- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

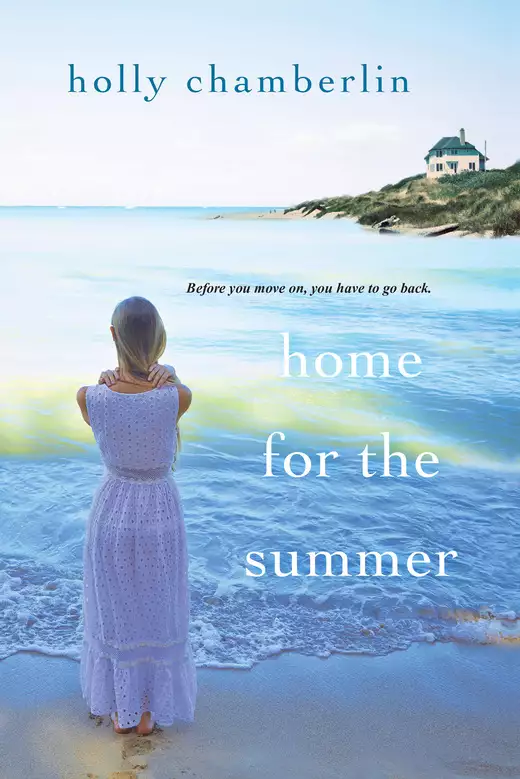

In bestselling author Holly Chamberlin’s poignant new novel, a mother and daughter escape to a beautiful coastal town in Maine to find healing in the wake of heartbreaking loss. The journey to Yorktide, Maine, was always a happy one for Frieda and Aaron Braithwaite and their two daughters. Frieda loves her mother’s old farmhouse, and the girls have grown closer there, sharing a bedroom and spinning stories into the night. But that was before—when tragedy was something that happened to other families. Since the car crash that claimed the lives of her husband, and their younger daughter, Frieda has struggled emotionally and financially. Bella, now seventeen, is withdrawn and wary, and Frieda fears losing her too. At her mother’s urging, Frieda decides to return to Yorktide with Bella for the summer. Bella gets a job in a local shop, and little by little edges her way back into the world. But it’s the unexpected connections they make—with a former schoolmate, a troubled teenage girl, and Frieda’s estranged father—that will spur them to find healing amid bittersweet memories, and discover if their bond is strong enough to guide them back to hope once more. Praise for the novels of Holly Chamberlin “Chamberlin’s latest is a great summer read but with substance. It will find a wide audience in its exploration of sisterhood, family, and loss.” – Library Journal on Summer With My Sisters “Nostalgia over real-life friendships lost and regained pulls readers into the story.” — USA Today on Summer Friends

Release date: June 27, 2017

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 405

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Home for the Summer

Holly Chamberlin

And for the first time ever Frieda and Bella would be staying with Ruby for the entire summer. It was imperative that they did because just before the one-year anniversary of the car accident that had killed Aaron and Ariel, Bella had suffered a serious setback. Every advance she had made toward happiness had stalled. She suddenly refused to see her grief counselor. She suddenly stopped confiding in her mother. Her interest in the world around her had waned alarmingly. Frieda was at her wit’s end. Ruby was not. She had summoned her family home.

“We can’t let this situation go on,” Ruby had told her daughter. “Bella is slipping away from us and we’re allowing it. Maybe together we can prevent a disaster. We have to believe that we can.”

Ruby shifted and her right leg protested. “Stupid leg,” she muttered. Well, it wasn’t the leg that was stupid; in fact, there was nothing stupid about the incident that had resulted in her right tibia being smashed to bits a little over a year ago. It had happened very early one morning. A fifteen-year-old patient had suddenly gone wild, flying from his bed, tearing out his IV drip and monitor attachments, and thrashing angrily at whoever got in his path. Ruby had joined two other nurses trying to subdue the boy before he could hurt himself, but he managed to break free. Ruby and her colleagues pursued him and Ruby managed to catch the boy just as he tore open a door at the end of the hall. And that’s when it happened. The boy, his eyes wide with fear, roughly pushed her away and she had fallen through the doorway and down that never-ending staircase.

It wasn’t the patient’s fault. A bad reaction to one of the medications he had been given had caused the brief but terrifying event. He had little recollection of the episode afterward and had been released a few days later. Ruby hadn’t been so lucky. Two surgeries; three months of putting absolutely no weight on the leg, which meant getting around in a wheelchair and with generous and uncomplaining assistance from her beau, George Hastings; a slow graduation to a walker and then crutches; and, finally, a cane. Now, sixteen months later, Ruby walked unaided but with a slight limp that she suspected would be hers for life.

A limp she could live with. What Ruby sometimes felt she couldn’t live with was the unreasonable but no less painful guilt she felt about having missed that fateful vacation in Jamaica the previous April. If she hadn’t intervened with that disturbed patient she wouldn’t have broken her leg. If she hadn’t broken her leg she wouldn’t have had to stay home while Frieda, Aaron and the girls went off to celebrate Bella’s sixteenth birthday in style. If she had been in Jamaica with them maybe she could have . . . Could have what, Ruby thought for the thousandth, the millionth time. Could have prevented the car accident that had taken Aaron’s and her sweet Ariel’s lives?

“The little cricket on the hearth has stopped chirping,” Ruby whispered aloud, “and the sweet sunshiny presence has vanished, leaving silence and shadow.” It was a paraphrase of a few lines from Little Women, one of her favorite books. Like Beth, Ariel had been one of those special people whose enormous influence was only fully realized in her absence.

And indeed Ariel’s favorite place to be in her grandmother’s home had been curled up in one of the armchairs in front of the living room fireplace, a big stone structure with a wide mantel and deep hearth. The house surrounding this magnificent fireplace had been built in three stages, starting in 1834. From what scant records there were at the town hall, Ruby had managed to estimate that around 1872 an addition had been added and then, around thirty years later, a new kitchen and, for the first time, a bathroom. There had been a barn on the property at one point but that was long gone; in the mid-1980s the then owners had replaced it with a two-car garage.

After so many years of living in cramped spaces, whether it was an apartment over a store in town or a cottage behind a landlord’s spacious three-story home, Ruby gloried in wandering the many rooms of the farmhouse—nine in all if you counted the mudroom off the kitchen and Ruby did. She gloried in knowing that it all belonged to her and her alone. If there was little cash to leave to her family at the end of what would hopefully be a long life (she was only sixty-four and gunning for another twenty years) then at least there was this structure, solid and tangible, to gift to the future.

There were hooked or braided rugs in every room, many made locally. The aforementioned stone fireplace kept the house heated during the autumn and winter months. The kitchen was painted a cheery yellow and there were lacy white curtains on the window over the sink. There were four bedrooms on the second floor. Ruby’s bedroom was decorated in shades of soothing blues and greens. The second bedroom was a bit smaller; the center of attention there was a beautiful white coverlet with matching white curtains. The third bedroom was painted a rosy pink. In the smallest bedroom, the one with a pullout couch, an enormous wreath of pinecones hung over the bed, a gift from the grateful mother of one of Ruby’s patients.

Ruby had found most of the furniture at antique shops and yard sales. Phil Morse, her best and oldest friend and a master of home decoration, had advised her in the art of haggling so that even after the purchase of major items like the pine table for the kitchen Ruby’s budget hadn’t suffered unduly. Even though there was nothing the house really needed in the way of essentials, Ruby still enjoyed cruising flea markets and antique malls for the odd “must have” item, like the bright orange Fiesta Ware vase she used as a container for wild flowers and the milk glass salt and pepper shakers just like the ones Ruby’s mother had owned.

In short, Ruby felt she couldn’t be happier or more content living where she did, in this lovely house in Yorktide, Maine. Well, one thing might make her happier she thought, looking again at her watch. It was ten minutes past two. She hoped there hadn’t been an accident—Stop it, Ruby told herself. Don’t let that happen. Don’t let fear take over, not after all you’ve been through. Not, she thought, when there were so many challenges to face, like the matter of George, that wonderful man who had presented her with a dilemma she wasn’t sure she had the strength to solve.

Just then Ruby spied her daughter’s car as it turned onto Kinders Lane and breathed a sigh of relief. She hadn’t been seriously worried; she hadn’t really thought there had been an accident. Still, the sight of Frieda’s serviceable Subaru pulling into the driveway was very, very welcome.

There was a lot riding on this summer, Ruby thought, hurrying to the front door, most important, her granddaughter Bella’s future. And that meant the future of the entire family. What was left of it.

“Bella, aren’t you hungry?” Frieda asked. Her daughter’s voracious appetite was well known; even in the weeks after the accident she had shown interest in eating while Frieda had barely been able to tolerate the cups of strong, hot tea people seemed to keep forcing on her. But since the anniversary of Aaron’s and Ariel’s deaths in April, Bella’s progress toward a place of peace seemed to have come to a halt. No, Frieda thought. What had happened was more like a reversal, not simply a halt.

“Not really,” Bella said, pushing another bit of her dinner around the plate.

“Eat something,” Ruby said. “No wasting away allowed in my house. Besides, I’ll take it as an insult to my cooking if you don’t eat.”

Bella gave a ghost of a smile and took a bite of the pasta and calamari Frieda’s mother had prepared.

“So,” Ruby announced suddenly. “Now is as good a time as any to discuss house rules.”

Frieda was surprised. “You’ve never set house rules before,” she said. “I mean, besides the obvious like ‘don’t forget to turn off the burners on the stove when you’re done using them.’”

“True,” her mother told her. “But you’ve never spent more than two weeks at a time under this roof. You’ve always been more my guests than my roomies. This summer it’s different. If the three of us are going to cohabitate peacefully for the next few months we each need to help out around the house. We’ll take turns making dinner as well as cleaning up after it, and that means not only loading the dishwasher and washing the pots and pans and knives but also wiping the table and sweeping the floor. Oh, and scrubbing the cutting board. We can’t have one of us coming down with salmonella poisoning.”

Bella, who had never shown the least bit of interest in housekeeping, didn’t protest her grandmother’s directions, as Frieda might have expected her to. But things were different now. Bella was different. They all were.

“And Frieda,” Ruby went on, “you can share the grocery shopping with me and running whatever odd errand needs to be run. George has been handling most of the yard work since my accident—stupid leg—but he might need assistance at some point. He’s got a home of his own, after all.”

“Sure, Mom,” Frieda said. “Whatever I can do to help.” After all, she thought, her mother had offered a lifeline to her daughter and granddaughter this summer. Without Ruby’s assistance Frieda wasn’t sure she could help Bella in the way she needed to be helped—whatever way that was. “Whatever either of us can do,” she added.

Her mother nodded. “Good. Bella, you’ll need to keep your room clean and tidy, which means changing your sheets once a week and vacuuming the rug and dusting the furniture. And we can each do our own laundry so there won’t be any mix-ups resulting in shrunken clothes, et cetera. I’m partial to my cotton sweaters staying in one piece.”

Bella still didn’t protest these additional chores, but Frieda thought her expression betrayed the slightest bit of rebellion. If that was true, it was a good thing. Bella once again showing some spirit.

“And as for Bella’s paying job—” Ruby began.

“A job?” Bella’s voice held an undeniable note of annoyance. “Why do I have to get a job?”

At last, Frieda thought gratefully. A bit of resistance! “Mom,” Frieda said, “I’m not sure that’s really necessary. Bella needs time to—”

“It will be good for her to get out of the house and interact with people,” Ruby said firmly. Then she turned to Bella. “I’ve arranged for you to work at Phil’s shop twenty hours a week, more if you want the hours. He’ll set your schedule.”

