- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

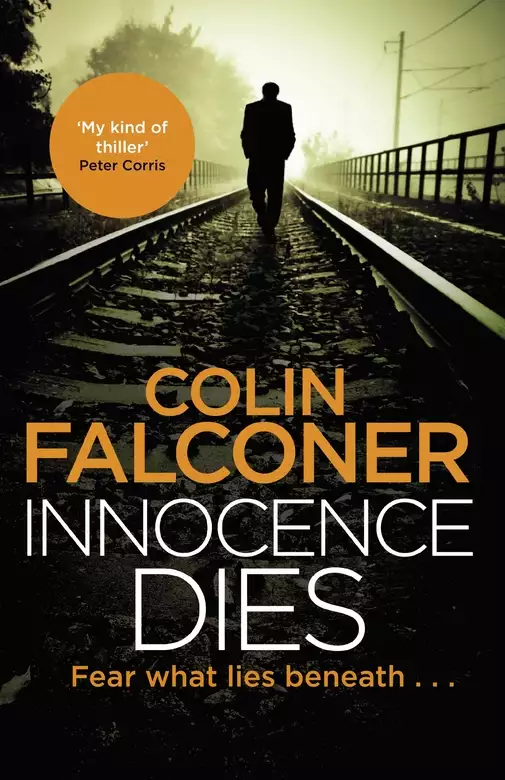

Synopsis

'Dripping with authenticity. Packed full of characters you genuinely care about . . . I didn't read the last few chapters, I devoured them. An absolute triumph' M. W. CRAVEN

He loves surprises. But not this one.

A schoolgirl is found dead in a park in North London and DI Charlie George is not short of suspects - is it her stepfather? Is it a sex crime? Is it race-related?

Charlie finally thinks he has it sorted, with his killer bang to rights. But then his lawyer gets him free on a technicality.

And that's just the start of his troubles.

He's been a cop all his life, he thought he'd seen everything . . . But Charlie soon realises, he hasn't seen anything yet.

Release date: October 3, 2019

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Innocence Dies

Colin Falconer

The musical phrase had quite a different meaning for DI Charlie George; it told him that someone, somewhere, had lost their life through an act of extreme violence.

The Nokia on his bedside table belonged to the Force, regulation issue. He stared at the glow from the LED display in the dark, listened to it buzz and vibrate for a few grim seconds before he reached for it. He had thought about changing the default to something more appropriate for the distress and ugliness he was being summoned to; something already ruined for him. Pre-fucked, as DC Jayden Greene would say.

Kanye West, for instance.

He sat up, had the feeling of being dragged out of a play halfway through. Already the roseate world of his dreams was slipping away; he tried to hold on to it, a hand reaching back in a fast-flowing stream. No, it was gone, not even a few cold details to mull over when he was scraping the frost off his windscreen a few minutes from now. It had been a good dream, with a good woman in it, and Arsenal winning. Nothing at all like reality.

He flicked on the bedside lamp, picked up his Oliver Coen Berkeley and peered at it. 2.37. Nice. Come on, Charlie son, pick up the freaking phone. The duty officer isn’t going to change his mind and ring someone else. You’re on call, mate. Your shout.

‘DI George?’

He didn’t recognise the voice. Must be the new one, what was her name, Barnes, Barnett? No, Bartlett.

‘It’s DS Barlow at Essex Street.’

Right, that was it; close.

‘Yes, Barlow.’

‘Suspected homicide on a disused rail line in Finsbury Park. The HAT team are out there now. An eleven-year-old girl, missing since yesterday evening.’

His first thought: who finds bodies on a railway line in the middle of the night? That was one for the early morning joggers. Well, he supposed he’d find out soon enough. He scribbled down the details for his GPS, wished Barlow a good morning, and hung up.

A dead kid. Oh, great. He felt like he’d swallowed a cup of cold fat. He knew what that was like, too; his old man had made him do it once when he caught him stealing a bit of chicken out of the fridge.

He hated homicides involving kids; something you never got used to, they reckoned, no matter how many years you racked up in the job. ‘Orpheus descending into the Underworld,’ he said and got out of bed.

He stared at the clothes in his walk-in; he still missed his old place, this was like hanging up his suits in a phone box. He thought about his Corneliani suit, forty quid at a Salvo in Chelsea; the Incotex smart casual trousers, still hadn’t worn them; the Marni trainers bought for a tenner at a market stall down the road. But they weren’t for jobs like this. He grabbed one of his regulation navy CID suits, ninety quid at TK Maxx, and got dressed.

His car keys were on the bedside table, next to his phone.

He peered down into the street. There was a sheen of ice on the pavement.

He stumbled down the stairs, put on his Stone Island, hurried out of the door and nearly went arse over breakfast down his front steps. There was a high-pitched squeal; it sounded like a stuck pig, scared the bejesus out of him. He fumbled in his jacket for his iPhone, turned on the torch.

‘What the fuck,’ he said and bent down.

It was a dog, a cocker spaniel by the looks, shivering with cold, all skin and bone like a puppy. No collar on it. It licked his hand, the crafty bugger.

‘What are you doing here?’ Charlie said. ‘Get yourself off home.’

The spaniel scrambled to its feet and trotted inside.

‘No, you can’t do that. I’ve got to go to work.’

The little dog sat himself down in his kitchen, half sitting, half leaning against the refrigerator door. He was still shivering, stared at him with its big sad eyes like he expected him to do something about it.

‘You’re wet,’ Charlie said.

He grabbed a towel from the linen cupboard, dried him off as best he could. He went to the cupboard, got an empty beer box, put the towel in it to make a bed. He sorted through the shelves; there was a half-eaten packet of chocolate digestives. No, he’d read somewhere that dogs couldn’t have chocolate. It would have to be the Rich Tea. ‘Sorry mate, I ate all the custard creams,’ he said, scooped the damned thing up under one arm and put it in the box. ‘Look at you, you’re all ribs, like an underwear model. Doesn’t anyone ever feed you?’

Well, now what? He put the box under his arm and went out to the car.

I must be mad, Charlie thought. Who takes a spaniel to a crime scene? ‘If you crap in my car,’ he said to the dog, ‘there’ll be two bodies to sort out.’ He wondered where the bloody thing had come from; no one in the block had a dog, far as he knew, at least nothing bigger than a terrier. How was he going to find the owner? Facebook, he supposed. The spaniel didn’t look as if he was missing anyone in particular, though, the state of him.

He hesitated a moment before getting in his car. But what else was he going to do? He couldn’t leave the dog in the flat and he couldn’t leave it to freeze on the doorstep.

He clicked the key remote, put the box and the spaniel on the floor on the passenger side. He got out one of the Rich Teas and gave it to him. ‘Christ, you inhaled that. Didn’t your mother teach you to chew your food?’ He gave it another one, same result.

‘Here, have the packet, why not,’ he said, tossed the biscuits in the box with the spaniel and shut the door. He used the plastic scraper to get the frost off the windscreen, then got behind the wheel and warmed up the engine. He turned on the GPS. Seven minutes to Finsbury Park, according to Mrs Google. He wondered what was waiting for him.

He put the car into gear. He could feel the cocker spaniel looking at him.

‘You have the right to remain silent,’ he said. ‘Use it.’

Charlie slowed at the police checkpoint, leaned out of the window to show his warrant card to a uniform in a high-viz jacket, and signed in. He parked behind a dark blue Beemer. Christ, the DCI was here. Was it that bad?

The local Bill had cordoned off the high street either side of the railway bridge. He could see the glow of the Crime Scene unit’s halogens on the embankment; a nice climb up an icy slope then, that’s the way to start a day.

The cocker peered at him over the edge of the box. ‘Unless you’ve got a certificate showing me you’re qualified as a sniffer dog, you cannot come to a crime scene,’ Charlie said. ‘So just sit here and be quiet. Don’t eat all the biscuits and, for real, don’t crap in my car.’

As he got out, his breath misted on the air. A few moments later it started chucking it down again, the weather gods conspiring to stuff up his crime scene. He went to the boot, got his white coveralls and shoe covers, struggled into them, got a fresh log book, then headed up the embankment. The CS team had set up their blue and white tent about a hundred yards further down the track; only there was no track, it looked as if there hadn’t ever been one. He shone his torch around. Everything on the embankment either side was grown over with weeds.

He headed towards the scrum of CS officers, all in their papery white hooded suits and face masks. It looked like a scene from a sci-fi film.

One of them pulled down his mask. ‘Morning, Charlie. All right, then?’

‘Bit nippy, Jack.’

‘This rain’s not doing us any favours either.’

‘What have you got for me?’

‘You’ll not be best pleased. Victim’s father trampled over everything before we got here, the weather did the rest. The local guvnor’s bringing in extra uniforms to do a search.’

‘What is this? Thought it was a railway.’

‘Meant to be, back when Jesus was a boy, then someone changed their mind. Now the locals use it for dogging and drug deals.’

‘It’s always good to have a designated area. Lobbying the council for one where I live, next to the skateboard park. What’s that over there? Public toilet?’

‘Ventilation shaft for the underground. It’s all locked up.’

‘The tube go under here?’

‘Not any more.’

They were moving the body. Two lads from the Forensic Medical Examiner’s office had loaded the body bag on to a stretcher and roped some uniforms into helping them carry it back to the bridge. Rain had beaded on the heavy-duty green plastic.

‘The FME’s been and gone,’ Jack said. ‘Your guvnor’s still here.’

‘Brilliant.’

‘Good luck,’ Jack said.

Inside the tent it was hot from the lights, the slap of the rain all but drowning out the murmur of voices. Two of his Homicide Assessment Team were still there, Ty Gale and Lovejoy. Lovejoy looked a bit green under the lights. He nodded to her. ‘OK?’

‘Yeah, I’m OK, guv.’

‘You don’t look OK.’

‘Well, dead kids. I’ve been doing this job long enough, but it still upsets me.’

‘That’s all right then. Not good to get too cynical. When it stops upsetting you, tell me, and I’ll get you transferred to traffic.’ He turned to Gale. ‘Where’s Malik?’

‘He’s taken the father home.’

‘Jack told me the victim’s father was here.’

‘He was the one that found her, guv.’

‘That a fact. Did you get any kind of statement?’

‘Got it on my phone. He was quite lucid, which surprised me. Calm. It was a bit odd, like.’

‘What’s his name?’

‘Raymond Okpotu. The victim’s name was Mariatu. Her family’s from Sierra Leone.’

‘That where she was found?’ The tent had been put up over and around a clump of brambles. Two SOCOs were still at work, on their hands and knees.

‘He said he found her lying right there, face down. She was reported missing …’ He checked his notes, ‘… at 7.40 p.m. yesterday evening. The 999 call was logged at 12.07 a.m.’

‘He went looking for her in the middle of the night and just happened to find her right there.’

‘Apparently.’

‘The FME say anything?’

‘He said he was cold.’

‘After you exchanged pleasantries.’

‘Massive head wound. Blunt-force trauma.’

‘Murder weapon?’

Gale shook his head.

Charlie slapped the log book into Lovejoy’s arms. ‘That’s yours. You can follow me around on this one, see how it’s done. Every decision gets written down in there, along with date and time. Anywhere I go, you go. Almost.’

He went back outside; the DCI was talking to someone, they both had their hoods back.

‘FONC,’ Lovejoy murmured, and she managed to get the tone just right. She was learning fast. ‘What’s he doing here, guv?’

It was four in the morning, chief inspectors didn’t get out of bed for just any old dead body. This was the sort of murder that could really bunch the commissioner’s pants; was it a hate crime, sex crime, what? Both? This would need a steady hand or the locals would be burning cars and chucking bottles at uniforms in full riot gear. Never mind the crime wave sweeping London, blokes on mopeds with zombie knives. This could turn political.

‘Charlie.’

‘Guv.’

‘This is Inspector David Mansell from Crouch End. This is his borough.’

Charlie shook hands.

‘Bad business,’ Mansell said. He nodded towards the houses on either side of the embankment, lights blinking on in kitchens and upstairs windows. Word must have got around, people were waking up to police cordons and halogen lights. ‘I’ve called in my entire duty roster to help with the house-to-house. Someone must have seen or heard something.’

‘And we appreciate your assistance,’ the DCI said to Mansell. ‘Will you excuse us a moment? I need to consult with my DI about a private matter.’

Mansell was taken off guard. He raised an eyebrow and nodded. ‘Of course. Keep me informed.’

FONC stared at Lovejoy, who was still at Charlie’s shoulder. ‘It’s all right,’ Charlie said to her. ‘You don’t need to log this.’

The DCI waited until she was out of earshot.

‘You up for this Charlie?’

‘Sir?’

‘Well, you’ve only just come back on the roster. I was hoping to ease you back into things. This is not what I had in mind.’

‘It’s a murder investigation like any other.’

‘No, it isn’t. A murder investigation like any other is a gangbanger with a knife in him, not an eleven-year-old Somali schoolgirl.’

‘She’s from Sierra Leone.’

‘Whatever. How’s your arm?’

‘The arm is fine. Even if it wasn’t, I don’t need my arm to run a murder investigation.’

‘It’s not your arm I’m worried about.’

‘I’ll be fine.’

‘You’d better be. I want twice-daily briefings. Any major developments, let me know immediately. You know what immediately means, don’t you?’

‘Within a day or two.’

‘Don’t be a smartarse.’

‘No, sir.’

‘I want swift progress.’

He stamped back towards the bridge. Charlie looked at Lovejoy, shivering and wet in her blue coveralls; she suddenly looked very young, too young for this job. He felt that way too, sometimes.

‘He’s in a good mood,’ she said.

‘He’s under a lot of pressure,’ Charlie said. They found the uniforms who had been first response by their patrol car, sheltering from the rain under the bridge. Charlie waited until Mansell had finished debriefing them, then went over.

‘You were first responders?’ Charlie said. ‘What happened?’

The older of the two cops spoke up. ‘We got the dispatch while we were on patrol, blue-lighted our way over. When we got here, there was an IC3 standing at the top of the embankment up there, yelling and waving his torch about. We followed him up.’

‘Mr Okpotu.’

He checked his notebook. ‘That’s him. By the time we got up there, he’d run back to the girl’s body, picked her up. He was holding her in his arms, wouldn’t let go of her.’

‘Did he say anything?’

‘Said a lot of things, but most of it was in his own lingo, like. He only used English if we asked him a direct question.’

‘Did he say where he found her?’

‘The bushes where Crime Scene have the tent, that’s what he reckoned.’

‘And then?’

‘We called for back-up, cordoned off the area as best we could, but I mean, all the bleedin’ good it would do, he’d already trampled all over it.’

‘How did he seem?’

‘Matter of fact,’ the younger cop said. ‘Weren’t he, Sarge? You’d think he’d be more upset.’

‘Did he say what position she was in when he found her?’

‘He said he’d come across her lying face down in the bushes,’ the sergeant said. ‘She had this …’ He touched the back of his head. ‘Just here. It was a pulpy mess. He had her blood all over him.’

‘Was she dressed?’

‘He told me her knickers were down around her knees. That was what he said. He’d pulled them up again before we got there.’

‘Do you know if there had been an attempt to conceal the body?’

‘No. Said she was just lying there.’

‘And no sign of a weapon?’

They both shook their heads.

‘Thanks fellas.’

They went back to their patrol car. It was raining harder now, rivers of it gurgling as it gushed down the drains. Charlie decided to wait for it to ease up. He turned to Lovejoy. ‘See how the rain kicks up, when it’s this heavy? When I was a kid I used to tell me little brother they were rain fairies dancing.’

‘And he believed you?’

‘Well he was only eight. Kids believe anything when they’re eight. Anyway, he liked it, stopped him being so scared of thunderstorms.’

When it eased off they ran for Lovejoy’s car, which was parked closer than his Golf. He got the decision log kicked off, named the victim’s father as his initial suspect. One of their first priorities would be to make him a focus of further enquiries or rule him out.

‘Can you hear a dog barking?’ Lovejoy said when she’d finished writing it up.

‘Fuck, I forgot,’ Charlie said.

He ran back to his car. The cocker wagged its tail so hard when he opened the door, he thought its bum was going to come off. Charlie couldn’t say he was quite so pleased to see the cocker. It had eaten all the biscuits, including the wrapper, and had crapped all over his passenger seat.

‘Never took you for a dog person,’ Lovejoy said over his shoulder. ‘Oh look, he likes you.’

‘Get off me, dog,’ Charlie said. ‘You’re getting shit on my jacket.’

Lovejoy picked him up. ‘Sorry guv, but are we supposed to bring pets to murder scenes?’

‘I found him on the doorstep as I was leaving, what else could I do? Look at him, he’s starved and he’s wet. He needs some TLC.’

‘And leaving him locked up in your car in the dark is your idea of tender loving care, is it? What kind of dog is he?’

‘He’s a cocker spaniel.’

‘He looks like a bloodhound.’

‘Trust me, he’s a cocker. I grew up with one.’

‘We only ever had short-haired dogs. What are you going to do with him?’ The cocker was trying to lick Lovejoy’s face while she made baby talk at it. A different Lovejoy, this; not the same one that had a black belt in judo.

‘Can’t do sod-all with him, Lovejoy. I live alone in a flat and I work all hours.’

‘My dad will have him. His old Lab died a couple of months ago, I’ve been telling him he needs another one to keep him company. It can be just temporary, if you like.’

‘Is he going to leave it banged up in a yard all day on its own?’

‘No, he’s on a pension. Like I said, he needs the company. It’ll be a good home for him till you get it sorted.’

‘All right. But if he’s on a pension, I hope he can afford plenty of Rich Tea biscuits. The little bugger eats for England. Come on, we’d better get back to the nick. We have work to do.’

An absolutely filthy dawn, grey as gunmetal and rain spattering on the windscreen, like someone was throwing gravel at it. Not even the camera crews could be bothered, and neighbours were reduced to peering out through net curtains, so the street was almost deserted except for two miserable uniforms standing outside the front gates in their ponchos. Oh well, that had been him once, it was good motivation to pass your detective exams first time.

