- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

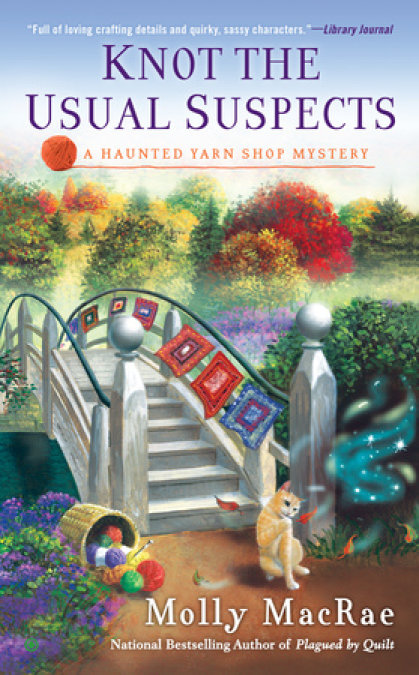

Synopsis

It's time for Handmade Blue Plum, an annual arts and crafts fair, and Kath and her knitting group TGIF (Thank Goodness It's Fiber) plan to kick off the festivities with a yarn bombing. But they're not the only ones needling Blue Plum. Bagpiper and former resident Hugh McPhee had just returned after a long absence, yet his reception is anything but cozy. The morning after his arrival, he's found dead in full piper's regalia.

Although shaken, Kath and her knitting group go forward with their yarn installation-only to hit a deadly snag. Now, with the help of Geneva, the ghost who haunts her shop, Kath and TGIF need to unravel the mystery before someone else gets kilt!

Release date: September 1, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Knot the Usual Suspects

Molly MacRae

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CAST OF CHARACTERS

At the Weaver’s Cat

Kath Rutledge: Textile preservation specialist formerly of Springfield, Illinois, now owner of the Weaver’s Cat, a fiber-and-fabric shop in Blue Plum, Tennessee

Ardis Buchanan: Longtime manager of the Weaver’s Cat

Geneva: The ghost who lives at the Weaver’s Cat, Ardis Buchanan’s great-great-aunt

Debbie Keith: Part-time staff at the Weaver’s Cat, full-time sheep farmer

Abby Netherton: Teenager working part-time at the Weaver’s Cat

Argyle: The shop’s cat

Members of TGIF (Thank Goodness It’s Fiber) and the Yarn Bomb Squad

Joe Dunbar (Tennyson Yeats Dunbar): Kath’s significant other, fly fisherman, watercolorist, sometimes called “Ten”

Ernestine O’Dell: Septuagenarian, retired secretary

Melody (Mel) Gresham: Café owner, calls Kath “Red”

Thea Green: Town librarian who came up with the idea to yarn-bomb Blue Plum

John Berry: Octogenarian, retired naval officer

Zach Aikens: Teenager

Rachel Meeks: Banker

Tammie Fain: Energetic grandmother

Wanda Vance: Retired nurse

Supporting Cast

Shirley and Mercy Spivey: Twins, Kath’s cousins (several times removed)

Hugh McPhee: Bagpipe player, former Blue Plum citizen

Gladys Weems: The mayor’s mother

Olive Weems: Organizer of the arts and crafts fair Handmade Blue Plum, the mayor’s wife

Palmer (Pokey) Weems: Mayor of Blue Plum

Al Rogalla: Accountant, volunteer fireman

Ellen: A knitter in town for Handmade Blue Plum

Janet: A knitter in town for Handmade Blue Plum

Aaron Carlin: Odd-jobs man, significant other of Angie Spivey

Hank Buchanan: Ardis’ daddy

Ambrose Berry: John’s older brother

Angie Spivey: Mercy Spivey’s daughter

Sheriff’s Department

Cole (Clod) Dunbar (Coleridge Blake Dunbar): Deputy, Joe’s brother

Darla Dye: Deputy

Shorty Munroe: Deputy

Leonard Haynes (Lonnie): Sheriff

Chapter 1

Waiting for twilight would have been a good idea. Waiting for full dark even better. A sunny Tuesday morning was hardly the best time for scuttling up the courthouse steps and sliding behind one of the massive columns—not if I wanted to call myself “sneaky.”

I hesitated at the bottom of the steps. My friends and former colleagues back in Springfield, Illinois, might not think so, but from where I stood Blue Plum, Tennessee, bustled. Crowds didn’t jostle me, but in the way of small towns, as long as anyone was around, there was a chance that someone would see something and mention it to two or three others. The problem was partly my own fault. If I’d completed this measuring assignment for TGIF sooner, I wouldn’t have to worry about being surreptitious in broad daylight now. Then again, if we’d included the courthouse in our original plan, I would have had weeks, not days, to get it done. The occasional criminal investigation aside, TGIF (Thank Goodness It’s Fiber—the needle arts group that met at the Weaver’s Cat) was not an organization ordinarily dedicated to furtive operations, though, so I didn’t want to let the others down now, as we prepared for our first-ever clandestine fiber installation event.

The way to sneak successfully, I decided, was to act normal. Eyes open, not casting shifty glances left and right. Shoulders square, not hunched as though ready to creep. Air of confidence. Relaxed smile.

A familiar-looking woman came down the stairs toward me. Her face didn’t jog a name from my memory, but I liked the popcorn stitch cardigan she wore and I smiled as she passed.

“It’s Kathy, isn’t it?” she asked, turning back to me.

“Close,” I said. “Just Kath.”

“I hope you know how lucky you are.”

“Pardon?”

“Lucky to have the Weaver’s Cat. Your grandmother made the right decision in leaving the shop to you.”

“Oh. Thank you.”

“I keep meaning to stop in. Later this week, though. Not today—must rush.”

“Great—” Before I could say anything more, her rush carried her away.

I walked up the dozen worn limestone steps, looking for all the world like anyone else on her way to renew car tags, attend a trial, or probate a will. But at the top, rather than follow an older couple across the portico and through the doors, I stopped, turned around, and pretended to enjoy my elevated view of Main Street.

I didn’t really have to pretend. The streetscape, a mix of mostly Federal and Victorian architecture, looked and felt exactly right to me. Pink and purple petunias spilled from half-barrel planters along the brick sidewalks. Window boxes with red geraniums and sweet potato vines brightened storefronts. Looking right, I saw the bank and half a dozen office buildings and shops and, down at the end of the next block, the sign for the public library. To the left, along past Mel’s café, my own shop, the Weaver’s Cat, basked in the morning sun. This view, this town, had been part of my life through all my childhood summers when I’d come to visit my grandmother in her hometown. Now, thanks to her generosity in leaving me her house and the Weaver’s Cat, Blue Plum was my hometown, too.

I watched Rachel Meeks, the banker, deadhead a couple of geraniums in the planters at the bank’s door. Somewhere in her mid- to late fifties, Rachel’s business suit mirrored her straightforward business sense. Apparently so did her sense of gardening decorum. She carried the withered flowers inside with her. I strolled to the end of the portico, still looking out over the street and assuming I looked casual, then sidled around behind the last column where I’d be in its shadow and couldn’t be seen from the steps or the door. There I took a coil of string from a pocket in my shoulder bag.

A second pair of hands to hold one end of the string would have helped. Unfortunately my favorite second pair of hands had other business that morning. Joe—the Renaissance odd-job-man-about-town who’d worked his way into my heart—had gone over the mountains early to deliver half a dozen fly rods he’d built for an outfitter in Asheville. That was just as well; two of us fiddling around a column would draw more attention. I took a roll of painter’s tape from my bag, tore off an inch-long piece, and pressed it over the end of the string, sticking it to the column at about waist height.

The plan was to circle the column with the string and mark the string where it met itself again, then remove the tape, recoil the string, return string and tape to my bag, and retreat to the Weaver’s Cat. I’d barely started around the column, though, when a familiar voice made me pull back out of sight.

“Ms. Weems, ma’am—oof—now, that was uncalled for.”

“You’re a quack, and I’ll tell anyone who asks.”

“Let’s step on inside, then, ma’am, and you can tell the sheriff.”

I inched around the column in time to see Joe’s uniformed and starched brother, Deputy Cole Dunbar, ushering a tiny, elderly woman through the courthouse doors. The woman, Mayor Palmer “Pokey” Weems’ mother, wore tennis shoes, and it was a good thing. As she passed Joe’s brother, she hauled off and kicked his shin. He winced, but there was no second “oof.” That led me to believe the first “oof” had been a reaction to a different kind of assault—maybe a swift connection between Ms. Weems’ pocketbook and his midsection.

Snickering at someone else’s pain isn’t nice, even if that person is a clod. And even though Cole Dunbar would always be “Clod” to me, I was fairly sure I hadn’t snickered. But before the door closed on him, something made Clod turn toward me and my column. I immediately knelt and retied my shoe, pretending not to notice him noticing me.

“I’m not sure he fell for that,” a voice from farther around the column said.

At one time in my life an unknown and unexpected voice addressing me out of the blue might have startled me. Not anymore. Now I practically yawned to show how blasé I was about such surprises. I also flicked an inconsequential speck of dust from the toe of my shoe to show I wasn’t worried about whether or not Clod fell for my pretense. Then I stood up to see who’d spoken. That I could see a living, breathing human standing there was a plus, even if I hadn’t ever seen him before and had no idea who he was. Judging by the light gray overtaking the dark gray in his beard, I guessed he was in his fifties—older than Clod by at least ten years and Joe by more than a dozen.

“That was one of the Dunbar brothers, wasn’t it?” he asked. “Weren’t they named after composers?” The camera around the stranger’s neck made him look like a tourist. The soft twang in his question sounded local.

“Poets. That was Coleridge,” I said.

“And the other one’s name . . .” He tried to tease it from his memory by tipping his head and waving his hand by his ear.

“Tennyson,” I said.

“That’s it.”

“Coleridge Blake Dunbar and Tennyson Yeats Dunbar,” I said, “except the deputy there goes by Cole and his brother is Joe.”

“Smart move.” The stranger nodded. “Better than Cold Fridge and Tennis Shoe, both of which I remember hearing when the boys would have been at a tender age. Huh. I haven’t thought about them in years. But even back then I wondered how they’d turn out, weighed down with those names.” His tone was mild rather than judgmental. It had a reminiscent, storytelling sound to it.

“You’re from Blue Plum?”

“Not for a few years, anyway,” he said.

Not for a few decades, if he hadn’t known Clod was a sheriff’s deputy and that Joe was, well, Joe.

“Can I give you a hand with your string there?” he asked.

“Oh.” I’d let go of the string when I pretended to tie my shoe. The end was still stuck to the column with the painter’s tape.

“Measuring it for a school project, right? You hold it there and I’ll—” He picked up the dangling end and walked around the column to meet me. “One of my proudest moments in the fourth grade was when I made my cardboard model of the courthouse. Of course, a flexible metal tape measure would be the best way to do this, but your string works, too.”

I took a felt-tip pen out of my shoulder bag and marked the string. He pulled the tape off the column, coiled the string, and handed it to me. “Thanks,” I said, tucking the string and pen back in my bag. “It was nice of you to help.” I turned to go.

And I saw Clod. He’d come back out of the courthouse and stood beside the door in his police-issue posture, arms crossed, watching me and whoever the guy was who’d just helped me with my string-and-column project.

“Hey, Cole,” I called, with a wave as wide and insincere as my smile. “Here’s an old friend of yours.” I pointed over my shoulder, then turned back to my new friend to reintroduce him to his old acquaintance. But no one was there.

Chapter 2

Clod started to say something—possibly Good morning, Ms. Rutledge. Why are you lurking?—but the radio at his shoulder burped static. He listened and responded with a curt, clear “Ten-four” that I imagined spitting out the other end in another eruption of static, intelligible only to the starched and initiated. Without a wave or a nod, he put on his sunglasses and went down the steps and around the corner to where he parked behind the courthouse. I looked around again for the helpful stranger, didn’t see him, and headed for the Weaver’s Cat.

When I’d decided to stay in Blue Plum (due to one thing or another—one thing being the loss of my job as a textile conservator at the Illinois State Museum and the other being the lucky inheritance of Granny’s house and business), Ardis Buchanan told me her secret for getting anywhere fast in our small town. No matter how short the distance, she got in her car and drove. If I walk, she’d said, I’ll run into someone I know, and you and I both know that I am incapable of walking past the opportunity for a good chin-wag. Ardis, longtime manager of the Weaver’s Cat, wise in the ways and means of Blue Plum, was always worth listening to. I’d adapted her solution for bypassing unavoidable chin-wags, taking it in a more ecological and heart-healthy direction. I walked, but I took the less traveled driveways that threaded between some of the businesses on Main Street and the service alleys running behind them.

The electronic chime on the back door of the Weaver’s Cat was another reason I liked taking the alley way to work. The chime—courtesy of my creative friend Joe, né Tennyson, brother of the lamentable Clod—said “Baaaa” every time the door opened. I loved it. Argyle, the cat in residence, liked the chime, too, and he came to greet me in the kitchen, his tail up like a signal flag that read feed me.

“Hasn’t Ardis already given you breakfast this morning, sweet pea?” I asked.

Argyle twined his yellow-striped body between my ankles. I stepped over him, he followed and twined, I stepped, he twined. Together, we moved toward the cupboard that held the dry cat food, doing what I’d come to think of as the “Paw de Deux.” I tipped a few kibbles in his dish, and he thanked me with one last circuit of my ankles.

“She never gives him enough,” a voice grumped from somewhere near the ceiling. I looked up and saw Geneva, the ghost in residence, do a fade-in on top of the refrigerator. “In my experience, young gentlemen require and enjoy unbelievable amounts of what’s good for them.”

I sidestepped Argyle’s thank-you maneuver and looked down the hall toward the front of the shop. Talking to Geneva had gotten somewhat easier in the past couple of months. When she and I had first met, I was the only one who saw or heard her, and communicating openly—without looking or sounding crazy—had presented problems. But now that I’d found a way for Ardis to see and hear her, I only needed to be careful around everyone else in the world. I saw no one in the hall and went back to the refrigerator. Geneva sat with her knees drawn up so that she looked like a wispy gray lump.

“He’s not a young cat, Geneva. The vet says he might be as old as fifteen.”

“When you are one hundred and fifty-nine years old, then you come back and tell me if you still think fifteen isn’t young.”

“But for a cat, especially one who had a rough early life, fifteen is old. The shop is Argyle’s retirement home, and we need to take good care of him.”

She pulled her knees closer and rested her chin on them, a pose that said “hmph” as clearly as words.

“Anything going on this morning?” I asked, watching her body language for further clues about her attitude in general and the current state of affairs between her and Ardis in particular. Watching her “mist” would be more accurate. She rarely appeared more substantial than a film of rainwater on a dark window, or more solid than an Orenburg lace shawl—garments made of lace so fine they can be gathered and passed through the hole in a wedding ring. “How’s Ardis this morning?”

“Hmph.”

“Give her time, Geneva.”

She said nothing and shifted like an annoyed hen ruffling its feathers.

“Would you like me to talk to her?”

“I certainly do not want to talk to her,” she said. “Her happy prattle is like the yapping of a small dog. I find it enervating.”

Oh, brother. Now that Ardis did know about her, communicating with Geneva might be somewhat easier, but dealing with her doleful whims was somewhat less so.

“‘Enervating’ is a very good word, which you can substitute for ‘exhausting,’” Geneva said. “So is ‘depleting.’” With her chin on her knees, she wasn’t easy to understand; I thought she’d said defeating. I was beginning to feel defeated myself. “‘Wearying’ is another one,” she said. “And ‘paralyzing.’”

“Okay. Thanks. I’ve got it.” I spoke louder and sharper than I meant to.

“You’ve got what, hon?” Ardis called as she came down the hall.

“Also ‘dispiriting,’” said Geneva, and she disappeared as Ardis came through the door.

Ardis blinked. “Was that Great-great-aunt Geneva?”

“Hmm, I don’t see her. Maybe she’s up in the study.” I was glad I could sound genuinely unsure.

“But Argyle is down here.”

“Cats and ghosts are a lot alike, Ardis. As soon as you think you see a pattern to their behavior, and you think you can count on it, they figure out that you know, and then off they go and start doing something else completely different. Argyle’s just here having a second breakfast and adding another layer of fur to my ankles. Geneva’s probably off having her morning alone time.”

“The morning alone time—is that a pattern you’ve noticed?” Ardis asked.

“Not so much a pattern as . . .”

“As what? I keep feeling as though I should be taking notes.” She patted her pockets for the pencil she’d stuck behind her ear.

“Alone time isn’t so much a pattern as something she seems to need a lot of.”

“Ah.” Ardis nodded, looking solemn. “It’s what she’s used to, isn’t it. She hasn’t known much else for the last hundred and twenty or thirty years and it might be hard to adjust.”

“Alone time punctuated by a regrettable decade or two of nonstop television.”

“But that wasn’t in any way her fault,” Ardis said, “and her addiction is understandable. And under control, too, wouldn’t you say?”

I held my hand out and tipped it back and forth.

“Well. I’ll let her have her privacy.” She stooped to rub Argyle between his ears, making it look as though that required all her concentration. Then, sounding wistful, she asked, “Have you seen her today?”

“For a minute or two. She seemed tired.”

“Is letting her have alone time enough, then? Is there anything else I can do for her? I mean, after all these years, to find each other, it’s nothing short of miraculous. Odd, too, what with me, the great-great-niece, pushing seventy and her, the great-great-aunt, stuck in her early twenties. But the whole situation is miraculous. You see that, don’t you?” She didn’t wait for an answer. “I’ve been making a list of questions to ask her. After she gets better used to me, of course. That’s the best plan, don’t you think?” She was entering into the small-dog phase Geneva objected to.

“Give her time, Ardis. And space.”

“It’s all pent up, though. The questions and . . . everything.” Her eyebrows inched up her forehead, as though illustrating the increasing level of things pent up. “And it’s been weeks since she and I met each other on that wonderful, amazing day. More than a month. Closer to two. And I still don’t always see her, if you know what I mean. I can’t always bring her into focus, which is so frustrating.”

Ardis fiddled with the braided bracelet on her wrist. I’d made it for her, using cotton warping thread I’d dyed with one of Granny’s recipes. The bracelet wasn’t anything fancy or stylish, although it was a lovely grayish green and I’d done my best not to make it look like a summer camp arts and crafts project. But the bracelet did have an interesting quality. Thanks to following the recipe my grandmother had called “Juniper for Long Lasting and Friendship”—which came from dye journals she’d kept secret and then left to me—the bracelet somehow let Ardis see and hear Geneva. Whether it would let anyone who wore it see her, or if the bracelet only enhanced a connection between Ardis and Geneva, I didn’t know. That it worked at all was astounding and weird and messed with my science-oriented mind. But, for better or worse (and lately for grumpy and disheartened), it brought my two odd friends together.

“I’ve never asked you how the bracelet is involved—”

I held a hand up and she stopped.

“I understand,” she said. “Don’t ask, don’t tell. I just wondered if something is, I don’t know, wearing off?”

That was a possibility, I guessed, but because I didn’t really understand it, either . . . “Do you hear her or see her any less clearly than when you first wore the bracelet?”

“No, and that’s why I keep hoping that if I can talk to her, engage with her more, then the focusing problem might improve. Was that your experience with her?” She stopped and looked at me and gave a frustrated cluck. “It wasn’t, was it. Do you wear something?”

I shook my head.

“You must have a natural talent for this, then. For ghosts. You and Ivy.”

My “talent” for ghosts was something else I’d inherited from Granny—Ivy McClellan—along with the shop, her house, the secret dye journals, and another “talent.” The other “talent”—more a “glitch” to my mind—let me feel a person’s emotions if I touched a piece of clothing. It didn’t always happen, I didn’t understand it, and the jolts I received when it did happen made me think twice about casually patting strangers on the back. The dye journals and “talents” had come as an unexpected bonus after Granny died. Or, as Geneva might say, “unexpected” and “bonus” were words that, when combined, made a good substitute for “wow, I did not see that coming.”

“What should I do?” Ardis asked. “You know Geneva so much better.”

“Please believe me when I say I still have a lot to learn, Ardis. Beyond time and space, I don’t really know. But time and space can’t hurt.”

“I know. You’re right.” She folded her hands, holding them tightly in front of her, keeping pent-up things in check. “I’m trying.”

“She’s dealing with so many different emotions and her situation has changed so drastically in the last seven or eight months.”

“I know. And more so recently. She’s like some of the kiddos I had in my classes. The ones from ‘complicated home situations.’ That’s how we described those situations when we wanted to be polite. There was so much you wanted to do for the little buttons and so much that no end of doing would ever fix.”

“That’s a good analogy, Ardis. Geneva’s pretty resilient, though.”

“Most of the kiddos were, too.”

Ardis wouldn’t have liked the comparison, but she and Clod adopted similar poses when they had serious matters to think over—pursed lips, drawn brows, gaze fixed on the floor. They were also both six feet tall—a height not unusual for a man, but imposing in a seventy-year-old woman with the steely nerve of a former elementary school teacher. Especially such a woman who also relished standing toe-to-toe or nose-to-nose with stubborn authority. And Clod was born to be upright and mulish.

“Maybe if I run upstairs and let her know I’m here for her,” Ardis said. She looked up the back stairs, in a way that could only be described as longingly. The study was in the attic, two flights up, and Geneva and Argyle spent at least part of each day hanging out up there. “So she knows she can come to me anytime.” She put a hand on the banister and a foot on the bottom step, her instinct to mother giving a strong tug.

“That’s a nice thought—” I was going to add a “but” to that statement when the string of camel bells jingled at the front door, doing it for me.

“I’ll go,” Ardis said, her business instinct and dedication to customer service winning out.

“Thanks, Ardis. I’ll put my purse away and be with you in two shakes.”

“But before I forget, and at the risk of being a nag, did you get the last measurements?”

I clicked my heels and snapped a salute. “Yes, ma’am. We are all set to bomb the Blue Plum Courthouse.”

Chapter 3

“Excellent.” Ardis rubbed her hands. “We shall continue to keep mum while the knitting public can overhear us, but, may I just say, I can hardly wait for Thursday night?”

“It’s going to be a blast.”

“Utter,” Ardis said, “and absolute.”

She trotted down the hall to the front room and Argyle joined me for the trek up the back stairs. Despite what I’d told Ardis about the ever-changing habits of cats, Argyle’s nap schedule didn’t have much room for variation. Nap time called frequently and often, and the window seat in the attic dormer was a favorite place. He leapt onto the cushion now and curled into a skein of snoring yellow fur. I took the coil of marked string out of my shoulder bag and tucked it in a pocket. The bag went in the bottom drawer of the oak teacher’s desk.

The study had been Granny’s snug and private space. Now it was mine. Except that I shared it with Argyle and Geneva, and that made the snug space . . . snugger. Granddaddy, as creative in woodworking as Granny had been with fibers and fabrics, finished the wide-plank floor, fitted bookcases and cupboards under the eaves, and built the window seat in the dormer. He’d also hidden a tall, narrow cupboard behind one wall. He’d painted the inside of the cupboard Granny’s favorite deep indigo blue and printed MY DEAREST, DARLING IVY along the edge of the shelf he’d put in the cupboard. Granny had kept her private dye journals on that shelf. Geneva claimed the cupboard as her own “room.”

“Geneva?” I called.

“Boo.”

I turned around. She was floating behind me.

“You do not jump as much as you used to when I sneak up on you.”

“Have you been up here since you disappeared in the kitchen?”

“I sat on the stairs while you talked to Ardent. That is what her name means. Did you know that? And that is what she is, too. Putting up with Ardent is arduous.”

“I asked her to give you time and space,” I said. “Do you think you can be more patient with her? This is a new situation for both of you. And you’re right; she is ardent. But she’s tickled pink that you’re here and that you’re her great-great-aunt.”

“Her great-great-aunt who has never liked the color pink.”

“Come on, Geneva. It really would help me out if you two could meet each other halfway.”

“On the stairs? I do not think her creaky old bones will be comfortable sitting on the stairs. I did not get where I am today by having creaky old bones.”

I was feeling enervated and didn’t say anything.

“That was haunted humor, in case you did not notice.”

“I’ll come back when you’re ready to take this seriously,” Geneva said.

“But you cannot tell me you did not cringe when she started prattling.”

“She’s excited. You get the same way when you’re excited. You two are a lot alike. I’m kind of surprised I didn’t notice that sooner. Come on, Geneva. You heard her say she’s willing to give you time and space. There need

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...