- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

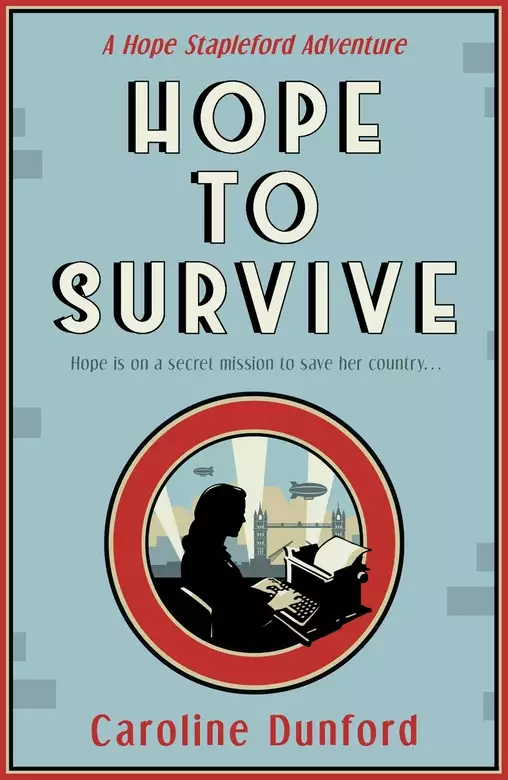

The second Hope Stapleford adventure is an exciting spy thriller in which secret agent Hope embarks on a dangerous mission to save her country...

It is 1939 - war has been declared and spymaster Fitzroy wastes no time in preparing his goddaughter, Hope, for a secret mission. As Euphemia Martins' daughter, Hope has the potential to be one of British Intelligence's greatest agents, but when she is ousted from an all-male think tank and relegated to the typing pool, even she starts to doubt herself.

Meanwhile, Hope's rebellious friend, Bernie, announces her engagement to a man Hope does not trust; Harvey, Hope's only asset, has vanished; and, most awful of all, Hope fears that her father is dying. Then comes Dunkirk and the threat of invasion intensifies. To her surprise, Hope is sent to a secret base, where she joins a group of auxiliary units that are expected to fight to the death should invasion occur. Fearing for her life, she must confront Nazi sympathizers among the country's elite secret service before she can learn who to trust...

(P) 2021 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: February 18, 2021

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 256

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hope to Survive

Caroline Dunford

We were sitting in one of the offices my godfather didn’t have. The room was neat, business-like and only slightly bigger than his huge leather-topped desk. It was situated on the fourth floor of a Georgian building which had a lovely view over the park. My godfather, Fitzroy, sat in one of those rotating captain’s chairs and swivelled slightly from side to side. By the window was a leather wing-backed chair, angled to make the best of the view, and by the fire was a medium-sized dog basket with a white puppy snoozing in it. Bernie and I sat in front of the desk in two upright wooden chairs, clearly chosen for their lack of comfort. Bernie, wearing a ridiculously short skirt that practically showed her stocking tops, was sitting with her legs crossed, swinging the uppermost one annoyingly and repetitively. My godfather passed her a newspaper and a pen.

‘What do you expect me to do with this?’

‘The crossword,’ said my godfather, and ignored her from that point on. He picked up the papers I had given him and then dropped them on his desk again. ‘None of these will do, Hope.’

‘We have looked,’ I said.

Without glancing up, Bernie said, ‘Hope doesn’t want a large apartment. She thinks I would hold parties.’

My godfather raised an eyebrow at me. I shrugged somewhat helplessly.

‘So, money isn’t the issue?’ he asked.

I leant over and took back one of the papers. On it I wrote an amount with Bernie’s Budget written above it. It was neither a small sum nor an outrageously large sum. In fact, it seemed to me to be the perfect amount for a half-share of a two-bedroomed flat somewhere respectable. Currently, Bernie was outstaying her welcome at the American Embassy where her father had been Ambassador, and I was staying at my club, The Forum. The real reason we were not yet ensconced in a nice little flat was because my godfather hadn’t approved of anything we had found.

While Bernie was not related to my godfather, I wouldn’t have put it past him to cause her some trouble if he felt she was leading me astray. However, I had my own more than adequate resources. I could do whatever I liked. In fact, my father would have strongly approved of my ignoring Fitzroy’s advice. Except I knew he generally gave very good advice. Even if it didn’t always look like the wisest course, his nudges, in the case of my investments and other aspects of my life, had always proved acutely provident. But then I knew that Fitzroy was a senior member of the British Intelligence Service. And I knew this because he had recently recruited me.

‘I suppose you could try this one?’ he said, opening a drawer and passing me a property listing. I scanned through the details and recognised it was perfect in every way. Two bedrooms, a social area, a well-equipped kitchen so we could cook if we had to, a decent bathroom, and even a small balcony off the living space. It was in Pimlico, Belgravia Road, on the edge of Warwick Square. One of those nice, white-brick, terraced buildings that had once been townhouses but had, over time, been carved up into separate flats. The moment I saw it I knew it was the place he had intended us to have all along. I passed the paper to Bernie, who dropped the newspaper on the floor.

‘Ooh!’ she said. ‘Sunset cocktails on the balcony!’

Fitzroy’s expression grew somewhat pained and he shifted in his chair, focusing his attention on me so that Bernie was only on the very periphery of his vision. ‘What do you think?’

‘Perfect,’ I said. ‘How very clever of you to find exactly what we wanted.’

The lines around his eyes crinkled slightly and he gave an almost imperceptible nod.

‘Is there a telephone number to call?’ I asked. ‘Perhaps we could give them a quick ring and see if we could visit later today. Bernie? There’s a telephone in the lobby of that little hotel we passed on the way here, the one you wanted to go into for a quick cocktail when you thought we were much too early?’

‘Oh, good idea,’ said Bernie, standing. ‘Thank you ever so much . . .’ She floundered, and offered her hand to Fitzroy. ‘Well . . . I’ll see you in the cocktail bar, Hope.’

A short period of time after she had closed the door behind her, we saw her in the street, hurrying along as fast as she could in her tight skirt. I sat back down in my chair and relaxed. ‘You know she has no idea how to address you,’ I said.

Fitzroy gave me a half-smile. He turned and opened the cupboard behind him. ‘A small brandy?’ he said, pouring me one before I could protest. ‘You do know, don’t you, that the whole idea behind cocktails was to disguise the taste of the awful liquor they used during Prohibition? Mucky stuff. Do you like this office? The view is excellent.’ He remained by the window, watching Bernie wiggling her way along the street. ‘It isn’t mine, but I’m thinking of keeping it for a while.’

‘Bernie,’ I said, in an attempt to bring the conversation back on track. ‘I have to tell her something. Should she refer to you by your military rank? Should she call you Eric, like Mother does? Or should she call you Fitzroy?’

‘She knows I’m your godfather, that should be enough. If she wants to address to me directly, which I am disinclined to encourage, she can address me by the rank I am wearing at the time.’

‘Which will change?’

‘On occasion.’

‘Along with the uniform, no doubt,’ I said, ‘and I will be able to offer no explanation. She is more observant than you think.’

Fitzroy gave a slight snort.

I sighed and took a small sip of brandy. It was excellent, so smooth it felt honey-like. ‘You had that property in mind all along, didn’t you?’

‘Of course. It had to be properly assessed and vetted. But your little friend needs to believe I came across it by accident. You can make up some story – the property of a great-aunt of mine, or some such thing.’

‘Do you have a great-aunt?’

‘No, you’re probably right. I’m too old for a great-aunt. Keep forgetting my age. You can make it an aunt. And yes, I believe I do still have some of those.’

‘Have you really become Bernie’s guardian?’

Fitzroy winced. ‘No, not exactly. I have made an agreement with her parents that I have a . . . err . . . “watching brief”. I don’t believe they would have left her behind otherwise, and you certainly can’t live on your own.’

‘So, I owe you another debt of thanks?’

‘My dear Hope, you owe me nothing. I am simply doing my best to be a decent godfather to you.’

‘I think my father thought that your involvement would entail little more than postal orders and Christmas cards.’

Fitzroy finished his brandy with a flourish and set down his glass lightly. His skin didn’t flush. My mother had told me he had a head for spirits. (What she had actually said was, ‘For heaven’s sake, never try to out-drink your godfather. You’ll end up under the table and he’ll hold it over you for ever.’)

Fitzroy coughed. ‘Yes, well, your father, decent fellow that he is, has never exactly been a close acquaintance of mine. He’s often misjudged me.’ He cast his eyes down at that, in mock sadness. I half suppressed a giggle. When he looked up, all trace of humour was gone. ‘Are you sure, Hope, that you want to come and work for me? It’s going to be damned difficult.’

‘I thought we had already agreed?’

‘Your mother didn’t believe me either when I warned her. She found out the hard way. I’m conflicted about watching you go through the same process.’

‘I can never predict what you will say next.’

‘Thank you,’ said Fitzroy. ‘I appreciate that.’ He took a deep breath. ‘You came in to see me today as my goddaughter, and I have treated you as such. When you attend me as one of my people, I will behave very differently.’

‘Of course. I don’t expect special treatment,’ I said.

‘Good. I couldn’t give it to you, even if I wanted to. We probably won’t meet here. I’ll let you know where and when. I’d like to have had some time, privately, to get you up to speed on the various sections, but I doubt Herr Hitler will afford me the courtesy. You’re as well skilled, if not more so, than many of the recent recruits, but you haven’t exactly been trained through official channels. People will want to test you. You’ll have a rough time of it.’

‘My mother coped, didn’t she?’

‘Admirably, but it was a different time, and her personality, well, it’s . . .’

‘More robust than mine?’ I finished.

‘More passionate,’ corrected my godfather. ‘You are more like me, a watcher and a schemer.’

‘You seem to have done all right.’

‘I, my dear, am a man, and have all the advantages thereto pertaining. There are precious few of us who appreciate and value how much women can offer the Service.’

There didn’t seem to be much I could say in response to this. I waited a while to see what Fitzroy would say next. He put his glass on the side. When he sat back down at the desk, he leant forward, resting on his elbows and steepling his fingers. I waited while he watched me. Despite having spent a lot of my early childhood sitting on his lap and, I am told, tugging at his moustache, I found the figure before me daunting. I knew better than to look away, and eventually I gave in and spoke

‘How’s Jack Junior?’ I asked, glancing down at the puppy, glad to have an excuse to avoid the scrutiny of his gaze.

‘Just Jack,’ said Fitzroy, snapping my attention back to him.

‘I’m sorry.’

Fitzroy made a sound halfway between clearing his throat and a cough. It was the closest he came these days to expressing emotion. ‘Do you think you’ll be all right living with Bernie? She’s a very noisy cover for you, but then, I suspect, if she sees or hears anything she shouldn’t, you’ll be able to tell her she was drunk and imagined it.’

‘You make her sound awful.’

‘I don’t believe she’s currently doing herself any favours. I’m hardly running with the younger set, but even I’m hearing things . . .’ He trailed off, leaving it to my imagination to finish the sentence.

‘You hear everything,’ I said, earning myself a fleeting smile. Then my godfather sat further forward and put his arms on the desk.

‘Hope, my dear, I am very proud of you, and always will be.’

This time it was my turn to deflect. I looked down at the sleeping dog. ‘Are you really going to keep this office? It’s rather small.’

‘Yes, but officially it won’t exist. There are a lot of changes happening within the Service at present. A lot of people carving out their personal domains. Even I’ve been promoted.’

‘To?’

He frowned, as if trying to recall. ‘Lieutenant-Colonel,’ he said. ‘Makes me feel as if I should grow a bigger, bushier moustache and make noises like an ageing bear. At least that’s how I remember them from my youth.’

‘Congratulations.’

Fitzroy shrugged. ‘As long as I’m allowed to do my job, I don’t much care what they call me. Maybe don’t mention it to your mother, though. It’s all still a bit iffy when it comes to ranking females in the Service.’

