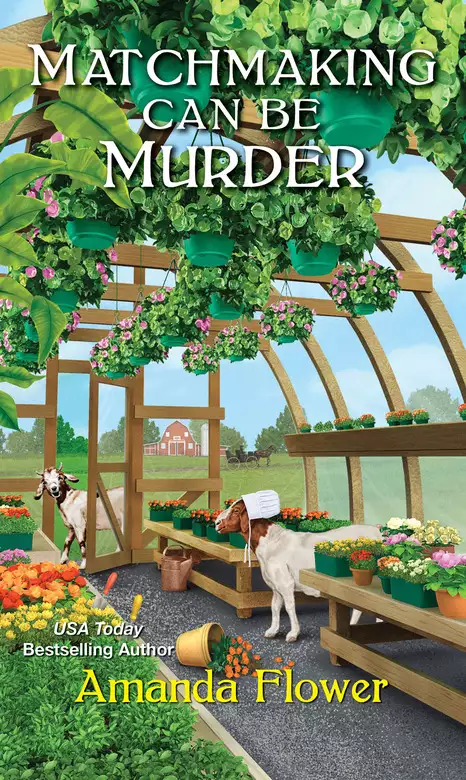

Edith ran Edy’s Greenhouse, a nursery that was just on the edge of the little village of Harvest where we lived. It had been her father’s business, Gott rest his soul, and he’d named it after his daughter, Edy, as he liked to call her. No one else in the family had been able to get away with calling her that. She ran the greenhouse herself now.

Her brother Enoch had chosen another life. Her business was the main reason that she shouldn’t marry Zeke Miller. The greenhouse did very well. Edith had a gift for plants and growing things that had been passed down to her from her father. Zeke knew there was money in that business and more to be made if he got his hands on it. If she married him, that business would become his. As her husband, he would be the head of it, not Edith. It was the Amish way for the head of house to be the head of the family business too.

And that was why I had asked her to come help me plant my garden—so we could have a heart-to-heart talk away from the prying eyes and eavesdropping ears in the greenhouse. This was a conversation that no one else should hear.

I wiped at my brow and knew I had a smudge of dirt now in the middle of my forehead. It itched. I didn’t bother to wipe it away. The dirt would add to the impression that I needed help putting in the plants and clearing the earth. The smudge gave the dramatic effect that I was going for. Edith wouldn’t be any the wiser.

My two goats, Phillip and Peter, walked around me in a large circle like lions stalking their prey. That would be if lions were as silly as these overly rambunctious creatures. They were Boer goats. Phillip was black and white, and Peter was brown and white. I’d adopted them when I moved back to Ohio after years in Michigan caring for an invalid sister. I bought them to help me clear the overgrown land around my home. Goats were the very best at clearing land. They would eat almost everything, but, surprisingly, wouldn’t eat grass. That was good. I wanted the lawn to stay intact. Phillip and Peter were doing a good job of chewing through the overgrown weeds and plants. They ate everything in sight, including the invasive multiflora roses that were the bane of any Ohio farmer due to their propensity to spread like wildfire and blanket the landscape with their treacherous thorns.

I found the goats circling suspiciously and picked up my spade to encourage them to move away from the freshly tilled earth. In all my sixty-seven years, I had never come across such ornery animals. I shook my finger at the goats. “This will be my flower garden, and if I see either of you in it, I will send you packing!”

Phillip and Peter shared a look.

“I know what you are thinking, but the garden is off limits. You—”

I would have said more, but just then there was the clip-clop of hooves and the rattle of a farm wagon on the other side of the house. Phillip and Peter took off. They loved to be first to greet visitors to my home.

I jabbed the spade into the lawn, rubbed a little dirt on my cheek to look frazzled, and made my way around the side of the house at a much slower pace than I usually tended to move.

As I walked around my ranch house, I reviewed what I was going to say. Somehow, I needed to convince Edith that it was better to wait for love than grasp at the first man who showed interest. There was a reason I had never remarried in the twenty years since I’d lost my Kip. I knew what true love was and would not accept anything short of it. I wanted my niece to find the same. I wanted all the young people I helped to find it too.

I removed my garden gloves and tucked them into the front pocket of my apron and touched the top of my head just to check my prayer cap was on straight and my snow-white hair, only a shade or two lighter than its original blond color, remained tucked tight at my nape. I had always hated my white-blond hair until it turned completely white, so it was not a great hardship for me when I started going gray. However, I could do without the wrinkles on my neck and the aches and pains when I rose in the early morning each day. I came around the side of the house just in time to see Phillip and Peter gallop like a couple of colts with their floppy ears flapping in the wind as they approached a petite blond Amish woman standing by a wagon. The back of the wagon was full of blooming plants.

Edith stood on her tiptoes, which only gave her an inch more on her five foot height. “Aenti Millie!” she cried. “Your gees are attacking me! Again!”

Gees was the Pennsylvania Dutch word for goats. It always made me laugh when the word was said around Englischers because I suspected they thought we were talking about geese.

“Phillip! Peter! You leave her alone, you rascals! Leave Edith be! If this keeps up, she won’t take you to the greenhouse.”

Peter stopped bouncing, but Phillip got in a couple more hops before he settled down on all four hooves. He was the more excitable of the two.

I snapped my fingers, which was a signal to the goats that I meant business, and they ran toward me, then began pulling weeds from the grass with their square teeth as if that had been their plan all along. I knew better.

“Rapscallions,” I muttered. It was an Englisch word I had heard while living in Michigan and I had come to like it quite a lot. It was one of the better names I could call the goats when they were really being troublemakers. My sister had lived in a predominantly Englisch community in Michigan. I’d learned all sorts of interesting words during my decade there.

Edith lowered herself from her tiptoes, keeping an eye on the goats the entire time. “I do appreciate your lending me your goats for a few days to clear the land behind the greenhouse. The weeds back there have gotten out of control.”

“It’s no trouble. Did you bring the wagon today to take them to the greenhouse?”

She nodded. “If you don’t mind, ya. The work is long overdue, and it’s something I can do to make a difference. I just need to do something to make things better at the greenhouse.”

“What do you mean, child?”

She shook her head. “It doesn’t look right for a greenhouse to have a messy yard. That’s all. I would have taken care of it months ago if I had been allowed.” Her face fell. “Things have been so challenging this season.”

I wanted to ask her what she meant by that, but before I could, she gave me a big hug.

“It’s so gut to see you. I wish that we could spend more time together. It’s just . . .” She trailed off.

“It’s gut to see you too, my dear.” I hugged her back and worry filled the back of my mind. A skill I had as a matchmaker was empathy for others. The emotion I felt most from my niece at that moment was sadness.

Of all my nieces, and I had many, Edith was the most dear to me. When I lived in Michigan to care for my sister, she came and stayed with us for a summer to help out. She was the kindest, most considerate girl, and I saw her more as a daughter than a niece. That may have been because her mother died young, just like my Kip. My sister-in-law’s death left my younger brother Ira Lapp with two young children to rear by himself. Because I had no children of my own, it made the most sense for me to be the sister to pitch in. I never regretted doing that. Some believed that I put life on hold to help Ira and then my sister in Michigan when she became ill. I never saw it that way. The only regret I had was failing Enoch, Edith’s twin brother. I hoped that I could make amends for that mistake soon.

I shook sad memories from my head and smiled at my niece. “And how are the children?” I asked.

“They are gut, Aenti Millie, and growing like summer weeds.” She said this with a mother’s glow.

“Dandelions, I hope. Those are my favorite weeds.”

“Aenti, there are a lot of Englischers who come into my greenhouse just to ask me how to get rid of their dandelions.”

“And if an Englischer does something, it is right?” I shook my head. “They are missing out on one of Gott’s great gifts. Next time they stop by and ask that, ask them to dig up their dandelions and give them to me.”

She laughed. “All right.”

“And how is Zeke?” I asked tentatively.

She licked her lips. “The wedding is next week.”

That wasn’t what I’d asked, so my eyebrows went up. “I know that.”

Zeke and Edith had only been betrothed since the winter. Typically Amish weddings happened in the autumn, but they didn’t want to wait that long because of the children, or so my niece had told me. We Amish do not have a long wait period between betrothal and marriage. When the decision is made, we get on with it. I knew things were much different in the Englisch world. My Englisch friends have had children who were engaged for a year or more. That would never do for the Amish.

