- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

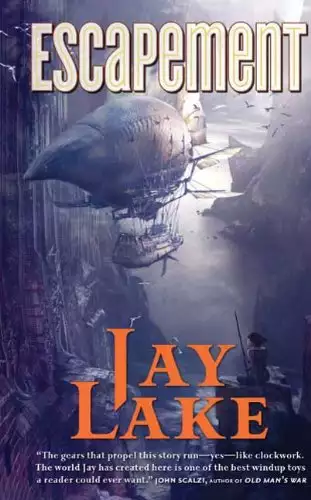

Synopsis

In his novel Mainspring, Lake created an enormous canvas for storytelling with his hundred mile high Equatorial Wall that holds up the great Gears of the Earth. Now in Escapement, he explores more of that territory.

Paolina Barthes is a young woman of remarkable intellectual ability – a genius on the level of Isaac Newton. But she has grown up in isolation, in a small village of shipwreck survivors, on the Wall in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. She knows little of the world, but she knows that England rules it, and must be the home of people who possess the learning that she so desperately wants. And so she sets off to make her way off the Wall, not knowing that she will bring her astounding, unschooled talent for sorcery to the attention of those deadly factions who would use or kill her for it.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: February 22, 2010

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Escapement

Jay Lake

P A O L I N A

The boats had been drawn up in the harbor at Praia Nova when the great waves came two years past. The men of the village generally thought this a blessing, for that circumstance had spared their lives. The women generally thought this a curse for much the same reason. A Muralha remained silent and unforgiving as ever, a massive rampart of stone, soil, and strangeness soaring 150 miles high to separate Northern Earth from Southern Earth. In the shadow of the Wall, there was less food than ever until boats could be rebuilt and nets rewoven, but no self- respecting man would go without dinner. So the women quietly starved themselves and their babies to keep the drunken beatings away.

No one starved Paolina Barthes, though. Demon- haunted or touched by God, in either case she had saved Praia Nova after the waves. Still, she was boy-thin and narrow- shouldered, not yet to her monthlies though she wore the black linen dress that all the grown women favored.

The fidalgos spent every Friday night in the great hall at the edge of Praia Nova. The building had been erected in an

absolute absence of architects or—at least prior to Paolina—engineers, but instead with the dogged determination of the

fidalgos that they knew best. Generations of pigheadedness had raised a monstrosity of coral cut from the reefs at the foot of a Muralha, granite chipped with slow, steady pain from the bones of the Wall itself, marble salvaged in furtive, fearful expeditions to the cities of the enkidus higher up. This resulted in something like a cross between a cathedral and a

toolshed. Still, it had survived the quakes that came with the waves, where many of the traditional adôbe houses had not.

It was a harlequin of a building as well. The mix of materials and styles across the years made the thing a patchwork, a

Josephan coat to shelter the guiding lights of Praia Nova in their wise deliberations.

This night, they were drunk and afraid.

Paolina knew this the way she knew most things. It was obvious from the scents in the air, the rhythm of the glasses pounding the table, the fact that another of Fra Bellico's children had been buried that day in the hard, thin soil on which Praia Nova huddled, 317 steps above the coral jetty and the unforgiving sea.

She walked toward the great hall on the path they called Rua do Rei— the King's Street. In truth only four men and one woman in Praia Nova had ever seen a street, and they had no king save the Lord God Almighty. Rua do Rei was just wide enough for two goats to pass, and had a rope strung to provide a grip during one of the great Wall storms off the Atlantic. One side opened into a ravine where the villagers threw what little garbage they were not able to intensively and obsessively reuse. The other passed close to a knee of a Muralha.

Juan and Portis Mendes had found a boy, but no one had brought him to her. Instead the fools had taken their prize to the fidalgos.

He was English, she'd heard, and had not come from the sea like every Praia Novado. Not from the sea at all, but down the eastern path through the countries and kingdoms of a Muralha toward mythic Africa.

Paolina hated, hated, hated being told things. All they had to do was let her see and she would find a way. When the

earthquakes dried the springs that watered Praia Nova, she'd built the pedal- powered pump to raise water from the Westerly Creek down near sea level. When Jorg Penoyer got his leg trapped up on the coal face, she'd figured out the pressure points in the rock and set rope-and-tackle rig to get him out without an amputation. She understood the world, and when the fidalgos managed to forget Paolina was a girl, they remembered that.

Even more she hated being told she was merely a girl. Not even a woman yet. God had not put her on this Northern Earth to squeeze out some lout's get like a she- goat every nine months after being topped. Women lived only to serve, while the pilas of the men made them Lords of Creation.

To hell with that, Paolina thought.

She stopped outside the great hall and stared up at the sky. The earth's track gleamed, tracing a brass- bright line across

the hemi sphere of the heavens, that barely bowed outward from a Muralha. The Wall itself remained mighty as ever, the

world's stone muscle, greater than any imagination could encompass.

Except hers.

Paolina smiled in the evening darkness. God could set His little traps. She would find her way out.

The rising blare of voices called her onward. She marched toward the doors of the great hall, closed now against evening's chill and the untoward attentions of people like her.

Inside, the men did what they usually did, which was pretend not to notice her. Dom Alvaro, Dom Pietro, Fra Bellico, Benni Penoyer, and Dom Mendes were pulled close around a plank table in the main hall, a bottle of bagaceira between them drained down to eye- watering vapors and bubbled glass.

The English boy—a young man, really—sat on a bench against the west wall. Half a leering face, broken off some great enkidu carving, was jammed into the stone above him. He was sallow and burned by the sun, with greasy, pale hair and a tired look in his eyes. Their gazes met a moment. There was no spark of recognition, no sense of a kindred spirit close to hand.

Just another man, then, in love with his own pila, to whom she was nothing more than furniture.

Still, Paolina wished she'd gotten to him first, before the stranger witnessed the drunken anger of the fidalgos. He would

think them nothing more than a village of fools. This boy, who must have seen London or Camelot once, now knew her people to be little more than asses braying in an unswept stable at the very edge of the world.

Paolina felt her anger rising again.

"We cannot afford him," shouted Dom Mendes. He was haggard, dusty to the elbows with the work of building new boats. Oh, they had not liked her opinion of that effort. "That old fool who lived among us before the waves came was bad enough, and we dwelt amid plenty then. There are too many mouths now."

"One less today," blubbered Fra Bellico, who had not missed a meal yet though he kept his Bible always close to hand.

"My boys hunt," Mendes hissed.

Penoyer snorted. "Yes, and bring back more mouths." No fidalgo he, his grandfather having come off an English boat by way of unsuccessful mutiny. Only quality took the titles of respect in Praia Nova.

Caught between anger and embarrassment, Paolina finally stepped up to their table. She shoved herself between Mendes and Pietro. "Do you suppose he might understand Portuguese?"

Bellico waved a pudgy hand. "He is English. The roast beefs never speak anyone else's tongue, only their own barbarous barf."

"Then I shall speak to him in English," she announced. "Perhaps he brings knowledge or tools with which to feed himself and others."

Penoyer, pale as a grub with hair the color of fireweed flowers, shot her a glare before answering in that language, "No good will come of it, girl."

The boy perked up a bit, then slumped down as the words sank in.

"It can't possibly get any worse," she snapped, also in English.

Let Penoyer explain it to the fidalgos.

Paolina stepped around to the boy. "Come with me," she told him, in his language.

He stood and followed her out, without a backward glance. Nothing lost there, she realized. Outside she turned to him. "I am sorry." She paused to frame her next words.

"Não faz mal," he replied, surprising her. It doesn't matter.

Despite herself, Paolina giggled. "You understood everything they said?"

"Most of it." English again.

"My mother has bread." It was the kindest thing she knew to do for the boy. She took his hand and tugged him along the path that was King Street, back to the houses of Praia Nova and their quiet, hungry women.

To save the expense of the candle, they ate on the back step of the hut. Paolina's mother washed and swept the stone daily. She'd been sitting quietly, staring out at the moonlit Atlantic when Paolina came for the bread, and did not stir.

So it had been in the years since Paolina's father's boat came back without him. Marc Penoyer had been captain. He and his two brothers had sworn a tale so alike it had to be concocted—even at six, Paolina had known no two people perfectly agreed on anything. People didn't see what was in front of them. They saw only what was dear to their hearts.

After that, her mother worked her days and dreamt away the nights. Sometimes she spoke, sometimes she didn't, but Paolina always had at least one dress. She'd never gone an entire day without eating something.

It was the bargain of childhood, she'd supposed. As her cleverness had begun to count for something extra, Paolina had made sure there was always a little flour from the sorry mill above town, always a little dried meat from the line- caught fish the idled boatmen brought in.

The boy asked no questions about her mother, merely gnawing the crust with a gusto that betrayed how long it had been since he'd eaten decently. She'd spared him only two chunks torn from the loaf, and a handful of dried sardinella, but Paolina knew that offering food made her civilized.

He'd seen London, a voice within her cried. London. Even Dr. Minor had not been there.

In that moment, she hated a Muralha, Praia Nova, and everything else about her life. She stared up at the brass in the sky, wondering how to break it and set free the earth, and herself.

"Thank you," the boy said.

"Hmm?" She swallowed the harder words which lay too close to her tongue.

"Thank you. They were going to throw me out of the village, weren't they?"

"Of course." Despite her anger, Paolina laughed. "You might say or do something dangerous. News of the world helps no one, serving only to make us doubt our traditions. Besides, we are starving."

"So am I."

She looked over at him. The boy wore a leather wrap, something that had been tailored in a sense, but as if sewn by cats who had only seen paintings of real clothing. He had a grubby, torn shirt beneath that, and a pair of canvas trousers that must have once been white. Bare feet, which made her wince.

"Sure you did not walk here along the Wall?" she asked him.

"I fell from a ship."

She resisted the urge to glance toward the ocean far below, but there must have been something in her face. He raised one hand in defense. "An airship. I fell from one of Her Imperial Majesty's airships."

Despite herself, Paolina was impressed. "You look well enough for a man who fell to earth."

"I had a parachute."

She didn't know the word, but she was not going to ask him to explain. It obviously referred to a device for retarding the

rate of fall. Cloth or ribbons could do that, though with his weight, it would need a wide spread to provide sufficient

surface area for braking. In the back of her mind, she began to work out the formula for the relationship between the size of the cloth and the weight of the load.

"I am Paolina Barthes," she said. "This paradise on Northern Earth is Praia Nova."

He stood and bowed awkwardly. "Clarence Davies, late the loblolly boy aboard Her Imperial Majesty's airship Bassett." After a moment he added, "Very late, for it has been two years since I fell overboard and began my walk along the Wall."

Now she was very impressed. "You survived two years on your own?"

He nodded, still looking both hungry and hunted. It could not have been easy—Praia Nova barely clung to life, and that was with several hundred people who at least theoretically could coordinate defenses and share what they had.

"You must know how to live out there, then," she said.

"Knew how to live aboard Bassett." His head drooped lower. "Stay out of Captain Smallwood's way, listen to what ever the doctor mumbles when he ain't drinking, watch out for the clever dicks like Malgus and that boy of his."

"You're not a— clever?" She was disappointed. He was English. They were the genius sorcerers who ran the world. Dr. Minor had taught her that, before he'd fled into the wilderness.

She'd learned so much from the old Englishman.

"Just a boy, me," Clarence said. "The officers and the chiefs, they know their business. Al- Wazir, he was a magician, could make a man do anything. Need to, I guess, to work the ropes."

The power of compulsion. That explained a great deal about the British Empire.

The boy went on. "Smallwood, too. The gas division. They walk in poison, you know."

"This Bassett was a magnificent ship?"

For the first time, Clarence Davies smiled. "The greatest. Soaring through the clouds on a summer day, looking down on them whales and sharks and fuzzy wuzzies . . ." His head dropped again. "I want to go back to England, though. But 'tis too far to walk."

"You flew through the air to come here, and now you cannot find your way home." Something in Paolina's heart melted, that she had not known was frozen. "They'll grumble for a month, the fidalgos, and never come to a decision. So I decide now. I invite you in my mother's name. We will find a boy's family for you to stay with, and I will make sure there is a bit more food."

"I . . . I . . . have nothing to give."

"Nothing is required. Help where you can, lend your muscles, speak to me in English." She smiled, trying to coax another

flash of bright teeth out of this Clarence. "There are few enough safe places on a Muralha. Stay here a while."

"Thank you." He came to some visible decision, a flash of relief and recognition in his face, then dug deep into an inner

pocket of his leather wrap. Clarence shoved a little bag at her. "Here. I don't need this. Ain't wound it in months. Smart,

clever girl like you maybe could use it."

The thing was heavy, a hunk of metal or glass. She pulled it out and corrected herself. A hunk of metal and glass. Round

face, with hours on it like a sundial and a heavy metal rim containing more weight. The face was topped by three metal

arrows. There were tinier faces within, with their own calibrations, and a little cutaway showing something behind the face.

She peered close and saw Heaven.

Gears.

It was God's gearing, the mechanisms of the earth and sky captured in the palm of her hand. Light flooded her head for a

moment, the dawn of a new awareness. Paolina's stomach knotted in something between fear and fascination. She'd had no idea that a person could fashion a model of the world to carry with him.

"It counts the hours," she whispered, her voice and hands trembling in awe.

"Yes." He touched a little cap extending from one end. "See? It's a stemwinder. A Dent marine chronometer that needs no key."

Her fingers lay on the knurls of the cap. At his nod, Paolina very gently twisted it.

The tiny model of the world within clicked, just as the heavens did at midnight.

This was Creation in the palm of her hand. The English were truly magicians.

Much to her surprise, Paolina began to cry.

Praia Nova had seven books. They were kept in the great hall, in an inner closet with the precious bottles used to contain

bagaceira when Fra Bellico found the necessaries to distill more, or the wildflower wine the women made when Fra Bellico lacked materials, time, or ambition.

There was half an English Bible, the Old Testament through the middle of Ezekiel. It was water damaged. The New Testament, with its stories of the Romans and their horofixion of Christ, existed in Praia Nova only as a scrawled leather scroll reconstructed from the memories of the various shipwrecked sailors who'd brought their indifferent faiths to the village over the generations. It did not matter what she thought of the prophets or the inept copy work of recent times—the Bible needed no more explanation than a look to the sky.

The other books were a different matter entirely. Her favorite was Fiéis e Verdadeiros Segredos, a Portuguese translation of a book that claimed to have originally been published in French, written by a Comte de Saint-Germain. It was a magnificent volume, bound in a slick, smooth leather that she was fairly certain was human skin. The title was stamped into the binding with traces of gold leaf and faded red pigment. There werelurid woodcuts within, lavishly illustrating scenes of debauchery from the ancient days. She'd spent time studying those, but had not yet divined the meaning of most. In any case, Paolina found it difficult to credit what Saint-Germain said of himself and the world. The man, whoever he had truly been, was an extraordinary storyteller at the least. She hoped to meet a Jew one day so that she could pursue some of the questions raised in Segredos.

There was also Archidoxes Magica, by Paracelsus. It was bound in boards, and quite damaged by damp and age. Furthermore, no one could aid her with the Latin. She had no second text to compare it with in order to puzzle out the language. As a result Paolina had struggled mightily with the book. In Segredos, Saint-Germain claimed to have known Paracelsus as an alchemist and physic, but that only told her one thing—fraud or genius, he had seen into the heart of the world.

That inspired her.

Three of the other books were pop u lar texts, two in English, one in Spanish: The Mystery of Edwin Drood by Charles Dickens, Mathias Sandorf by Jules Verne, and Cartas Marruecas by José Cadalso. There was also one volume in an alphabet that looked maddeningly familiar while making no sense at all. Paolina was surprised the last hadn't been burned for fire starter. She'd read through the English works many times, and puzzled through Cadalso twice.

She'd learned how strange the world was, beyond a Muralha and the goat-dung paths of Praia Nova. That, and how badly she wished she lived in a part of the Northern Earth where there were printing presses and libraries and bookshops.

Even Dr. Minor's visit to Praia Nova, while immensely improving her English and her knowledge of the world, had only deepened her dissatisfaction.

Now, though, now she had a trea sure beyond price. She had a pocket watch. A stemwinding marine chronometer, to be specific.

Neither the Bible nor Saint- Germain had anything to say directly about watches, though both certainly discussed

clockwork—albeit somewhat metaphorically in the Bible. Paracelsus was no help at all, and neither was Cadalso. Verne and Dickens, however, seemed fully in command of a world where pocket watches were ordinary.

In the days that followed, she reread both works carefully. The purpose of the watch would have been clear enough even if Davies had not explained it. Paolina was far more interested in the design and construction. She'd never so much as seen a clock. There were obvious inferences to be made about the mechanism from looking at God's design for the universe. He had written His plan in the sky, after all.

What Paolina wanted was a clear set of instructions.

The stemwinder was heavy in the pocket of her homespun smock. She knew it was there the way she knew her heartbeat was there. Wound, it ticked. Ticking, it reflected the world.

Time beats at the heart of everything, she thought.

It was one of those ideas that pricked a spark in her mind, a little flare that staked a claim of importance.

God had made the universe of clockwork. The world ticked and turned. Two years ago, it had stuttered. The great waves and quakes came from deep within, she knew. Midnight had slipped by a few seconds. No one else understood, and there was no point in explaining, but she'd known.

Then the world had been fixed. What ever time beat at the heart of the earth had been restored. Paolina wished she knew how. A question that ran through all the books (except the Bible, of course) was whether God acted directly in the world, or simply let His handiwork sort itself out.

Something had been sorted out.

And still time beat at the heart of everything. The stemwinder was a model of the universe, no larger than the palm of her

hand, no thicker than two of her fingers, and it ticked away the moments and hours just as all of Creation did.

Paolina put it close to her ear, listening with the words of Dickens and Verne and the Old Testament prophets close in her mind. Ezekiel 24:6 suggested itself to her in the gentle ticking deep within. Woe to the bloody city, to the brasswork in which there is verdigris, and whose verdigris has not gone out of it! Take out of it piece after piece, without making a

choice.

That was clear enough. God was telling her to take the watch apart.

Paolina's most difficult problem was finding a clean, clear workspace. Whatever gears and trains lay within the stemwinder were tiny reflections of the brass in the heavens. She'd need a room sealed from the winds, relatively free of dust and dirt, where the complex work could remain undisturbed in her absence.

The inner room of the great hall, among the books and bottles, would have been ideal. But even Paolina couldn't quite imagine how to get the fidalgos to come around to that. They would beat her for a stupid chit and set her to scraping moss off the water stairs if she had the temerity to even ask.

She wandered the village, looking at the houses and storerooms that comprised most of Praia Nova. The ones that were not inhabited were tumbledown. Paolina didn't want to contemplate the patience required to clean up an abandoned hut.

On the Oporto shelf, the second ledge above town, where more of the thin wheat fields ran, she realized she was looking at her answer—the mushroom sheds. They were sealed with lacquered canvas, and they were quiet. It would be a month or more before another set of trays was picked. All she needed was a bit of light.

Best of all, the women of the town ran the sheds. Senhora Armandires was the dame of the mushrooms. Paolina had built a much improved chimney in the woman's house last year, once Senhor Armandires had finally moved out for good and the senhora could make her own choices. The lady would make no objection.

Light was still an issue, but it would take little enough to see the watch. Candle stubs were her friends.

Paolina went off to find Clarence. He could help her drag a table out of one of the abandoned houses and up to the Oporto shelf. And a cloth to cover it.

She would find a way. This was the solving of problems. She was good at that.

During the course of the following days, Paolina opened the back of the stemwinder to observe the delicate movements of the mechanisms within. What she saw nearly turned her away from her project. She lacked the tools to grasp such miniscule things. She might be able to make those, in time, with scraps from the Alcides' smithy. She would need a lens, as well, scarcely possible here in Praia Nova. In any case, this was a task for the slow and patient. She stuck with picks and pries made out of hardwood splinters.

Clarence was something of a help, ghosting about and answering her occasional question. He spent time foraging, too, farther from Praia Nova than most of the locals would go. Of course, he'd walked the Wall for two years—the boy had survived far stranger things than the glittering, scaled cats that occasionally prowled the ledges here, or the bright, frigid rocks that sometimes bounded down from higher up.

He came running in the eve ning of her fourth day in the mushroom shed. Panting, sweating, as the whites of his eyes gleamed in the light of her little candle stub. "The fidalgos are looking for you!" he shouted in Portuguese.

"Someone is always looking for me." A tiny stab of fear stole into her heart.

Davies switched to English. "You have been summoned. Senhora Armandires argues with Fra Bellico down in the village."

Paolina sighed and put down the teakwood picks. She carefully covered the stemwinder with a square of pale silk, part of the bounty harvested from the body of a Chinaman brought up in the nets the year before the big waves. "What does the good father want of me?" She dusted off her hands.

Clarence looked down at his feet a moment. "The fidalgos are angry."

The answer was obvious now, but her rising irritation made her unkind. "About what are they angry, Englishman?"

Walking behind her through the canvas flap that was the door, he mumbled some answer she couldn't hear.

"Pardon?" Nasty now.

"That you were given the watch."

"That I was given the watch." Her singsong tones mocked him. What had she ever thought worthy of this idiot boy? "The heavens opened up and spat a watch into my hands, which by the grace of God should have been given to the men of Praia Nova, is that it?"

"I'm sorry," he muttered, but she already raced down the paths toward the shouting.

The fidalgos were drunk and angry. The first thing Paolina realized was that they were into the wildflower wine. The

bagaceira was gone, and Fra Bellico had not found any more of the wild grapes and plums from which to press his pomace and make more. No wonder they were upset, forced to drink a woman's swill.

The five were drawn up to their table again, facing her: Alvaro, Pietro, Bellico, Penoyer, and Mendes, who chewed his

moustache and looked thoughtful. The rest merely seemed possessed by the same tired anger that had gripped the men in the village since the fishing fleet had been lost.

They badly missed the seafood trade with the enkidus and the downtrail tribes.

"You!" roared Bellico. "Thieving girl! We should sell you up a Muralha."

"I have stolen nothing," said Paolina. "I give you everything and more. What is it you want now?"

"What is our due," Mendes said quietly, casting a sidelong glare at the others. "What the boy mistakenly set in your hand."

"What he gave me?" She let her voice seethe with contempt, though in truth these men scared her. Not for who they were, but for what they could do. The fidalgos in council, which they were now, were judges and swords of the law in Praia Nova. Never mind that no one owned such a blade.

This was as large a matter as they'd ever broached her over.

"The watch," said Penoyer. He was flush, even in the candlelight, with a graceless air of shame.

"You want me to give you my watch?" As with Clarence, she would make them say it.

"Yes!" It was Bellico again. "The village could do much with that wealth of metal. Trade it, keep it for a trea sure. Not let

it be greased by the clumsy hands of a youthful Carapau de Corrida with more ambition than sense!"

"Fra," said Paolina slowly and deliberately. "If you call me that name again, I shall make sure your still produces nothing

but vinegar, and your pilinha will burn every morning for the rest of your days."

"She's a witch," muttered Alvaro. "Always was, little chit."

"Enough," said Mendes. He was not the bull among them—that was Fra Bellico—but he was the only fidalgo with enough sense that Paolina could consider having respect for him. "It does not matter. What matters is you took an object of great value, easily considered salvage and thus the property of all, and have hidden it away. That should have been the decision of the village."

"You mean your decision." Paolina just couldn't stop herself from speaking. The men didn't merely believe they were

entitled—they were entitled. This transcended reason.

"Our decision is the decision of village." Mendes leaned forward, the room around him now quiet, the guttering candle filling his eyes with shadowed darkness. "Your decision is not."

And there it was. The truth of the matter. She might as well argue with a Muralha as argue with generations of tradition.

"No," Paolina told him. "You cannot have it until I am done."

"You will not obey the decision of the fidalgos in council?" Mendes asked. Slowly, carefully.

She was on an edge here. But she simply couldn't give in. If she did it now, she was lost. "No." It was amazing how easy that word was to repeat.

Mendes glanced at Bellico in particular. The father took a deep, shuddering breath, then nodded. "Very well. At fifteen, you are old enough to heed the will of the village or pay the consequences. I only regret we did not take you in hand earlier."

They were getting up from the table, chairs scraping, feet shuffling as the large drunken men encircled her.

Paolina felt a stab of fear. She shrieked when they grabbed her, already clamping her knees together, but the fidalgos

dragged her to the back room, shoved her in with the books and bottles, and shut the one door in all of Praia Nova that

actually had a key.

It took her a while to cry, and longer to begin screaming, but the door remained thick, wooden and locked no matter how she pounded and pleaded. In time, they doused their candle and left. She didn't know whether the wine had run out or they had tired of the noise of her fear.

Excerpted from ESCAPEMENT by Jay Lake.

Copyright © 2008 by Josepth E. Lake Jr.

Published in June 2008 by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to

reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...