- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

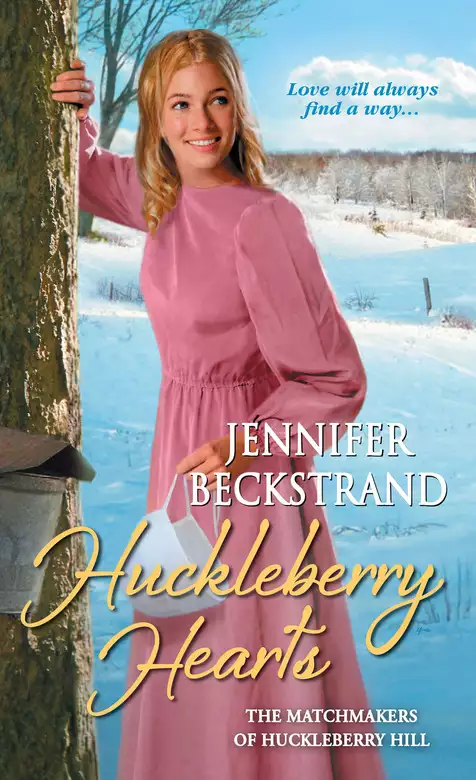

Synopsis

Though Cassie Coblenz left her Amish community to go to college, her mother and father's farm will always feel like home. It's the ideal place for an extended study break-at least until her grandmother's handsome Englisch doctor becomes a regular distraction. Zach Reynolds is the kind of heartbreaker Cassie has learned to avoid, no matter how charming he may be.

Unlike every woman Zach has met in recent years, Cassie doesn't fall at his feet. Strong, generous, beautiful within and without-she's everything he could want. Yet the gulf between them deepens when a tragedy shakes his faith. Now the good doctor has one goal-to become a man who could be worthy of Cassie's love.

Release date: November 24, 2015

Publisher: Zebra

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Huckleberry Hearts

Jennifer Beckstrand

“That’s good news,” the doctor replied. “My maternal grandfather was as bald as a cue ball.”

Anna sat on the exam table with one shoe off and one shoe on, knitting a baby blanket for the newest arrival in the Helmuth family, a baby daughter to her grandson Aden and his wife Lily. Anna’s husband Felty sat next to her with a gift box in his lap.

The young, handsome doctor with the slightly crooked nose perched on his rolling padded stool, carefully examining the bottom of Anna’s foot, and that was why she had such a good view of the top of his head. He worked his thumbs around the edges of the black spot the size of a quarter on the pad of her foot. She squirmed and tried not to drop a stitch while he poked at her.

“Sorry, Mrs. Helmuth,” the doctor said, applying firmer pressure so as not to make Anna jump out of her skin.

“Call me Anna. We Amish don’t go by ‘Mister’ and ‘Missus.’”

One side of the doctor’s mouth curled upward even as his eyes danced with good-natured humor. “Sorry, Anna.”

His smile was one of the reasons Anna was considering him as a match for her granddaughter. Cassie needed a pleasant young man who would make her laugh and wasn’t afraid to be laughed at. He had good teeth and a full head of hair, which made it more likely that Cassie would take a second look, and although Cassie wasn’t Amish anymore, she needed a godly husband more than anything else. The doctor had a way about him that told Anna he was a man of God, deep down.

Anna’s knitting needles clicked in an easy rhythm born from years of practice. “You’re not married, are you, Doctor?”

Felty drummed his fingers on the top of the box in his lap. “You asked him that same question at our last appointment, Banannie.”

Anna raised her eyebrows at her husband. “It’s been two weeks. I’m just making sure his situation hasn’t changed.”

Dr. Reynolds chuckled softly even as his fingers probed the bottom of Anna’s foot. “Nope, not married.”

“And what about a girlfriend? Do you have any girlfriends?”

“No girlfriend.”

Anna winked at Felty as her smile grew wider. “You must be wonderful lonely yet,” she said, starting a new row of stitches on her blanket.