“I’ve been thinking about what you said the other day. That I should only marry again for love. The greenhouse can sustain the children and me until I find love, or it will as soon as I make some changes.”

“What kinds of changes?” I asked.

She played with her bonnet ribbons as she spoke. It was a nervous habit she’d had ever since she was a little girl. “It’s just so frightening to be alone, and I have been alone these long three years raising the children the best I can without their father. The judgment of the community is heavy on my shoulders. I know there are many who believe I should have married long ago. They don’t believe it is right to raise children with only one parent. Then Zeke came along, and he was charming and helpful at first. He wasn’t afraid of the hard work at the greenhouse or that I had children. The district thought it was a gut match. You were the only one who didn’t.”

“Only because I wasn’t sure that you loved him. If you loved him, Edith, my thoughts would be different.”

“The community convinced me that I did. They said it was the best thing to do for the children.”

“If that’s not how you felt, you should not have listened to them. It’s far worse to marry the wrong person than to live alone.”

She nodded and dropped her bonnet ribbons so they fell to her shoulders. “I know this. I should only marry for love. You have told me so many times.” Finally, she looked up and met my gaze.

“And have you found love? With Zeke?” I asked, searching her dark brown eyes, which were the same color as mine.

She shook her head. “I don’t love Zeke. I—I don’t want to marry him. I—” She smoothed her white apron over her plain blue dress. “I thought over what you said about him, and everything is true. He does only want to marry me for the greenhouse.” Tears sprang to her eyes. “I don’t want to make another mistake like the one I did with my first husband, Moses, and marrying Zeke would be the greatest one yet.”

I blinked. Had I heard her right? “You’re sure?” I had been trying to convince her not to marry Zeke for weeks, and now, I hadn’t even had to put forth my latest argument.

“I only agreed to marry him because I was afraid of raising the children alone.” She took a shuddering breath. “I mean to tell him when he comes back from Millersburg today. He’s doing a roofing job there. I will tell him when he returns to Harvest. I have to tell him today. I can’t wait any longer. It’s killing me.”

It would seem that my ploy to get Edith’s help with my garden wouldn’t be necessary at all. I certainly hadn’t needed to smudge so much dirt on my face. I must look ridiculous. I suppressed my smile. I knew this was difficult for her to admit, and it would be even more difficult to tell Zeke. “You’re doing the right thing.”

She nodded. “But it will be so hard to tell him, to tell everyone that I changed my mind.”

“It is your mind; you have a right to change it. If it is not love, it is not Gott’s will for you.”

She nodded and squeezed my hand tight.

“Zeke will understand in time.” I patted her arm. “All will be well.”

At the time, I honestly believed that was true.

Edith was a good girl, and even though it was a Saturday near the end of May, one of the busiest days of the year for her at the greenhouse, when people bought the most plants and needed her sage advice about how to care for their gardens, she stayed for a while longer and helped me put the garden in. We worked in silence most of the time. I could tell she needed the quiet to sort out the thoughts in her head over what she was to say to Zeke that evening. I did not envy her the chore, but I would have done it for her if I could.

When she climbed back into her wagon an hour or two later, I reached up and squeezed her hand. “You will be fine, my dear. Gott is with you in all things.”

She nodded, but her body was as tense as a clothing line stretched from tree to tree.

Phillip and Peter were in the back of her wagon, tethered to the sides. They butted heads. A small part of me ached to see them go. I knew they would be back in a few days after they had cleared the land for Edith. But it would be a long, quiet night on my little farm without them.

“You will feel better when you can put this behind you,” I said.

She smiled down at me from her seat in the wagon. “This is true. It’s best to get the worst done as soon as possible, so that you can move on to the gut again.”

“That is right.” I grinned. “It seems to me that you have been listening to my favorite sayings all these years.”

Her smile fell into a frown. “I have always listened to your advice, Aenti, and if I have made the wrong choices along the way, that is my fault and my fault alone.” She flicked the reins on her wagon and the horse backed up and turned the wagon around in the driveway. I watched her go. The cries of the goats when they saw me staying behind pierced my heart. I would visit the greenhouse the next day to see how both Edith and the goats were getting on. I prayed Edith accomplished her difficult task before fear caused her to change her mind.

I brushed my hands on my skirts. It was time to head into the village for the Double Stitch meeting. I walked back to the house and tried to put these worries behind me. As the saying went, “Every moment of worry weakens the soul for its daily combat.” It was a saying I often repeated to Edith and Enoch when they were small. This one made me laugh a little to myself, considering we Amish were pacifists.

I drove to the village in my secondhand buggy, which was hitched to my mare Bessie, a gift from one of my brothers. She was a light brown Haflinger with a bright white star on her forehead. I was one of ten children. There were only four of us left in the world—two of my brothers and one sister—and now that I was back in Ohio, we all lived within an hour’s buggy ride of each other.

I inhaled deeply as I came to the outskirts of the village. The apple trees that had been in full bloom just a week ago were leafed out with bright green leaves. We were on the edge of summer, and the village of Harvest was getting ready for it. It was the busy season of the year in Holmes County. Busloads of Englischers would descend on the village, which was just what community organizer Margot Rawlings was counting on. From what I had heard, she wanted everything to be bigger and better in Harvest this year. If she was behind the idea, I didn’t doubt that it would happen. She was as stubborn as a bull and as clever as a fox.

On the village square, Amish men and a few Englisch ones were pruning and mowing and making sure that the grounds were perfect. In the middle of the gazebo, I saw Margot with her short brown curls, barking orders.

I flicked the reins and asked Bessie to pick up the pace. I didn’t want to get pulled into the fray with Margot. The best way to avoid that was to avoid eye contact. I parked Bessie and the buggy at a hitching post next to the big white church on the square. That was the place where Raellen, who’d organized our meeting that day at a new café in the village, had told me to park. I counted the other horses and buggies at the post, and it looked like most of the ladies from Double Stitch were already there.

I climbed out of the buggy and hurried down the sidewalk to the café. It was the first time I had been there, but the café was easy to find. It was a freestanding white brick building with a bright yellow sun painted on the side of it that was facing the church. A matching yellow awning hung over the front door. Giant planters of yellow tulips sat on either side of the door. It was bright and shiny and decidedly not Amish.

The last time I lived in the village, the café had been the local hardware store. I had gone into that store with my father and then with Kip many times. The shop had been Amish-owned, like most of the businesses in downtown Harvest, but the café that took its place was clearly an Englisch business. On the sidewalk chalkboard, the specials of the day were listed. Most of them were salads and soups with squash, kale, and berries of which I had never heard. These foods weren’t typical, not for me, anyway. Amish cooking was heavy on meat, potatoes, and pies of every kind. I wondered why Raellen, one of the members of Double Stitch, had picked this place for our meeting. Part of the motivation would be just to get out of the house. As a mother of nine, Raellen was always looking for breaks from her children and husband. I couldn’t say I blamed her. The sheep farm that she lived on with her family was in a constant state of upheaval. It seemed to me that every time I was there, either a sheep or a child was upset about something. Raellen, the Lord bless her, took it all in stride, and I thought she must have been given the greatest patience Gott had ever bestowed on any woman before or since.

I looked through the front window and noted that the decoration inside wasn’t very Amish either. Where our culture called for plainness, the café was anything but plain. The wallpaper was flowered and the tablecloths were covered with a colorful swirl pattern. Even so, many of the features from the old hardware store were still intact, such as the exposed brick wall and some of the pine shelving along those walls. Now instead of tools and nails, the shelves held brightly colored dishes. On another chalkboard on the wall, the specials and the soup-of-the-day were written out.

I opened the front door and a bell chimed. Raellen Raber, my bubbly next-door neighbor and mother of nine children, was already seated with two of the other members of Double Stitch, Iris Young and Leah Bontrager.

Iris was the mother of one fifteen-year-old son. She was a beautiful woman with auburn hair, delicate features, and skin that already held the sun-kissed glow of working outside. She had been very popular with the young men in the district until I introduced her to Carter Young, an industrious young man who had moved to Holmes County from Geauga County to help his grandparents with their farm. Carter’s grandmother had implored me to find Carter a match, so that he. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved