LONDON 1824: KENSINGTON HOUSE

Never knew a moment made better standing still. Never knew an hour made perfect by silence.

It’s been a long time since I’d had peace—moments of dance, hours in hymns. It disappeared when the Demerara Council forced its tax.

Fidgeting, I sit in the front parlor of Kensington House switching my gaze from the sheers draping the window to the finishing school’s headmistress. Miss Smith, she’s across from me in a Chippendale chair sipping her chamomile tea. Her fingers tremble on the china handle.

“Mrs. Thomas,” she says with eyes wide, bulging like an iguana’s. “Your visit is unexpected, but I’m pleased you’ve taken my offer to stay at Kensington to review our school. You’ll see it’s a worthy investment.”

“I was always fond of the name Kensington.”

My voice trails off as I think of walks, of choices, then my aptly named plantation. Kensington is a set of squiggled letters chiseled in a cornerstone back home.

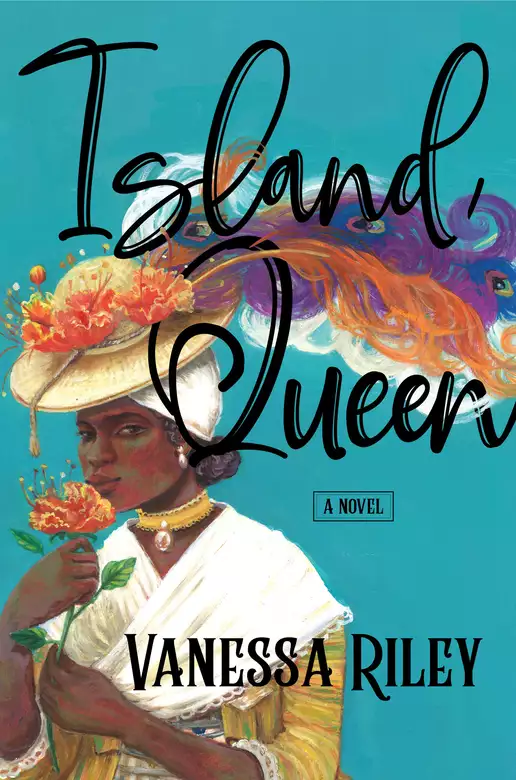

The headmistress chatters on, and I nod. The white egret feather on my bonnet jiggles and covers my brow. I bat it away like the memories I want gone, but you never get to choose what comes to mind.

“Thank you for your hospitality, Miss Smith.” She dips her pointy chin.

The loud clink of her teapot on my cup’s rim gives us both away— her nerves, mine.

“Sorry, ma’am. I don’t know what’s come over me.”

She sets the pot on the mahogany table that lies between us.

“This silver service you’ve given to the school is always treated with respect.”

Respect.

If I rest my lids, that word said in different voices from the past— friends and enemies—haunts me.

So, I don’t move, not even a blink.

I forgive the headmistress’s babbles. She’s a good fund raiser, and I have a soft spot for females that know figures. “My late arrival must’ve upset you. I apologize.”

Didn’t think it possible for her eyes to spread wider. She mustn’t be used to someone taking responsibility for causing trouble. I own mine, every bit.

“It’s nothing,” she says with a limp smile. “A benefactor is always welcome.”

The demure lady with her sleek jet coif bobbling waves a tray of shortbread treats. “Biscuit?”

“No. The tea’s enough.”

“Oh, yes.” Her head lowers. The poor thing looks deflated again, like a sloop’s drooping sail the wind has abandoned.

Looking away to the empty street—no carriage, no visitor, I let a frown overtake my lips. A glimpse at the fretting Miss Smith forces me to wipe it away.

Arrayed in beige silk with shots of Mechlin lace along her sleeves, she’s shifting, rocking back and forth. I don’t know how to help her, not when I have to help me.

I’ve lived a long time.

I’d hate to reinvent myself now.

The Demerara Council can’t steal my life. Those men can have none of what I built.

The curtains flutter.

