- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

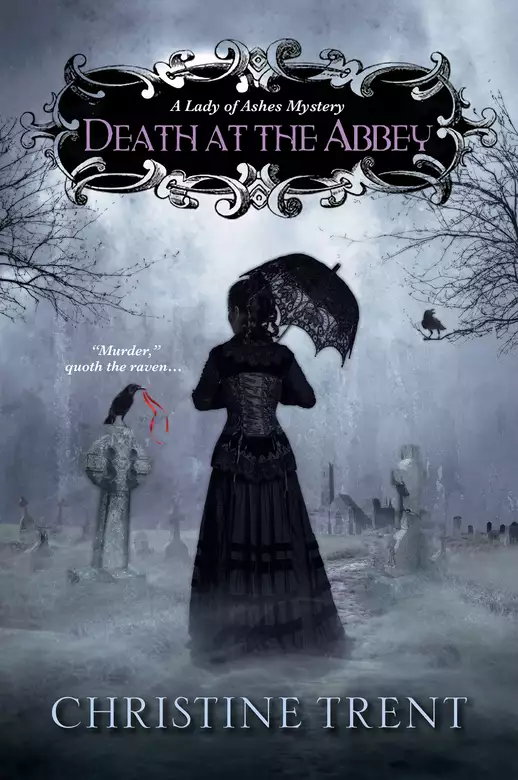

Synopsis

While on a much-needed respite with her husband Sam in Nottinghamshire, undertaker Violet Harper is summoned to Welbeck Abbey by the Fifth Duke of Portland to prepare a body. His Grace is known as the "mad duke," and Violet has more than an inkling of why when she arrives at the grand estate and discovers that the corpse in question is that of the duke's favorite raven, Aristotle. Many of the duke's servants believe a dead raven is a harbinger of doom, and the peculiar peer hopes to allay their superstitious fears with an elaborate funeral for his feathered friend. But Aristotle's demise is soon followed by the violent murder of one of the young workers on the estate. Wishing to avoid any whisper of scandal, the reclusive duke implores Violet to conduct her own discreet investigation. In her hunt for evidence, Violet wonders if the manner of the raven's death might provide a crucial clue in solving the crime. . .before someone else--including herself--risks an untimely fate.

Release date: November 1, 2015

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 290

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death at the Abbey

Christine Trent

All Violet Harper wanted to do was have a peaceful luncheon at Worksop Inn with her husband. Instead, she was summoned away from her half-eaten fish pie to the most magnificent estate she’d ever seen, owned by the most eccentric man she’d ever met, to care for the most bizarre corpse she’d ever been called upon to undertake.

Violet and Sam had been in North Nottinghamshire for almost four weeks, with Violet touring the countryside while Sam worked tirelessly to get his coal mine into operation.

He had leased an abandoned mine that was situated on the Nottingham coalfield, a productive stretch of coal that ran beneath Nottingham. Sam had encountered more difficulties than he’d expected—given that the mine already existed and merely had to be updated and reopened—mostly because of the difficulty in hiring workers. Many locals were already employed at one of the various other active collieries, and a large number of healthy, strapping men worked at Welbeck Abbey, the enormous local ducal estate owned by the 5th Duke of Portland.

Rumor had it that His Grace employed hundreds of workers—not including household staff—for a variety of projects around the estate. But for what, Sam had no idea.

Violet, though, was about to find out, as Portland’s valet stood before her table, as rigid and correct and well groomed as such a servant should be in his work attending to a peer of the realm. The worry lines in his forehead, though, belied his calm exterior.

“Mrs. Harper?” he asked.

Violet put down her fork, which was speared with morsels from the steaming mix of fish chunks, butter, cream, and breadcrumbs, by far her favorite dish at Worksop Inn. In fact, Mr. Saunders, the widowed innkeeper, was kind enough to cook it up especially for her even when it wasn’t part of the day’s offerings.

“I am,” she replied in cautious acknowledgment.

The man bowed and introduced himself as William Pearson, the Duke of Portland’s valet. “Your presence has been much commented upon in town, Mrs. Harper, as your, er, profession is most unusual.”

Very delicately put, she thought, which was surely to be expected from a servant in a high and trusted place, as a duke’s man would be.

“I had no idea my presence was so noteworthy,” she said, hoping the man would finish his greeting and be on his way. Already her fish pie was losing heat, the savory trail of steam from the center opening dissipating quickly.

Pearson, in his correct and formal manner, turned to greet Sam, wishing him well in the formation of his coal mine. Sam’s look of surprise told Violet that he’d had no idea that his activities were already well known in the area.

Unlike in the busy, chaotic world they had recently left behind in London, everyone here seemed to know what everyone else was doing, and they were especially attuned to the arrival and activities of strangers.

Finally, Pearson got to his point, his voice dropping to a nearly inaudible level. “If you will, madam, your services are urgently needed at Welbeck. There is a carriage waiting for you outside. . . .”

Violet was instantly alert, her fish pie no longer of prime importance. “Someone has died at the duke’s home? Was it from an illness or perchance an accident?”

“I’m afraid I cannot say, madam.”

He couldn’t? Or wouldn’t? “What is the person’s age? Is it a man, woman, or child?”

“Again, I am unable to say.” Pearson’s expression was pained. Had something disturbing occurred at Welbeck Abbey? She tried once more as she glanced at Sam, who was shaking his head in a “you’re about to be embroiled in someone else’s problem again” sort of way.

“Has the local coroner been summoned?” Violet asked, which would determine whether the duke thought the death was suspicious.

“Mr. Thorpe is away in Derby, visiting his ailing mother. We don’t know when he’ll be back. In any case, Mr. Thorpe is a civil engineer by way of trade, and what is needed is an undertaker.”

Most coroners were appointed to their positions, often selected for their stature in society—and the major canal, railway, and waterworks projects of the past few decades had greatly increased the reputations of civil engineers. Only rarely was anyone who understood death or human anatomy made a coroner. Violet had often thought that undertakers should be regularly appointed to such posts, but unfortunately, there were enough charlatans in her profession that it did not enjoy a sterling reputation.

“I see. I’ll need my bag,” she said, rising briskly. Reluctantly abandoning her fish pie, but having the good sense to ask the innkeeper to wrap it as an evening snack, she left Sam with the valet and went up to their room to retrieve her undertaking bag—a large black leather satchel containing the cosmetics and tools needed to bring a corpse to the bloom of life. Violet had learned to never travel anywhere without it, precisely for unexpected moments like this.

She swiftly changed out of her burgundy-and-green-striped dress into her regular black crape undertaking dress—clothing she also never traveled without—and grabbed her black top hat with ebony tails from inside the room’s armoire. Once she had tied the hat’s ribbons under her chin and made sure the tails flowed sedately down her back, Violet Harper was thus transformed from carefree tourist to somber undertaker.

“I knew it couldn’t last for long,” Sam lamented as she reentered the dining room twenty minutes later. She typically wore black every day, for she never knew when her services would be called upon, as they suddenly were now.

Violet had largely laid aside the dreary clothing since they had arrived in Worksop. She hadn’t wanted to mislead her fellow tourists at the Long Eaton lace factory or the Sherwood Forest nature walk into thinking she was a woman in deep mourning engaging in entertainments highly inappropriate to such a time.

Sam had daily and delightedly expressed his appreciation for seeing his wife in bright colors for a change. Now here she was, back to her business black.

“It’s just for today,” she assured him.

Sam’s wry glance as he stood to say good-bye suggested he thought otherwise. However, Violet was now too consumed with the thought of the person and unfortunate family who needed her care at Welbeck to be overly concerned about him. The past month had been the longest period she’d gone without preparing for a funeral since becoming an undertaker more than fifteen years ago, except for her interlude of traveling from London to Colorado with Sam four years ago. She had to admit to herself now that she was feeling a nervous tingle at donning her business clothes again and heading off to tend to someone who needed her.

Violet waved absently to her husband and followed Pearson out to the ducal carriage, hoping that whoever had departed had not come to an unnatural end.

As she and Pearson traveled south in the duke’s carriage, Violet surreptitiously took in her surroundings. The conveyance was not only plush and luxuriously outfitted but also remarkably comfortable. Even the royal coronation carriage, as expensive and detailed as it was to carry the monarch, couldn’t rival this one for pleasing accommodation.

“His Grace is very kind to send such a splendid carriage for me,” Violet said to the valet, whose brows were still knit in worry, hoping to coax him into some sort of conversation.

“Yes, the duke is very kind,” Pearson replied absently as he stared out at the fields, now barren of crops for the season.

She tried again. “Our innkeeper tells us that His Grace has many . . . unusual . . . building projects in progress.”

Pearson nodded without looking at her. “He employs around fifteen hundred workers for their construction. That doesn’t include those of us in the household staff, of course.”

Fifteen hundred workers at one time on a country estate! What in heaven’s name is the duke building? A cathedral? Violet wondered.

Their six-mile carriage ride neared its conclusion at a simply marked post indicating the way to Welbeck Abbey, which sent them east down yet another road to the house, which she could already see about a half mile in the distance. Violet was stunned by the level of activity occurring on the grounds before the Abbey, though. It was as if she had slipped through a magician’s fingers from Nottingham’s bucolic fields and forests into a buzzing hive of men and equipment.

Most remarkable were the enormous piles of dirt set amid the backdrop of wooded copses, which were now largely devoid of leaves. Men were busy shoveling the dirt onto wagons attached to what looked like miniature locomotive engines, to be drawn to points unknown. “What is that?” she asked over the din of construction, pointing as delicately as she could at the strange contraption.

“What? Oh,” Pearson said, startled out of his reverie. “That’s a traction engine. It runs on steam and can haul heavy loads more efficiently than horses.”

“Remarkable. And what are the dirt piles?”

“That’s earth removed for the duke’s tunnels, and it will be used to build up the embankments of the lake behind the house.”

“Tunnels? What tunnels?” Violet was thoroughly confused. What need was there of a tunnel on this gently rolling property?

Pearson didn’t reply, and her attention was immediately diverted away as they rolled past the most mammoth oak tree she had ever seen in her life. Not only did it have branches that extended out nearly fifty feet to either side of the trunk—and Violet could only imagine how impressive they were in the summer, filled with bright green leaves—but the main trunk was so extraordinarily large that a passageway had been cut into it.

The duke’s valet, apparently now paying attention, noticed Violet’s awe and said, “That’s the Greendale Oak. It is known as the Methuselah of trees. The opening was cut through in 1724 on a wager made by the Earl of Oxford that a hole could be made large enough for him to drive a carriage-and-pair through it.”

“Remarkable” was again all Violet could manage to breathe.

Pearson nodded. “It is slowly dying, though, from the damage done to it, which isn’t easy to see in the autumn. Welbeck is famous for its ancient oaks. Sir Christopher Wren obtained timber for the building of St. Paul’s Cathedral from this park.”

They were now in full view of the house, which would rival any of the queen’s palaces in size and grandeur, with its three stories of stone jutting proudly up from the ground. Violet imagined it was built in a square around a courtyard, although it was impossible to know from her vantage point. Off to their left was a pair of long buildings that reminded her of a college dormitory. Staff quarters, perhaps?

They passed through a stone entrance gate, which prefaced a wide lawn with identical plantings on either side of the drive. Little was in bloom now, except for some fiery-red dahlias with golden centers and several patches of black adders sporting tall bottlebrush spikes of deep purple.

Before they reached the front entrance of the house, though, the carriage veered off to the right and Violet instantly bristled in annoyance. Did Pearson plan to take her to the rear entrance of Welbeck? It was Violet’s position that she was not a servant but a temporary member of a grieving family, and therefore she always confidently approached the front door of any home of mourning that she was visiting.

The carriage pulled to a stop about halfway down this side of the house, between a lesser entrance and a vast garden, divided up into various squares, each containing different plantings. One square was full of rosemary, sage, and thyme that faintly scented the air. Others were bursting with fall vegetables—broad beans, peas, fennel, sorrel, and tomatoes.

Apples and pears dangled heavily from trees lining the back of these plantings, which Violet realized comprised a kitchen garden. Pearson had brought her to the kitchens? Heavens, she hoped beyond hope that they were not storing the body down here.

Pearson had already stepped out of the carriage with her undertaking bag and was waiting to help her out. She took his offered hand, and exited onto the gravel path. Once again, she had entered another world, as the sawing, banging, and hammering were only distant turbulence from where she now stood. She was pleased that, as horrified as she was at the thought that a body might be lying in state in a duke’s kitchen, at least it didn’t have to endure construction noises.

Pearson escorted her down a set of steps to the basement door, where they were greeted by a heavyset, goggle-eyed, middle-aged woman who was sweaty and breathless beneath her stained apron.

“Mrs. Garside,” Pearson greeted the woman, “this is Mrs. Harper, the undertaker. Mrs. Harper, may I present Welbeck Abbey’s cook to you?”

The cook’s expression was confused, unsure what status an undertaker had, so Violet immediately stuck her hand out to shake the other woman’s. “How do you do?” she said, immediately regretting it because it was the greeting of someone in a higher class, and Mrs. Garside now looked utterly stricken over how to address the undertaker. Violet followed up with, “I’m pleased to make your acquaintance,” and the cook wiped her palm against her apron before taking Violet’s proffered hand.

“Inside, if you please, Mrs. ’Arper,” the cook said in the Nottingham dialect Violet had come to know well. Mrs. Garside stepped back through the doorway and Violet followed with Pearson behind her, still lugging her bag. They were in an anteroom twice the size of her lodgings in Worksop, probably where all deliveries were made so that no visitors could see into the rooms beyond. Violet was instantly struck by the delicious aroma of roasting chicken. Her stomach responded, reminding her that she had regrettably abandoned her fish pie before she’d made serious acquaintance with it. Several doorways led off the anteroom and the hallway beyond, and as they proceeded along the hallway she could see the various rooms necessary for serving a sprawling ducal estate with hundreds of workers: a pantry, a scullery, a dairy room, a pastry room, the main kitchen area, the housekeeper’s room, the butler’s room, and, largest of all, the servants’ hall, where the staff could eat in shifts.

Women in starched aprons and caps, as well as young men in uniforms, bustled back and forth past them, most giving Violet curious glances but too busy to wonder much about the downstairs visitor. Or perhaps they were avoiding Mrs. Garside, who was muttering incessantly that “No good can come upon this ’ouse after this” and “It’s an ’arbinger of more death, I can tell you that much.”

As the cook waddled past the rooms, she was working herself up to the point that Violet thought she might have to intervene to calm the woman.

The farther Mrs. Garside went down the hall, the more relieved Violet felt, thinking that they were going to proceed up a rear staircase to either a bedchamber or dining room, more appropriate locations for a body. Unfortunately, Mrs. Garside stopped before they reached the stairs and turned left into a small room lined with locked glass cabinets painted white. Inside the cabinets were all manner of serving dishes in a variety of patterns.

Violet had no time for scrutinizing the serving ware, though, for it was who was on the table in the center of the room that captured her full attention.

Or, should she say, what was on the table.

Violet was speechless. She turned to Pearson, who had followed her and Mrs. Garside into the room and placed the undertaking bag on the floor. “Surely you don’t mean that I am to undertake . . .” She couldn’t even complete the sentence.

Lying before her on a kitchen towel was . . . a raven. A bird. An ebony member of the avian species. Someone had taken great care to arrange it so that it looked as though it was huddled down to roost. But still, it was an animal, for heaven’s sake! Not even a beloved pet but a wild bird.

Pearson cleared his throat, and looked more uncomfortable than ever. “If you don’t mind, Mrs. Harper, Aristotle was His Grace’s favorite raven—”

“You’ve got to tend to ’im, Mrs. ’Arper, and give ’im ’is proper respects,” Mrs. Garside pleaded, wringing her hands together. “We’re already under the threat of doom because of ’is death.”

Violet took a deep breath and began to compose herself. Surely there had to be a sane explanation for why she had been summoned to a ducal estate to prepare a bird for a funeral. “You led me to believe there was an actual body waiting for me at Welbeck,” she said, turning to Pearson in accusation. She had sacrificed Mr. Saunders’s fish pie and time with Sam for this?

A young kitchen maid about fifteen years old suddenly appeared in the doorway. “Mrs. Garside, I’ve filleted the monkfish for the staff’s dinner like you told me and oh—” The girl’s eyes widened as she realized there were three people crowded around the dead raven’s body.

“Go on now, Judith,” Mrs. Garside instructed. “Dig up some leeks and slice them like I showed you for the fillets.”

The girl needed no further encouragement and scampered right out.

Pearson tried again. “You see, Mrs. Harper, His Grace was concerned by the staff reaction to Aristotle’s untimely demise.”

“Couldn’t someone have merely disposed of the carcass in the woods?” Violet hated to put things so bluntly. She barely restrained herself from adding that undertaking was for humans only.

Mrs. Garside tsked as she shook her head woefully. “Oh, surely you know ’ow a dead raven means death and destruction.”

Whatever was this woman prattling about? “No, I’m afraid I don’t.”

Mrs. Garside eyed Violet suspiciously. “Come now, Mrs. ’Arper, you’re an undertaker. You should know that ravens are the best luck the queen’s got. They’re protected at the Tower down in London, because as long as there’s ravens there, the country won’t fall to a foreign invader. It’s the truth,” Mrs. Garside added, apparently seeing the disbelief registered on Violet’s face. “The ravens ’ave been protecting the Tower since the time of the Conqueror, and there’s been no invasion since then.” She nodded her head firmly one time in emphasis. “Since ’Is Grace keeps a rookery ’ere, it stands to rights that we’ve been protected all these years, but Aristotle’s death is the start of something ’orrible, I just know it.”

“Mrs. Garside,” Pearson said, “perhaps if you could leave us so I might explain to Mrs. Harper the circumstances of Aristotle’s death, she can better care for him and perhaps advise us on how to avoid any further deaths.”

Mrs. Garside nodded with a loud huff. “Yes, Mr. Pearson, I’ll take my leave, but mark my words, the bird is trouble. I’ve a mind to cover the mirrors and stop the clocks.” The cook left the room as she had come in, muttering about other methods beyond mirrors and clocks she could employ to ensure the bird’s spirit didn’t get confused and remain trapped in the kitchens.

Violet whirled on the valet in exasperation. “Why didn’t you tell me in the first place that it was a bird you wanted me to see? This is a task for a taxidermist, not an undertaker. You can hardly expect me to believe that a duke actually expected a dead bird to be prepared for a funeral. I have never—”

“Mrs. Harper,” Pearson interrupted in a low tone, “please allow me to explain. If I had informed you that the deceased was but a common raven, would you have come here with me?”

“Of course not!” Violet was still contemplating a hasty exit back to Worksop Inn.

“No, I suspected as such. However, His Grace wants to calm down the staff, who are nervous and excitable over the idea that a dead raven means a calamity for the household. You witnessed for yourself Mrs. Garside’s agitation. He believes having an undertaker come and conduct a formal funeral will help the staff put it behind them.”

“A funeral! For a raven?” Violet shook her head in disbelief. “Why not just capture another one and add it to the flock? Why the pomp?”

“Because, madam, Mrs. Garside found Aristotle herself, dead on a window ledge facing the kitchen gardens, and it took no more than ten minutes for the rest of the staff to know about it. This is far beyond replacing the bird with another,” Pearson said. Violet wasn’t sure from his tone if he was treating her with the patience he would show to an argumentative child, or if he was shaken by the notion of a curse and trying to convince himself of the validity of what he was saying.

“Please, if you will just tend to Aristotle, His Grace would be exceedingly grateful. He will, of course, pay whatever your charges are for an appropriate funeral.”

What in heaven’s name was an appropriate service for a duke’s dead bird? Was he expecting burial in an actual churchyard? Violet could only imagine that conversation with the local vicar.

Pearson must have seen her wavering, for he pressed his point. “There is something else. I don’t think it is that significant, but you should know that Aristotle was an intelligent bird, and only five years old. His Grace says the bird should have lived to at least twenty years. The Tower ravens are rumored to live up to forty years because of their pampered living conditions.”

There was a problem with Pearson’s claim, though. “Don’t birds frequently die without warning or cause?” Violet asked. “It doesn’t seem all that unusual.”

Pearson acknowledged her question with a nod. “True, but Aristotle has no apparent injuries, and His Grace wants to be certain that nothing untoward happened to him.”

“What of Mrs. Garside’s claim that ravens protect the Tower—and Welbeck Abbey—from foreign invasion?”

Pearson shook his head. “It’s a legend, is all. Started a few years ago by some wag, but now nearly given gospel status. I’m surprised Mrs. Garside didn’t tell you ravens protected Eden, as far back as she takes the tale.”

Violet nodded, understanding how simple rumors, if well told again and again, can become legends. “Well,” she allowed reluctantly, “I suppose that since I’m here, I may as well see what I can do to make Aristotle . . . comfortable.”

Pearson’s relief was palpable as his shoulders relaxed ever so slightly. He thanked Violet, then left her alone with Aristotle.

Violet stared down at her charge, pondering everything the valet had said. What bothered her most was Pearson’s comment that the duke wanted to ensure nothing unfortunate had happened to the raven. Did he actually suspect his prize raven had been intentionally killed?

Violet tapped a finger to her lips, involuntarily shaking her head in disbelief. She wasn’t seriously about to investigate the death of a raven as a murder.

Was she?

Violet was flummoxed as to what to actually do to undertake a bird. She put her reticule down on the table and gingerly ran her hands over the bird’s body and under his wings, feeling for any protuberances or oddities. His feathers were still very sleek and shone almost iridescently. He was quite gorgeous. She gently rolled Aristotle onto his back and ignored his sightless, beady eyes. His talons were curled up and stiff. She’d never thought about it before, but she guessed animals experienced rigor mortis, just like humans.

Out of habit, Violet began talking to Aristotle as she examined him. “Now, sir, you look fine and healthy to me, and I admit I’ve no idea what to do to improve your appearance. I certainly cannot use any cosmetic massage on your feathery face, and embalming is completely out of the question, as I’m afraid it would be too ridiculous. No offense intended, sir. Ah, I see a bit of your . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...