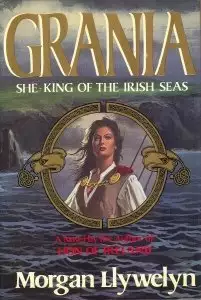

Grania

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Here is an extraordinary novel about real-life Irish chieftain Grace O Malley. From Morgan Llywelyn, bestselling author of Lion of Ireland and the Irish Century novels, comes the story of a magnificent, sixteenth-century heroine whose spirit and passion are the spirit and passion of Ireland itself.

Grania (Gaelic for Grace) is no ordinary female. And she lives in extraordinary times. For even as Grania rises as her clan's unofficial head and breadwinner and learns to love a man, she enters a lifelong struggle against the English forces of Queen Elizabeth -- her nemesis and alter ego.

Elizabeth intends to destroy Grania's piracy and shipping empire--and so subjugate Ireland once and for all. But Grania, aided by Tigernan, her faithful (and secretly adoring) lieutenant, has no choice but to fight back. The story of her life is the story of Ireland's fight for solidarity and survival--but it's also the story of Grania's growing ability to love and be strong at the same time.

Morgan Llywelyn has written a rich, historically accurate, and passionate novel of divided Ireland -- and of one brave woman who is Ireland herself.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: February 20, 2007

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Grania

Morgan Llywelyn

She-King of the Irish Seas

Morgan Llywelyn

I

The fire was only a spark at first. Anyone who saw it could have extinguished it. But no one did.

In the darkest watch of the night, a sailor from the forecastle had crept to the rail and glanced around nervously, making certain he was unobserved. From beneath his tunic he had slipped a small metal case, a pierced-brass body warmer given him by his wife. Her man suffered chills and fever but had insisted on going on this voyage anyway. Their cottage overflowed with children, and a crewmember's portion of the profit the captain so generously shared would support the whole family.

The sailor had concealed his illness as best he could when he came aboard, for he meant to haul his share of tackle. But soon after they set sail his bones began shivering in their envelope of flesh. When the ship anchored off the coast for the night, he sneaked below to the brick cooking hearth, bedded on gravel ballast in the hold, and stole some hot ashes for his warming pan. Wrapped in flannel and pressed against his chest, the warmer offered welcome comfort.

He knew he was breaking a cardinal rule of the sea. None but the cook was allowed access to the hearth, for fire was the terror of timbered sailing ships. When his pan cooled, the man had surreptitiously emptied the ashes over the side and replaced them with a hand fishing line and some bobbers, innocent equipment most seamen carried in packets on their persons.

He was so concerned about being discovered he did not notice that a small coal among the ashes was still warm. As he pitched it over the side, the wind caught a living spark and blew it back inboard, dropping it into a coil of tarred rope in the waist of the vessel, out of sight behind the ship's boat

The sky paled and the wind calmed, then freshened, making the great sails creak overhead. The half-hour glass, made in Venice and so fragile the ship carried several spares, was turned and turned again. The watch bell sounded. Seamen exchanged places. Some went to their hammocks in the forecastle or their favorite corner of the deck where they could brace themselves against the pitch and roll of the ship; others, rubbing their eyes, went shuffling to the break in the poop to relieve themselves and then lined up for a meal of oatcakes, cheese, and onions. A fresh lookout was posted fore and aft, and the ship's boy made his way to the captain's cabin, carrying a meal in a wooden bowl. The anchor was hoisted, the ship under way.

And in its hiding place the spark grew a little red tongue and began tasting the frayed fibers of its rope nest. The waist of the caravel was low and often awash in a high sea, and the rope was far from dry. But the tiny fire was stubborn; it meant to survive.

A fair wind was blowing by now, and the caravel was an eager ship. Accompanied by two galleys, she was on a trading voyage intended to follow the southern coast of Ireland as far as Wexford harbor, having originated northwest of Galway bay. Wool and tallow from Iar Connaught waited in her holds for eager southern customers, and the clansmen of Iar Connaught waited just as eagerly for the goods she would bring back in return.

The older crewmen were hard at work manning halyards and tending tacklings, while their younger, more agile mates served as foremastmen, furling and slinging the foresail as needed or scrambling aloft to tend the great fore-and-aft lateens that furnished the ship's principal motive power. On a tossing deck, footing was precarious enough, but for a foremastman aloft, with bare prehensile toes clinging to ratlines or muscular torso stretched out along a yardarm, life was uncertain from one heartbeat to the next. A misstep, a lost handhold, and the sailor could be pitched headfirst into the sea. In common with seamen everywhere, the crewmen of the caravel were not swimmers. Their trust was in their ship and captain…and their God.

On the morning watch, the youngest apprentices scrubbed the decks with seawater carried from a tub amidships. Keeping that tub filled was hard work, and dangerous, because the boys had to lean far out in order to lower their leather buckets into the sea, and if the caravel wallowed it was easy enough to go overboard. Once the tub was filled there was no danger but the tedium of the task, which the apprentices relieved by singing and joking as they worked, sweeping the planking with coarse brooms and taking up the remaining moisture with mops made from rope-ravelings.

There was always one boy who held his mop to his head so the ravelings lay like curls against his cheeks, while he pranced and played the girl and the others cheered him on. The decks rang with laughter and the old seamen scowled, but their eyes twinkled with memories of their own as the lads frolicked. The apprentices were mostly red-cheeked young Gaels from the hills of Connaught, with a taste for adventure. The sea had not yet turned on them, and it was a fine thing to be part of a bold venture off the coast of Ireland on a summer morning.

One freckled boy, naked except for a pair of woolen trews chopped off at the knee, trotted up to the tub to refill his bucket for deck swabbing. He hesitated, wrinkling his nose at an unfamiliar smell. He was a rawboned, merry lad, and the sea was new to him. Until he came aboard for this voyage he had never been off dry land, and he did not yet know what sights and scents were commonplace to a four-masted caravel under full sail. But instinct warned him the odor of scorching rope and charring wood was wrong here—terribly wrong.

Taking another sniff, he tried to isolate the smell from that of salt and tar and bilge. "Something's burning," he said tentatively. He did not want to make a fool of himself over nothing. The men who sailed on ships such as this—ships that sometimes engaged in piracy as well as trade—were the cream of their profession, hardbitten and courageous. They would make life miserable for anyone who acted timid, crying false alarms.

But the smell was growing stronger.

Then a shrill voice screamed, "Fire! Fire!" The boy did not realize it was he who screamed. He stood rooted to the deck, staring in horror at a sudden banner of red flame leaping above the ship's boat and dancing in the seawind.

"Fire!" cried a dozen other voices at once. There was no hesitation, because every man on board knew what fire could do at sea, where there was no way to escape from it. Men came swarming from every direction, ripping off their clothes to beat out the flames, shoving the boy aside in their hurry to get at the mop water in the tub. Somebody grabbed the bucket out of his hand and filled it and then threw the water at the fire in one smooth gesture, and the boy heard the fire hiss. But one bucket was not enough to drown it; the contents of the depleted tub were not enough to drown it.

The fire took a deep breath and roared.

"Send for the captain!" shouted the boatswain's mate as he began trying to haul the ship's boat, his particular responsibility, out of the way. The waist of the vessel was crowded, and there was little room to work. Other men joined him and grunted and tugged until the boat scraped forward, but the fire billowed into the cleared space like a beast released from a trap. It had already ignited the far side of the ship's boat, and from there was reaching for the mainmast.

"Keep it out of the rigging!"

Sailors pressed forward, beating at the flames, as an acid, tarry stench seared the nostrils. The rising wind encouraged the fire to leap higher, snatching at the lateen sails.

An inferno was being born. It exploded savagely, driving the men back. If fire got into the sails the ship was lost; falling spars and burning sheets would set the whole caravel ablaze.

There was more to fight than fire. Panic rippled through the crew, and they

reacted reflexively, without plan, running from this spot to that and getting in each other's way. The country boy who had first spotted the fire had no idea what to do, and no one was able to tell him. He looked longingly toward the gunwales and imagined plunging into the cold sea. Drown or be burned.

His eyes dilated with terror.

"Look out, boy!" cried a voice roughened by years of shouting commands. Hands gripped his shoulders and flung him violently to the deck just as a burning shroud snapped overhead and whipped through the air.

The apprentice was thrown forward. His cheekbone struck planking, and stars of pain shattered in his skull. He heard the vicious whoosh of the blazing line as it passed over him. He heard the scream of agony as it hit another man full in the face, searing his eyes.

"Get up now, you're in the way lying on deck," demanded the boy's rescuer. He recognized that voice, for he had heard it often since coming aboard, giving orders or requesting information or whooping with a great wild peal of laughter. Everyone knew the distinctive voice of the commander of the fleet and captain of this ship, a being with one foot already planted in legend.

The commander grabbed the boy under the arms and hauled him upright, where he stood shivering and speechless, mouth agape.

"You could thank me," he was told. The eyes that met his were the shifting color of the sea, but he caught a glimpse of laughter in them.

"Th…thank you," the lad stammered, hating himself for his awkwardness.

The fire would not wait for formalities. The commander could not waste time with an apprentice while the greater life, that of the ship itself, was threatened. She turned away abruptly to take up the battle for the caravel, and the boy stared after her, blushing crimson.

"Gráinne Ni Mháille," he whispered in Gaelic. "Grania."

The commander of the fleet was tall and lean, taut-muscled. The English would translate her name as Grace, but she was no milk-skinned girl in a laced bodice. Aboard ship Grania, in her early thirties, wore a man's sleeved shirt, a fustian jerkin, and worsted trews. Her coarse black mane was knotted at the neck to keep it out of her way. Heavy eyebrows cut a straight line across her strong-boned face, and her complexion was weather-beaten, squint lines framing the eyes. At a glance she could be mistaken for one of the Gaelic warlords who still struggled to hold their native Ireland against the encroachment of Elizabeth Tudor's England.

To the boy she had just saved, Grania was beautiful. His awed gaze followed her until she plunged through a wall of smoke and disappeared; his shoulders prickled where she had touched him.

She could not help seeing the admiration in his eyes, but she had been thinking of her ship; nothing else mattered just then.

* * *

The caravel had been Grania's special joy since the day its keel was laid to her order in the shipyard at La Coruña, the same Spanish port from which the first Gaels had set out to colonize Ireland two thousand years earlier. The chief shipbuilder had personally conducted the formalities of turning the completed vessel over to her new owner, because he was an old friend of Grania's father, the redoubtable Gaelic trader Owen O Malley. Dubhdara, in Gaelic—the Black Oak.

Everyone for miles around came to the harbor at La Coruña to admire the black-hulled ship, graceful as a tern, with her spars of golden wood gleaming in the sunlight. Adhering to tradition, the wives and children of the men who had built a caravel for Dubh-dara's daughter threw armloads of flowers into the water; there were bonfires of celebration, and singing.

The old master shipbuilder told Grania, as she took possession of her new vessel, "The ships I build are demanding children. You cannot abuse or deceive them or they will find the weak planking in you and split you wide open. But if you treat them well, they will support you handsomely in your old age."

This was not Grania's first visit to Spain, for she had come on trading voyages with Dubhdara, but it was her first caravel, and she thought it the most beautiful vessel ever launched. She had worked hard to acquire enough money to commission it; she had earned every timber and line herself. Herself.

The caravel belonged to the general family of round ships but had narrower quarters and was faster than many of her contemporaries, better fitted for maneuvering. Grania's new ship had a square stern, fore and aft castles, and a foremast raked well forward, giving her a jaunty look. Her cargo holds were capacious, and her forecastle bulkhead had been pierced for cannon. She was a serious ship, a cargo carrier with teeth.

Dubhdara, who relied primarily on galleys, as did most Irish seafarers, possessed a caravel or two for voyages to Spain and other distant ports, but nothing in his fleet was as fine, as modern, as Grania's new flagship.

"Mine," she had breathed with delight as she took possession.

Before they were outlawed entirely, the few remaining bards sang in her honor in the peat-smoked meadhalls of Ireland:

* * *

By rock-ribbed Connaught my swift vessels glide,

Like swans they are breasting the full-flowing tide.

Warships and Gaels all ready to sail,

To sweep the salt sea from Cape Clear to Kinsale.

* * *

Warships and a warrior woman to lead them: the numerous songs sung of her were repeated across the west country, from the time she took command of that first splendid caravel.

* * *

And now the very survival of the caravel was threatened. Flakes of wood ash fell like bitter rain. Greasy particles of burning hemp writhed in the air like tiny blazing snakes and clung, stinging, to human flesh.

The first mate caught sight of his captain and ran to her side. "What are your orders?" Tigernan wanted to know as he rubbed the smoke from his eyes.

"If we bring her up into the wind," Grania replied, "we might be able to drive back the fire and contain it."

Tigernan shook his head. "We can't bring her about—the running rig's already too damaged. And many of the shrouds are burned through. We could be dismasted by the next real gust of wind. As for the helmsman …"

"I know, I saw him aft, with his hands like cooked meat and his mustache half burned away. But we have to save the ship. And if we can't use the sails …" She tilted her head back and gazed aloft, narrowing her eyes. "If we throw them overboard with the rigging still on them, they won't be burned and we can retrieve them later," she decided swiftly. She raised her voice to a commanding bellow. "Dowse all sails and pitch them into the sea!"

