- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

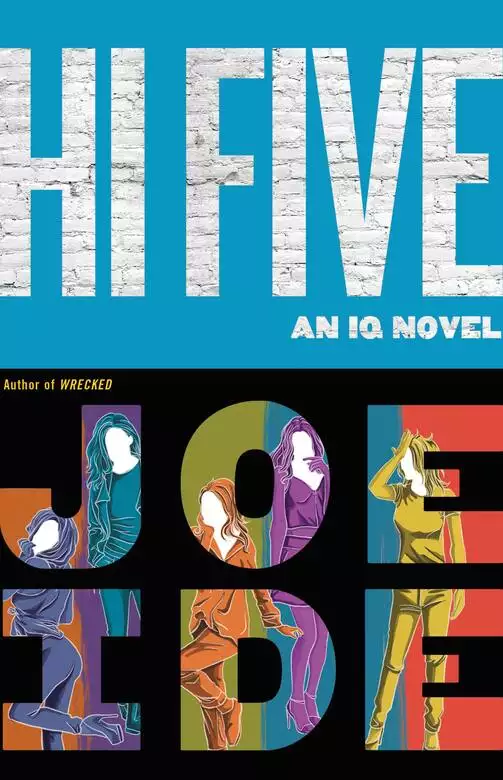

IQ is back—and working a case that involves juggling many more personalities than he expected.

Cristiana is the daughter of the biggest arms dealers on the West Coast, Angus Byrne. She's also the sole witness and number one suspect in the murder of her boyfriend, found dead in her Newport Beach boutique.

Isaiah Quintabe is coerced into taking the case to prove her innocence. If he can't, Angus will harm the brilliant PI's new girlfriend, ending her career.

The catch: Christiana has multiple personalities. Five radically different ones. Among them, a naïve, beautiful shopkeeper, an obnoxious drummer in a rock band, and a wanton seductress.

Isaiah's dilemma: No one personality saw the entire incident. To find out what really happened the night of the murder, Isaiah must piece together clues from each of the personalities—before the cops catch up.

Release date: January 28, 2020

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hi Five

Joe Ide

Isaiah Quintabe’s East Long Beach neighborhood hadn’t changed much over the years. It was the hood when he was growing up and it was the hood now. Gangs, street crime, poverty, drugs, and violence were constants, facts of life. Isaiah didn’t know the statistics but from his perspective, things were getting worse. Not a surprising viewpoint when your job was fighting human suffering and indifference.

As the area’s only unlicensed PI and unofficial ombudsman, there wasn’t much he hadn’t seen. Murders, robberies, burglaries, scams, bullying, kidnappings, addiction, rape, child abuse, loan sharking, questionable suicides; runaway children, husbands and wives. There were cases of great consequence and those of very little, but all were crucial to the victims, whatever the size of the injustice.

Someone had stolen Mrs. Marquez’s Pomeranian, Pepito, and was holding it for ransom. The kidnapper left a note on her porch. There was a phone number and a demand for five hundred dollars or your dog will be drownded in the ocen. She called the number while Isaiah listened in.

“Yeah?” the man said. “Who’s this?”

Isaiah immediately recognized the voice. It was Freemont Reese, a young hooligan who was so stupid and cowardly even the gangs rejected him.

“This is Mrs. Marquez,” she said. “You stole my dog?”

“I sho’ did,” Freemont said. “Did you read the part about the money?”

“How do I know you have him?” Mrs. Marquez said, Isaiah nodding his approval.

“Because it’s sitting right next to me watchin’ TV. You want me to put him on the phone?”

“I mean, what’s the dog’s name?”

“His name? I don’t know. He hasn’t told me yet.”

“It’s on his tag. You know, the one hanging on his collar?”

Freemont told her to meet him at McClarin Park and sit on the bench nearest the south entrance. “You better have the money,” he said. “Or you can go get yourself a cat right now.”

Mrs. Marquez went to the park and sat on the designated bench. She had twelve dollars in her purse. Isaiah stayed well back and watched. He spotted Freemont near the restrooms, peeking around a corner. He didn’t have the dog. Isaiah circled and got behind him.

“How are you, Freemont?” Isaiah said.

Freemont jumped. “Hey, man. Don’t be sneakin’ up on me like that! I might have shot your ass.”

“With what?” Isaiah said. “The gun you have in your sock? Where’s the dog?”

“What dog?” Freemont said, just realizing it was Isaiah.

“The one that belongs to the collar you have in your hand.”

“This? I found it.”

“Where’s the dog?”

“I don’t have to tell you nothin’, Isaiah, and you can’t make me.”

“No, I can’t, but I know who can.”

“Oh, yeah?” Freemont sneered. “And who is that?”

“Your mother,” Isaiah said.

Freemont’s face crumpled in on itself like a wadded-up napkin. “Hey, man,” he said, putting his palms out, his voice rising an octave. “She ain’t got nothin’ to do with this.” Freemont lived with his mother, Oleta, a bony, fearsome woman with no sense of humor and nails jutting out of her eyes.

“Do you remember that time I helped her out?” Isaiah said. “Her boss at the shoe store wouldn’t pay her overtime and I made him give it up? She was grateful. Really grateful.”

Freemont shook his head and looked to the heavens. Maybe someone up there would have his back.

“Bring me the dog,” Isaiah said. “And if there’s a scratch on him, I’ll lock you in a room with Mrs. Marquez and a baseball bat.”

Mrs. Marquez was thrilled to get Pepito back, and she brought Isaiah a soul-warming pot of calabacitas con puerco, a hearty stew of vegetables, spices and pork cooked in butter. Isaiah wished she had more dogs that were stolen.

He was happy to have helped her like he was happy to help anybody, but lately he’d been wondering if he had a higher calling. The traditional notions of success bored him. He had a nice place to live, food on the table, and a fast car to drive. Getting a nicer place, more food on the table and a faster car didn’t interest him at all. A lot of people seemed to enjoy power. Controlling the lives of others, telling them what to do, determining their fates—the idea made him cringe. He could barely control his own life, let alone determine his fate. Isaiah in charge of Isaiah was plenty. Maybe he should just shut up and get on with it.

He had a girlfriend now, Stella McDaniels. They’d been seeing each other for three months. She was a violinist, first chair, in the Long Beach Symphony Orchestra. He’d met her on a case. On her way to rehearsal she’d stopped at Beaumont’s store to get a bottle of water. She was late and didn’t lock the car. When she returned, her violin was gone. A Giovanni & Giuseppe Dollenz violin made in Italy circa 1855. When she was in high school, her parents had used their life savings and cashed in their IRA to buy it for her. The instrument was insured for fifty thousand dollars, but over the years it had increased in value and the payout wouldn’t cover the cost of anything comparable. The symphony season was starting and she was frantic. She got a rental but it was like wearing someone else’s shoes, the same thing but unfamiliar, and when you’re playing music at her level, feel was everything.

Stella had come up the hard way, like Isaiah, like everyone in the neighborhood. Her family lived on the border between Long Beach and Compton, the hood if there ever was one. Isaiah asked her when she knew she was going to be a musician. “I’ve always known,” she said. “There was never a day I didn’t know.”

Her parents were working people and couldn’t afford music school or even music lessons. She used a relative’s battered, tinny-sounding instrument and practiced relentlessly. A friend of her mother’s owned a laundromat. At age nine, Stella was sorting lights and darks, stuffing wet clothes into the dryers and folding sheets by herself. She used the money to pay for music lessons, but she could only afford three. The teacher recognized almost immediately that Stella was exceptionally talented and lowered her rates to next to nothing. In high school, Stella worked two jobs after school and in the summer. She got a better teacher, played in junior orchestras and earned a music scholarship to the California School of the Arts. She entered competitions but was disappointed. There were other exceptionally talented violinists who were better than her. She would never command an audience of her own.

After graduation, she gave violin lessons to children, taught music at a small college, substituted in local orchestras, played in Vegas for Michael Bublé and finally, finally, got a spot in the Long Beach Symphony. It took her seven years to work herself up to first chair. A prestigious position. She was the principal soloist as well as leader of the section. The other musicians would take her directions on inflection, dynamics, bowing and numerous other things. Her first solo would be her proudest moment and the proudest moment for her family.

Where to start? Isaiah thought. East Long Beach had a legion of car thieves, but the violin had been stolen right outside of Beaumont’s and she’d been inside the store for only a minute, two at the most. Someone was Johnny-on-the-spot. A local walking by or someone on his way into the store. Beaumont’s was in gang territory. Locos Sureños 13.

Isaiah went to see the gang’s entrepreneurial leader, Manzo. They weren’t friends but they respected each other and sometimes traded favors.

They met at Café Michoacán, Manzo’s new coffee place. Manzo was thirty-five or so, dressed in nice chinos and a black shirt, inked-up, bulked-up arms coming out of the sleeves. He was the only gang leader Isaiah had ever heard of who invested the gang’s money. Manzo had told Isaiah he was going to open a Starbucks for Mexicans and here it was. Clean, modern, comfortable seating, display cases for Mexican pastries and beautifully embroidered story cloths on the walls. Mexican jazz was playing. Isaiah thought he recognized Juan José Calatayud but he could have been wrong. The place was nearly full. A mix of young and old staff. Not a Corona poster or a sombrero in sight. It could have been an actual Starbucks save for the solidly Latino faces.

“Cool place,” Isaiah said. “Congratulations.”

“Yeah, it came out better than I thought,” Manzo said, sipping his latte. “Another year, we’ll be profitable. I’m thinking about a franchise.” Manzo funded his enterprises with drug money so he had no loans to carry. “You think it’ll go?”

“I don’t see why not,” Isaiah replied.

Manzo’s stated mission was to get his gang off the street but so far, he hadn’t succeeded. The members who signed on for the investments didn’t quit banging or dealing. The dividend checks were another income stream that paid for the same shit gangstas always dropped their money on: weed, guns, electronics and cars.

Isaiah told Manzo about Stella.

“A violin can be worth that much?” Manzo said.

“I guess so. I don’t know much about it.”

“Who’s Stella?”

Isaiah shrugged. “Client.”

Manzo smiled. “Is she paying you?”

Isaiah smiled back. “Do I ask you about your personal life?”

“I’ll talk to the fellas about your violin,” Manzo said as he got up. “Coffee’s on the house.”

Manzo put the word out to the homies who put the word out on the street. The khan of the Locos wanted the violin and if you happened to have it in your possession, your best option was to return it or suffer a life-threatening injury. Two days later, it came back. There were a couple of new scratches on the fretting board and a dent on the scroll, but they were cosmetic.

“Alfredo had it,” Manzo said. “He gave it to his eight-year-old daughter as a birthday present.”

“Thanks,” Isaiah said. “I owe you one.”

“I know.”

It cost Isaiah a favor but it was worth the effort. Stella was nice to look at and a good listener, sifting through your words like she was panning for gold. She talked about music with intensity and passion, and Isaiah wished he still felt like that about his work. Stella was a few years older and had been through the relationship wars. She said she was done with being cool, buying cool things, hanging in cool places and, most of all, cool men.

“I’m not cool?” he said.

She smiled. “No, you’re not. And that’s what’s cool about you.”

Isaiah was driving over to Stella’s place thinking about how he envied her and wished he’d taken a path like hers instead of his own. To be brilliant at something the world recognized. He wondered what that could be. His brother, Marcus, had told him many times, he could be anything, do anything he wanted, and nothing could stop him but himself. Was that true? Could he really be anything he wanted? Maybe so, if he knew what that was.

He was nearing Stella’s place when he saw Grace. He did a double take and nearly rear-ended the car in front of him. He couldn’t believe it. Was it actually her? He hadn’t seen her in two years, since she’d left for New Mexico and taken his heart with her. She was going in the other direction, driving the same ’09 white GTI. The New Mexico sun had burnished her skin, the pale green eyes hidden behind mirrored sunglasses, her hair tucked messily under a baseball cap. Isaiah had given her his dog, Ruffin, for protection, and there he was, head out the window, tongue flapping, happy as could be. Isaiah who? In an instant, Grace was past him. He tried to make a U-turn but was boxed in by the traffic. He yanked the car over into a red zone, got out and clambered onto the roof. He stood on his tiptoes and craned his neck, but the GTI was gone.

He was confounded. Why had she come back? How long had she been here? His heart was thudding like he was mid-marathon and losing. Was she back for good? The car still had its California plates. Why hadn’t she called him? Had she forgotten him? Or maybe she’d just arrived. Yeah, that made sense. She’d made the long drive and wanted to get herself together before they met.

Except her car was clean. No road dust, no bugs on the windshield, so she’d been here long enough to get her car washed, and he didn’t remember her ever wearing sunglasses or a cap even on sunny days. Maybe that was something she picked up in New Mexico. Sure, that was it. It was hot out there—but it was hot here too. Maybe she was hiding from someone and in disguise. Maybe she was hiding from him. He felt hollow and a little sick. The torch he’d been carrying all these months had smoldered but never gone out. He could feel it crackling into flames again. What to do? Track her down? It was tempting, but wait, he told himself. Calm down. She has her reasons. Be patient. She’ll call. She had to, didn’t she?

Chapter One

Beaumont’s corner store, Six to Ten Thirty, had been a fixture in the neighborhood for more than thirty years. Like people his age tend to do, Beaumont wondered what his life had been about, stuck here in this cramped, un-air-conditioned space with the Red Vines, the packages of Kotex, the cans of frijoles, the racks of chips and coolers full of Budweiser, the hard liquor behind the counter. There was a time when he thought about moving on, doing something else, going someplace where he could be outdoors and breathe some clean air. But after his wife, Camille, died, he didn’t see the point. Why bother being anywhere in particular if the love of your life wasn’t there with you? Beaumont had two grown children. Merrill was a traffic engineer in San Diego. His daughter, Katrice, was locked up in Vacaville for carjacking. These days, one out of two wasn’t bad.

Beaumont heard rowdy voices coming up the street. He sighed, dreading their arrival. It was never a group of police officers or a troop of Boy Scouts or some other kind of law-abiding folks, and sure enough, four hooligans from a Cambodian gang came in with their white T-shirts, gold chains and tattoos. Maybe one of these days somebody would break the mold, wear a bowler hat or some penny loafers. The chubby one was the shot maker or shot supervisor or shot daddy or whatever they called the ringleader these days. In Beaumont’s eyes, the kid didn’t look any different from the others, but that’s what they used to say about black folks so he crossed that off his observation list. He wondered if there was a nationality left that didn’t have gangsters. Even white people who’d never been closer to the hood than one of Biggie’s CD covers walked around talking like they’d been born in East Long Beach with a Glock 17 in their nappies.

The Cambodians dispersed into the store. There were fish-eye mirrors everywhere but these guys were past shoplifting. They had money. They still made Beaumont nervous but he wasn’t afraid of them. He’d been in Vietnam and had seen action that would have these punks crying for their mamas.

They came back with a pile of junk food and dumped it on the counter.

“How you doin’, Chief?” Chubby said. He was the leader for no apparent reason Beaumont could see.

“I’m doing just fine,” Beaumont said.

“I been meaning to ask you. What do you do with yourself all day besides sit back there and jerk off?”

“And I’ve been meaning to ask you,” Beaumont retorted, “what do you do all day besides lie around being an asshole?”

Chubby slow-blinked twice. “You know, one of these days your store might burn down.”

“And one of these days your mama’s house might catch on fire. I know where she lives, son.”

Chubby tightened up and let one shoulder sag like he was going to throw a punch. Beaumont put his hand under the counter. He hadn’t fired the .45 Colt Commander since Phnom Penh but the gesture made Chubby hesitate. The moment teetered on the edge of violence.

One of the other guys said, “Hey, fuck this guy, Lok. We got shit to do.”

Chubby had his eyes locked on Beaumont’s. “I’ll be back, Chief.”

“And I’ll be right here,” Beaumont replied.

Beaumont thought he might clean the gun, see if it still fired when he heard a big engine revving and the Cambodians shouting get down! The salvo of bullets came through the window like copper hornets, spider-webbing the glass, exploding the tiny boxes of Tide, cans of chili and SpaghettiOs, the coolers shattering, the whole candy section blasted apart, a confetti of paper towels and toilet paper fluttering in the air.

Beaumont couldn’t get down fast enough. He’d barely bent his knees when he was hit in the shoulder. “Oh God, I’m shot!” he shouted. Then the second and third bullets struck him in the chest. He twisted around, grabbing at the shelves and sliding to the floor, dragging bottles of Smirnoff and Early Times down on top of him, a fleeting, silver moment of consciousness streaking past as he closed his eyes and the world was gone forever.

Isaiah was on a case and didn’t hear about the shooting until the next day. Dodson came over to tell him.

“Beaumont?” Isaiah said. “They shot Beaumont?” Dodson looked the same, maybe a little heavier, but the same. Homeboy uniform, short, cocky, swagger in his chromosomes.

“I talked to his son,” Dodson said. “He said Beaumont’s hurt bad, doctors don’t know if he’s gonna make it. You want to go to the hospital?”

“No, the store first.”

Isaiah and Dodson hadn’t worked together since the 14K Triad case. The partnership had gone bust, but since then they’d fallen into an easy comradery that Isaiah cherished. It was the most solid, reassuring thing he’d had in his life since Marcus was killed. As long as he and Dodson didn’t spend too much time together, the relationship worked fine.

“I’m telling you, this gun shit is getting out of hand,” Dodson said. “I was over at Raphael’s crib buyin’ some weed? Three of them East Side Longos was there and check dis. They all had brand-new Berettas, that compact model? Julio said the whole damn gang has them. They bought them like team jerseys.”

“How’s Micah?” Isaiah said.

“He’s doing aight,” Dodson said. “Big-head boy thinks he can walk, stumbling around with his feet all wide apart, little hands up in the air, and making goo-goo noises that Cherise says are words. That’s a fortunate lil’ muthafucka, growing up proper-like. Got love all around him, don’t have to worry about nothin’.” Dodson’s face didn’t match the words. He seemed far away and brooding. Strange for him.

“You okay?” Isaiah said.

“Yeah, I’m cool. I think I’m coming down with a cold.” Isaiah didn’t believe him. Dodson’s gears were grinding on something too private to talk about.

Isaiah had heard about him only sporadically. After the Walczak case, Grace’s mother had given Dodson a not-so-small fortune. That was a while ago and he hadn’t mentioned it since. A couple of times, Isaiah saw him driving a tow truck. Dodson had seen him but pretended he didn’t. Isaiah wondered what that was all about and whether his friend was hustling again.

The police had come and gone. Beaumont’s store was boarded up, yellow tape hanging loosely across the open door. Isaiah and Dodson had known Beaumont since they were kids. The crotchety old man was one of the good, hardworking people who made up most of the neighborhood. He’d never hurt anybody or caused any trouble. He ran his store, loved his family, smoked a cigar in the park on warm evenings and went fishing with TK and Harry Haldeman. Now he was dead for no reason at all. Isaiah hated the term “random violence,” as if it were an anomaly, worrisome only if you were unlucky, and not a plague on the community that infected everyone with the belief that killings were an ordinary part of life.

“This is bullshit,” Dodson said, shaking his head in disgust. “Muthafuckas ain’t got nothin’ better to do than kill people minding they own business?”

Isaiah said, “Do you know what happened?”

“Drive-by. Around one in the afternoon,” Dodson said. “No witnesses.” The bullet holes in the store’s façade were large, wood splintered around them. “Big-ass bullets,” Dodson noted.

“Could have been nine-millimeter but I’m thinking .45s,” Isaiah said. Dodson looked at the splotches of dried blood on the sidewalk where a gangsta had been hit.

“I hope he died,” Dodson said. “Lok’s people were the ones that got shot at. Cops haven’t identified the shooters. They were on the news asking for help, which means they don’t know shit.” Isaiah shook his head. One third of the murder cases in the US go unsolved and he was fiercely determined Beaumont’s wouldn’t be one of them. He put his hands in his front pockets and looked off a moment. “Let’s talk to Mo.”

Across the street from Beaumont’s was a vacant storefront that used to sell vacuum cleaners. A wino named Mo camped out in the vestibule for part of the day. He used to hang with another wino named Dancy but Dancy died of liver cancer. Nobody knew he had it until the coroner found a tumor as big as a fist. None of the other winos could remember saying Mo’s name without saying and Dancy. Mo still said it, though his friend had died months ago.

Mo was sitting on a greasy sleeping bag with his back against the door, eating noodles from a Styrofoam cup. His shopping cart full of overstuffed garbage bags was parked beside him. He’d probably tried to flee when the shooting happened but it was a drive-by, over in seconds.

Isaiah and Dodson approached him.

“Hey, Mo,” Isaiah said.

“How you doin’, Isaiah. Is that you, Dodson?”

“Yeah, it’s me.”

“Bad day,” Mo said, shaking his head. There was lint in his gray hair, hands as dirty as the sidewalk, his layers of clothes stuck together with grime. “Beaumont was a good man. I cried like a baby when I heard he was dead. Seems to be goin’ around. Wasn’t no cause for that. No cause at all.”

“You saw the whole thing, didn’t you?” Isaiah said, going right at him.

Mo choked on some noodles and wiped his mouth on a sleeve infested with every germ in the world. “No, I didn’t. I didn’t see nothin’. Wasn’t even here.”

“Mo—” Isaiah said, a warning in his voice.

Mo slurped down the last of the noodles. “I see no evil, hear no evil. That’s the only way to get along out here.”

“You saw everything, start to finish.”

“Imm-possible,” Mo said with a sharp nod. “I wasn’t even here.”

“Stop lying, Mo. In the morning you hang out around the Coffee Cup because Verna passes out leftovers, and then around lunchtime you come over here because Beaumont gave you a free beer if you swept the sidewalk and kept the trash area clean. You were here, Mo.”

“How you know all that?” Mo said. “You been followin’ me?” Isaiah glared. Mo cringed. “Okay, okay. Y’all don’t need to be like that. Ain’t much to tell no ways. Some thugs went into the store, came out again, and then this pickup goes by, somebody on the passenger side started shooting. Br-d-d-d-d-d-d-it! Just like that.”

“Was it loud?” Isaiah asked. “You’ve heard gunshots before.”

“Shits yeah it was loud. Almost broke my hearin’ system.”

“What kind of truck was it?” Dodson said.

“You mean the brand? I don’t know. Ain’t had a car since I drove through a fence and landed in some lady’s fish pond. Big fish in there, orange and white. When the lady stopped screaming at me, she said some of ’em was a hundred years old. You believe that?”

“Color?” Isaiah said.

“Like I said, orange and white.”

“I mean the truck.”

“Black.”

“Did you see the driver?”

“He went by real fast,” Mo said. “But it was a white boy, had a cap on backwards, you know how they do.”

“You sure it was a white boy?” Dodson said.

Mo nodded adamantly. “Positivity,” he said.

“Anything else stand out to you?” Isaiah asked. “Anything at all?”

“No, I don’t think so. You believe that lady’s fish was a hundred years old?”

Intensive Care was a familiar scene to Dodson. He’d been here many times in his gangsta days, the room dim, his homeboy diminished and frail no matter what his size, the badass bled out of him, lying there in a mess of tubes, white tape and catheters, family members crying and solemn, like the boy’s life meant something, the slow beeps and barely oscillating lines warning you the end was near. Save for the medical equipment, Beaumont might have been lying in state.

Beaumont’s son, Merrill, was there. The old folks described him as a nice young man; a ranking just below TV star in the hood. Merrill was standing next to the bed. Dodson and Isaiah shook Merrill’s hand. The only things Dodson could think of to say were clichés. Probably the same with Isaiah.

“He respected you, Isaiah,” Merrill said. His eyes were bloodshot and brimmed with tears.

“And I respected him too,” Isaiah said.

“I appreciate you coming, Dodson,” Merrill said. His tone suggesting Dodson’s presence was as unexpected as it was unnecessary.

“I’m sorry for your loss, Merrill,” he said. “Beaumont was a good man.”

Glints of anger sparked off Merrill’s eyes and he turned away. Dodson knew why. He was one of the kids that stole from Beaumont’s store and told him he charged so much he must be a Jew and painted graffiti and pictures of big dicks on the walls and said shitty things about Camille when she was bald and stripped down to the bone with cancer.

Merrill said, “Dad is gone and he won’t recover. I’m waiting for his sister to arrive before I pull the—” He wiped the tears off his face with his shirtsleeve. “Before I end it.” He took his father’s hand.

Dodson, Merrill and Isaiah had known each other since middle school. Merrill and Isaiah were good students and hung out with other good students. Dodson was on the other side of the playground, smoking weed with the fellas and trying to convince girls to meet him in the bathroom.

Dodson lived across the street from Merrill. They’d watched each other grow up with the wary, amused contempt of rival religious groups. Dodson and his crew taunted Merrill at every opportunity; about his pastel polo shirts and his fucked-up haircut and his lame-ass backpack. They would have beat him up for sport if Beaumont hadn’t known all their parents.

Dodson’s father threw him out of the house when he was seventeen. Nobody would take him in and he was living in Lateesha’s car with the Saran Wrap windows and cat hair fossilized in the seats. It was a school morning. He woke up with crust in his eyes, Buckwheat hair and the taste of weed and cheap wine in his mouth. He was standing at the curb, brushing his teeth and rinsing his mouth out with a warm Dr Pepper. He was just realizing how stupid that was when Beaumont drove by. Merrill was in the passenger seat. They made eye contact, a moment so humiliating Dodson wanted to shoot him.

Dodson and Isaiah left the hospital room, Isaiah with that look on his face, the one that said he was pissed off and wasn’t going to let this go. Dodson was angry too, but for some reason, he couldn’t get his mind off Merrill, standing at his father’s bedside holding his hand.

Dodson had to babysit Micah, so he drove Isaiah home. He stayed distant and tight. Not like him. He was usually talkative to the point where you wanted to put your hand over his mouth. A tension crept into the car, the imminent kind, where something important was going to be said and it was only a question of when. But nothing happened.

“Thanks for the ride,” Isaiah said as he got out of the car.

“Yeah, I’ll see you later,” Dodson said.

Strange, Isaiah thought, that Dodson had come over in the first place. He could have told him about Beaumont over the phone. There was something weighty on his friend’s mind. He’ll talk when he’s ready, Isaiah decided, knowing that was true about himself.

He ate a bowl of oatmeal standing at the kitchen counter and thought about Grace. Where she was, what she was doing and who she was with. Why hadn’t she called? He imagined a dozen scenarios. She had a deadly disease, she was disfigured, she was homeless, she lost his phone number, address and email all at the same time. Or maybe she had amnesia or had become a heroin addict, joined a cult or was married with a couple of kids. He was driving himself crazy so he went to Ari’s gym to work out.

Ari taught Krav Maga, a mixed martial art developed by the Israeli military. Isaiah had been attacked and beaten numerous times over his career. Belatedly, he’d realized he should take self-defense more seriously.

Ari was the same as he’d always been. Built like a concrete pillar, silver hair in a flattop, fists big as sledgehammers.

“Let’s go, Isaiah,” Ari said. “Show me what you’ve learned.”

They sparred, Ari saying, “Too slow, Isaiah. Isaiah, keep your balance. You are leaving yourself open, see?” as he slammed him to the mat.

“Don’t you think you could be a little encouraging?” Isaiah said.

“Maybe later,” Ari said, pulling him to his feet. He put his hands on Isaiah’s shoulders and looked like a father sending a son off to war. Ari knew what wars were like and for him, they were never over. “Remember, Isaiah,” he said. “Fight to win, and it doesn’t matter how. Don’t stop, don’t give up. Whatever you do, keep f

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...