- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

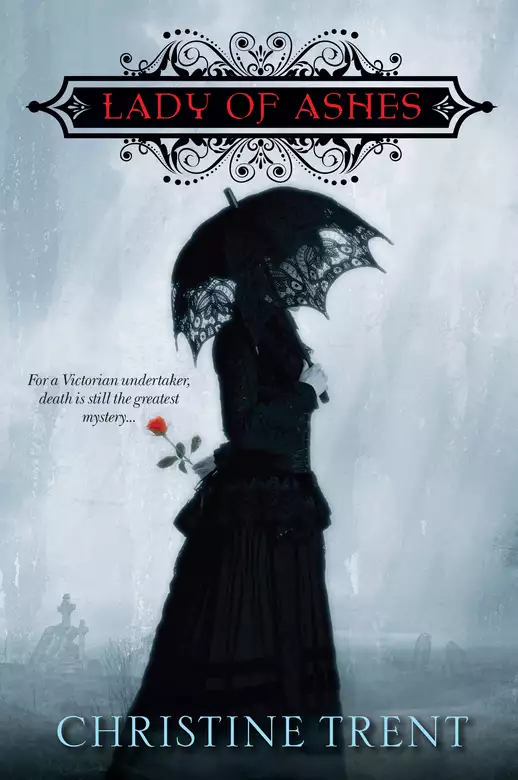

A female undertaker in Victorian London suspects death by unnatural causes in a mystery "rich with historical incidents and details" (Publishers Weekly).

Only a woman with an iron backbone could succeed as an undertaker in Victorian England, but Violet Morgan takes great pride in her trade. While her husband, Graham, is preoccupied with elevating their station in society, Violet is cultivating a sterling reputation for Morgan Undertaking. She is empathetic, well-versed in funeral fashions, and comfortable with death's role in life—until its chilling rattle comes knocking on her own front door.

Violet's peculiar but happy life soon begins to unravel as Graham becomes obsessed with his own demons and all but abandons her as he plans a vengeful scheme. And the solace she's always found in her work evaporates like a departing soul when she suspects that some of the deceased she's dressed have been murdered. When Graham disappears, Violet takes full control of the business and is commissioned for an undertaking of royal proportions. But she's certain there's a killer lurking in the London fog, and the next funeral may be her own.

Release date: March 1, 2012

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 434

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Lady of Ashes

Christine Trent

May 1861

Violet Morgan often wondered why she was so skilled at dressing a corpse, yet was embarrassingly incompetent in the simplest household task, such as selecting draperies or hiring housemaids.

If only they hadn’t moved to fancier lodgings in a more elegant section of London, she wouldn’t be burdened with having to learn a myriad of rules for keeping a proper home. Surely her domestic mismanagement was the source of her husband’s current displeasure. How else could Graham have become so morose and embittered these past few months? Surely it wasn’t the hot weather, which had never before made him so bilious.

Violet picked through her tray of mourning brooches, organizing them neatly for the next customer who wished to make a purchase. She slid the tray of pins into the display case and reached for the pile of papers Graham must have carelessly thrown on top of it. She sorted through the mix of invoices, newspapers, and advertising leaflets. A recent copy of The Illustrated London News caught her eye. Graham had circled headlines regarding events in the United States and scribbled in his own comments beside them. Her husband was avidly following current events transpiring across the Atlantic, hoping for destruction on both sides of the U.S. conflict.

One article opined on the expected duration of the conflict raging there. The Americans had recently engaged in hostilities, after years of Southern states bickering with those in the North. Since last month’s first firing of shots at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, much taunting and posturing had occurred. How the citizens of the United States enjoyed fighting. Each side boasted the skirmish would last just a few months, and self-proclaimed experts declared that all the blood to be spilled in the contest could be contained in a single thimble, or wiped up by one handkerchief.

The newspaper agreed, but Violet felt that was foolish optimism. England’s own civil war had gone on for almost a decade and nearly destroyed the country.