The doctor let Anna’s foot slip from his grasp and scooted over to the cart that held his computer. “I don’t have much time for a social life. The hospital kind of owns me until I finish my residency. I live in a one-bedroom apartment with an ancient sofa and a turtle named Queenie. I don’t get out much except to come to the hospital.” He looked up from his computer long enough to give them a genuine smile. “But I don’t mind. I’ve wanted to be a doctor for as long as I can remember, and I get to treat good people like you. You are the first Amish folks I’ve ever met.”

“It’s gute you met us first instead of David Eicher,” Felty said. “He’s a hard pill to swallow.”

Anna nudged her husband with her elbow. “Now, Felty. Be careful what you say. David’s daughter is married to our grandson.”

The doctor looked like he was doing important work on his computer and she hated to interrupt him, but she had to know a few things before committing to him altogether. “Do you like children, Doctor?”

“Children? I love ’em. I want a whole passel of kids someday.” His lips curved as he typed away at his computer. “Which is probably why I don’t have a girlfriend. Talk of kids tends to scare women off.”

“Not if you’re Amish. We’re determined to multiply and replenish the Earth.”

“Single-handedly,” Felty added with a twinkle in his eye.

“Now, Felty.” Anna looped the yarn around her needle and eyed Dr. Reynolds. “Are you a hard worker, Doctor?” Her mamm always used to say that being a hard worker was the best quality a son-in-law could possess.

The doctor stopped typing long enough to consider the question. “I hope so. You can’t survive medical school without knowing how to work hard. My family owned a cherry orchard growing up. I used to work in the orchards with my dad. In the spring I pruned trees until I thought my neck would fall off. In the summer my brothers and I memorized scriptures while we picked cherries.”

“You memorized scripture?”

The doctor sprouted a crooked, unnatural grin and nodded.

That was all she needed to hear. God had put the doctor in Anna’s path, and Anna wasn’t about to waste the opportunity. There wasn’t even time to consult Felty. She had to act fast.

The doctor rolled back to the exam table and took Anna’s hand in his. Sympathy flooded his expression. “Mrs. Helmuth—”

“Anna.”

“Anna, I’m afraid I have bad news. We got the results from the biopsy we did at your last visit. That black patch on the bottom of your foot is cancer. Melanoma. It will have to be cut out.”

Anna furrowed her brow. “Does this mean I need to come back?”

Dr. Reynolds nodded gravely. “Several times. We’ll have to cut out the bad part of the skin, and if it’s deep, you’ll need a skin graft. Someone will have to come to your house several times a week to change the dressing and check the site for infection.”

Anna burst into a smile. “So we’ll be seeing a lot of each other.”

The doctor raised an eyebrow. “Not exactly the reaction I expected.”

“God moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform.” Anna deposited her knitting in the canvas bag next to her, slid from the table, and took the box from Felty’s lap. “You’ll be the one operating, won’t you?”

“I could do it, but I’m on my dermatology rotation right now. You might want the plastic surgeon to do your skin graft. I’ve only done six weeks of plastic surgery.”

“Stuff and nonsense. You’re being humble.” Anna pursed her lips and turned to Felty. “Another wonderful-gute quality in a husband.”

The doctor’s lips twitched. “I assume you want someone to operate on you, not marry you.”

Anna pinned the doctor with the look she usually reserved for naughty grandchildren, complete with the twinkle in her eye. “I don’t want to marry you, Doctor. Felty and I have been very happy for sixty-four years.”

“I’m glad to hear it,” Dr. Reynolds said.

“But I’ll only agree to the surgery if you do it,” Anna added, standing firm so that not even a team of Percheron horses could move her.

A grin played at Dr. Reynolds’s lips. “I’ll have to check with Dr. Mann first, but it should be okay.”

Beaming like a lantern on a dark country road, Anna handed Dr. Reynolds the box. “I made these especially for you, Doctor. I know you won’t disappoint me.”

Dr. Reynolds opened the box and pulled out the navy blue mittens that went with the fire-engine red scarf and the red and blue beanie Anna had knitted, also in the box. “These are for me? Why would you knit a pair of mittens for me?”

Anna grinned. It was always gute to keep potential suitors a little off balance. “There’s a beanie and scarf to go with it.”

“It’s an extraordinary gift for someone you barely know.”

“My grandmotherly talents haven’t led me astray yet. You’re the one I’ve chosen to receive the special beanie.”

The doctor looked as if he didn’t quite know how to argue with that. Smiling, he picked up the red and blue beanie and stretched it onto his head. It fit perfectly over all that thick hair of his. “Thank you. It’s very kind. Knitting reminds me of my mother.”

“I want you to feel warm and cuddly when you think of the Helmuths.”

Dr. Reynolds grinned as he wrapped the scarf around his neck. Anna had made it extra long. She didn’t want a stumpy scarf to be the reason he wouldn’t marry her granddaughter.

“Just in time for the coldest days of winter,” he said.

Anna was sure he would have put on the mittens too, if he weren’t still working on the computer. He finished whatever he was typing, took Anna’s hand, and guided her to sit in one of the soft chairs. Felty, bless his heart, waited on the exam table—probably keeping it warm in case she needed to sit there again.

The doctor, with his beanie and scarf, rolled his stool directly in front of Anna. “I don’t want you to worry about this. There’s no reason we shouldn’t be able to get all the cancer during surgery. You’re going to be just fine. And have a killer scar on the bottom of your foot.”

Anna waved her hand in the doctor’s direction. “Oh, I’m not worried. The good Lord has a purpose for everything. Isn’t that right, Felty?”

“Yes, it is.”

She patted the doctor’s hand. “But if you’re worried about it, we should pray together. God will comfort you better than even my beanie can.”

A shadow flitted across the doctor’s face. “I’m not worried. You’ll be fine.”

Anna didn’t especially like that expression. “You’re uncomfortable praying?”

“I suppose I am.”

“But you said you used to memorize scriptures.”

“I did. Out in the orchard.” The doctor lowered his eyes. “That was a long time ago.”

Anna scrunched her lips together. “Oh, dear.”

Dr. Reynolds swiped his hand down his face. “The truth is, Mrs. Helmuth—”

“Anna.”

“Anna, God and I aren’t on speaking terms, but if you want someone to pray with you, I can call Marla. She’s one of the nurses, and she goes to Mass every Sunday.”

Cassie might not have been Amish anymore, but she still needed a godly husband, and someone who didn’t talk to God would not be a godly husband. How could Anna have been so mistaken about this one? He seemed like such a nice boy. And ach, du lieva, she’d already given him the carefully knitted beanie and scarf. And mittens! Mittens were no small thing.

“Oh, dear,” Anna said again. “Felty, I’m afraid I’ve cast my pearls before swine.”

“No such thing, Annie.”

Dr. Reynolds cracked a smile. “Am I the swine?” He pulled the beanie off his head, and wisps of his sandy blond hair stuck straight into the air. “If you’d rather offer this to someone more religious than I am, I completely understand. You had no idea what my relationship with God was before you gave it.” His expression almost melted her heart. He truly held no hard feelings whatsoever. Maybe there was hope.

What kind of person would she be if she took back a gift simply because the young man might be unsuitable for her granddaughter? “Of course not,” Anna insisted. “Even if you are a swine, I gave that beanie freely. I want you to have it.”

Dr. Reynolds chuckled as his eyes danced with amusement. “I guess I’m not used to the Amish customs yet.”

Anna wrung her hands. “Oh, dear. I didn’t mean to call you a swine. It’s just an expression.”

The doctor patted her hand reassuringly. “I know what you meant. And if it makes you feel better, you’re not the first woman to call me that.”

Felty always seemed to be able to get to the heart of the matter. “So you don’t believe in God?”

Dr. Reynolds frowned in concentration. “I’m not sure.”

“That’s better than a ‘no,’” Felty said.

Anna tapped her finger to her lips. “So your faith is wavering, but not altogether extinguished. Felty can work with that, can’t you, Felty?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, Annie.”