The gauzy sheer, like fine Laghetto bark spun into a veil, frames the empty street. My restless, anxious heart begins to spin.

The headmistress’s nervous tapping reminds me I alone am not at risk. All colored women are.

“More tea, ma’am? I was wondering if you wanted more tea, Mrs. . . . Mrs. Thomas. That’s all.”

Mrsss. Thomassss. She says my name like I like it, with all the important s’s in place.

“Out with it. Miss Smith, tell me what’s the matter.”

My voice sounds stern, and the poor woman sports a full-face blush, from chin to brow. She might fade into the parlor’s pink-papered walls. She’d definitely pass undetected in the big houses of Demerara or Dominica or Montserrat. Grenada, too. The fair-skinned coloreds often did.

“Your granddaughter loves Kensington House, ma’am.”

“I won’t be moving Emma Garraway to the prestigious Maryle- bone school like I did her cousin, Henrietta. I prefer her to study here.” Where she’ll be watched and kept far from scandal or worse, a marriage that was beneath her.

I won’t voice the last part.

The disappointment in my children’s and grands’ choices keeps company with my own regrets.

Miss Smith’s lips ease into a smile. “We love Emma. She’s most promising, but Henrietta Simon, now Mrs. Sala, was a brilliant student, too.”

“Yes . . . she married her Marylebone music teacher.” My Henrietta. My Henny. I had such hopes for my granddaughter.

“Did you come for her wedding? I heard she was a vision in silver.”

“No. It was the wet stormy season in Demerara. I was unable to cross the sea then.” I sent Henny my best wishes and a dowry. The latter might be more important to the couple.

“Your knees, ma’am. They’re knocking. Are you cold? Do I need to stoke the coals or send for a blanket? Visiting from the tropics, it can take some time to adjust to London’s chilly weather.”

“No. No fussing right now.”

The headmistress shifts in her chair as if I’d barked.

I smooth my pale plantain-yellow-colored skirt, heavy in lace, heavy in trim. These straight-shifted gowns do little to hide my tension. How will I prove my points to the secretary in his grand office if my knees betray me in a finishing school?

When trying my hardest to hide, something whispers my truth. “Ma’am?”

Miss Smith is waving, drawing me back from the shadows. “We’ve done a great deal to the school. You’ll be happy with your . . . all the investments we’ve made.”

Her tone is fast as if she’s racing in a dray, wheels spinning, horses hoofing. The woman should be confident in her work.

I sigh, my breath mixing with the steam of the lemony chamomile. She should know I see her. What she’s created matters. I plink the cup like a clarion’s bell. “Miss Smith, I’m pleased. The school is good.”

Even as my eyes drift to the window, to the empty street, I catch the headmistress signaling again.

“Oh, I had Emma take up embroidery. That’s new. We’ve added a live-in seamstress since your last visit. This is your third trip to England?”

“I’ve been to Europe many times since eighty-nine.”

“Eighty-nine? That early . . . I-I-I hope you’ll enjoy this one.” Her words have peaks and valleys and a funny sense of surprise between her stutters.

“What’s wrong, Miss Smith?”

“Nothing much, ma’am, but the new pianoforte teacher we hired, Miss Lucy Van Den Velden, she said you’d been here then. I thought she was confused.”

Miss Van Den Velden is a meddlesome soul from Demerara. She tips her thin nose into others’ business. Her father serves on the council under awful Lieutenant Governor Murray. Those men are happy to make laws threatening colored women. One would think the mulatto miss would voice concern, maybe change her father’s mind. Then this burden wouldn’t be mine.

“Miss Van Den Velden’s quite anxious to see you. When I let her know you were coming, she told me she couldn’t wait. She has news clippings to share.”

Not news clippings, but a clipping. A single image.

One solitary sketch printed in Rambler’s Magazine to shame a young sailor and me. The memories. My pulse stutters. My cheeks burn. The truth lights matches to my skin.

If the scandal reaches the secretary of state for war and the colonies, the man who rules England’s territories around the world, he won’t take my meeting. He’ll dismiss me, a woman who’s worn shackles and the labels of whore, concubine, and cheat.