The Okpotus lived in a large semi with Gothic windows and bargeboards. He could make out the hilly heights of Mount View to the north.

‘Simon Pegg lives round here somewhere,’ Charlie said. ‘You know, Shaun of the Dead.’

‘He’d be over in Crouch End, wouldn’t he?’ She pronounced it, crouchon, as if it were French. He laughed.

He told Lovejoy to stay in the car and look after the spaniel. They’d had to come in hers, the Golf would need detailing before he could use it again. He waited for the rain to ease then made a dash for it.

Charlie seemed to remember that he and his brother Ben had got beaten up round here somewhere, by a bunch of pikeys, after they gatecrashed a party. Those were the days. And the last time he was here it was on his first and last Tinder date, some girl from Crouch End who wanted him to pull her hair and smack her with a hairbrush while they were having sex. Not his thing really, but dinner had been the business: nettle soup, and chicory and wild garlic gnocchi.

There was a child’s plastic ride-on tractor lying on its side in the driveway. Malik was waiting for him in the car port, some polycarb roofing giving protection from the rain.

‘Morning, guv.’

‘Malik. All right, then?’

Malik puffed out his cheeks, lit up, offered him one. Charlie shook his head. Hadn’t had one for a while now, he’d felt quite virtuous putting ‘non-smoker’ on the admittance forms in A&E, wondered if he could keep it up this time.

‘Who’s in there, then?’

‘Mr Okpotu is just wandering around like he’s in a trance. Mrs Okpotu is upstairs. Doctor’s been round, had to sedate her, she was a right bloody mess.’

‘Kids?’

‘Three, she was the oldest. They’re in the kitchen with aunts, uncles, you name it. The mullah is there, too. Watch him, he’s got a lot of opinions, know what I mean?’

‘What’s the story, then?’

‘She came home from school, around quarter to four, went up to her room. Must have sneaked out again. When her mother went to call her for dinner, about seven, she wasn’t there. They rang round all her friends. When none of them said they’d seen her, they rang the local nick.’

‘Which friends?’

Malik pulled out his notebook, tore off a sheet. ‘Here, I made a list.’

‘What happened then?’

‘The local Bill took it serious because of her age, and started a low-level search, but they told them there wasn’t much they could do until the morning. Anyway, about eleven, Mr Okpotu said he couldn’t stand the waiting and went off on his own with a torch.’

‘And found her pretty much straight away. Lucky, that.’

‘According to him, he was searching for an hour, knew the places the local kids like to go.’

‘Anything on him on the PNC?’

‘No, nothing.’

‘Look, we’ve got to establish a timeline for all this. You’ll have to speak to everyone in the family on their own, find out when each of them reckons they last saw Mariatu alive. But softly, softly, all right?’

‘Sure.’

‘Ty reckons there’s something funny about him.’

‘Maybe he’s on the spectrum or something. He’s in IT,’ Malik said, like that meant something.

‘I hate this,’ Charlie said. ‘Kids.’

‘Me too, guv,’ Malik said, and Charlie remembered how Malik had told him once how his little brother had died when he was ten. Full marks for being sensitive, Charlie.

He went in. There was a lot of shouting coming from the kitchen, sounded like they had the old Arsenal North Bank in there.

There was a framed photograph on a rough-hewn wooden table, a family portrait, carefully posed, the Okpotus with Mariatu and two younger girls. So that’s what she looked like, pretty and a little chubby. He doubted that he would recognise her the next time they met.

The door to the living room was open, wooden masks and bright-coloured rugs on the walls, wooden sculptures on the bookcase, some polished bark with words he didn’t recognise carved into it.

Suddenly the door to the kitchen burst open and a short, bearded man in a turban and a grey thobe rushed out. ‘Are you the chief inspector?’ Without waiting for a response, he said, ‘What are you doing about this? Why are you here? Why aren’t you out catching the monster who did this to one of our children?’

‘And you are?’

Another man came out, lanky, clear-eyed, almost serene. ‘Please, Imam Ahmad, let me talk to them. It is all right, they are doing their job.’

The cleric looked like a balloon about to burst, but he allowed himself to be pacified. The tall man put a hand on his shoulder and guided him back to the kitchen, but as he was going through the door the imam turned around and gave Charlie and Malik a look of venom. ‘This is what we get for letting our little ones play with white children.’

‘It’s not their fault,’ the tall man said.

The cleric pointed a forefinger at Charlie, but he was looking at Malik. ‘You should go; go and take your Malteser with you!’ The door shut behind him.

Malik just shrugged and gave Charlie . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...