“I mean that there’s still hope for Dr. Reynolds,” Anna said.

The doctor lowered his head to hide another grin. “Probably not.”

“Just you wait,” Anna said, nodding at the good doctor who’d misplaced his faith. “By this time next week, your faith will bloom like a cherry tree in springtime.”

The doctor cocked an eyebrow. “What’s so special about next week?”

Cassie was what was so special, of course, but Anna couldn’t very well ruin the surprise. The doctor would take to Cassie like a fruit fly took to a mushy apricot. And Lord willing, he’d find his faith again.

Maybe the beanie was in the right hands, after all.

Weaving wildly from side to side was not usually the way Cassie Coblenz liked to drive, but it was the only way she managed to get up Mammi and Dawdi’s hill in “The Beast.” The Beast was what she affectionately called her 1993 Honda Accord. Affectionately, because that car, which she had scraped together every last dime to buy, had seen her through five harsh Midwestern winters, had nearly 240,000 miles on it, and hadn’t complained about anything, even when Cassie drove it all the way to New York City to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mammi and Dawdi’s hill proved to be quite an adventure. The roads were plowed, but once Cassie ventured off the pavement and onto the lane that climbed up Huckleberry Hill, the way became icy and nearly impossible to navigate. A horse-drawn sleigh would have done much better than a car.

Cassie finally made it to the top of the hill and pulled The Beast in front of Mammi and Dawdi’s house. There it was, just like she remembered it as a child: the wide covered porch with no chairs to sit on, the kerosene lamp that hung on a peg just outside the front door, the large kitchen window that faced the front of the house so that Mammi could see everybody who came up the hill.

Cassie couldn’t remember a time when Mammi hadn’t run out of the house to greet her when she came for a visit. Mammi wanted everyone to feel welcome and loved before they even set foot in her house.

Cassie turned off the car, closed her eyes, and leaned back against the headrest. She needed a place where she could catch her breath for a minute, a place where she didn’t feel pushed or pulled or bullied or stretched.

Mamm would be disappointed that she had chosen Mammi’s house instead of her own home to stay, but her mamm was one of the worst offenders in the pushy department. At Mamm’s house, Cassie lived with a constant headache right between her eyes.

Mammi and Dawdi never lectured her about the church or baptism or hell. They just let her be.

She needed a place to be.

The tapping on the window startled her a bit. She jerked her head up and came face-to-face with Mammi grinning at her from the other side of the window. Of course Mammi would come out to greet her. She had the big kitchen window, after all.

Mammi stepped back so Cassie could open the car door. She jumped out and threw her arms around her little Amish mammi. Dawdi stood taller than the average Amish dawdi, and most of the Helmuth children and grandchildren had inherited their height from him, but Mammi was a puny little thing, no taller than five feet on a good day. Cassie wouldn’t trade her mammi for all the paintings in the Louvre, but she was glad she’d gotten Dawdi’s height. She clocked in at five-eight without heels.

Mammi gripped Cassie tightly around the waist. “Cassie, Cassie, Cassie. This is the best day in the whole world. We are overjoyed that you would spend your summer vacation with us.”

Cassie giggled. It was January sixth and the temperature couldn’t have been more than twenty-five degrees. Somewhere along the way Mammi had gotten her wires crossed. Summer vacation was a long ways away. “Well, winter break anyway,” Cassie said.

Mammi’s eyes twinkled like stars in the Big Dipper. “You know what I mean. This is your vacation, isn’t it? You’ll get to relax?”

“I’m supposed to be studying for the GRE, but I’ll have plenty of leisure time. I don’t really want to relax, though. I want to spend plenty of time with you and Dawdi, and I want to bake bread and fill the coal box and milk the cow. All the things I’ve missed since I’ve been away.”

Mammi’s whole face wrinkled when she smiled. “You want to do chores?”

“I want to do Amish things. There’s something so calming about working with my hands and disconnecting from all the electronics.”

Mammi winked. “Don’t let your mamm hear you talk like that. Her hopes will soar to the moon.”

“I won’t,” Cassie said in an exaggerated whisper. Mamm was not all that pleasant when she got her hopes up. She wasn’t all that pleasant to begin with. “I’ll be here to drive you to the hospital and help you recover from surgery and everything. Leave it all to me.”

“I will,” Mammi said. “I’ll leave everything to you and the doctor.”

“Is he a good doctor? Do you feel comfortable with him?”

A furrow appeared between Mammi’s eyebrows. “There was some confusion about that at first, but Felty thinks we should give him a chance. I’ve already given him the gifts, and I don’t think it would be right to back out now.”

“I’m sure everything will turn out just fine.”

Mammi bloomed into a grin. “If you’re sure, then I have complete confidence. You always did have a sense about these things.”

“I got it from you.”

Mammi balanced on her tiptoes and planted a kiss on Cassie’s cheek. “Cum reu. Let’s get you out of the cold. Felty paid special attention to the fire this morning so the house would be toasty warm when you got here.”

“Do you care if I walk around outside first? I kind of want to breathe in the whole place before I come in.”

“Would you like some company? I wore my galoshes.”

“Of course.”

Arm in arm, Cassie and her mammi trudged toward the barn. Their breath hung in the air as their boots crunched through the snow. Mammi pointed to the house. “We got a new roof in September. Your cousin Mandy’s husband Noah did it for us. I think he and Mandy fell in love on that roof. Or maybe they fell in love in the barn. He’d go in there and lift heavy things, and she’d go in there and watch him.”

Cassie opened the barn door, and the familiar, homey scent of hay and livestock and damp air filled her nose. She loved the pungent smell of a barn. It made her feel as if she were home.

She was as close to home as she would ever get.

Mammi pointed out the pulley system that Mandy’s husband Noah had rigged up to lift hay into the loft. “He got tired of hefting it up there by hand.” She talked about the horse and the chickens and cow. “If you milk the cow,” she said, “be careful. Iris likes to stick her tail in the milk pail. She’s ruined more than one perfectly good bucket of milk that way.”

Cassie laughed. Cows could be ornery. She and Norman used to sing to them to coax them to cooperate during milking. Norman didn’t have much success with the singing—his voice was too loud—but the heifers seemed to like it when Cassie sang lullabies.

A pit grew in Cassie’s stomach when she thought of her brother Norman. No one in her family had been happy about her leaving the community, but Norman and Mamm had been the most vocal about it. Being two years older than she, he felt it his duty to keep her on the straight and narrow path. He took it personally when she decided to stray.

They left the barn and walked under the beautifully pruned peach trees, then the empty trellises that would be laden with grapevines in the summer.

Mammi laid her hand on a plastic barrel that sat against one wall of the barn. “Your cousin Aden built us this composter. You put kitchen scraps in and nice black soil comes out in a few weeks. He says we’re helping to save the Earth, which seems like a good project. It feels like a bigger job than just Felty and I can do, but we’re doing our best. We wouldn’t want the Earth to die because we didn’t do our part. And we wouldn’t ever hurt Aden’s feelings.”

“Aden is passionate about the environment.”

“But I don’t think everybody is doing their part,” Anna said. “Aden’s own father-in-law refuses to get a composter. And if you mention ‘recycling’ to him, he holds his breath and turns blue. He’s not going to save the Earth with that attitude.”

As they walked back to the house, Cassie’s gaze turned down the little path that led to the other side of the hill where the huckleberries grew. Some of her fondest memories were of huckleberry-picking frolics. “Did you get a lot of huckleberries this year?”

“Jah. Every year.”

“I’m sorry I missed it.”

“February is maple sugaring time. You can help with that if you like.”

“I’d love to. That’s almost as fun as huckleberry season.”

Cassie walked to her car and pulled her purse and large blue suitcase from the backseat. “Thank you for letting me stay.”

“Nae, thank you. We are looking forward to a very entertaining winter.”

“I don’t know how entertaining I’m going to be, but I’ll do my best to be a good houseguest.”

Mammi stopped in her progress up the porch steps. “Nae. You’re not a guest. Guests are acquaintances that you put out the good towels for. You are our granddaughter and closer to our hearts than any guest could ever be. But I’ll still put out the good towels for you.” She patted Cassie on the cheek. “You are family. Never forget that.”

Cassie’s eyes stung with tears. It had been so long since she felt at home anywhere. It was a sure sign she desperately needed a break from the real world when one kind word from Mammi nearly made her melt into a puddle of water right here on the porch.

Mammi hadn’t been kidding about the warm house. They were hit by a wall of heat as soon as they walked into the kitchen. Dawdi had probably been feeding the stove in the cellar all morning.

The kitchen table to her right was crowded with platters of cookies. “What’s all this?” she asked.

Mammi, always genuinely happy, seemed to turn on a sort of fake cheerfulness in her voice. “We can’t celebrate your homecoming without eats.”

Cassie set her suitcase on the floor and took a deep breath. The great room was just as she remembered. Even Sparky, Mammi’s curly white dog, didn’t seem to have moved in the last four years. She lay asleep on the rag rug in front of the sofa. Dawdi’s recliner sat in the place it had been for twenty years, except it wasn’t the same recliner. He’d probably rocked the old one down to dust.

A new LP gas stove sat where the trusty cookstove used to be. More than once over the years, Cassie had heard Mammi swear by that cookstove. She had always put a stop to any talk of getting a new one because she felt more comfortable cooking on the old one. Not that anything was cooked well on the old cookstove—Mammi was famous for being the worst cook in Wisconsin—but Mammi liked it better, so Dawdi hadn’t been inclined to get her a new one. Cassie smiled to herself. Dared she hope that the new stove had improved Mammi’s cooking? She might volunteer to do all the meals while she stayed here. She could only gag down so much bad food before she was sure to develop some sort of digestive condition.

Mammi saw where Cassie’s gaze fell. “The new stove was Felty’s idea. He used it to lure Noah Mischler into the house so he would fall in love with Mandy. I’m willing to make any sacrifice if it will help one of my grandchildren find love.”

Cassie smiled and wondered how someone could be lured into the house with a stove. Dear Mammi. She was legendary for her cooking, her knitting, and her matchmaking. Thankfully, there was no risk of Cassie becoming Mammi’s next victim. Mammi only matched her Amish grandchildren with good Amish mates, and Cassie wasn’t Amish anymore. She was safe.

Dawdi came bounding into the great room with the energy of a sixty-year-old. He never seemed to tire. “Well, bless my soul, it’s my long-lost granddaughter.” He drew Cassie in for an embrace, and the unruly hairs of his beard tickled her chin.

“Hi, Dawdi.”

He nudged her to arm’s length. “Let me have a look at you. You cut your hair. I like it.”

“Mamm won’t,” Cassie said, taking a deep breath in anticipation of Mamm’s reaction to the chin-length hairstyle she’d been sporting for over a year.

“Now, who says she won’t like it? She’ll love it.”

Cassie kissed Dawdi on the cheek. “It’s wonderful gute to be here. Thank you for letting me come.”

“The Lord’s timing is perfect,” Mammi said. “How often do I get melanoma on my feet?”

“I’m glad I could be here.” Cassie took off her coat. “Can I help make dinner?”

Mammi looked at Dawdi, and Dawdi eyed Mammi. “You didn’t tell her?” Dawdi said.

Mammi shrugged. “I didn’t want to spoil our lovely stroll.”

Dawdi smoothed his beard, a sure sign he mulled over something serious. “Cassie, I have some good news and some bad news. Your mamm caught wind that you would be arriving today, and she’s invited herself to dinner.”

Cassie’s smile suddenly felt as if it were plastered onto her face. “Is that the good news or the bad news?”

Dawdi thumbed his suspenders. “Jah.”

She sank into one of the chairs at the table. “I had hoped to have a little more preparation before I saw Mamm.”

Mammi plopped next to her and patted her hand reassuringly. “I tried to think of a good fib, but your mamm caught me off guard. She even insisted on bringing the food. I couldn’t think of a good way to say no. Sometimes it’s tricky being the mammi. I’m always getting myself into trouble.”

“It’s all right, Mammi. I knew I’d have to face them sometime. I was just hoping for a good night’s sleep first.”

“Your mamm loves you very much,” Dawdi said in an attempt to make her feel better.

Cassie slumped her shoulders. “I know. She can’t help herself. When we get together, she feels a certain responsibility to lecture me on the evils of the outside world. I just wish she weren’t so ornery about it.”

“She thinks you’re going to hell,” Mammi said. “That makes her a little testy.”

Even though her lungs felt as if The Beast were parked on her chest, Cassie couldn’t help but giggle at Mammi’s nonchalant attitude about where Cassie would or would not end up in the afterlife. “Everybody in the community thinks I’m going to hell. It kind of puts a damper on things.”

“I guess it does,” Dawdi said, pulling out a chair and joining them at the table.

Mammi shook her head. “I don’t think you’re going to hell, dear.”

“I know,” Cassie said. “But I don’t understand why. You are two of the most dyed-in-the-wool Amish I know.”

Dawdi snatched a cookie off one of the plates and took a bite. “There are eight billion people on this planet yet, and I have a pretty hard time thinking that God created all those children just to send them to hell because they’re not Amish. My job is to live my life the best way I know how and leave the judgment to Him.” He leaned back in his chair and pushed his lips to one side of his face.

Cassie laughed. “Be careful, Dawdi. That’s pretty radical talk.”

“I usually keep it to myself.”

“Felty, you are so smart,” Mammi said. “I had no idea there were that many people in the world.”

“No smarter than you are, Annie. You know how to make gingersnaps without a recipe. And they’re so tasty.”

Cassie eyed the gingersnaps on the plate. They looked like maple-brown golf balls. How bad could they be? Mammi would be pleased as punch if she ate one. It made Mammi so happy to see people enjoying her food, or rather pretending to enjoy it. No one but Dawdi actually enjoyed Mammi’s cooking.

The second Cassie picked up a cookie, she knew it was a mistake. Not only was it the size of a golf ball, it was as hard as one too. She’d break her teeth if she tried to bite into it.

Dawdi’s teeth scraped against his cookie like fingernails against a chalkboard.

“Have you got milk, Mammi? I like to soak my cookies in milk to make them soft.” Would Mammi get suspicious if Cassie’s cookie was still soaking at midnight? That thing would never, ever get soft.

“Of course I’ve got milk,” Mammi said, going to the fridge and pouring Cassie a generous glass. “Iris is a good milker.”

Cassie took a sip of creamy milk before dropping her cookie into her glass. The milk made her feel somewhat better. She could handle Mamm okay. Better today than dreading a meeting later. “I’m glad Mamm is coming. I’ve missed her. It will be nice to have a chat, just the four us.”

Dawdi leaned forward and took another bite of his cookie. “I have some good news and some bad news.”

Cassie’s heart sank.

“Norman is coming and so is Luke.”

Cassie made an attempt to sound more enthusiastic than she felt. “Well. That will be nice. I haven’t seen the baby for a year.”

Cassie had seven siblings, all but one older than she. Her oldest sister Sarah married before Cassie had even been born. Sarah’s daughter Beth, Cassie’s niece, was older than Cassie.

Norman and Luke were the siblings closest in age to Cassie. Norman was two years older and Luke just a year younger than Cassie. Luke tended to keep his opinions to himself, but Norman was more than happy to call Cassie to repentance on a regular basis. He was one of the reasons she came home so infrequently.

Mammi tilted her head as if she were listening to something that no one else could hear. “They’re coming.” She leaped to her feet and went straight to the door. “We should probably move all those goodies so the table can be set.”

Heedless of the cold, Mammi opened the door and charged outside to greet the new group of visitors. Cassie self-consciously smoothed her hair before helping Dawdi move the seven plates of rock-hard cookies to the kitchen counter. Luke would probably eat them. Luke ate

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...