But no one knows my story, the shame and the glory.

Smoothing the crinkles from my shawl, I wrap it tighter about my limbs and force myself to remember I’m not that girl anymore, the one who ran from trouble or barreled toward it.

The survivor in me leans forward. “You make sure Miss Van Den Velden spends time with me. I’ll end her confusion.”

“Yes, ma’am.” Miss Smith sips her tea and ignores the scythes scraping in my words. “The gardens. I haven’t told you of them. Would you like to see the flowerbeds, now? What about a tart? They are freshly made.” Miss Smith sweeps the tray closer as if my sight has dimmed.

It hasn’t. It’s still selective, seeing what I want. “No, Miss Sm—” “Mrs. Thomas, I can’t take any more.” The headmistress’s cheeks are fiery red, redder than the flesh of a cashew cherry. She flings herself out of the chair. “You’re displeased. I’m sorry, but please reconsider. Don’t end your funding of Kensington House.” “What?”

“Our girls need the education. We’re the best place. We readily accept our young women from the West Indies. We make sure colored girls have the best beginnings.”

On her knees, she clasped her hands high. “I try hard to prepare a good environment.”

Setting down my cup, I grasp the woman’s small palms, her light ones in my dark, dark fingers. Sharing my power, I help her up. We stand together. “Be at ease. I’m not unhappy with you or the school.”

Can she see beyond my wrinkles to the pride bubbling? I’ve helped this woman build her dream, something good, something lasting.

Relief sweeps across her face. A small smile buds, then blooms with teeth. “Thank you, ma’am. Since your arrival, I’ve been fearful.”

Then her lips shrivel, like her leprechaun’s pot of coins has become lead. “Then why do you look as if you have bad news.”

“I must meet with Lord Bathurst, the secretary of state for war and the colonies. He’s the overseer of Demerara and all the Leeward Islands—my Dominica, Montserrat, and Grenada.”

She glares at me. “But he’s a high official. Ma’am, why Bathurst?

A meeting, I mean?”

“The secretary can fix what Demerara’s governing council has done. They’ve put a tax on colored women, just us. We’re forced to pay the damages wrought by slave rebellions.”

“Not all citizens? That’s not fair.”

“This is how legal terror begins. What will stop these men from making laws that cancel our leases, bills of sales, even manumission records? They’ll enslave us again.”

Miss Smith’s face turns gray. “Then Godspeed to you, ma’am.

You have to convince him.” “I know.”

One chance, one meeting, that’s all I’ll get to persuade Bathurst.

Wham.

The door of the parlor flings wide. It’s my Mary, one of the youngest of my line.

“Look, look, GaMa.”

Mary Fullarton struts across the room with a book on her braided crown. My grandbaby twirls. Her white silk gown floats about her as she moves from the hearth to the window. “Cousin Emma showed me what to do. She let me borrow ya book.”

My book?

Mary probably saw hundreds shelved in my parlor. The child must think I own them all, everywhere. I smile, not correcting a thing.

Little girls need to dream and think they can own everything. “Mary, sit with me.” Miss Smith gathers the small child onto her lap. “I’ll help you read. When you’re older, you, too, can be a student here if your grandmother likes.”

It’s a fetching picture to see the two flipping pages, fingering words.

The injustice of what governing men can do to our women boils my veins. My hot blood is Demeraran sugar thickening to caramel, turning char black. I want every threat gone, burned to nothing.

I seize a breath, steadying myself in the soft cushions of the chair. My friend, my damfo, is working to secure a meeting. It’s been five days since I sent a note. Maybe promises said along the shore have grown brittle and broken with age. Time does that, breaks things.

I sit with eyes closed, listening to Miss Smith and Mary sound out words.

My gut says I’ll win for her, for them. But my heart knows to get Lord Bathurst to rescind the tax, I’ll have to smile and hold my tongue.

Being silent on matters of justice—that’s something I’ve never done.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved