- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

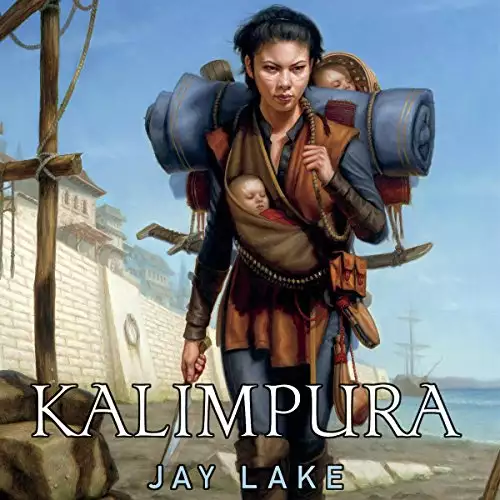

This sequel to Jay Lake's Green and Endurance takes Green back to the city of Kalimpura and the service of the Lily Goddess.

Green is hounded by the gods of Copper Downs and the gods of Kalimpura, who have laid claim to her and her children. She never wanted to be a conduit for the supernatural, but when she killed the Immortal Duke and created the Ox god with the power she released, she came to their notice.

Now she has sworn to retrieve the two girls taken hostage by the Bittern Court, one of Kalimpura's rival guilds. But the Temple of the Lily Goddess is playing politics with her life.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: January 29, 2013

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Kalimpura

Jay Lake

I HAVE RARELY recalled my dreams, not in those years of which I now tell, nor since. I do not know why this should be. Life has perhaps always been so vivid, so overwhelming, that the far countries of sleep pale by comparison. How can a dream offer more than the simple richness of a mug of kava whipped with cream, cinnamon, and red pepper? How can the illusions of the sleeping mind overwhelm the feel of the wind on one's face as dawn paints the eastern sky in the colors of flame and life, while the first birds of morning leap to the air in their chattering hordes?

Yet during that last month or so of my pregnancy, I had been dreaming as never before. Even now I recall my extraordinarily vivid awareness of life beyond the gates of horn at that time. I awakened time and again in the tent that my old friend and Selistani countryman, the pirate-turned-priest Chowdry, had made my own out of his concern for me. Swollen and awkward from the babies in my belly, I was barely able to waddle in order to break my fast amid the overgrown children who labored to build this new temple to this new god Endurance whom I helped create. Those last weeks of my pregnancy were certainly the dullest of my then-sixteen years of life.

Perhaps it was thus that the dreams came to prominence.

Not for me visions of the face of my long-lost father, ancient wisdoms dripping from his lips, as I have heard others tell. Nor the refighting of old battles. Little enough, judging from the books I've read that speak of such signs to be found in the night mind. Instead, my dreams had been of heaving oceans and sheets of flame leaping to the sky. Ships and burning palaces and always I ran, looking for those whom I have lost. Always I begged and swore and promised I would never again do wrong if only I could set right what had been overturned in my careless haste.

Dreaming, in other words, of what was real. A girl and a young woman lost as hostages borne across the Storm Sea. The girl is Corinthia Anastasia, child of Ilona whom I loved though she did not love me the same in return, stolen away by my enemies as a hostage to my future good behavior. Likewise the Lily Blade Samma, my first paramour from my days in the Temple of the Silver Lily. Those two, each dear to me in different ways, were being held to bind me to the will of Surali, a woman high in the councils of the Bittern Court back in Kalimpura.

In short, I awakened not from prophecy, but from memory.

And now my belly hung empty. Two tiny mouths gnawed at my breasts, which I swore belonged to some stranger. I was never pendulous, nor did my nipples weep before childbearing. There was little about pregnancy consistent with dignity. Motherhood had not begun much better.

If there had been a blessing of late, it was that the gods and monsters who haunted me stayed away from both my dreams and the waking moments between them. Somewhat to my surprise.

My children were my own. None of the prophetic threats made for them had come true.

Not then, in any case.

"Green?" Chowdry lifted the flap of my tent, though he did not peer within. "It is almost time."

"Thank you," I said. "When the children are done suckling."

"I will send Lucia."

Lucia? I thought. My favorite acolyte of late, and sometime bath-and-bed partner. How odd that Ilona did not claim for herself the joyous task of dressing the babies this of all days.

Chowdry withdrew, leaving me alone in my bed with my children. The little iron stove smoked a bit—spring had come to Copper Downs, but here in the chilly northern realms of the Stone Coast, that did not necessarily mean warmth. Bright-dyed hangings decorated the wool-lined canvas walls. Two chests, one lacquered orange in the Selistani fashion, the other a deep, rich mahogany, held my worldly goods along with what was needful for the babies.

Almost I could fit into my leathers again. That thought brought me immense cheer.

Lucia bustled in. She was a beautiful Petraean girl, her skin as pale as mine was dark, though we shared the same golden brown color of our eyes. It was something of a scandal around the Temple of Endurance that she had been an occasional lover of mine, before the last stages of pregnancy had forced me to give such up. I think she would have played nursemaid to my children every day, but Ilona was letting no one else near them for anything she could do first.

Her need for her lost daughter was so profound, and my responsibility in the matter so deep, that I could deny her nothing with respect to my children.

"Will you be ready soon?" Lucia smiled fondly. "Ilona is desperate to be in two places at once right now. Chowdry has convinced her to finish preparations in the wooden temple."

"And so she ceded her care of the babies to you." I found myself amused, though I realized that was unkind of me.

"All of them dressed and ready," Lucia said in a fair imitation of Ilona's voice. "And mind you don't forget the rags!"

I had to laugh at that. My girl shifted from my breast and mewled some small complaint. "Help her spit," I told Lucia. "I'll get the boy to finish."

It is the custom among the Selistani people of my birth not to name children until they reached their first birthday. The world was filled with demons, disease, and ill will that might be called to a weak, new child if their name were spoken aloud. Here in Copper Downs as all along the Stone Coast, I was given to understand that children were generally named at birth.

Having been born a Selistani but raised among the people of the Stone Coast, my compromise was to allow my babies to pass their first week in anonymity, then name them. Regardless of which practice I chose to follow, no child of mine would ever be safe. My list of enemies was longer and more complex than I could keep an accounting of. Some of the most dangerous among them even considered themselves my friends.

Besides, their father, my poor, lost lover Septio of Blackblood's temple, was Petraean. To name the babies was to honor him.

Lucia hummed and bustled with my girl, wrapping the little one in an embroidered silk dress that would serve for the Naming, even if the baby should do any of the things babies so often do to their clothing. I separated my reluctant boy from my aching right nipple and briefly hugged him close to my shoulder.

The love I felt for them was foolishly overwhelming. I knew it was some artifice of nature, or the gods who claimed to have made us in their image, for a mother to adore her child so. Otherwise no one sane would tolerate the squalling, puking, shitting little beasts. But I did love him and his sister with an intensity that surprised me then and continues to do so to this day.

It was akin to the sensation of being touched by a god—an occurrence that I had far more experience with than I'd had with the demands and requirements of motherhood thus far.

I sat up. The boy lay above my breast against my shoulder. My gut continued to feel empty, weak and strange. I would not care to be in a fight for my life right now. Soon enough I would be able to work my body as I was accustomed to doing. I scooped up a rag and gently dried my sore nipples. Lucia leaned to take the baby from me so I could clothe myself.

"Thank you," I told her.

Her eyes lingered on me. I had not dressed at all yet, still naked as birth or bath required. "You are welcome." Her smile was warm, welcome, and just a little bit wicked. "It is nice to see you more yourself again."

I took her meaning exactly and felt warmed for it. Definitely time for me to dress. Though it was very much not the fashion for women of status here in Copper Downs, I was still most comfortable in trousers—my midsection felt a bit better supported, somewhat more firmly held in. The pale blue silk robe would hide the pants well enough. Not that I cared so much what people thought, but that would reduce the potential for argument and satisfy the sense of propriety shared by various of those around me.

Somewhere in the recent months, getting along better with people had started to become important to me. Troubling myself with the opinions of others was still a new experience.

I strapped my long knife to my right thigh beneath the robe. My short knives I secured to my right and left forearms. I truly did not expect any sort of fight at this ceremony, and was not in much shape to join in if one were to take place, but they were part of me. Bare skin would feel less naked to me than going into public without my weapons. I had birthed my children with a knife at my hand, after all.

Lucia had both the babies ready. My girl was in a fall of flame orange and apple red silk that ended in a ruff of yellow lace. The needlework across her bodice was a vibrant, bleached white that stood out like the Morning Star. My boy's dress matched in cut and design, but was sea green and sky blue with a ruff of violet lace, embroidered in a blue so dark, it was very nearly nighttime black.

They were beautiful.

I stared into their strangely pale eyes, those unfocused infant gazes looking back at me. Though Lucia had one of my children balanced in each arm, they knew their mother.

My heart fluttered and my entire body felt warm. My breasts began to swell, which was not what I wanted. Not more milk, not right now.

I shrugged my careworn belled silk over my shoulders, then took my daughter's new silk in my hands to cradle her at my left. Her bells were so few and small that it hardly made any noise at all. Still, this custom was all I had of my grandmother and the family of my birth—the single memory of her funeral, the sound of her bells, and the constancy of my own bells.

Prepared now, I reached for my girl, then for my boy, who would have to find his way in the world without the protection of a cloak of belled silk. The four of us left the tent. As I stepped through the flap, I wondered anew how Chowdry had convinced Ilona to allow Lucia this duty. She had been by my side almost continuously since the birth.

The kidnapping of Ilona's child by my enemies hung over the two of us like a shadow. Or a blade, twisting by a fraying thread but yet to drop. That thought dimmed the glow in my heart a bit.

* * *

Outside was brisk. Spring might have been there, but the sun had not yet found her summer fires. Not in this place. Still, no one had told the trees and flowers. The brisk air was rich with scents of bloom and sap and leafy green.

The Temple of Endurance was blessed with high walls, thanks to an accident of location. This site was an old mine head, long since hidden away from view or casual trespass. Beyond those walls was the relatively clean, quiet wealth of the Velviere District. That meant here inside the compound we were spared the worst of the reeks that emanated from the sewers, slaughterhouses, fish markets, and middens of Copper Downs. In fairness, distant, tropical Kalimpura brought a whole new definition to a city's smells, but even the wrong district here on Stone Coast could put out a standing reek fit to stop a horse. I was glad of the air being washed with spring and nothing more for this Naming.

Beyond the line of tents, a scaffolding rose around the stone temple under construction. I'd helped a little with laying out the foundations before the last months of my pregnancy. Since then, Chowdry and his congregation had made great progress without my aid. Endurance was well on his way to having a permanent fane here in Copper Downs. Pillars rose, and wooden forms were being hammered together to support the laying of a grand vault.

So odd, such a distinctively Selistani god here so far from home. And entirely my doing. Even more odd, this was the first new temple built in over four hundred years, thanks to the late Duke's centuries-long interdiction of such activity. The lifting of his rule was also my doing, in point of fact.

We walked slowly toward a chattering crowd surrounding the wooden temple, the music of my silk ringing out our every step. This was the small, temporary place of worship, in effect a glorified stable built around the ox statue that was Endurance's physical presence here amid his worshippers. Both dear friends and total strangers awaited us. The acolytes and functionaries of Chowdry's growing sect were naturally in attendance. But also a few familiar faces from the Temple Quarter, and the women's lazaret on Bustle Street. Several tall, pale young men who were surely sorcerer-engineers on a rare venture into sunlight. Even some of the clerks from the Textile Bourse, home of one of this city's two competing governments struggling through a slow, apparently endless round of ineffective coup and countercoup.

Most important, Mother Vajpai and Mother Argai awaited me. Senior Blade Mothers from the Temple of the Silver Lily in Kalimpura, and Mother Vajpai one of my two greatest teachers, they had been stranded here by the betrayals of Surali of the Bittern Court when the Selistani embassy had come to Copper Downs the previous autumn. The Prince of the City had ostensibly arrived on these cold northern shores in pursuit of trade agreements, but he had really been brought across the Storm Sea to serve as the Bittern Court woman's puppet in a far more convoluted series of plots. These two lonely Blades so far from home were the closest I had to family anymore. In many ways, these women knew me best.

I smiled at them all, warmed even by the pallid sunshine of this northern place, and walked slowly toward the plain doors of the wooden temple. The crowd parted around me like a pond confronted by a prophet. The babies gurgled, enjoying the outing it seemed, and without fear of the people.

May they live a life free of fear, I prayed to no one in particular. I had too much experience of gifts from the gods to want any of them to hear me just now. Besides, twinned prophecies had hung over my children's birth. Both could go forever unfulfilled for all I cared.

At the door to the wooden temple, I paused and turned to the crowd. Dozens of faces stared back at me. Joyous. Friendly. Loving, even.

It was such a strange feeling, to witness this outpouring.

"My friends," I began. My son shifted in my arms, responding to my voice. He could not know this young that those simple words that were at once so inadequate and yet so true. "We are drawn together this day in celebration." I sounded foolish to my ears. Like a tired priest lecturing an even more weary congregation. I summoned my courage and my sense and continued. "My children are my life. My life is yours. Thank you."

With that, I rushed into the shadows behind me.

* * *

At that time, the temporary wooden temple was still little changed from the first occasion on which I had visited it. The beaded curtain on the doorway stroked me with the caress of a dozen dozen fingers. The walls held their same roughness, though prayers had been hung upon them. Brushwork in dark brown ink on raw linen, written in both Petraean and Seliu, they had the same beauty as those Hanchu poetry scrolls one sometimes sees decorating great houses.

Endurance was present in the form of a life-sized marble sculpture of an ox. His blank-eyed calm was soothing to me. Tiny prayer slips still dangled by red threads from his horns, but the usual array of incense, fruit, and flowers had been cleared away. Instead, I saw a line of offerings fresh from the bakeries and groceries of the city. Food still warm and crisp, the odors from the bread and nuts and, yes, more fruit, joined to form a lovely incense of their own. It was an offering for the eyes and nose and mouth all at once. I hoped Chowdry would allow the array of food to be eaten later.

The reluctant priest waited by the ox with Ilona. They were the only people in the wooden temple when I entered, though others pushed in behind me, led by Lucia carrying my girl. Chowdry wore a green silk salwar kameez that I'd never seen before. Ilona had found an orange silk dress that recalled the cotton dress of hers I'd loved so much back at the little cottage in the High Hills.

The two of them smiled, proud as any grandparents. I was pleased that Ilona did not feel the need to bestow her usual frown on Lucia. Not jealousy, precisely, but the two of them disagreed so much over me.

Holding both my children close, I advanced jingling toward Chowdry and Ilona. The jostling crowd behind me maintained a respectful silence.

"Who comes before Endurance?" Chowdry asked formally.

Resisting the urge to say, Me, you idiot, to this man upon whom I had bestowed both a god and the mantle of priesthood, I answered in kind. "Green, of Copper Downs and Kalimpura, to present my children to the god."

He swept his hands together and beamed as if delighted by some strange and wonderful surprise. "Be welcome, and come before the god."

Chowdry stepped to one side, Ilona to the other. Her face was troubled now. I knew why. My old would-be lover could hardly help thinking of her own daughter stolen away. With the heft of a baby in each of my arms, I was all too aware of how keenly Ilona missed Corinthia Anastasia, mourning her child's absence.

I have not forgotten my promises, I thought fiercely, willing her to hear the silent words from behind my eyes. Then I was before the god I myself had instantiated from a flood of uncontrolled divine energy, naïve hope, and my own earliest memories.

Kneeling, I placed my children against his belly. Had the artist sculpted him standing, I would have laid them between Endurance's feet as I myself had once played and sheltered beneath my father's ox. This was the best I could do.

Then I touched one of the horns. A few of the prayers tied there stirred, so I brushed my fingers across them. Whatever power or influence I had with the divine I put to wishing the prayers might be heard.

"I am here," I told the ox.

Now all the prayers on his horns stirred. The air felt thick, even a bit curdled. Something was present.

"I know you will not answer me. That is not your way." Endurance was a wordless god, given to guidance through inspiration rather than immediate intervention in the lives of his followers. "But when I was a small child, you watched over me. Your body sheltered me. Your lowing voice called me back from danger. You followed where I wandered, and led me home again."

I paused for a shuddering breath, wishing in that moment that my father could have seen this time of my life. He would have been delighted at his grandchildren, I was certain of it. And amazed at what had become of his ox. That, too, was certain.

"Watch over these children of mine, so new to the world. They do not know its risks. Shelter them. Let them wander, and call them back from danger." In a rush, I added, "Also, please watch over Samma and most especially Corinthia Anastasia, for they are in grave peril, needing of shelter, and surely wish more than anything to be called back as well."

I touched my girl. She gurgled, bubbles forming on her lips, and stared up at the curving flank of the ox god with the myopic expression that all new babies seemed to share. "This girl-child I name Marya, to honor a goddess slain unfairly, and through her, to honor all women."

Behind me rose a muttering. People didn't like that name so much. Marya had been a woman's goddess, her name unlucky now after her demise, though I had avenged her deicide. These grumblers could fall on their own blessed knives. I was hardly going to name this child Green after me, given that my own name was a product of my enslavement.

I touched my boy. He didn't bubble or coo, but rather turned his head toward me with a gummy, toothless smile. "This boy-child I name Federo, to honor a friend who died badly but bravely, his entire being possessed by godhood. And to honor the fact that nothing in my life would be as it is today without him. For good or for ill."

That name raised a greater hubbub behind me. Federo had very nearly been the death of so many of us. But he was who he had been to me—the man who had bought me from my father as the smallest of girls, fostered my secret training to slay the late, unlamented Duke, protected me, before turning on us all when he was corrupted by divine power. Everything and nothing, enslaver and redeemer both. But in the end, he was just another of my kills, and a city's-worth of trouble had come with that deed.

Careful of my balance and of their fragile little necks, I collected my children and turned to the crowd of well-wishers. "I give you Marya and Federo," I called loudly enough for my voice to ring within the confines of the wooden building. "May they live long and happily under the protection of Endurance."

That provoked a round of applause that was most pleasing to me. People pressed forward to touch the children, to touch me, to push gifts upon the three of us. I did not like this so much, but I understood it to be inescapable, at least not without deep gracelessness on my part.

So I smiled and let my children be welcomed into their lives.

* * *

Ilona had helped me back to the shadows of my tent. The brazier within was warm. I'd grown chill outside, and worried that the babies had as well. Their two little cradles were already drawn up before the potbellied brass heater on its curled-out chicken legs. Someone had placed chips of sandalwood on the fire. The scent was soothing.

My breasts ached again, and the children were fussing. I figured they would suckle a short while, then go down to nap. Both at the same time, if I were lucky. I was already learning what a trial twins could be.

"Let me hold Marya," Ilona said. "You care for Federo first."

I heard the pain in her voice. "If not for Federo, we would never have met," I reminded her. Fleeing from his army, wounded and exhausted as I'd stumbled through the unfamiliar High Hills leagues north and inland of Copper Downs, I had been taken in and sheltered by Ilona and her daughter.

From that, so much had grown between us. I wished then and sometimes wish still that more might have grown between us. How different my life would have been.

"If not for Federo…" She couldn't finish articulating her thought, though the words were clear enough to me.

"If not for Federo, Corinthia Anastasia would yet be with you. And your little house would still stand unclaimed by fire." I slid out of my belled silk and my fine dress, pulled on a quilted cotton jacket that I left open, and settled little Federo into my breast—one privilege his adult namesake had never tried to claim from me, to the man's credit. Looking up, I caught her eye and willed the haunting I saw in there to fade like darkness at dawn. "I know your pain, Ilona. And I will set it right."

"No, Green. May you never know my pain." She clutched little Marya so tightly that I briefly wondered if this was a threat. I was certain that Ilona had never trained to be a fighter, but a woman who'd lived alone in wild country as she had for years was dangerous enough in her own right.

"I have dreamed, over and over, of finding them. If I could run across the wave tops, I would already be gone." My own words captured my imagination a moment, boots from some magic cavern out of a child's tale that might take me from crest to crest in strides of a dozen rods per pace. I could feel how the wind would pluck at my hair, how the storms would dog my back without ever catching up to me.

"No one runs the waves except in a boat."

"Ship," I said absently, wincing as Federo sucked overhard. For a child with no teeth, he could chew far too well. "And I have crossed the Storm Sea three times already in my life."

Ilona looked down at Marya. "You cannot take the children with you."

There she touched on what had rubbed me hardest these past weeks. I had thought much about this exact question. "I cannot leave them behind," I said gently. "They would be … well … claimed. They would be claimed by others." Oh how true that would have been; I knew it then and still know it now all these years later.

"You stand too close to power." She laughed, though there was no mirth in her voice. The joy of the Naming had leached from me as well, I realized. "The gods will strip you naked and bloody, and all you will get in return is a demand for more."

The way she said that gave me a moment's pause. After considering why, I spoke. "I have never seen you pray. Or lay out an offering. And you came of age under the Duke, when the gods here were stilled."

"There are many voices in the High Hills." Ilona stepped toward me and helped me switch the babies. "Not all of them boom from the grave," she added as we completed our efforts.

She'd never spoken of her past, not between the time she'd left the Factor's house and when I'd met her living in the cottage tucked within the feral apple orchards. Who had fathered Corinthia Anastasia, for example? How had Ilona come upon the trick of listening to the ghosts?

I'd just been handed a hint. Huge and painful and difficult, and one I could not pursue now. Would not, for love of her.

"There are many voices in this world," I said gently. "As you said, not all of them boom from the grave. We will find your daughter, and we will bring her home. This I swear on the lives of my own children."

"Don't." Ilona's finger touched my lips. I shivered at the caress, though she meant nothing so intimate by it. "Do not make me promises you will not keep."

Stung, I replied, "I keep all my promises." But even in those days, I knew that was not true. Such a thing could be true of no one except she who was a miser of her spirit and never promised anything at all.

Ilona's eyes glittered with unshed tears as she walked away. Carefully I put the babies down in their cradles, then took up my knives and went out into the cold. My body might not be quite sufficiently healed for the work of readiness, but I could not deny it.

Besides, I needed to do something with my rage before someone else came along and stumbled upon the brunt of it.

* * *

I chopped again at the wooden man I had lashed together from beams and stakes. Chips arced away from me into the weeds. This was wrong of me—bad for my blades, bad for my own form, wasteful of the wood—but I needed to cut, and cut deep.

Everything ached, not just my breasts and loins. Muscles in my back and legs screamed their protest after long disuse. My arms burned with the exertion. My eyes burned with tears.

Trapped. So damned trapped. I had only one course open to me, and it was impossible for me to follow. How could I take the babies across the Storm Sea? How could I leave them behind?

Another flurry of blades and blows, and stinging pain to my wrists as metal bit wood. I imagined Surali's face before me, cheekbones crushed under my assault, eyes bleeding, lips spread wide by the slash of my knives. The architect of all my troubles, she was a human woman as confounding to me as any god had managed to be.

I drove my long knife into the target so hard the blade sang as if it would break. A rope snapped, bits of hemp flying off in the air as the wooden man collapsed. Embedded, my blade went with it. I would deserve the trouble it would cause me if I'd broken the weapon.

"Feel better?"

Whirling, I confronted Mother Argai. She'd spoken in Seliu. Even after months here in Copper Downs, her Petraean vocabulary was largely limited to coinage, drinks, and cursing.

"What?" I demanded, feeling as clumsy with my words as I had been with my weapons.

There was no watching crowd. My bursts of rage and energy were well known now. Even Lucia had not followed me out past the temple foundations to watch me scramble among the weeds and piled dirt. Only Mother Argai, her face quirked into a curious expression.

"What, indeed," she said softly. "What?"

"I don't know," I confessed. Now I was ashamed of my mood. Anger was not power. It was just anger. A disease of the soul, if one indulged the emotion overmuch.

Mother Argai sat on my broken pile of wood. "What don't you know? What it is you should be doing?"

"Oh, I know that. We return to Kalimpura."

"When?"

"As soon as…" As soon as what? When the babies were ready? When I was ready? My voice was small and shamed as I finished my thought. "As soon as I am able."

"Breaking weapons does not increase the likelihood of you being able." Her tone was mild, but I could hear the scorn as she tugged my long knife free of a shattered baulk of timber and flipped it toward me.

That was an old Blade teaching trick. Throw a weapon at a student and see what they did. Most people needed stitches only once or twice.

Not me. I'd never been cut that way. I snatched the spinning knife out of the air, whipped it against my forearm to sight down the edge, then sheathed it. "A dull blade."

"And you?"

A dulled Lily Blade, of course. I'd stepped right into that bit of rhetorical trickery. "We are going," I told her. "As soon as I can arrange passage. Will you inform Mother Vajpai?"

I had missed being so decisive. This was as if I'd woken up from a longer sleep than was reasonable.

"If you wish," Mother Argai said quietly. "She has gone back to rest." The amputation of Mother Vajpai's toes at Surali's orders was one of the many sins I held higher than the value of that wretched woman's life. "What of your friends and enemies here?"

"For the most part, they are the same people." I snorted. "Still, you ha

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...