And to what end? The Roundheads eliminated the monarchy with the beheading of Charles I in 1649, and by 1660 the monarchy was back with his son, Charles II. Nothing changed, but thousands of lives lost and a king beheaded. Surely the Americans would end up with a fallen leader, too.

Another article, which Graham had not only circled, but drawn brackets around, focused on the South’s hunger for recognition. During the past couple of months, the Southern states had pressed Britain to recognize their burgeoning nation. The poor fools thought they had Britain in a state of helplessness because they controlled much of the world’s cotton, so necessary for England’s cloth mills. They didn’t realize that England had been storing cotton for some time and was flush with it. What the country did need was wheat.

Wheat was produced by the Northern states.

The crafty British politicians, though, were willing to host a confederate delegation in London and let it press its suit for diplomatic recognition, thus not publicly rejecting the South in case it should win the war.

Violet sighed as she separated the pile of papers into related stacks before removing another tray to straighten, this one full of glass-domed mourning brooches. Buyers could weave the hair of the deceased into a fanciful pattern and place it under the glass to create an everlasting keepsake to be pinned to one’s breast.

To think of all those American soldiers who would die ignominious deaths, heaped into mass graves, without the distinction of a proper funeral and burial. How could her husband, a man whose profession was to bring dignity to death, wish for mass slaughter?

She replaced the second tray. The display case looked much better now that it was tidied up inside and out. She moved over to the linen closet, its door discreetly hidden in the wallpaper at the back of the room. Inside were shelves stacked with bolts of black crape for draping over windows, black Chantilly lace for mourning shawls, and fine cambric cotton for winding sheets. Except the cambric had all tumbled to the ground in a heap. How had that happened?

“Graham?” she called out. “Did you let our cambric fall to the floor?” Only when there were no customers at Morgan Undertaking would she dare raise her voice above the gentlest of tones.

“For what reason would I have done that? Maybe Will was the sloppy one going through it,” he replied from the shop’s reception area.

Perhaps, but Will was usually as careful as Violet.

Violet glanced at the mantel clock over the fireplace. Nearly ten o’clock in the morning, time to visit the Stanley family. She gathered up her cavernous undertaker’s bag, filled with embalming fluids, tinted skin creams, cutting tools, syringes, fabric swatches, and her book of compiled drawings of coffins, mourning fashions, flowers, and memorial stones. Going to the display case, she pulled out a selection of mourning jewelry and added the pieces to her bag.

Violet lifted her undertaker’s hat from its stand and tied the sash under her chin. The extra-long, flowing tails of black crape wrapped around the hat’s crown were a symbol of her trade. Graham wore his own hat adorned with black crape when meeting with customers, as well. She peered into a mirror she kept next to the hat stand, pinched her cheeks to bring some color into them, and tucked an errant strand of hair under the brim of her hat before putting on black gloves. In his more jovial days, Graham used to tease her that one day he’d be rich because he’d cut off and sell her long hair, which he deemed the color of newly minted bronze ha’pennies and of even more value in its beauty.

With a quick farewell to her husband, she left the premises and boarded a horse-drawn green omnibus for Belgravia. Graham always insisted that they hire private cabs for transport to meetings with grieving families, contending it was more representative of the Morgans’ socially elevated state, but Violet was still uncomfortable with their new entry into higher circles and usually ignored his demand. She wasn’t quite sure their income supported the luxuries Graham contended were their due. The omnibus, London’s horse-drawn public transport, cost a mere threepence to travel to most places through central London, and only sixpence to travel farther out.

She exited the omnibus a few blocks from the address she had been given, and walked the rest of the way.

The Stanleys lived in an up-and-coming neighborhood on the outer edges of Belgravia, an area known for its wealthy—and usually aristocratic—residents. The Stanleys’ townhome wasn’t quite as stately as the residences nearby, being situated in a long row of recently built units that reflected the current construction craze in London.

Nevertheless, this district was a few steps up from the London locale where she and Graham had settled after inheriting his father’s undertaking shop. Graham’s ambition was eventually to move to Mayfair, maybe even Park Lane, yet Violet was just as happy in their Grafton Terrace townhome in Kentish Town, a very respectable area north of Regent’s Park.

Mostly respectable, anyway. They did have odd neighbors, Karl and Jenny Marx, who named all of their daughters after Jenny. Mr. Marx seemed to have no occupation other than writing letters and essays every day, sometimes under the name “A. Williams.” There was also neighborhood gossip that Mr. Marx, or Williams, had fathered a child with his housekeeper, but Violet stayed out of such tittle-tattle. She lived in a pleasant area and had no desire to stir up anything ugly.

There was no black crape festooned under the windows and above the doors of the Stanley residence. Violet made a mental note of it as she pressed the “Visitors” bell. Some debate existed as to whether or not an undertaker should be using the “Servants” bell, but in Violet’s opinion, anyone assisting the family with a proper departure from their earthly existence was certainly entitled the rank of Visitor.

A maid with swollen eyes and dressed in black opened the door. Immediately recognizing who Violet must be by her garb and large black bag, the young woman silently led Violet to the front parlor and closed the door before going to seek out her mistress.

The Stanleys were far wealthier than she and Graham were. A new grand piano, polished within an inch of its ivory-keyed life, stood prominently in one corner as a testament to fashion. The windows were draped in three separate layers of material, a sign that the Stanleys took current trends very seriously. Multiple linings were expensive, but kept out the dirt, heat, and noise from the street. The papered walls proudly displayed paintings and bric-a-brac, while the wood floors were covered with bright, intricately designed carpets. Violet’s own attempts at interior decoration fell far short of the Stanleys’ remarkable expressions of taste.

Here was a family that would demand a funeral of nearly aristocratic proportions.

The same maid opened the door to the room again, and a middle-aged woman, haggard beyond her years and dressed head-to-toe in black, entered. Violet nodded solemnly.

The other woman spoke first. “Mrs. Morgan? I’m Adelaide Stanley. Thank you for coming to attend to my Edward.” The woman brought an extravagantly laced handkerchief to her eyes. “I can hardly believe he’s gone. Such a good husband he was. I don’t know how we’ll manage.” Mrs. Stanley twisted the soaked handkerchief in her hands.

“God finds a way to help us manage,” Violet said, pulling a spare cloth from her sleeve and discreetly handing it to the woman, who accepted it with a fresh flow of tears. “Where is Mr. Stanley?”

“Upstairs in his bedroom. So calm and peaceful he was when he passed. Like an angel, despite the torture he endured from pneumonia. Do you wish to see him now?”

Violet considered. Mrs. Stanley was truly grieving, but was relatively composed, unlike some of the hysterical relatives Violet usually encountered, so it might be best to address practical matters first in case her customer should later collapse.

“Why don’t we discuss Mr. Stanley’s ceremony first?” she suggested.

“Of course, as you wish.” Mrs. Stanley rang a bell and gave instructions for tea to another maid who appeared, dressed much like the first one. Violet and her customer sat in deeply plushed, heavily carved chairs and chatted innocuously until the maid returned. After steaming cups had been poured, the maid withdrew, and Violet pressed into the delicacy of arranging a proper funeral.

“I saw immediately upon approaching your elegant front door that Mr. Stanley was a man of some importance, is that not so?”

“Indeed. Edward made us quite comfortable through investment in the London and Birmingham rail line back in the forties. Once it merged with Grand Junction and the Manchester and Birmingham Railways, well, Edward had proven himself to be a very astute investor. He had many influential friends.”

“Quite so. And this parlor tells me you are a woman of impeccable taste. Your extensive blue-and-white china collection is to be commended.”

Mrs. Stanley was no longer crying. “You are kind to notice, Mrs. Morgan. Mr. Stanley and I strove to present the right sort of furnishings befitting our station. The china is all antique, you know, none of those newly manufactured pieces that have become so popular with the masses.”

Violet shifted uncomfortably in her chair. Graham had ordered several new imported blue-and-white vases and jardinières to ornament their home.

“Of course,” she replied, removing her gloves and opening her bag, which lay at her feet. “Mr. Stanley wasn’t part of a burial club, was he?” Violet withdrew her undertaker’s book.

“My, no. We never expected him to go so soon. We never had any thought of it.”

“Actually, I applaud the fact that you never did this. Many burial clubs are operated by unscrupulous undertakers who tell grieving widows that they cannot pay out the money until the club’s committee meets in three months’ time. Naturally, since the burial must be completed quickly, she cannot wait, and the undertaker offers to loan her the money, and charges an exorbitant sum for the funeral.

“My husband and I would never engage in such a practice. I’m simply relieved that we don’t have to try to wrest your money from such a club. You and Mr. Stanley were very wise not to have been deceived by one of these dishonest groups.”

Violet reached over and patted Mrs. Stanley’s hand, and received a grateful smile in return. She continued. “There is much you can do to ensure Mr. Stanley’s status is properly recognized at his funeral. Let me show you.” Laying the book open in her lap so that Mrs. Stanley could see it, Violet flipped through sections marked “Poor,” “Working Class,” and “Tradesman,” stopping just short of “Titled” to the section marked “Society.”

“Most people of your position opt for a hearse with two pairs of horses, two mourning coaches each with pairs, nineteen plumes of ostrich feathers as well as velvet coverings for the horses, eleven men as pages, coachmen with truncheons and wands, and an attendant wearing a silk hatband.”

Mrs. Stanley’s eyes grew wide. “Oh my. Is all of that necessary?”

Violet flipped backward in the book to the section marked “Tradesman.” “Please be assured, we can assist you at a variety of levels. We could pare down to a hearse with a pair and just one mourning coach, and reduce the mourning company to just eight pages and coachmen.”

“And that is the standard for what those in the trades do?”

“Yes, madam. For a tradesman such as a railway officer or a solicitor. The cost of such a funeral is around fourteen pounds sterling.”

Mrs. Stanley frowned. “And for the other one? With all of the horses and mourners?”

“A bit more, at twenty-three pounds, ten shillings.”

“I see. That is certainly well within our abilities. It wouldn’t do for my husband to have a funeral that wasn’t worthy of him.”

“No, madam.”

“Tell me, what sort of cof—resting place—would my husband have?”

“An exceptional one, made of inch-thick elm, covered in black and lined with fine, ruffled cambric; a wool bed mattress; and the finest brass and lead fittings on the coffin. Its quality would be nearly that of an aristocrat’s. See here.” Violet flipped to a page containing a line drawing representing the coffin she was suggesting.

Mrs. Stanley nodded. “A beautiful resting place for my Edward.”

“Very elegant, I agree. Now, Mrs. Stanley, do the Stanleys have a plot or mausoleum?”

“His family is at Kensal Green.”

“Perfect. A lovely garden cemetery.” It truly was. It had attracted many prestigious families and even some royalty. Augustus Frederick, the Duke of Sussex, as well as Princess Sophia, uncle and aunt to Queen Victoria, were both buried there. The princess rested in a magnificent sarcophagus.

“But they’re in the crypt under the chapel. We never thought about purchasing a mausoleum in a better section. We never imagined anything would happen to him,” Mrs. Stanley said in explanation for why the newly wealthy Stanleys were not in a more exclusive part of the cemetery.

“Please don’t fret over it, Mrs. Stanley. Take your time purchasing a location and we can move your husband later.”

Violet steeled herself for the next question she must ask. “Mrs. Stanley, tell me, do you wish to have your husband embalmed?”

The look of horror that passed over Mrs. Stanley’s face was a familiar sight. “Heavens me, no! What an un-Christian-like thing to suggest,” the widow said, a hand across her heart.

“My apologies, I have no wish to offend. It’s just that Mr. Stanley would be . . . available . . . longer if he was embalmed, and you could therefore have more visitors.”

Violet hardly had the words out of her mouth before Mrs. Stanley was emphatically shaking her head. “Absolutely not. My husband will be buried naturally, as all respectable people are.”

Embalming was a new concept in England. Although the practice had been around for centuries, with the ancient Egyptians routinely employing it as one of their many types of funeral practices, it had been mostly limited to royalty in Europe, and even then not frequently. The Americans whom Graham despised so much were already making use of it for their battlefield dead, and the French had written extensively on the merits of the practice, but, thus far, Morgan Undertaking had only performed it on a handful of corpses. Most people were still suspicious of doing something so unnatural to a body that would shortly be committed to the ground.

Violet, in particular, ran into difficulties with families who found it unseemly that a woman would be desecrating a newly deceased person by making cuts, draining blood, and injecting fluids to prolong the freshness of the corpse. Putrefaction typically started within twenty-four hours of death, requiring profusions of flowers and candles around the coffin during visitation, as well as a quick interment.

Violet jotted notes in a small ledger tucked at the rear of the book. “Very good, madam. We have a cooling table that we can place under the coffin to keep him comfortably set during visitation. I’ll arrange for your husband’s placement and will direct the procession to the cemetery personally. And may I make a few suggestions regarding other accoutrements that might aid you during this difficult time?”

For the next hour, the women discussed further purchases, including black crape for draping across the front of the house, photography of Mr. Stanley in repose, memorial cards, and mourning stationery.

Finally, Violet pulled out her tray of mourning jewelry, made mostly from jet, a popular material derived from driftwood that had been subjected to heat, pressure, and chemical action while resting on the ocean floor. “These pieces are made in one of the finest workshops in Whitby, Yorkshire, Mrs. Stanley. You’ll find no better than what I have here.”

The new widow picked out a glittering necklace and earrings for herself, both intricately carved, as well as simpler pieces for her two adult daughters, who would be arriving from Surrey in time for the funeral. Violet noted the purchases in her ledger.

Shutting the ledger and putting everything away, Violet addressed their final matter. “I would like to see Mr. Stanley now.”

Fresh tears welled up in his wife’s eyes. “Yes, of course, this way, please. Two of my maids have already washed him.”

Family members or servants frequently handled the initial preparation of the deceased, and in poorer families they might handle all details regarding attendance on the body to save money.

Clutching her bag, Violet followed Mrs. Stanley up a wide staircase in the center hall of their townhome to the next floor of the four-story home. From the top of the landing they walked to the rear of the townhome to a shut door. Mrs. Stanley took a deep breath before opening it and entering, with Violet at her heels.

The room did not yet even have a musty odor to it, despite the heat. Given Mr. Stanley’s large figure prone on the bed, she guessed he must have only been dead less than a day. The more corpulent the deceased, the quicker the decay. She glanced at a mantel clock in the room, which was stopped at four twenty-three, confirming that he had just died the previous afternoon. Clocks were traditionally stopped at the time of death to mark the deceased’s departure from this current life and into the next. Tradition held that to permit time to continue was to invite the deceased’s spirit to remain in the home instead of moving on.

Violet waited near a window while Mrs. Stanley went to her husband, who appeared to be sleeping quite peacefully under a coverlet, kissed his brow, and said, “My dear, the lady undertaker is here. I called for her because I thought she would be most tender with you. I hope you aren’t angry with me for not hiring a gentleman undertaker.”

She kissed her husband on the cheek this time and patted his chest, then nodded silently to Violet as she slipped out of the room, still teary-eyed, and let the door gently click shut behind her.

This was the part Violet both revered and dreaded, for her almost indescribably heavy responsibility toward both the deceased and his family.

She approached the body and set her bag down on a large table along the wall across from the bed. “Good afternoon, Mr. Stanley, it is a pleasure to make your acquaintance,” she said, opening the bag once again and pulling out an array of bottles and a wooden box containing her tools. She arranged her bottles in the order they would be used.

Transferring the box of tools to the bed, she pressed the latch to open it. In what would have been seen as a bizarre gesture by the outside world, Graham had given her this set of Sheffield-made tools to celebrate their fifth wedding anniversary three years ago. Each time she opened the box now, she was reminded of how glorious their married life had initially been.

Graham and his brother, Fletcher, had been trained by their father, known as old Mr. Morgan, to take over the family undertaking business, which had been established by their grandfather in 1816. But Fletcher had a taste for the sea and eventually set himself up as a trader, taking tea to Jamaica, picking up sugar from that country, selling it in Boston to be made into rum, and returning with barrels of finished rum for sale to the Englishmen who craved it.

When old Mr. Morgan died, therefore, Fletcher was happy to let Graham buy out his share of the business. Soon after, Violet met Graham at a church social and was immediately fascinated by the work he did.

For his part, Graham seemed fascinated by a woman who was not repulsed by an undertaker.

Violet reached over and gently squeezed the deceased’s hand. Rigor mortis, the chemical change in the muscles that caused the limbs to become temporarily stiff and immovable, had not yet set in, much to her relief, else she’d need to return the following day to finish her preparations, creating undue anxiety for his widow.

Her and Graham’s relationship developed amid explanations of coffin ornaments, funeral hospitality, and the care of the dead. Within a year, twenty-year-old Violet Sinclair and twenty-three-year-old Graham Morgan were married, and took up residence with his mother, who remained in her own home after her son and daughter-in-law eventually moved to their more upscale lodgings. Together Graham and Violet rode in each day to their working premises on Queen’s Road in Paddington, joyful in their death profession as only two young people in love could possibly be.

Violet sighed as she took out several jars of Kalon Cream. If only her life had remained so happy.

“Now, Mr. Stanley, this might look a bit frightening, but let me assure you that it won’t hurt a bit. I promise to be gentle and to fix everything so that your wife will hardly notice that I have had to muddle about with you.” Graham had taught her that talking to the deceased helped wash away the dread of working with a dead body. Many customers also talked to the deceased, and those who did, like Mrs. Stanley, seemed to adjust better to their losses.

She examined the contents of each jar, finally deciding that “light flesh” was the right shade. She scooped out some of the cosmetic, a dense covering cream that she rubbed into Mr. Stanley’s face and hands. A corpse naturally paled as blood pooled downward, so cosmetic massage creams helped bring a more lifelike appearance back to the body.

After wiping her hands on a cloth, she used a paintbrush to apply a pale rouge to the man’s cheeks and lips, thus further enhancing a living appearance. Once she was satisfied with his visage, she unrolled a length of narrow tan cloth and snipped off about a foot of it. She threaded a special needle, then sewed one end of the cloth to the skin behind one ear. Next, she pulled the cloth tightly under his chin, then sewed the other end behind his other ear.

The cloth would prevent Mr. Stanley’s mouth from dropping open accidentally during his visitation and frightening dear Aunt Mollie or Grandma Jane as she was bent over whispering last words to him. Sometimes, instead of this method, she used a small prop under the chin, later covered by the deceased’s burial clothes. Every undertaker had his own methods for preparing a body, and those methods were trade secrets.

“All finished, Mr. Stanley. I trust it wasn’t too uncomfortable for you. We’ll need to get you arranged in the parlor for visitation, then you’ll have a journey of great fanfare to the cemetery. But first we must get you properly attired.”