‘I thought you said my mother had retired?’

Fitzroy shook his head. ‘She mostly withdrew from field work, but she never stopped working for, or rather with, me. In the current circumstances, she’s back on the team. One of my, I mean our, most experienced officers. I hope to keep her out of the field. She’ll be adding being a handler to her other duties. Don’t worry, I won’t put you two together. I’m aware you don’t have the smoothest of relationships. However, she could be in London a fair bit. It might give you two an opportunity to bond.’

‘But where would she stay? Do you mean she would be staying with me?’ I could feel my heart begin to race at the thought.

Fitzroy shook his head. ‘No, she has her own flat.’

‘What?’

He frowned. ‘You didn’t know? Your mother bought it a long time ago, when we were working together during the Great War. It gave her a base here to operate from.’

‘But I thought she . . . I mean, I didn’t . . . I don’t think my father knows.’ I felt myself blush for the first time. Only my mother, I thought. ‘It’s . . .’

‘You didn’t think she stayed with me, did you?’ said my godfather. ‘That would hardly have been proper.’

‘No, of course not. She’s never spoken much about that time. Before I was born. I knew she was involved . . .’

‘Very much so. Your mother is a first-class spy. Euphemia has spent her life in the service of others. Only thing the poor girl ever got to do that she enjoyed was active service.’

I got up. Unsaid between us was the knowledge that my mother had only ceased field work because of me. ‘I should go and meet Bernie.’

My godfather stood and came around the desk. I looked up at him. ‘You admire my mother, don’t you?’

He put a hand on my shoulder. ‘I am very fond of you both. Be careful, Hope. I won’t be around as much as I’d like over the next few months. All kinds of new shifts afoot.’ He handed me a business card with a single telephone number on the front. I turned it over and saw a short list of names and places. ‘Learn them, then burn it.’ He gave me a lop-sided smile. ‘It’s what you might consider my answering service on the one side. The other is . . . well, if I’m unavailable, those are contacts who’ll go to extreme lengths to help you, if need be, no questions asked. I sincerely hope you will never have to use them, but if you get yourself into a tight corner, do. But,’ he said, putting his other hand on my other shoulder so I could feel the weight of both, ‘only use them with caution, as a near-last resort.’

‘Near-last?’

‘Last resort is often too late, in my experience. If you still think the situation can be salvaged. I feel as if I am leaving you untethered. I’m not. You’re skilled, even if you’re coming in as a new recruit. It’s simply damned hard for me to remember you’re a capable young woman and not a child any more. I suspect I may be becoming sentimental in my old age. Definitely something I shall have to address.’ He lifted his hands away from me. ‘As well as what’s coming, I have family business to attend to, at exactly the wrong time. Typical of my father to make life as inconvenient as possible.’

It took me a moment to work out what he was saying. ‘Your father? Oh, I’m so sorry.’

Fitzroy shrugged. ‘Don’t be. It has raised certain complications that I must deal with, but other than that I am not affected. We were never close, and I have found myself profoundly unmoved, unless my grief is masking itself as irritation.’

I tried in vain to think of a response, failed, and bent to pick up the newspaper Bernie had dropped on the floor. I handed it to him. He glanced at it and his eyes widened. ‘Well, I’ll be blowed.’

I peered over. ‘Bernie’s very good at crosswords. She does them when she’s bored, which is often.’

‘Hmm?’ said my godfather, frowning and clearly not listening to me. ‘I shall have to tell them to make it harder . . . unless . . . no, that seems quite unlikely.’ He focused his attention on me as if waiting for me to supply an answer to the unspoken question. Again, the moment passed as I failed to find anything to say. ‘You should check in on your asset, Harvey. I’ve already had to quash one report of him acting outside the lines of the law. Tell him to get himself in order or he’s burned as an asset.’

