- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

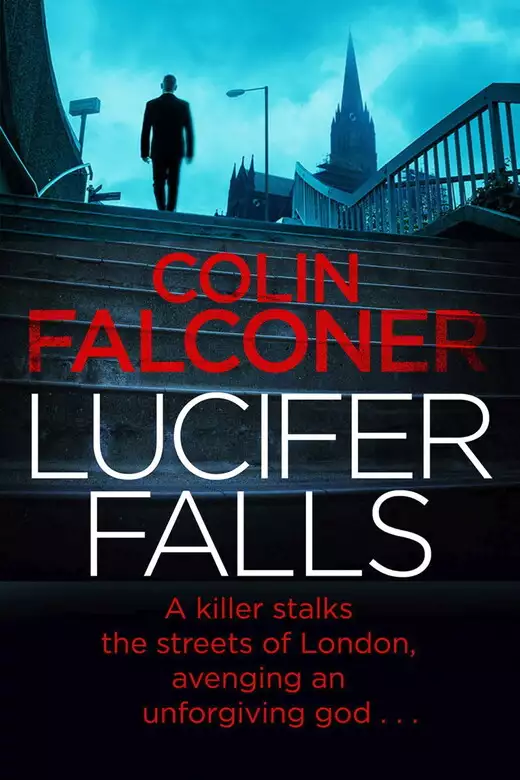

Synopsis

A killer stalks the streets of London....

When a priest is found crucified in a derelict North London chapel, it makes a dramatic change for DI Charlie George and his squad at Essex Road. The brutal murder could not be further from their routine of domestic violence and stabbings on the estates.

And that's only the beginning....

On Christmas Eve, a police officer goes missing, and his colleagues can't help but anticipate the worst. It turns out they're right to when eventually the body is found and they discover he's been stoned to death.

As tensions rise, it's up to Charlie and his team to venture into the city's cold underbelly to try to find an answer to the madness...before anyone else dies a martyr's death.

Release date: December 27, 2018

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Lucifer Falls

Colin Falconer

How the hell did he get up there?

The victim’s arms were suspended directly above his head, fixed to the rough timber with a nail the size of a railway spike. Blood had leaked down his arms and the top of his chest and dried into a brown crust. His legs had been broken.

He was naked except for a priest’s collar and a wooden crucifix around his neck. His expression had been frozen by rigor; he looked as cheerful as a man might, in the circumstances. If he really was a priest, Charlie thought, it was a poignant way to die.

‘Jesus Christ,’ Greene said.

A moment. Charlie heard the plaintive cry of a crow from the trees.

‘Seriously Jay?’

‘It was the elephant in the room. Someone had to say it.’

Charlie shook his head and turned away. One of the CS officers nodded to him and pulled down his face mask. ‘Morning, Charlie. I thought we’d had Halloween.’

‘What have you got, Jack?’

Jack nodded at the photographer, who was standing on a small, aluminium stepladder, taking close-ups of the stone sill.

‘Grooves in the stone, made by a rope or a chain.’

‘That’s how he got him up there?’

‘Looks like it. Take a butcher’s at this.’ He turned and went outside. Charlie followed.

There was a bit of rubbish strewn around, beer cans and crisp packets and toilet paper; the grass was still crisp with frost. A feathery grey mist hung in the trees.

Under the branches, the gravestones in the cemetery were soured with age and all about the place, in a jumble. Still, the dead had long lost any reason to be tidy. They were actually just fine when they were left alone. He wondered for a moment how many of them had been murdered. One in six hundred and twenty-five, if you believed the statistics.

On the other side of the cemetery railings London was still going about its business, pounding horns, texting, looking at Facebook on the bus.

‘See these marks here,’ Jack said, pointing at the frozen mud about twenty feet from the Gothic windows. ‘What it looks like, he had a van or a truck with a winch. Attached the end of the chain to the top of the cross and hoisted it up, using the wall as a lever.’

‘It’s a lot of trouble all this. Anything else?’