She’d forgotten to ask Mrs. Stanley to provide her with burial clothes. Well, there was no help for it, she couldn’t possibly ask the woman back in here now, with her husband in such condition. Violet went to the enormous mahogany armoire that loomed in one corner of the room and searched until she found what she assumed was Mr. Stanley’s finest set of clothes. She selected a shirt with the highest collar possible to cover the jaw cloth.

Dressing a dead body was exceedingly difficult to do alone, making Violet wish she had Will or Harry, the shop’s muscular young assistants, with her. However, Graham had them busy on other assignments, so it couldn’t be helped.

Trying not to grunt aloud, Violet pushed and pulled Mr. Stanley’s limbs and torso as she struggled to undress him and place him in his finery. Once he was dressed and his hands positioned decorously on his chest, Violet packed up her bag and straightened out the bedclothes, ensuring no evidence of her work was left behind. That was something else Graham had taught her. An undertaker must be like a housemaid: all work performed invisibly and with as little inconvenience to the family as possible.

She returned to the parlor, where Mrs. Stanley was pacing back and forth, worrying the handkerchief Violet had given her between her fingers. “How is my Edward?”

“Resting quite comfortably, Mrs. Stanley. I think he would be quite pleased with how you’ve provided for him.”

Violet assured Mrs. Stanley that she would accompany the coffin, along with a bier, for setup in the parlor the following day. “May I recommend that you perhaps go visit a close friend tomorrow and allow me to escort Mr. Stanley to the parlor privately with one of our assistants?”

“Yes, yes, of course. Whatever you say. You’ll be careful with my husband, won’t you?”

“Madam, I will treat him as if he were my own husband.”

Perhaps she should quit using that turn of phrase, since lately Graham’s behavior would have made her more than happy to see him trade places with Mr. Stanley.

Violet dropped her carte-de-visite, or calling card, which offered her compliments on one side and the Morgan Undertaking address on the other, on the silver salver in the hallway on her way out, pleased with how this customer visit had transpired and anxious over what mood Graham might be in when she returned.

“Where have you been?” Graham asked as she untied her hat, combed out the tails with her fingers, and hung it on its stand in the back room. She tossed her black gloves on a nearby shelf.

“At the Stanley residence near Belgravia. Our commission from Mr. Edward Stanley’s funeral should enable you to buy a marble bust or two for your collection.”

“Belgravia, you say? Not bad, although I don’t think it’s that much more prestigious an address than ours.”

“Their blue-and-white collection is antique.”

Graham was momentarily silenced. He didn’t pursue that line of thought. “You didn’t tell me you were leaving. I was worried.”

“I’ve returned, so there’s no more need for worry. What did you do while I was out?” Violet heaved her laden bag onto the counter and removed her paintbrush, setting it aside for cleaning later.

Graham picked up the paintbrush. “I’ll take care of this. No customers called. Fletcher stopped in for a visit.”

“Back again with a shipment of rum?” She stowed her bag behind the display counter, making a mental note to refill her bottles of embalming fluid ingredients before her next appointment, in case a customer should actually request the service.

“Yes, he thinks his profits will soon exceed ours.”

Violet laughed. “People may or may not always drink themselves insensible. They will certainly always die. It isn’t a contest between you two, is it?”

She immediately regretted her words. Graham and Fletcher were close, and it wasn’t fair to taunt him this way.

Something else must have been on his mind, for he ignored her comment.

“He showed me this.” Graham proffered her Fletcher’s carte-de-visite, a tinted ambrotype of his brother standing next to a crate marked “Felton’s New England Rum” and holding a conical sugar loaf wrapped in paper. Beneath it were these words:

On the rear of the card was his ship’s docking location at St. Katharine Docks, as well as assurance that his ship, Lillian Rose, was insured by Lloyd’s. In smaller type was the name of the image maker, “Martin Laroche, Daguerreotype Artist, Oxford Street.”

“What do you think?” Graham asked.

Violet returned the card to him. “Impressive. It makes Fletcher appear much more serious about his business.”

“I agree. It elevates him above others. Which is why I think we should have one done.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...