Bella laid her fork on the table. “But I know nothing about curtains and rugs and stuff like that,” she said.

“You’ll learn. Phil’s a good teacher and he’s more patient than most people.”

Frieda watched her daughter’s face closely as the brief spirit of protest faded.

“All right,” Bella said quietly. “May I be excused?”

“Yes,” Frieda said before her mother could usurp her authority.

Bella got up from the table and a moment later Frieda heard her climbing the stairs to her room. She had barely touched her meal.

“Mom,” Frieda said, “don’t you think you’re being too tough on Bella?”

“No, I don’t. Don’t bite my head off, Frieda, but I think you might be indulging Bella’s grief by not urging her into more activity. Have you encouraged her to start studying for her driver’s license again?”

“No. Back in March she said she was thinking about it, but then she told me she was still too scared to get behind the wheel. She said that if her own father—”

“I know what she said,” Ruby interrupted. “But she’s going to have to get past the fear sometime if she’s to be independent.”

“She’s doing all right on her bike,” Frieda protested, but she knew her mother was right. The crushing fear of driving that had come over Bella since the accident had to be conquered. At least Bella found riding in a car tolerable. That was something, wasn’t it?

“And when she wants to go somewhere too far away for her to cycle there, what then? Is she going to rely on you forever? Are you going to allow that?”

“Mom,” Frieda protested. “Don’t be dramatic. It’s only been a little over a year.”

“And what about Colleen, her grief counselor?” Frieda’s mother pressed on. “They were doing good work together from what I could see. Have you told Bella she needs to go back to seeing Colleen?”

“I’ve encouraged her to go back, yes.”

“But have you forced the issue?”

“No,” Frieda admitted.

“You can, you know. You’re her mother; you’re allowed to tell her what to do.” Ruby sighed. “I know you don’t want to hurt her, but I’m afraid you might not be doing what’s ultimately in her best interest by, well, by letting her off the hook. It’s not okay that she not engage.”

There was truth in what Ruby said; Frieda couldn’t deny that. Still . . . “It’s just that I’m so afraid of pushing her too hard or of alienating her to the extent that she’ll never come back to me. To us.”

“I know.” Her mother reached across the table and took her hand. “I do. And I’m sorry if I came across as a bit heavy-handed just now. I’m not opposed to coddling. We all need to be protected from the misery of life at times. But only at times, or else we become quivering masses of uselessness.”

Frieda managed a smile. “Charlie, my grief counselor, says that avoidance has its place in healing, but it’s a very small place. It’s sometimes hard to remember that.”

“Smart man.” Ruby released Frieda’s hand and sat back.

Frieda sighed and rubbed her forehead. “Bella and I were a comfort to each other after the accident, Mom. What happened to make it all go wrong? I’m so afraid Bella’s setback isn’t only about the feelings the anniversary of the accident brought on. I’m so afraid that I relied too heavily on her this past year and didn’t give her enough of the care she needed. Maybe she just can’t bear the burden of my grief any longer. And if that’s the case, how can I change things? What if I’ve caused irreparable damage to my child by being so selfish?”

Ruby shook her head. “No. I saw how well Bella was doing. She was making real progress. Whatever happened to send Bella slinking back into the darkness had nothing to do with you; I’m sure of it.”

Frieda smiled ruefully. “How can you be?”

“All right then, I’m as sure of your innocence as I can be.”

“Thanks,” Frieda said. “I guess. By the way, where’s George? I thought he’d be here.”

“I asked him not to join us for dinner,” her mother told her. “I thought it would be better for the three of us to be alone this first night.”

“Was he okay with that?”

Her mother smiled. “George is okay with everything. Sometimes I think he’s too good for me.”

“Mom, you completely deserve someone who treats you with the respect and love George shows you. Believe it.”

Her mother didn’t reply but pushed back her chair and stood. “I’ll clear away the dishes tonight. You had a long drive. Why don’t you just relax this evening?”

“Thanks, Mom,” Frieda said gratefully. “I am tired. And Mom? Thanks for asking us to spend the summer with you. I know our being here might cause some disruption to your life.”

Ruby smiled. “You’re my family. I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

It was after eleven and Bella had been up since seven that morning, but as tired as she was, she just couldn’t sleep. At the moment she was sitting on the edge of her bed, lights off, staring at the closed door of the room with the rosy pink walls. She knew this room so well. The whole house, really. It was welcoming, almost like a friend.

Unlike the new house back in Warden where she and her mother had lived since the previous August. There was a sense of anonymity about the place; it almost felt as if they were living in a hotel room, that the house wasn’t really theirs and might never be. Her mother had sold some of their furniture; other pieces were in storage. Only a few photos of Bella’s father and sister were on display in the living room. In Bella’s room there were no photos at all. And nowhere were there signs of the Braithwaites as they had been: no scuff marks from the times Bella would forget to take off her soccer cleats before going into the house; no horizontal pencil marks on the wall next to the fridge where her father had charted Bella’s and Ariel’s growth; no bit of kitchen counter stained yellow, evidence of the time her mother had spilled ajar of curry sauce; no strands of Ariel’s long red hair in the brush on the bathroom sink. The odd thing was that Bella found some comfort in the anonymity of the new house. At least, she found it more tolerable than she had found living in their old house, where the memories were loud and painful and constant.

It was odd, Bella thought, but here, at another house so full of the past, she was okay with staying in the room she had once shared with Ariel. She could easily have moved into the smallest bedroom. There was a couch there that folded out to a bed and a closet where she could hang her clothes when she remembered to hang them.

Bella glanced over her shoulder at the empty bed by the window and then turned back to face the door. Maybe she could ask her grandmother if Phil or George could move the bed out of the room. Or maybe she could just do it herself. There was a screwdriver in the junk drawer in the kitchen. She could take apart the frame and . . . Then what? How was she supposed to get the mattress and box spring down the stairs without disaster?

Whatever. The bed could stay. She would try not to look at it. Maybe she would just pile all of her clothes and stuff on top of it. That might prevent her from seeing in her mind’s eye Ariel’s gorgeous red hair spread out on the pillow, her knees tucked up against her chest, her hands folded under her cheek in her sleep.

Bella sighed. It had been so much fun sharing this room with her sister. Sometimes at night, with the rest of the house asleep, they would sneak out to the Jernigans’ property, on which there was a natural spring. Ariel had liked the sound of the spring bubbling in the dark. Bella remembered her sister telling her how the early Christians often built shrines to saints on sites that had been sacred to the pagans, so that the sites—like natural springs—remained incredible sources of spiritual power and belief through the centuries.

“You really find this interesting?” Bella would ask when Ariel went on about old stuff, which she often did.

“Yeah,” Ariel would say. “It’s fascinating. It’s our history.”

“Whose history?”

“Ours. Human beings.”

Sometimes Bella had wondered how Ariel had put up with her sister being so stupid. But the answer to that question was easy. It was love, pure and simple. The love shared by siblings, which could be far stronger than even the greatest love between friends. On some level Bella had always known that, but it had taken Ariel’s dying to fully open her eyes to the depth of the bond they had shared. You don’t know what you have till it’s gone. Whoever had first said that was so very right. Bella had lost not only a sister. She had lost the other half of herself.

Bella got up from her bed and went to the window. There was little to see by the one small light near the door to the mudroom and the sky was moonless. She leaned her head against the cool glass, closed her eyes, and remembered those final days with her sister. Even though Ariel hadn’t gone with Bella to the resort’s disco or to play beach volleyball—Ariel hadn’t liked dance music and she was hopelessly bad at sports—they had had such a good time together. One night they tried curried goat. “Could use more Scotch bonnets,” Ariel calmly noted as Bella wiped sweat from her face and reached for her water. They went shopping together. They went to a reggae concert one afternoon. They took long walks on the beach during which they talked about all sorts of stuff.

In short, they had been as they always had, the very best of friends. Then, Bella thought for possibly the millionth time, I had to go and ruin everything at the last minute by calling Ariel a dork for wanting to poke around in a dusty old museum. It was only a joke, but words hurt, no matter how innocent the intention behind them. So why had she said it? What was wrong with her?

And worse, even though Ariel hadn’t been there to hear it, Bella had told her mother she would kill her sister if she was the cause of the family having to take a later flight home. It was a horrible thing to have said, even in jest—you would kill someone because they made you miss a television show?—and the words haunted Bella. Since the anniversary of the accident those damning words had never been far from her mind.

Bella turned from the window. Wearily, she lay down on her bed and pulled the fresh cotton sheet over her legs. Her mother seemed to think it would be helpful in some way if they lived with her mother for the summer, but in what way it would be helpful Bella had no idea. What was going to happen or not happen here at her grandmother’s house in Yorktide that could or could not happen back in Warden? Bella turned on her side and tucked her hands under her cheek as Ariel used to do. She guessed that only time would reveal the answer to that question.

The house was profoundly quiet, but through the open window Frieda could hear the mournful hooting of an owl. She hadn’t turned off the light yet. It was comforting somehow to look at the colorful bits of sea glass arranged on the windowsill. It was one of the simple pleasures of being at home with her mother. And some feeling deep down made Frieda believe that if healing and happiness were ever to be found again it would be at the house on Kinders Lane.

Frieda would never forget the housewarming party her mother had given not long after she had settled in. Ruby had been downright jubilant that afternoon, leading tours of the house, bragging about the bargains she had gotten on various bits of furniture, offering endless platters of appetizers to her guests. After all the years of hard work, self-sacrifice, and sometimes frighteningly real financial struggle, Ruby Hitchens had heroically achieved her goal of owning her own home.

And it wasn’t the first time that home was acting as a refuge for family, Frieda thought. Last Christmas without Aaron and Ariel back in Warden had been awful; around every metaphorical corner there was a memory of happy holidays spent as a family of four. And being in the new, much smaller house had added to the sense of loss and desolation.

“Let’s get out of here, Mom,” Bella had said fiercely one afternoon. “I can’t stand it in this place.”

Neither, Frieda had thought, can I. So on Christmas Eve they had packed up the car and made their escape to Yorktide for the remainder of the school break. If the days under Ruby Hitchens’s roof hadn’t been joyful, they had at least offered some degree of peace. And if memories of past Christmases had followed Frieda to Maine, at least they were happy memories.

Unlike other memories that were tinged with regret. Frieda turned from the window and walked over to her bed. How oblivious we are to the potential tragedies just around the corner, she thought as she lay down. How blithely we waste our lives. What haunted Frieda most about that last morning of her husband’s life was the missed opportunity for a last real kiss with the person she loved best in the world. Why had she given Aaron her cheek? He wouldn’t have minded if there was a crumb on her lip. But it was too late now.

There would be no more kisses. There would be no more shared meals. Aaron would never again bring his wife a cup of coffee in bed. Who knew that after the death of a loved one, simple daily activities such as making coffee could cause such confusion and disorientation? That first morning back in Warden after the accident Frieda had found herself staring at the jar of coffee beans and the grinder, momentarily stymied. How to begin? How many ground beans made how many cups of coffee?

It had taken real strength of will to brew that pot of coffee, the first of many reminders that focusing on real-world tasks was a very important part of dealing with death. You might want to retreat to your bed and pull the covers over your head, but you couldn’t, not for long, not when there were decisions to be made, bills to be paid, a child to comfort, and your own health to maintain. All on your own.

Frieda shifted under the cool cotton sheets. She never thought she would be a single parent as her mother had been. Frieda was well aware of all Ruby had sacrificed to raise a child with virtually no financial support from the child’s father. Steve Hitchens. The man who defined ne’er-do-well more precisely than anyone else Frieda had ever known.

Ironically, the situation in which Frieda found herself, raising a child on her own, was all her fault. She had been the one to push for the idea of a big family vacation during spring break. Aaron had been reluctant to take the time off from the architecture firm where he had recently become a junior partner, but he had good-naturedly given in to Frieda’s persuasions. “Sure,” he had said. “Let’s do it.”

And that had been that. Decision made. Lives irrevocably altered.

Frieda yawned and turned out the light on her bedside table. She was so very tired. Though she knew it was a futile gesture, she patted the empty space next to her in the crazy hope that she would find her husband by her side.

“I took one look at Bella this afternoon,” Ruby told George over the phone that evening, “at her sad eyes and wan complexion, and I felt furious all over again with my ex-husband for failing our family. Not once has he been there for us when we needed him, like now, when his daughter and his granddaughter are suffering. Where is he now? Who knows! He’s never even met either of his granddaughters! And it isn’t because Frieda’s withheld the girls from him. It’s his choice to be absent.”

“And his loss in the end,” George reminded her.

Ruby sighed. And yet, she thought, I continue to take Steve’s calls. And I continue to love him somewhere deep down inside. “George,” she said, “thank you for listening.”

“You’re in mourning and grief is hard work. I’m glad I can be here for you. Still, I don’t have to remind you that dredging up old hurts doesn’t accomplish anything of value.”

“I know. All it does is wear me out.”

“Try to get some sleep,” George advised. “I’ll pick you up at eight o’clock tomorrow morning. Your appointment with the eye doctor is at eight thirty, right?”

“Yes. He said it would take about twenty minutes for the pupils to dilate. Bring a book to read.”

George laughed. “I’ll have my iPhone. I’ll keep plenty occupied.”

“You and that iPhone! You’re an addict, George. Good night.”

“Good night, Ruby,” he said. “Sleep tight.”

Ruby changed into her pajamas, brushed out her thick shoulder-length hair, only sparsely threaded with gray, and crawled into bed. She was very lucky to have George Hastings in her life. For years after Steve had left Ruby and their eleven-year-old daughter she had been totally focused on raising Frieda, getting her nursing degree, and building a career. There had been no time for men—at least, that’s what Ruby had told herself. In reality her heart had been so badly broken by Steve’s infidelities and eventual defection that she simply refused to risk having it broken again. Mostly she was fine being on her own and when periods of loneliness arose, like, for example, when Frieda became a teen and began to spend more time with her friends and then when Frieda married and moved to Massachusetts, Ruby had managed to do a very good job of quashing the loneliness with extra shifts at the hospital and a renewed dedication to her beloved book group, The Page Turners.

Then, not long after Ruby had turned sixty, along came George Hastings. They met one afternoon in the hospital cafeteria shortly after George had started working in administration; he had moved from New Hampshire to Yorktide to take care of his ageing widowed father. Being divorced with no children, George was perfectly placed to be Walter’s caregiver. “I’m just returning the favor,” George had explained. “Dad’s been a good father to me and now it’s my turn to be a good son to him.”

What began as a chatty companionship over weak coffee and uninspired sandwiches slowly became something more, a friendship Ruby came to cherish. After about six months, George invited Ruby to dinner. “Someplace other than this cafeteria,” he said. “Someplace where the food doesn’t come wrapped in plastic and the coffee actually has a kick.” Ruby said no. George said, “Why not?” Ruby realized she had no good answer. She liked George. And what was the harm in going to dinner? Everyone had to eat. So she said yes.

To Ruby’s immense surprise, a romantic relations

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...