Jack nodded at two other CS officers in their blue overalls, on hands and knees in the grass. ‘Footprints. Good impressions, too; mud must have been a bit softer when he made them and they froze overnight. We’ve taken casts. There’s some smaller tyre prints, could be a mover’s trolley.’

‘Right. For getting the victim into the church.’

‘It would have made life easier.’

‘What you mean is, it made death easier. Crucifixion in the twenty-first century. I wonder if he used a nail gun?’

‘You’d need a power source.’

‘I was joking.’

‘Know you were. But that spike wasn’t put in here, there’d be blood splatter.’

‘You’re right. Interesting.’

‘Whole bloody thing is interesting, if you aren’t the poor sod he did it to.’

‘He or she, Jack. Let’s not jump to conclusions.’

‘It’s a he. What would a woman be doing with a winch?’

‘Who found the body?’

Jack nodded to the patrol car, parked under the trees, a little way up the gravel drive. A man was sitting in the passenger seat, his head between his knees, holding an emesis bag. Two uniforms were standing over him. One of them was taking notes.

Charlie went over. ‘All right?’ he said.

‘Sir,’ they both said, in unison, when he showed them his warrant card.

‘Is he OK?’

‘Still in shock, sir. We’ve called an ambulance.’

Charlie squatted down. ‘Detective Inspector George, Metropolitan Police. Was it you that found the body?’

The man looked as if he wanted to say something, instead he gagged into the bag. Charlie jumped up and took a step back, didn’t want any of that on his Fratelli Rossettis.

‘What happened?’ he said to the uniform with the notebook, a stocky young woman with an earnest expression.

‘He was doing his rounds first thing this morning. He knew something was wrong when he found the chains on the front gates had been broken.’

‘Doing his rounds?’

‘He checks for vandalism every morning, sir. He’s one of the Friends of the Cemetery.’

‘The cemetery has friends?’

‘Eleven, sir.’

‘Christ, it has more mates than I do. So, he comes down here every morning at this time?’

‘They have a roster.’

‘All right, when he’s feeling better get a statement. I want the names and addresses of all the cemetery’s Friends. And its enemies as well.’

‘Sir?’

‘It was a joke, Constable.’

He went back inside the chapel. Years since it had been used, by the looks; it was closed to the public these days, most of the windows boarded up with corrugated iron and mildewed plywood, the stained glass all gone. Their perp had used bolt cutters to snap the chain on the padlocked gate in the vestibule.

He stood there for a moment, admiring the way the light angled into the chapel through a hole in the slated roof. Nice. An overhanging tree had worked its inquisitive fingers through one of the high arches. There was the smell of leaf mould. On a transept wall he could make out a piece of ancient graffiti, CASEY LOVES COCK. I wonder if she still does, Charlie thought. She’d be a grandmother by now.

Greene hadn’t moved, was still standing there, staring at the body.

‘No spear wound,’ he said.

‘What?’

‘Rules out the Romans.’

‘What are you doing, Jay? This is not a laugh.’

‘I was trying to get inside his mind, guv. The murderer, I mean. It looks like he’s arranged everything, like a tableau.’

‘A tableau?’

‘A tableau’s like a representation of a scene from a story.’

‘I know what a tableau is, thanks.’

‘What I mean, guv, is that if you want to off someone, it’s easy enough. You just hit the geezer with a brick. But this, this is like, art.’

‘What are you, a profiler now?’

‘The thing is, why the bloody performance?’

‘That, my old son, is what makes the job interesting. Just when you think you’ve seen everything, you get a crucifixion in an abandoned church. Brilliant.’ His mobile rang. ‘DI George.’ He listened, said ‘right then’, and hung up.

‘Who was that, guv?’

‘Jolly. He’s got held up in the traffic. No point in us hanging around then. Let’s get back to the nick.’

They walked back to Greene’s Sierra, threw their overalls and overshoes in the boot, and climbed in. Charlie let Greene drive, they bumped back down the footpath to the front gates.

Charlie took out his iPhone and did a quick Google search.

‘It’s a Dissenters’ Chapel,’ he said.

‘What is, guv?’

‘The place your artist chose for his tableau. Dissenters were like Quakers and Anabaptists, Christians who didn’t believe in the Church of England so they built their own. This one was put up in 1840. Hasn’t been used for years. Careful!’

‘What?’

‘You nearly ran over a squirrel. I like squirrels. You run over a squirrel, I’ll get you transferred to traffic duty. Says they recorded an Amy Winehouse video here.’

‘Popular little place, then. One of the uniforms said that during the day the locals use it for walking the dog.’

‘Is that a euphemism?’

‘A what?’

‘Look it up. It’s in the dictionary next to Tableau.’

There was a jumble of tombs on either side of the path, some collapsed, others overgrown with ivy and brambles. They reached a pair of imposing Victorian gates, blue and white police tape everywhere, three more uniforms from the local nick keeping the curious at bay.

Charlie scrolled down the screen on his mobile. ‘God love us.’

‘What, guv?’

‘It says there’s two hundred thousand people buried in here. That’s more people than Southend.’

‘And they’re about as lively.’

They drove through the gates and they were back in North London, a dour streetscape of betting shops and pawn-brokers, a Salvation Army shop squeezed between a Pizza Hut and a Morrisons. There were Hassids in gabardine raincoats and side-curls, Nigerian mothers in bright wraps. Charlie had grown up not far from here; it wasn’t like that then.

He quickly checked the Arsenal website before he shut down the phone; Arsène Wenger was still hanging on, he’d been hoping he’d resign. Greene saw his expression.

‘What’s up, guv?’

‘Nothing.’ He pointed out of the driver’s side window, at the CCTV camera mounted on the other side of the bus stop. ‘Let’s hope that’s working.’

He made a mental note of the row of shops on the other side of the road, flats built over them – someone must have seen or heard something. He didn’t want this one getting away from him; people mustn’t think they could crucify someone in the middle of London and get away with it. Next thing, everyone would want to do it.

Dawson, his inside DS, was waiting for him back at the nick, with a mug of coffee. Most of his team were already at their desks, the phones ringing off the hook as usual.

‘Who’s that?’

‘She’s our new DC, guv. Lesley Lovejoy.’

‘You having a laugh?’

‘No, guv.’

‘Did I know about this?’

‘I sent you an email, last week. She’s from CID.’

‘Email? You only sit ten feet away, can’t you just talk to me?’

He went over. She stood up and held out her hand; cropped blonde hair, a blue trouser suit, sensible shoes, no make-up. ‘DC Lovejoy.’

‘Sorry, you’ve got me at a bad moment. No one told me you were coming. You done homicide before?’

‘No guv.’

‘You’re about to hit the ground running. Where were you before?’

‘Kensington.’

‘Do they have murders in south west London?’

‘The kids knife each other for their Yeezy Mud Rats over there.’

‘Well, pay attention, I’m sure we’ll find something for you to do.’ He went into his office, there was an email from Jack already. He printed off the first shots from the crime scene and went into IR1, started pinning them to the whiteboard.

One by one the rest of the team trickled in. Dawson, Wesley James and Rupinder Singh stood behind him, their arms folded. He heard Wesley swear under his breath.

‘OK team, here’s one for the ages. Found at around 6.15 this morning in the abandoned chapel in Barrow Fields cemetery. We can’t confirm TOD at this stage, but the cemetery is locked overnight so it is safe to assume the crime took place then. The PM will give us a more exact time. Crime Unit believes that the victim was attached to the cross elsewhere and transported afterwards.’

‘How did they get in?’ Dawson said.

‘Bolt cutters.’

‘Once he was in,’ Rupinder said, ‘how the hell did he get him up there?’

‘We are speculating that an electric winch was used, and that it was possibly attached to a van or lorry. There were deep grooves in the brickwork above the window.’

‘That’s mad, that is.’

‘What sort of sick batty boy would do something like that? It looks like—’

‘You say tableau, Wes, and I’ll thump you.’

‘I was going to say, like art.’

‘That’s as bad.’

‘He’s wearing a dog collar,’ Rupinder said.

‘That looks like a priest’s crucifix around his neck,’ Lovejoy said. ‘It’s too solid for bling.’

‘Doesn’t mean he’s a priest though, does it?’ Charlie looked at Greene. ‘Could be part of a tableau.’ He held out a hand. ‘Everyone, if you haven’t met her already, this is Detective Constable Lesley Lovejoy, she joins us from Kensington CID, and was lucky enough to arrive this morning for her first day.’ He turned and looked at her. ‘Our first job is to ID our victim, so as soon as we finish up here, I want you to get on the blower to MisPers, find out if a priest has been reported missing in the last seventy-two hours.’

She got up and leaned in for a closer look.

‘Haven’t seen a crucifixion before, Detective? You probably don’t do a lot in South London, but we get a lot of these, especially in Hackney. This is our third this week.’

She didn’t smile; if she didn’t have a sense of humour, she wouldn’t last long in this unit. He was about to get on with the briefing when she said: ‘That’s not a proper job though, is it? He meant him to die quick.’

‘Meaning?’

‘His arms above his head like that. He wanted him to die fast.’

‘What do you know about it?’

‘I used to be a Catholic, guv.’

‘Lot of people used to be Catholics.’

‘It’s just I was curious about it when I was a kid, so I looked it up. He’s done him the quick way.’ She walked out, went back to her desk and picked up the phone. Charlie looked at Dawson and nodded. More to that one than meets the eye.

‘Rupe, Wes, we need CCTV, everything in a mile radius of that cemetery, business, residential, government.’

They nodded.

‘Where’s his clothes?’ Dawson said.

‘There’s uniforms from Malden Street combing the cemetery looking for them. Don’t fancy our chances. Gale, you and Malik head out to Barrow Fields, there’s houses back on to the cemetery and flats that look right over the front gates. Start knocking on doors, someone must have heard something.’

A tall man in a dark blue suit appeared in the doorway, cleared his throat. Charlie looked up. ‘Morning sir.’

‘My office. Now.’

He walked off.

‘You have been summoned,’ Dawson said and grinned.

Detective Chief Inspector Fergus O’Neal-Callaghan reigned over the North London Major Incident Teams from a corner office on the fifth floor of the Essex Road nick. It was all glass and chrome, not a piece of paper in sight, his ceremonial uniform and peaked cap on the coat hanger behind the door.

A small, framed photograph of a smiling family sat on the shelf behind him. It had been there a while; his boys were grown, both off at university by now. Still, having a family at all, it was something to be proud of, in this job.

The walls were filled with citations, and photographs of him with various dignitaries. What was it Greene had said about him?

‘If he was a lolly, he would have sucked himself to death.’

From up here the view wasn’t spoiled by the train station and the shabby allotment behind Newington Row. The only interruption to the vista were the floodlights of the Emirates stadium.

‘Sit down, Charlie. So, what have we got?’

‘Bloke with two broken legs nailed to a bit of wood in a derelict church, sir. Know as much as you do at this stage.’

‘Who is he?’

‘We’re still working on that.’

‘I don’t want to jump the gun, but I feel this could get messy. You think it was some kind of satanic ritual? Some gay BDSM thing? Like that thing with Boy George and that Swedish bloke a few years back?’

‘Norwegian. And if it is Boy George, sir, he really did want to hurt him.’

No smile.

Charlie went on. ‘As you say, sir, it’s too early to make any kind of call. Once we’ve got an ID and the CS reports from Lambeth, I can set a direction. What are we doing about the media?’

‘I’d like to keep the more lurid aspects of this out of the papers.’

‘You want me to do the press?’

‘Christ, no. I’m not sticking you in front of a camera. I’ll brief Catlin to do it. That’s what she’s paid for. We’ll just say we found a body, and we’ll keep mum about the cause of death or the journalists will have a field day. What about the fellow who found the body, can we impress on him the need for discretion?’

‘We can try. I haven’t eliminated him as a suspect just yet.’

‘All right, well keep me informed on this one.’

Charlie got up to leave.

‘This is a bit close to home for you, isn’t it?’

‘Sir?’

‘Isn’t your brother a bit churchy?’

‘You mean the one who’s a priest?’

‘A priest. Oh. I didn’t know it went that far. Never picked you for a left-footer.’

‘Lapsed.’

‘Well, it doesn’t matter. Just get a result on this one. This is the sort of nasty business that is not good for our careers.’

He means my career, Charlie thought.

‘What are you looking at, Charlie?’

‘Your shoes, sir. I’ve got a pair just like that.’ He almost said: I keep them for gardening, but he stopped himself, just in time.

They stared at each other.

‘That’s all, Charlie.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

He went out.

‘So, what do you think of the newbie then?’ Greene said. They were in the Sierra, driving to the mortuary.

‘We don’t think anything yet. We don’t judge on appearances.’

Greene shrugged, fidgeted. He wasn’t done.

‘Think she’s a gusset muncher?’

‘I have no interest in her sexual orientation and, if you’ve got any sense, Detective, you won’t pay it any mind either.’

‘Well, yeah, but. You know. The clothes, the haircut. You have to wonder, innit?’

‘No, you don’t have to wonder. You don’t have to do anything. The only thing we are paid to wonder about is the poor sod in the morgue and how he got there, but professionally and privately, I reach the wild borderlands of my wonderment right there. Mind that cyclist. Christ, did you ever have driving lessons? Turn left here. There’s a space in the car park over there. Come on, let’s get this over with.’

It was refrigerator cold inside the morgue. The buzz and flicker of a fluorescent light put Charlie on edge as they gowned up. They went through a pair of plastic slab doors. He wrinkled his nose at the chemical smell. It turned his stomach.

It wasn’t like the new place in Haringey, this was all grim Victorian tile and dull steel sloping towards the drains on the floor. The government pathologist, Henry Jolly, was standing next to a white-coated technician, staring at a display of X-rays in a light box. He was wearing a green apron. Some of his breakfast was still in his beard. He was wearing Crocs with paisley socks and denim jeans, a size too large.

He nodded to Charlie and motioned him over. ‘Sorry I missed you this morning. There was a bus versus motorbike on the M25.’

‘We didn’t mind,’ Greene said and nodded to the corpse. ‘But this geezer was hanging about for hours.’

Jolly looked at Charlie as if Greene was his fault. No one smiled.

He returned his attention to the light box. ‘You are looking at the tibia and fibula bones of the deceased’s right leg. As you can see, not a clean break; the bones were shattered at the point of impact. Usually the type of injury seen, for example, from the kick of a horse. This X-ray here is the ulna and radius of the right arm. The joints at the elbow and the wrist have been completely disarticulated. Extraordinary.’

The victim lay supine on a stainless-steel gurney. Paul, the CS photographer, was already at work with a camera, taking video and stills of the injuries. Usually, he would talk to the mortuary technician about the football as he worked – they were both smug Chelsea supporters – but today neither of them was saying very much. Even they seemed a little appalled, and they must have thought they had seen it all. Until this morning, he had thought that too.

‘Hell of a job getting him into the mortuary van,’ Jolly said. ‘His arms were fixed in the position you found him. I had to break the rigor before I could start work.’

Charlie wasn’t much interested in his problems transporting the body, or the methods for chemically breaking rigor, but he listened patiently while Jolly explained it all in detail.

‘Unusual case,’ Jolly said, when he had finished his story.

‘Understatement.’

The victim’s hands and head had been bagged. Jolly removed the bags and then untied the gag on the victim’s mouth. There was another rag inside his mouth, Charlie saw, to prevent the poor sod from screaming. ‘Linen,’ he said. ‘Almost bitten through.’

He took off the dog collar and the cross; they went into the plastic evidence bags that Greene had brought with him. Greene wrote on the labels and attached them.

‘Crucifixion,’ Jolly said and pursed his lips. ‘Interesting history. It was invented by the Persians, apparently, hundreds of years before the crucifixion. Alexander the Great once crucified two thousand people at once, outside the walls of Damascus, for having the temerity not to surrender to him. Awful way to die. When the arm muscles give out and are unable to support the body, the shoulders, elbows and wrists all dislocate. The arms can be up to six inches longer when the victim is finally taken down.’

‘I’ve always wondered, what’s the cause of death? In crucifixion, I mean.’

