- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

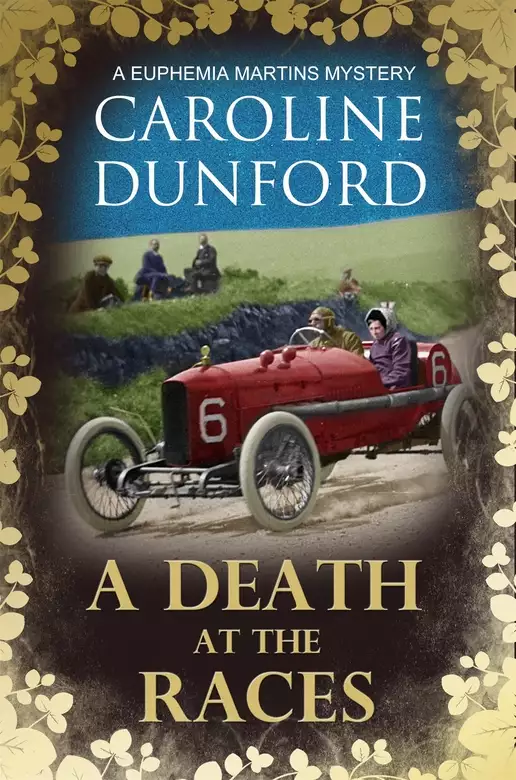

'A perilous predicament for the ever-resourceful Euphemia. Highly entertaining.' - Penny Kline, author of The Sister's Secret 'Euphemia is charming and witty and completely adorable. Loved it.' - Colette McCormick, author of Ribbons in Her Hair It is early 1914, the world is on the brink of war and newly-weds Bertram and Euphemia Stapleford have just returned from their honeymoon. But Euphemia's duty lies with her King and country and she is ordered to accompany spymaster Fitzroy as his navigator in an unofficial car rally across Europe. Their task is to collect top-secret information at a dead drop en route from Hamburg to Monaco. Masquerading as Fitzroy's younger brother, Euphemia endures the most terrifying journey of her life. Before the race has even begun Fitzroy's life is put in danger and further violent attempts to sabotage their mission soon follow. When British double agent Otto begs them to help prevent the assassination of one of the Kaiser's relatives, they don't know who to trust. For it is impossible to tell who is actively hostile, as opposed to merely competitive, in a race in which so many lives are at stake...

Release date: March 19, 2020

Publisher: Accent Press

Print pages: 243

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Death at the Races

Caroline Dunford

I closed Richenda’s door quietly behind me. Hans, her husband, stood in the hall waiting. His handsome face was marred by creases across his forehead. ‘How is she?’

‘She’s sleeping now. She seems content.’

‘Not agitated?’

‘Not at all,’ I said. ‘I think she was quite pleased to see me. She asked me about my honeymoon.’

Hans Muller exhaled a long, slow breath. ‘That’s good. That’s good.’ His expression relaxed, but even by the shaded electric light of the hall, I could see his face was considerably more aged than when I had last seen him, only some weeks previously. His gaze was focused beyond me, into the distance. I moved slightly to remind him of my presence. His attention snapped back to me.

‘She has had some issues with her memory. The doctor says she has a long journey ahead of her. We will not know where it is to end,’ he paused and shrugged, ‘until it ends.’

I took a step towards him and laid a hand gently on his forearm. ‘I am so very sorry, Hans. I wish I could have done more.’

He placed his hand over mine and shook his head. ‘No. No. You mustn’t feel like that. Bertram says without you she would have died, and you also saved our children.’

‘Hardly that. It was Bertram’s actions that saved the day. As for the children, I only told Fitzroy they were in danger.’

Hans looked puzzled for a moment. ‘Fitzroy. Oh yes, that funny chap that had gone along with you as a chaperone. Do you still see him? I’d like to thank him myself.’

I smothered a smile at the thought of Fitzroy ever being a chaperone. ‘No, I haven’t seen him since, and I don’t expect to for quite some time.’ I felt relief merely being able to say this truthfully.

‘Oh well,’ said Hans. ‘I expect I’ll run into him. Especially as he’s a friend of your mother.’ I didn’t correct my brother-in-law. He had no way of knowing that Fitzroy was a member of the British Intelligence Service and that, until recently, both my newly minted husband, Bertram Stapleford, and I had been assets of the Crown. This had changed of late, but I was in no hurry to remember that.

I drew my hand away gently. There had been a time when Hans and I were . . . closer . . . than we are now. I also knew he was not exactly the stand-up gentleman he appeared to be, and I, being newly married and freshly schooled in the ways of men and women, did not want to give him the slightest encouragement. I had no doubt he loved Richenda in his own way, but I also felt reasonably certain he would have already sought out a mistress, with Richenda so ill and unable to . . .

‘Let us go down and rescue the children from Bertram,’ I said quickly.

‘It’s more likely to be the other way around,’ said Hans with the shadow of a smile.

We found Bertram in a large sunny room at the back, sitting on the floor, besieged by Hans and Richenda’s twins, who were somewhere between one and two years old. I had lost count in all the recent mayhem. A small spotted dog with long floppy ears and a clearly mixed background had joined them. It was currently licking my husband’s face and he was laughing. Of the nanny and the Mullers’ older daughter, Amy, there was no sign.

‘Good heavens,’ said Hans, sweeping in and picking up the puppy. ‘I do hope Spot has behaved himself. He is not yet allowed much in the house.’ I saw his gaze sweep across the fine Persian rug that covered the area.

‘He’s a great little chap,’ said Bertram. ‘Normally don’t go for anything less than a gundog myself, but that one’s got a lot of spunk for his size.’

Hans held the dog slightly away from his jacket, which was, as usual, of the finest cloth and superbly tailored. ‘Be that as it may, he should not be in the house at present in case he manages to get upstairs and disturb . . . I see Amy’s hand in this. Where is my daughter?’

‘Oh, she and Nanny had to do something or another,’ said Bertram airily.

‘Hmm,’ said Hans. ‘If you will excuse me a moment.’ He walked out, frowning once more.

I held my hand out to Bertram, who took it gratefully and rose to his feet. It’s true that the many fine breakfasts we had consumed while on our honeymoon had affected his figure slightly, but my husband is not an unfit man. Rather his health, ever since his episode of rheumatic fever as a child, has been compromised. His heart is delicate.

‘That was rather splendid,’ he said, looking down at the two cherubs who went back to playing with their wooden blocks. ‘Do you think we will have children soon, Euphemia? I think I’d like two, or three, if that is all right with you. The twins have invented their own language that only they speak. Clever little things.’ He smiled fondly.

I was about to scoff, but as I observed the children, they did seem to be communicating as they built their little towers. ‘Possibly,’ I said. ‘I do not know that much about children, but these two are very pleasant.’

‘We are going to have some, aren’t we?’ said Bertram, regarding me with wide brown eyes that would put the sweetest puppy to shame.

‘Naturally,’ I said. ‘It’s the normal way of things. But I do think I should remind you that we have little choice over what kind of child or children we may have. They may not be as mild-mannered as these two.’

He met my eyes. ‘You’ve guessed, haven’t you?’

‘Amy was taken away because she had another tantrum?’

Bertram nodded.

‘She found adjusting to the twins difficult enough, and now with her mother unavailable . . . I do feel for her. I fear that Hans, without Richenda’s influence, will be a stern father.’

‘Well, she isn’t his, is she?’ said Bertram. ‘He’s bound to feel differently about her. Anyway, never mind that, how is the old girl.’

I shushed him as I heard Hans’ footsteps in the hallway. Bertram had opened his mouth to ask me why I was shushing him, so I stepped on his foot. I felt resistance beneath my foot.

‘Ah,’ he said and smiled at me in a misty, soppy sort of way.

‘Still stepping on your foot to make you behave, is she, Bertie?’ asked Hans.

‘It’s become quite our thing,’ said Bertram. He waggled one foot in the air. ‘She even bought me these bespoke steel toe-capped shoes as a wedding present. They’re quite smart, aren’t they?’

Hans raised an eyebrow. ‘Indeed.’

‘We can’t afford to buy fancy fitted shoes all the time, you know,’ said Bertram, a slight edge to his voice.

‘It has been a lovely visit,’ I interjected, ‘but if we are to have any chance of reaching home while it is still light, we must leave at once.’

Hans glanced out of the window. ‘I think we have already missed that mark. The winter day is short here, and even shorter as you go further north. Will you not stay another night?’

‘Thank you, but no. We are all packed, and Stone will have put our things in the car. We have had a lovely time, both here and on our travels, but it really is time for us to be going home.’

‘Starting our new life together,’ said Bertram, taking my hand and squeezing it.

‘If you insist,’ said Hans, smiling. He walked with us to the door. ‘Enjoy your time together,’ he called as we climbed into the car. ‘You never know what’s around the corner.’

We both smiled awkwardly, and Bertram drove away.

‘Gods, that was painful,’ said Bertram as we cleared the drive. ‘I mean the children, the dog, the dinners were fine. But Hans lurched between being a perfect host and a depressing creature of doom. You were all right. You didn’t have to sit with him after dinner, drinking port.’

‘Neither did you,’

‘Yes, well. He does keep a particularly fine cellar.’

I leaned my head carefully on Bertram’s shoulder. ‘He’s had a bit of a time,’ I said.

‘Haven’t we all?’ said Bertram. ‘Is my sister on the mend? Or has she turned into some sort of gibbering idiot?’

I punched him lightly on the arm. ‘Honestly, she didn’t want you to see, what with the bandages and everything. She’s fine. Or will be.’

‘She took an enormous blow to the head. And you know better than most that sanity is not my family’s strongest trait.’

‘She’s quieter. More thoughtful. Her speech is slow and a little slurred at times. She has difficulty using one of her arms and the lid on her right eye droops slightly. But you’d only notice that if you looked closely.’

Bertram made a grunting noise. ‘Sounds like a basket case to me.’

‘Bertram! She is your sister, and while she might have been a little unkind to you when you were young, since she married Hans she has become a much better person.’

‘That’s largely due to you,’ said my husband. ‘Besides, she wasn’t a little unkind, she was a hell-cat, cruel as a witch, and Richard’s eager little helper in whatever nastiness he conjured up.’

I didn’t respond. I knew Bertram cared for Richenda, and if he wanted to distance himself from his feelings for her until we knew she would survive, I could understand that.

‘Goodness only knows how she landed Hans,’ he finished. ‘Despite being a bit moody at times, he’s an all right chap. Must be the German half of him that gets the low moods.’

‘I think it is best if we don’t comment on his nationality to others,’ I said.

‘I know,’ said Bertram. ‘War is coming, so says everyone. Why they can’t all sit down at a table and sort it out, I’ll never know. I mean, if my family could manage to dine together when necessary, surely old Vicky’s lot can?’

‘Bertram! That is no way to talk of our late Queen and her relatives.’

‘I mean . . . Kaiser Wilhelm is her grandson or something, isn’t he? Our King’s cousin, or some such?’

‘I believe it to be somewhat bigger than that,’ I said.

‘Well, never mind. We don’t have to bothered by all that anymore, do we?’ said Bertram. ‘You’re married to me now and we will live happily together in the Fens for the rest of our days.’

‘Of course,’ I said, laying my head on his shoulder once more. I had my doubts about the Fens, but other than that, I was content. In time, I intended to persuade Bertram to spend some of the money I had inherited from my grandfather on a place in London, so we could split our time between there and Norfolk. I wasn’t convinced that a cold, damp Norfolk winter would be good for Bertram’s health, or my own sanity.

‘At least that man is out of our lives,’ said my husband with great finality. ‘I cannot tell you how good that makes me feel.’

He shifted his shoulder under me. ‘Bit uncomfortable that. Must be all those brains in your head. Settle back and try and get some sleep. I won’t be driving fast, so it’ll be some time before we’re home. Hopefully those rugs and that hot brick will keep you warm enough.’

‘If you’re sure,’ I said, snuggling down and making a pad of a second, smaller rug to rest my head against the door. ‘Not driving fast, though . . . should I be worried about you?’

‘My wife’s in the car,’ said Bertram. ‘I need to get her home safely.’

‘Wife’s an awfully nice word,’ I said.

‘It is, isn’t it? Almost as good as husband.’

It took me a little while to fall asleep. I turned my face away from Bertram so he wouldn’t fret. Around us the dusk descended softly. The sky dissolved in a gentle greyness with wisps of white creeping in and out of the tree-lined road. Eerie, but pretty, I hoped that it didn’t herald a complete fog. The area where White Orchards stood was much prone to mist and if it had already begun down here, I feared that it would be blanketed white out there.

True to his word, Bertram drove, uncharacteristically, with great caution. I didn’t know if Hans’ parting words had struck a chord, or if he was finally paying attention to the weather conditions. Normally, he simply protested that the road remained regardless of weather, and as he was short-sighted anyway, what did it matter? He claimed he drove by instinct. Once we were home, he would have no reason to use to the car to any great extent. This, I was looking forward to, but not much else. I was familiar with the house, having worked there for a short time as a housekeeper. Although in better repair than when Bertram bought it, the building still festered with issues brought on by careless contractors and agents. No sooner was one part fixed than another demanded urgent attention. The total collapse of the kitchen ceiling still remained the most dramatic.

But it wasn’t simply the state of the house. My trust fund could stand that. It was the isolation of the place that I feared. My old friend Merry would be there, married to Bertram’s chauffeur, Merrit, and expecting her first child. She lived in a small cottage on the estate. I had no idea how she felt about associating with the lady of the house. I would need to tread carefully. But apart from the other tenants, there was no society nearby. I didn’t need the rush of daily entertainment, but the occasional family with whom we could share dinner, or even the odd exhibition to view, would have alleviated my doubts. Bertram would be happy with three cooked meals a day, a companion to play chess with, and a weekly delivery of new books from London. He needed little else. I suspected this would not be enough for me. I loved him dearly, but I had discovered of late I was not made for a quiet life. My hope was that, now being an Agent of the Crown, I could have periods of adventure interspersed with the restful home life that Bertram longed for. Of course, I still had to tell him about my arrangement. Technically, as my husband, he could forbid my actions. Not that he would dare, but the last thing I wanted was to put him in conflict with my spymaster who, despite his charm, was deceptively ruthless.

Bertram hummed quietly to himself as he drove. I did a good job in mimicking sleep, but the reality of it evaded me. The temperature outside fell, as did that of the hot brick at my feet. If I fell asleep now, I thought, I might well catch a chill.

I felt the car slow and Bertram ceased all sounds. I peered out as much as I could without moving my head. There, in the headlights, stood a roe deer and behind her a fawn. She had stopped in front of the car to allow the little one to cross. Not the greatest of plans, but a motherly one, nonetheless. Beside me I heard Bertram inhale softly. I risked a glance and saw him looking at the animals with reverence.

The headlights picked out the soft brown hair on the doe’s back, and her graceful, dignified face, with one ear twitching. Behind her the fawn trotted quickly across the road without even glancing in our direction. Perhaps, I thought, finally sliding towards sleep, Bertram and I could share a new interest in studying the wildlife of the Fens.

I awoke to the sound of my teeth chattering in my head. I felt cold through to my bones. The engine noise had disappeared. I opened my eyes and sat up, fearing we had broken down. My thoughts were still untangling from a dream in which Bertram and I had been driven to the edge of a quagmire by giant swans with razor-sharp beaks. We clung to each other as we descended into the murky depths. I don’t think I had ever been more pleased to see the shadow of White Orchards rising up before me.

Bertram came around to my side of the car and opened the door. ‘Careful, you’ll be stiff with cold.’

‘I’m fine,’ I said, before discovering my legs no longer worked and, still tangled in a car rug, I fell straight in his arms. He caught and embraced me.

‘I’m sorry, Euphemia. I should have got them to load more rugs. I didn’t realise it would take so long to get back. I had to drive ever so slowly. The roads are swathed in fog.’

‘We’re here now,’ I said. ‘Let’s go and sit in front a fire and thaw out.’ At least that is what I meant to say, but my teeth were chattering too hard to speak clearly. Fortunately, Bertram was of the same mind. He helped me up the stairs to the entrance, where his new butler stood with the door wide open. A warming blast of heat washed over me.

‘Welcome home, sir, madam.’

‘Giles, I take it you have some fires burning?’ said Bertram.

‘In the main hall, the smaller saloon, the master bedroom, the library, and of course the kitchen, sir. I did not think that tonight was a night to worry over fuel.’

‘Indeed not,’ said Bertram. ‘Once this place gets cold, it needs the fires of Hell itself to warm up the stone. Please ensure the fires in the servants’ hall and the upper attics are also lit. We all need to keep warm. Did I imagine things or was there another car in the . . .?’

I slipped my hand off Bertram’s arm and walked over to the hall fire. I still had a car blanket around me and I stood warming myself. The firelight danced across the panelled wooden walls, and the ebony table with its Tiffany lamp. The grandmother clock ticked faintly in a niche by an inset bookshelf. Large mirrors reflected the gentle glow from the hearth around the hall, eliminating the shadows and giving the place a most homely look. How could I ever have doubted that White Orchards would please me? I felt profoundly relieved to be home.

Bertram finally came in and Giles closed the big oak door. I remembered an old saying about all being safely gathered in for the night and gave a contented sigh. I looked up at Bertram to give my best welcoming smile. He knew full well I was not the greatest fan of White Orchards in general. However, the smile faded from my lips when I saw the frown on his face.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘It appears we have a visitor,’ said my new husband.

‘Not tonight,’ I said. ‘Giles should have refused them.’

‘Apparently he tried, but to no avail.’ Bertram’s upper lip was looking uncommonly stiff.

‘Who on Earth is it?’

‘He refused to give his name, but I rather suspect . . .’

As if waiting for his cue, our visitor erupted out of the library door. ‘It’s rather late, you know,’ he said. ‘Poor Giles was beginning to worry. You could have telephoned him. You do know I had a telephone put in, don’t you? It’s my wedding present to you. I’m sure you’ll both find it very useful, living out in the middle of nowhere. May I kiss the bride?’

And with that, he darted towards me and, before I could step back, put a hand on each shoulder and placed a firm kiss on each cheek.

‘Fitzroy,’ I said wearily.

‘Fitzroy!’ cried Bertram. ‘What the devil do you mean by showing up here. Tonight, of all nights?’

The spy smiled charmingly and tilted his head on one side. ‘I don’t suppose you would accept I merely happened to be passing?’

‘On a filthy night like this, in the middle of nowhere?’ said Bertram. By now I could see he had begun to quiver with rage.

‘I wanted to give you my best wishes for your future happiness.’

‘Fitzroy . . .’ said Bertram in a low voice and through gritted teeth.

‘Oh, very well,’ said Fitzroy, shrugging. ‘I needed to speak to Euphemia and as it happened, I was nearby. Can’t tell you where or why.’ He smiled again, perfectly at ease invading our home late in the night.

Bertram turned to me. ‘I thought I had made it perfectly clear that we were to have no more dealings with this man?’

‘Heavens, Euphemia,’ said Fitzroy. ‘You’re barely married a moment and he’s gone all dictatorial.’

Bertram flushed slightly red. ‘I mean, I thought we had agreed this chapter of our lives had closed?’

Fitzroy looked from him to me, clearly enjoying the situation. ‘I take it you haven’t told him yet?’

‘Told me what?’ said Bertram, having been flushed, he suddenly paled. ‘It was a real vicar that married us, wasn’t it? It wasn’t one of his ploys?’

‘Honestly, Bertram,’ I said, taking the higher ground while I could, ‘we have been living as man and wife for over a week. Do you think I would . . .’

Bertram went back to being flushed. ‘No, no, no, of course not,’ he said. ‘It’s just with that dastardly fellow, one never knows where one stands.’

‘The dastardly fellow is still here,’ said Fitzroy. We both ignored him.

‘You’re quite correct in saying that I wanted to close this chapter of my life upon our marriage . . .’ I said.

Fitzroy staggered dramatically as if shot, one hand pressed to his chest. We both continued to ignore him.

‘However, that was before I was charged with murder.’

‘Yes?’ said Bertram. It may have been a trick of the firelight, but the loving look in his eyes appeared slightly diminished. His tone was certainly wary.

I looked over at Fitzroy. ‘I take it I can tell him now?’

‘As long as Giles isn’t lurking in the shadows,’ said the spy.

‘He wouldn’t let me tell you until we were married,’ I said in a rush. ‘I wanted to, but he made me promise, and I couldn’t . . .’

Bertram held up his hand. ‘This man has some hold over you?’ he asked. ‘You give your obedience to him over your own husband?’

‘Oh no,’ said Fitzroy. ‘She’s never been obedient with me. Reluctantly compliant? Aggressively acquiescent? Contemptuous? Which is best applied, Euphemia?’

‘If you could stop enjoying yourself for a minute, and let me explain,’ I snapped. ‘Go back into the library. I wish to speak to my husband alone.’

Fitzroy gave a mock bow. Then he threw me a wink behind Bertram’s back that I interpreted as a sign he would be listening in.

‘So?’ said Bertram as the door closed behind the spy.

I sighed. ‘So, when I was arrested for murder, Fitzroy offered me two ways out of the mess. One was to flee abroad—’

‘What!’ exploded Bertram.

‘Oh, not like that,’ I said. ‘He doesn’t think of me in any romantic way. I’m useful to him, that’s all.’

‘How?’

‘As an asset,’ I said, ‘nothing more. Or, it was nothing more.’

‘Euphemia, if you don’t stop prevaricating and spit it out, I swear, I will take that umbrella over there and go into the library and thrash that man.’

I could almost hear the eavesdropper thinking, you can try. ‘I joined the intelligence service,’ I said, ‘as an Agent of the Crown. I’m only allowed to tell one person, and Fitzroy said as I kept almost getting married, I shouldn’t tell you until after we were. I agreed. I’d rather not have told you at all.’

‘Is that all?’ said Bertram.

‘What do you mean?’

‘You’re a spy now? It always seemed to me you were doing the lion’s share of the work whenever we were involved with him. I can’t see how it would be different.’

‘I took an oath,’ I said, ‘to protect King and. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...