He opened the door, effectively closing down the conversation. I stood on tiptoe and kissed him briefly on the right cheek. His face softened slightly, but he nodded towards the door. I was out on the street before I realised. I’d been so lost in thought, I hadn’t had a chance to meet Jack properly. Still, if my godfather was leaving town, maybe he would leave the puppy with us, if he considered the apartment suitable. I had a sneaking suspicion that the criteria for Jack’s accommodation would be stricter than his criteria for that of Bernie and me. And why had my mother never told my father or me about her London flat? If it was meant to be a secret, Fitzroy had given it away awfully casually. And he never gave away secrets. Did she still use it? When she said she was paying a short visit to relatives, was she actually coming here? And if she was, what was she doing?

In the small hours of the morning on 1st September, the telephone burst into life.

RING! RING!

Bleary-eyed, I sat up. Bernie would probably sleep through the angels sounding the last trumpet on Judgement Day. Our aptly named charwoman, Mrs Spring, wouldn’t turn up for a considerable number of hours yet.

RING! RING!

With enormous reluctance I crawled from the warmth of my bed.

RING! RING!

Could it actually be getting louder? Where were my slippers?

RING! RING!

I brushed under my bed with my hand but found only a cocktail glass. I pulled it out and looked at it, trying to remember how it might have got there.

RING! RING!

I padded in my bare feet across the cold marble floor of our foyer in Belgravia Road.

RING! RING!

The telephone vibrated angrily atop the small marquetry table upon which it sat.

RING! RING!

How annoying. How persistent. Likely one of Bernie’s suitors.

RING! RING!

‘Hello?’ said my godfather when I picked up the receiver. I felt positively discombobulated. All I could manage in my befuddled state was a sleepy greeting, which came out as, ‘Haaa-ooo.’

‘What’s wrong?’ he snapped. ‘Why did it take you so long to answer my call? Did you have to run all the way down from White Orchards?’

‘I was asleep.’

‘Asleep?’ Astonishment and reproach sounded in his voice.

I blinked and shook my head. ‘You sound shocked. Would you rather I was out at some seedy nightclub snorting cocaine?’

‘Frankly, I would find that more understandable for someone of your age and social status at this time of the morning. However, you’ve always been a sensible girl.’ Again, I heard that tone of reproach.

‘Is that a—’

‘Now listen. I need you to come in.’

‘This morning?’

‘No, Hope. Now. Germany has invaded Poland. This is how it’ll all kick off. God knows, we’re not prepared for any of it.’

He gave me a street name, no number, then rang off.

This then was my godfather in spymaster mode. My mother had always claimed, contrary to my experience, that Fitzroy was horribly bad-tempered, and this must have been what she meant.

I staggered, literally leaning on one wall, then the other, of our hallway as I made my way to the bathroom. The electric light gave my skin an unpleasantly sallow effect. I turned on the cold tap, which spluttered a bit, but finally delivered a decent stream. I splashed my face with water – it was stunningly cold, like slivers of ice penetrating my brain. It did the trick and I finally woke up. Fitzroy had said Germany was invading Poland. He’d said we were not prepared, and he would know. For the first time I wondered if I could handle what was coming. I felt bile rising inside me. I leant over the loo just in time and expelled last night’s supper. As Bernie had been the one who cooked it, it tasted slightly better on the way back up. I straightened and washed my flushed face, rinsed out my mouth and told myself not to be a fool.

Ten minutes later, I was writing a note to Bernie on the pad by the telephone:

Been called away. Aim to be back by dinner. If not, don’t worry – as if you would!

Have a sober day? Think of your liver.

Love H

A quarter of an hour later, due to my good fortune in catching a cab driver still on shift, I turned up outside a block of very nondescript offices. The building looked so thoroughly innocuous that I knew it had to be the right place.

I jumped out, paid the cabbie, and ran in through the rust-coloured double doors. Inside I found a small vestibule. An older man in a smart suit sat in a tiny office behind a window, sipping a cup of tea. ‘Hope Stapleford,’ I said, hoping this was enough.

‘You’re late,’ growled the man in a surprisingly deep voice. ‘ID card?’ He spoke with the clipped voice of an army man, but he was in civilian clothing. I felt very much like asking him who he was, but common sense prevailed. I was already late.

I went to hand it through the little letterbox-like grille at the bottom of the window, but he didn’t release the latch. ‘Up against the glass, please.’

I did as I was told. ‘Through those doors and up to the third floor. Room 345. Report to the Commander.’

I took the lift, which was poky and smelled of stale cigarette smoke, and it creaked and shuddered its way up to the third floor. I found room 345 easily enough. From it came the sound of male laughter and one singular basso voice. ‘Now, now, lads. We should give her a chance.’

I gritted my teeth before opening the door. I had the distinct feeling that, other than a few secretaries, there weren’t many females in this building so, the odds were, they meant I was the ‘her’ to be given a chance.

I knocked and entered. A barrage of eyes met mine. It took me a moment to separate out the individuals, but I sensed immediately that my godfather was not there.

‘Apologies for my lateness,’ I said, knowing better than to offer an excuse. ‘I am Hope Stapleford. I was told to report to this room.’

‘Miss Stapleford, who is also out of uniform,’ said the basso voice.

‘I’m sorry, Captain, but I have yet to be issued with a uniform.’

‘Look, miss, you have come to the right room, haven’t you?’ said a younger man, with a sergeant’s stripe. ‘We’re all regular army here. Don’t normally include women, unless you’re making a tea run.’

I surveyed the room quickly. It looked as if both the furniture and the men had been hastily assembled. The chairs were only similar in that they all looked office-like and uncomfortable. As well as those, an assortment of small desks and slightly larger tables filled the room. Of the men present, the Captain, tall, slightly overweight, and skirting middle age, was the only man standing. The other man who had addressed me sat on a chair, rocking backwards. He had a cheeky face, tight red curls, and as many freckles as a leopard has spots. Two men sat on the edges of desks. At the very back of the room, out of direct light, I could see the silhouette of another man leaning against the wall with his arms folded. He struck me as the figure most worthy of notice because of all of them he was the one most at ease. The others, even the Captain, displayed signs of tenseness. Jaws were set too firmly, eyes blinked too rapidly, and the two men sitting on the desks were clearly trying too hard to telegraph relaxed postures. I wanted to ask what made them all so uneasy, but I kept my thoughts to myself.

‘No, I am quite sure I am meant to be here,’ I said to the Sergeant. ‘I received a phone call from someone I trust completely, telling me to report here. Besides, I wouldn’t have even known this was an Army building without having been given the directions.’

‘Still seems a bit of a rum do,’ said the Second Lieutenant sitting on the desk. Despite a weak chin, he had a well-built physique and a fitting upper-crust accent. ‘What do you think, Captain Max?’

‘I had been told to expect a Cadet Stapleford,’ said the captain, ‘but I had no idea you would turn out to be a woman.’

I bristled at this comment, knowing from what I had overheard it was a lie, but I brought to mind my godfather’s stern warning about the regular army and respect for hierarchy.

‘Is this a problem, sir? Is there a particular reason why you require male recruits?’ I did my best to sound polite.

‘We’re an ideas group,’ said the chirpy red-haired sergeant. ‘We’ll be talking about logistics and stuff. Nothing to interest a woman.’

‘I have a degree in mathematics from Oxford,’ I said. ‘I may be of some use.’

The Captain rubbed his chin. He was still standing. A heavy frown creased his forehead. ‘Well, I suppose you might be of help with the adding-up, but we’re a high-security group. Can’t say I’m keen on having a female present. No offence, my dear, but ladies do tend to gab on a bit, don’t they?’

A number of retorts came into my head, but none of them were suitable for a so-called superior officer. Why the hell had Fitzroy sent me here, and why had he put me in as a lowly cadet? Surely I was better than that?

‘Who gave you your orders?’ asked the Captain. ‘You said you trusted them.’

Only at this point did it occur to me that Fitzroy might have sent me in as one of his people to monitor this unit, or someone within it.

‘Come on, girl. Spit it out,’ said the Captain. He looked more relaxed now. I could already picture him on his telephone afterwards, calling up someone and saying, ‘You’ll never believe this, but we’ve been sent . . .’

Fitzroy hadn’t said if I could mention his name, but common sense dictated I refrained from doing so. Besides, I only had one of his code names. I realised with growing astonishment my godfather had kept me ignorant of his real name – other than his Christian name, Eric – the whole of my life.

‘I can’t say,’ I said.

‘What!’ blurted the Captain. ‘You may be a new recruit, so I’ll overlook your insolence this one time, but you’ve been asked a question by a senior officer. Reply, or I’ll put you on a charge! How would you like that?’

The man at the back of the room stepped into the light. Middle-aged, but clearly fit, he had short greying black hair, dark blue eyes, and was wearing unmarked fatigues. ‘She’s all right,’ he said.

The room turned as one to look at him.

The Captain spluttered, ‘You mean you know her, Cole?’

‘I know who she is,’ said Cole. ‘You brought me in as a consultant, Max. Trust me on this. She’s all right. You’d be a fool to leave her making the tea,’ he added.

All eyes turned back to me with renewed interest. ‘Well, that’s quite a recommendation,’ said the Captain, sitting down again. ‘Cole tends to be rather scant when it comes to praise.’

I took this as an invitation to stay and edged further into the room. One of the men on the desks turned a chair around for me. I sat on it, my hands folded in my lap, and waited. As I did so, I mentally assessed the men in the room.

My gaze didn’t go unnoticed by Cole, who suddenly spoke. ‘Before we go any further, Cadet, give me an appraisal of the men in this room.’

I looked at the Captain, who nodded.

I started with the red-haired Sergeant. ‘You have a slight Irish lilt to your voice,’ I said. ‘You’re wiry rather than heavily muscled. I haven’t seen you move, but I would hazard that you can hold your own in a scrum. Your formal instruction goes back no further than basic training. You’re bright and alert, but your background and class have held promotion back. I could beat you in a fight.’

The Sergeant laughed and held out his hand. ‘Lewis Bradshaw. People don’t normally detect the Irish in me. My grandpappy came across decades ago. You’re welcome to challenge me any time, darlin’. I’ll be gentle.’

I gave a slight, insincere smile. ‘The Second Lieutenant is the fittest man in this room, but his arm strength is greater than that of his legs. I suspect he is a sportsman. Oxford rowing blue? Only recently joined up.’

‘Martin Wiseman,’ said the man in question. ‘Spot on. Good parlour trick.’

I didn’t smile. ‘The Lieutenant is harder to assess. Both he and Second Lieutenant Wiseman have spent some time studying – acting, I think. They have unusually good deportment, and have been overly careful not to turn their backs on the room. Probably at college together. Clearly old friends, but the Lieutenant is not a rower. He might be more of a reader. Until I see him move, I can’t comment on his physical prowess. He’s not a boxer. On the other hand, there are some fighting disciplines that leave less of a tell-tale influence on the body.’

‘Charles Merryworth,’ said the man, nodding to me.

‘And me?’ said Cole.

‘You, sir? With respect, I’d go a long way not to make an enemy of you.’

He laughed. ‘See why they sent her to you now, Max? She’s Alice’s daughter. Probably been in training all her life.’

The Captain registered who my mother was, but no one else did. I could see them fizzing with questions, but Captain Max moved things along.

In what was little more than an old office, smelling faintly of dust and polish, he told us the likely fate of the nation. ‘We’ve got a bit of a job on, lads.’ He coughed, ‘And lady.’

Everyone looked at me again. I felt like saying, please, ignore my gender, but I doubted it would have a dampening effect. If anything, it would have made things even more awkward. There were other women in the Army, mostly secretarial and nursing, but presumably none were quite as jumped-up as me.

‘Ahem, as I was saying, it’s going to be a bit of work this time to beat the Boche back into his lair. I don’t like speaking ill of our gentlemen in Westminster, but it has to be said, they have miscalculated. Now, that’s between you and me. It’s not to leave this room. I hope we’re clear on that.’

His eyes sought mine. I nodded slightly in an attempt to stop him drawing even more attention to me. He coughed again. ‘Many of us who were in the la

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...