‘You mean, apart from extreme evangelism,’ Jolly said.

‘Yeah, apart from that.’

‘There are a number of theories. After the shoulders disarticulate, the chest sags and the victim is left in a permanent state of inhalation. Because they can’t breathe out, it is only possible to inhale tiny sips of air.’

‘So, they suffocate?’

‘As a pathologist, I couldn’t put it quite that simply. You see, with the onset of anoxia, the carbon dioxide levels in the blood increase and so the body tissues become acidic and start to break down. This causes fluid to leak into the lungs and makes them stiff, so it’s even harder for the victim to breathe, which intensifies the suffocation process. But this fluid can also leak into the pericardium, so death might result from cardio-rupture or pulmonary embolus before hypoxia is complete.’

‘So how long would it have taken this poor sod to die?’

‘This fellow? Oh, not long. No more than an hour.’

‘I thought Jesus died after nine hours. That’s what they taught me in Bible class.’

‘Well, you see, it depends what method is used. With arms outstretched in the classic pose you see in most churches, death may be delayed for twenty-four hours or even more. But whoever did this, knew a little about anatomy.’

‘The perpetrator pinioned the arms directly above the head to hasten death,’ Charlie said, remembering what Lovejoy had said.

Jolly smiled. ‘I see you’ve been doing your homework. Yes, when the arms are fixed directly above the head, as this fellow’s were, it becomes almost impossible to breathe. Also, his legs were broken to ensure that he couldn’t support his body weight with his feet.’ He nodded towards the pulpy, open fractures on the shins. ‘I would say a blunt instrument was used, a tyre iron or a baseball bat.’

‘After he nailed him up.’

‘That’s difficult to say.’

‘So, he didn’t die from blood loss?’ Greene said.

‘You mean, from the trauma to his wrists? No, the blood loss from the puncture wounds would not have been significant. The pinion was placed between the junction of the radius and ulna bones, avoiding major blood vessels like the radial artery. As I said, whoever did this knew what they were doing.’

‘And breaking his legs was like an act of mercy?’

They both looked at Greene.

‘What?’ Jolly said.

Charlie looked up at the strip lights, closed his eyes. Jesus, he worried about the lad sometimes. How had he ever made sergeant? ‘Yeah, he had a heart of gold, Jay. Proper Saint Teresa.’

‘I would venture,’ Jolly said, ‘that if I shattered the bones in both your lower legs with a heavy, blunt object, you would hardly consider me benevolent.’

‘So he did it,’ Charlie said, ‘to ensure that his victim expired in the manner intended before anyone could find him?’

‘It would appear so.’

‘Time of death?’ Charlie asked him.

‘From the extent of rigor, I’d say early hours of the morning. Between midnight and three a.m.’

Jolly took fingerprints and swabs for DNA then began a careful examination of the entire body. ‘Look at this,’ he said.

He pointed to the soles of the cadaver’s feet.

‘Brick dust,’ Charlie said.

‘It’s quite different from the limestone in the transept, where he was found. Of course, there’s brick in other parts of the church. I’ll get samples for comparative testing. You see, there’s another patch here on the left elbow.’

‘Jack believed he was stripped and nailed to the upright somewhere else, then brought to the chapel.’

‘Ah, look at this.’ Jolly pointed to a small bruise on the thigh. ‘It’s a puncture wound, the kind you would expect from a hypodermic needle.’

‘He was sedated?’

‘Possibly.’

‘How long to get a toxicology report?’

‘Everyone wants everything yesterday, Charlie. This is not the only homicide in London this week.’

‘It’s the only crucifixion.’

‘Doesn’t make you special.’

‘I’m under a bit of pressure here, know what I mean?’

‘Aren’t we all?’

Charlie stood in the car park, took a couple of deep breaths, looked up at the sky, enjoying the feel of the icy drizzle of rain on his face. He felt hot and he felt sick. Always the same, no matter how many times he did it. He didn’t know how Jolly could do that for a job.

‘Act of mercy,’ he said to Greene. ‘What’s wrong with you?’

‘Did you see the size of the hole in his wri. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...