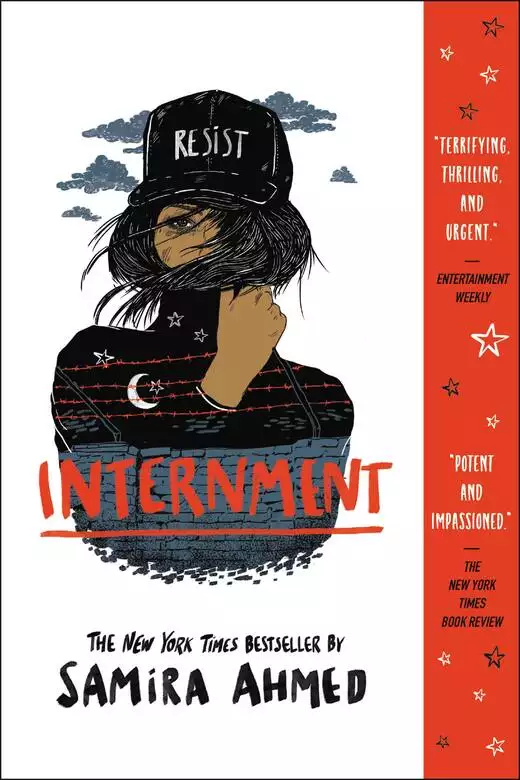

Internment

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Rebellions are built on hope.

Set in a horrifying near-future United States, seventeen-year-old Layla Amin and her parents are forced into an internment camp for Muslim American citizens.

With the help of newly made friends also trapped within the internment camp, her boyfriend on the outside, and an unexpected alliance, Layla begins a journey to fight for freedom, leading a revolution against the internment camp's Director and his guards.

Heart-racing and emotional, Internment challenges readers to fight complicit silence that exists in our society today.

Release date: March 19, 2019

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Internment

Samira Ahmed

But there’s nothing. Only the familiar chirp of the crickets, and the occasional fading rumble of a car in the distance, and a rustle so faint I can’t tell if it’s the wind or the anxious huff of my breath. But everywhere it’s the same as it’s always been: the perfectly manicured lawn of Center Square, the gazebo’s twinkling fairy lights, the yellow beams from the porch lamps at every door.

In the distance, I see a funnel of smoke rising into the air.

Most of the town is at the book burning, so I should be safe.

Or, at least, safer.

I don’t measure time by the old calendar anymore; I don’t look at the date. There is only Then and Now. There is only what we once were and what we have become.

Two and half years since the election.

Two years since the Nazis marched on DC.

Eighteen months since the Muslim ban.

One year since our answers on the census landed us on the registry.

Nine months since the first book burning.

Six months since the Exclusion Laws were enacted.

Five months since the attorney general argued that Korematsu v. United States established precedent for relocation of citizens during times of war.

Three months since they started firing Muslims from public-sector jobs.

Two months since a virulent Islamophobe was sworn in as secretary of war—a cabinet position that hasn’t existed since World War II.

One month since the president of the United States gave a televised speech to Congress declaring that “Muslims are a threat to America.”

I thought our little liberal college town would fight it longer, hold out. Some did. But you’d be surprised how quickly armed military personnel and pepper spray shut down the well-meaning protests of liberals in small, leafy towns. They’re still happening, the protests-turned-riots, even though the mainstream media won’t cover them. The Resistance is alive, some say, but not in my town, and not on the nightly news.

Curfew starts in thirty minutes, and this is a stupid risk. My parents will absolutely freak out if they find that I’m not in my room reading. But I need to see David.

I force myself to walk calmly, head forward, like I have nothing to hide, even though every muscle in my body shrieks at me to run, to turn back. Technically, I’m not doing anything wrong, not yet, but if the police stop me—well, let’s just say they have an uncanny ability to make technicalities disappear.

Breathe.

Slow down.

If I rush from shadow to shadow, I will attract attention, especially from the new motion-sensitive security cameras mounted to the streetlamps. Curfew hasn’t started yet, and I’m allowed outside right now, but it’s already dark. Even here, where almost everyone knows me and my parents—maybe because of that fact—my heart races each time I step out of the house. I cross at the light, waiting for the walk signal, even though there are no cars.

I spy a flyer for the burning taped around the lamppost at the corner: JOIN YOUR NEIGHBORS. The words are superimposed on a cascade of banned books, dangerous books. A hard knot forms in my stomach, but I keep walking, eyes still on the poster, and bump headlong into a woman rushing in the opposite direction. She stumbles and drops her bag. Books and flyers fall to the ground.

I bend down to help her pick up her things. “Sorry, I wasn’t looking where I was going.” I try to be polite, deferential. Stay calm, I say to myself. It’s not past curfew yet. Don’t act guilty. You’re not guilty of anything. But these days, actual guilt is an afterthought.

The woman keeps her head turned away from me, refusing to meet my gaze, shoveling the books and papers back into her bag. I reach for two books and glance at the titles before she grabs them from my fingers. Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz. Nameless Saints by Ali Amin—my father.

For a split second, she looks me in the eye. I suck in my breath. “Mrs. Brown, I—I’m sorry—” My voice fades away.

Mrs. Brown owns the Sweet Spot on Jefferson Street. She made my favorite birthday cake ever, a green-frosted Tinkerbell confection for my fifth birthday.

She narrows her eyes at me, opens her mouth to speak, and then clamps it shut. She looks down and pushes past me. She won’t even say my name. Her flyer for the book burning somersaults away in the breeze. I shrink into myself. I’m afraid all the time now. Afraid of being reported by strangers or people I know, of being stopped by police and asked questions to which there are no answers.

I pick up the pace to cross the town square, staring straight ahead, wiping the fear off my face, fighting the tears that edge into the corners of my eyes. I can’t suffer looking at the university’s gleaming glass administration building—all clean lines and razor-sharp edges that cut to the bone. David’s mother teaches chemistry at the university. My dad teaches poetry and writing. Did teach, I should say. Until he was fired—mysteriously deemed unqualified for the tenured professorship he’d had for over a decade. That’s another “Before”: two months since my dad lost his job.

My mind lingers on Mrs. Brown. She knows me. She’s seen me. And in minutes I’ll be in violation of curfew. I’m obviously not going to the burning; I should be home. The hard knot in my stomach grows.

I remember a lesson from my psychology class about an experiment in which volunteers were asked to torture people who were in another room by pressing a button that supposedly delivered an electric shock. It didn’t really, but the volunteers didn’t know that; all they heard were screams. Some resisted at first. But most of them pressed the button eventually, even when the screams got louder.

David is waiting for me at the pool house in his neighbors’ yard. They’re on vacation in Hawaii. Vacation. I can’t even imagine what it would be like to be able to go on vacation right now and not worry about being stopped by the TSA for a secondary search that could lead to being handcuffed to a wall for hours. Or worse.

David is taking a risk, too, though we both know it’s not the same for him. He may be brown, almost browner than me, and Jewish, but right now, it’s my religion in the crosshairs. We were suspended for two days from school for kissing in the hall, in the open, where everyone could see. We weren’t breaking any laws. Not technically. But I guess the principal didn’t want to look like he was encouraging relationships between us and them. Apparently, PDA is against school rules, but I’ve never heard of anyone pulling suspension for it. Even worse, although David got booted, too, only my parents and I were called in for a lecture about how I should know my place at school, keep my head down, and be grateful for the privilege of attending classes there. I was gobsmacked. My dad nodded, took it in stride. My mom did, too, even though she wore a scowl the entire time we were in the office. Then, when I started to open my mouth to say something, my mom shook her head at me. Like I’m supposed to be thankful to go to the public school where I’ve always gone, in the town where I’ve always lived.

Why were they so quiet? Especially Mom? She’s almost never quiet.

I left school that afternoon, and my parents were too scared to let me go back.

The pool house door is ajar. I catch my breath for a second before stepping inside.

“Layla,” David whispers, touching my cheek with his fingers. David has his dad’s gray-blue eyes and his mom’s deep-golden-brown skin. And a heart bursting with kindness.

A single candle glows at the center of the coffee table. He’s drawn the curtains in the small studio space—a white sofa piled high with navy-blue pillows, some with appliquéd anchors on them; a couple of overstuffed arm chairs; lots of faded pink and ivory seashells in mason jars; and, on the wall, a framed poster declaring LIFE’S A BEACH against white sand and cerulean sky and sea.

We’re alone. I imagine that this is what it must’ve been like decades ago, before the cold lights of computer screens and tablets and phones permanently eliminated the peace of darkness from our lives. Without saying a word, I walk into David’s arms and kiss him. I pretend the world beyond the curtains doesn’t exist. Being in his arms is the only thing that feels real right now. It’s the only place where I can pretend, for a moment, that we’re still living in the Before, in the way things used to be. I pretend that David and I are making plans for summer, that we’ll play tennis some mornings, that we’ll go to movies. I pretend that I’ll be graduating in a few months and going to college, like my friends. I pretend that David and I will exchange school hoodies. I pretend that high school relationships last into college. Most of all, I pretend that this magic hour is the beginning of something, not the end.

We sink to the sofa. While we kiss, he runs his fingertips along my collarbone. A whisper-light touch that makes me shiver. I nuzzle my face into his neck. David always smells like a nose-tickling combination of the floral laundry detergent his mom buys and the minty soap he uses. I know his mom still does his laundry. She babies him. I tease him about it—about how in college all his white clothes will come out pink because he won’t remember to separate his wash. I sigh. I brush my cheek against his, feeling the odd patch or two of uneven boy-stubble. We hold each other. And hold each other.

It would be a perfect moment to freeze in time and make into a little diorama that I could inhabit for an eternity. But I can’t.

I rest my chin on David’s chest. “I wish I could stay here forever. Is there a magic portal that will transport us to some other dimension? A Time Lord, maybe?”

“Should’ve stolen the TARDIS when I had the chance.”

My dad badgered us into watching Doctor Who, starting with the old-school episodes, and we got hooked. Since then we’ve had on-and-off binge-watching sprees. Despite the sometimes ridiculous production values, the monsters can be terrifying. It’s one of our things.

I give David a small smile. He could always make me laugh, but humor stabs now. I miss dumb banter. I miss laughter that doesn’t make me feel guilty. I miss laughter that is simple joy.

Everything about being with David feels natural, like the crooked, happy smile he’s wearing right now. Like the comfortable moments we can pass in silence. Like our ability to just be with each other. We’ve known each other since grade school, but it was last year at the homecoming bonfire that we had our first kiss. David sat next to me and took my hand, intertwining his fingers with mine. It felt like waking up to a perfect sunrise. Around us, everyone was drinking and rowdily mock singing the school fight song and making out, but all we did was sit there, holding hands. And as the crowd started to thin in the shadows of the dying embers, I turned to look at David. And when I wiped a bit of white ash from his forehead, he brought my hand to his lips and kissed my fingertips. I reached up and kissed him, my heart pulsing in every cell of my body.

Looking back now, I think I gravitated toward David because, like me, he was different. His dad’s family is Ashkenazi, and on his mom’s side are Jewish refugees from Yemen. Maybe politics and borders were supposed to keep us apart, but David and I built a safe space, a nest where our differences brought us together.

I look into David’s eyes and squeeze his hand. We both know that I have to go, that this evening can’t last. Without a word, we stand up from the couch. I zip my hoodie. David wraps his arms around my waist and peppers my face with gentle kisses. My heart thrums in my ears. I could live in this moment forever, let time fade away until we wake on the other side of this madness.

“I wish we had more time,” David says.

I know he means he wants us to have more time together tonight. I can’t help but take his words as meaning something more. Time has a weight to it now. A mood. And it’s usually an ominous one. “‘The world is too much with us; late and soon,’” I say, and kiss David on the cheek.

He knits his eyebrows together, a little confused.

“It’s from a million-year-old poem by Wordsworth that my dad made me read, about how consumerism is killing us and we don’t have time for anything really important, but I sometimes read it as, the world is out of whack—”

Our phones beep at the same time. I check my screen, and a Wireless Emergency Alert flashes:

One People, One Nation. Tune in at 9:00 p.m. for the president’s National Security Address, to be broadcast on all channels.

It’s a reminder about the weekly speech tonight. Two weeks ago, the president’s speeches became required viewing. All other programming on television and radio stops. The internet doesn’t work. The text of the speech scrolls across phones. Technically, I suppose, you could turn your television off, but my parents keep it on, with the volume low. My parents are too afraid now of making mistakes.

“Can you believe this crap? The alerts are supposed to be for, like, missing kids, not speeches from bigots.” David shakes his head and squeezes my hand tighter.

“I really have to get back,” I say. “The bonfire will be over soon. People will be walking home.” I think of bumping into Mrs. Brown, her squinting eyes. “My mom will die if they catch me.”

David takes a step back; his jaw clenches before he speaks. “Bonfire? Let’s not use euphemisms. They’re burning books in the school parking lot. They’re fucking burning books. My mom’s a damn professor, and she’s going along with this. And my dad, both of them, really—”

“I know,” I whisper. “It’s my dad’s books. His poems.” My voice cracks, and tears fall down my cheeks. I brush them away with the back of my hand. “They’re burning his poems. He pretends it’s not happening. But those words are him. He’s trying to hide it, but I know it’s killing him. Both of my parents. All of us. Is this how the end begins?”

“It’s not the end of anything,” he says. “Especially not of you and me.”

“Sure. Right. As if your parents haven’t forbidden you to see me.”

“It’s my dad. He’s being a total asshole. And my mom, she’s going along with him. I think she’s too terrified to speak up.”

Part of me thinks I should say something, tell David that his parents aren’t so terrible. But I can’t. I won’t. They stay quiet, using their silence and privilege as a shield to protect themselves.

“We’ll fight this. People will fight this—are fighting,” David says, trying to reassure me. I know he thinks he needs to be strong, to make it seem like he believes his own words, but I don’t think he buys it; I can tell from the way his smile curves down at the edges. I can tell because his left hand is balled into a fist even as his right arm envelops me. I nod and give him a grin that doesn’t reach my eyes. We accept the lies we tell each other and ourselves, I suppose. It’s one of the ways we are surviving the day-to-day without going mad.

At least this isn’t pretend. I nestle into David’s chest, and he kisses the top of my head.

When we first got together, I thought it might be weird to date a friend, someone who’d known me so long. The first time we walked through the school doors and down the hall holding hands, my palm was so sweaty it kept slipping away from David’s. He held on tighter, knitting his fingers through mine. Kissing my forehead when he dropped me off at my locker. Easy. Natural. Kind. Like we were something he always knew we would be.

There’s rustling outside the window. Our heads snap up. A bright LED beam dips back and forth across the lawn. David raises a finger to his lips. I don’t move. I can’t move. My heart pounds in my chest.

After an eternity, the light goes out.

“You’ve got to get home,” David whispers to me. “I’ll walk you.”

“No. It’s too dangerous.”

“It’s more dangerous for you.”

I look at my watch. Seventeen minutes past curfew. What was I thinking?

We clasp hands and tiptoe to the door, slowly opening it. David sticks his head out first, then whispers back, “It’s okay. No one’s out here.”

I take a deep breath and step out. That was close. Too close. This was foolish. Perfect, but stupid.

We race across the lawn, an acrid burning smell heavy in the night air. Over the tops of the roofs a column of smoke still rises, higher now than before. Blackish-gray wisps of words and ideas and spirits, a burnt qurbani ascending to heaven for acceptance. I can’t tell if the tears in my eyes are on account of smoke or grief.

“Stop!” a voice like sandpaper yells from behind us, flooding the darkness with a cruel light. We keep running, faster now.

“Go!” David shouts to me as he slows to swivel around, pulling his hand away from mine.

I stop, almost stumbling over myself. “I can’t leave you.”

David pushes me into the darkness. “It’s not me they want. Run!”

Tears blind me while I race home. As I approach my yard, it dawns on me that I might be able to outrun the person who was chasing us, but no matter how fast I sprint, I can’t escape this new reality of curfews and clandestine meetings and cinders rising in the air.

I push through the front door and slip inside, quickly shutting it behind me. I’m panting, my heart racing, wiping the tears from my face with my sleeve, terrified out of my mind that David might’ve been caught by whoever was waving around that flashlight in the darkness. I’m smacked with the smell of frying onions and adrak lehsan. The smell of home juxtaposed with the sweaty, breathless odor of desperation and the taste of rust in my mouth.

My parents rush out of the kitchen. My mom’s mouth falls open. The blood drains from her face, and she rubs her eyes with her hands, clearly wanting to erase this moment. She steadies herself against the whorled bird’s-eye maple console table in our foyer, my parents’ first flea market find as a couple, years before they had me.

My dad is every inch the professor. Thin but not muscular, with wavy hair that always looks a bit messy, grays sprouting up here and there among the dark chestnut brown, and black-plastic-framed glasses that he prefers to contacts. He takes his glasses off and rubs the little reddish indentations along the sides of his nose. He always does this when he’s contemplating something deep or worrying.

“Layla,” he says, “explain yourself. Were you outside? Now? At night?” His voice is firm, but he doesn’t yell. My dad is not a yeller. He barely raises his voice at me, even when I deserve it. This is clearly one of those moments.

My mom’s voice, however, is less restrained than my dad’s, as always. She doesn’t wait for me to answer him. “You were supposed to be in your room. It’s after curfew. What were you thinking? I can’t believe you would do something this foolish. Do you know what could’ve happened?”

She shakes her head, clenching her jaw, fury and fear flashing in her eyes. They’re lighter brown than mine, with specks of hazel and green, what she claims is the assertion of her distant Pashtun blood.

My mom’s voice trails off because we all know what could’ve happened. There are whispers of Muslims who have disappeared. Muslims like us, who answered the census truthfully when asked about our religion. Muslims who refused to hide.

I stare at my worn gray Converse All-Stars and try to scrape off the dirt from one scuffed toe with the other.

“Layla. Answer your mother,” my dad says. Mother. He might not yell, but he uses formal titles when he’s really mad.

I answer, my voice barely a whisper, “I was with David.”

“David? You broke curfew to see David? Are you crazy?” My mom turns her back to me, pauses, then walks into the large main room of our house, a living room that flows into a sunroom in the back. She falls into a cream love seat tufted with multicolored cloth buttons and stares into the fireplace. She’s like me; I know that her synapses must be on rapid fire, but my mom’s practiced meditation for years. She says it’s the only way she’s found to calm her mind. Wordlessly, she reaches up to the nape of her neck and undoes the loose bun she wears when cooking. Her dark hair, accented with the occasional gray strand, falls around her face, shielding it from me. I see her fingering her rosewood tasbih bracelet. I don’t need to see her mouth to know she’s uttering a prayer.

“Beta,” my dad says, using the Urdu word for “child.” If “mother” and “father” are signals of his anger, “beta” is the clearest sign of his love. “I know this is hard for you, but understand that David won’t face the consequences you will. You can’t take these risks. Your mom and I, we’re afraid for you.”

“I know. I’m afraid, too. But David is the only bit of normal I have left. Please don’t make me give that up.”

My dad winces a little, like my words have struck him. He glances down at the tan leather Indian khussa slippers he wears inside the house, like he’s measuring them up, as if he’s wearing them for the first, and not the millionth, time. Even though he’s not going to work anymore, he’s still in his teaching uniform: navy V-neck sweater and jeans.

“Beta, you can’t leave again so close to curfew. It’s too dangerous. We know it feels like prison. But it’s for your safety. It’s not up for discussion.” Dad prides himself on being even-keeled, even when he’s angry. Now, as he stares at me, it’s like looking into my own wide, dark brown eyes.

I nod like I agree, which I don’t, but I need this conversation to end because I’m desperate to text David to find out if he’s okay. I’m not sure Dad believes me, but he accepts my nod as acquiescence. More pretending. More lies we tell ourselves because reality is too much to hold all at once. He gives me a mirthless smile and walks toward my mom.

I make my way to the foot of the stairs and take a seat. I dig my phone out of my pocket. I need to tell David that I’m home, I’m safe. He’s probably out-of-his-mind worried, too, like I am about him.

One thing that isn’t pretend? Surveillance. I may do stupid things, I may risk getting busted after curfew to see my boyfriend, but I’m not dumb enough to send a regular text. We use the Signal app so our texts are encrypted.

ME: I’m home. Are you okay?

DAVID: Yeah. It was Jim.

ME: From down the street? What the hell?

DAVID: He’s Patriot’s Alliance.

ME: WTF is that?

DAVID: I guess some new initiative to keep us “safe.”

ME: Right. “Safe” from people like me. Wait. They’re the ones using PatriotAPP to snitch on their neighbors, right? Assholes.

DAVID: He didn’t see that it was you. I told him it was Ashley. That we ran because the flashlight freaked us out, we thought he was a serial killer or something. I think he believed me. He gave me this bro pat on the back. It was gross.

ME: Will she back you up?

DAVID: She better. She’s my lab partner now, so I’ll sabotage every damn experiment if she doesn’t.

A fireball grows inside my chest. Of course he was going to get a new lab partner when I left school. Of course his life was going to continue. I’m so filled with jealousy that Ashley—mild-mannered, sweet-since-forever Ashley—gets to sit next to David for an entire hour at school without having to risk anything. I want to throw my phone to the ground, stomp on it, and crush it into tiny bits of glass and metal. But what’s the use in complaining about how unfair life is? It’s always been unfair to someone, somewhere. Now, I guess, it’s my turn.

DAVID: Layla?

ME: Here.

DAVID: I love you.

ME: I know.

DAVID: I’ll come by after school tomorrow if I can. Okay? Sweet dreams.

ME:

What I want to text:

When I look up from my phone, I see that my parents have slipped into the kitchen. I can hear them pulling dishes out of the cupboard and setting the table. I run upstairs to put my phone away. No phones at the dinner table in the Amin household.

I hurry back down and find my parents already seated in the dining room. I take my usual chair, the gray tweed perfectly molded to the shape of my body. No one says a word. My dad catches my eye for a momen. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...