Tigernan repeated her order, a necessary precaution aboard ship, where a misunderstood command could lead to disaster. The crew immediately began lowering the sails, foremastmen swarming up the ratlines on the windward side to free the sheets from their yards.

Grania watched the big lateen sails being thrown into the sea. They lay outstretched upon the water like the wings of a fallen swan.

She blinked hard, then shouted the next order. "You there, find every bucket or bowl or cask on board, get them over the side and filled with water. And you to the forecastle; those other men to my cabin. Strip out every piece of material that can be used for beating the flames. And hurry, it's gaining on us!"

Putting word to action, Grania pulled off her own jerkin and shirt and whirled bare breasted to lash at the fire.

Yet with every blow she struck she felt a thrill of fear. She had watched from the shore of Clew bay as burned bodies were washed in by the tide from a ship that blazed and sank within sight of land, a doomed ship not one survivor escaped. The story was commonplace enough: a mast struck by lightning or a lantern carelessly handled. But the memory of those charred, twisted bodies stayed with Grania a long time, and it came back now in a sickening wave.

For one moment her mind was blank with terror. Then she gasped and beat at the flames with redoubled effort, submerging memory in motion. Fear had to be set aside or it would swamp her—and the caravel too.

With an effort, she made herself slam doors shut in her mind. She could be afraid later, when it was over.

The two galleys accompanying the caravel were aware of the disaster by now. Their aghast crews rowed closer to attempt rescue of any survivors, for no one doubted the vessel must sink. Even a massive greatship could go to the bottom in no more time than it took to turn a half-hour glass, once fire took hold of her timbers.

The first galley to reach the caravel stood well off her starboard bow, mindful of the undertow with which a sinking ship dragged down everything around it. The few seamen who noticed the waiting galley made no effort to signal it closer. As long as their commander stood among them, smoke-blackened and fighting, they would not leave her.

A sooty pall stained the sky.

Even under Grania's direction, there was much confusion and wasted motion. One man reeling back from a gout of flame caromed into two more, causing all three to fall across a hatch grating in a tangle of legs and profanity. The fore topsail, ripped too impatiently from its yards, crashed down onto the deck, burying men beneath heavy canvas that immediately began to smolder. In frantic haste those nearby struggled to lift the sail over the side, but one unfortunate fellow got tangled in the rigging and went with it, screaming all the way down to the water.

His voice could not be heard above the din of disaster.

Standing with her back to the mizzenmast, Grania was beating at the fire with a rhythm that had developed a life of its own. Swing the arms, strike down, flap the scorched fabric to clear it of sparks, and lift it again. It was like reefing sail; she could lose herself in the physical act. Just fight and fight, the fire would not get this ship. Not her ship.…

She became aware of someone close beside her, beating the flames with a broom. From the corner of her eye she glimpsed the young apprentice she had saved earlier. The boy gave her a shy grin, a flash of teeth in a smudged face.

Grania's mind slowed, distorting time. Her body continued to function automatically, and she saw her arms lift—ever so slowly— then bring the cloth down as if there were all the time in the world. Time enough to muse on a universe where no ship was burning and no death hung like a raven in the air.

In such a universe, the apprentice had once stared at her with his mouth hanging open and a blush rising up his pimpled neck. Reflected in his dazzled eyes had been an image of embodied myth. Gráinne Ni Mháille as the warrior goddess of Gaelic legend.

She could not help being amused. In her own version of reality, Grania saw herself as a plain woman toughened by need and circumstance. The courage and daring that had already made her famous on the west coast of Ireland were a form of callus, built up layer by layer to shield hidden fears and wounds.

But the apprentice with his worshipful face had demanded she be responsible for his truth and live up to his image.

"What sept are you, lad? What clan?" she shouted to him.

"I am called Fergal, of the line of Owen, clan O Flaherty," he called back, choking on smoke. "From the region of the Twelve Bens," he managed to add, for a man must locate himself by place as well as by blood.

"You are far from home, then," Grania said. Boy with a face and now a name and family, from a place she knew. She would have to see that he got back to the Twelve Bens safely.

A fearful cry rang out. "The fire is belowdecks!" Grania responded with an oath. But at least she and Fergal had made progress; the flames in their area were almost extinguished. Leaving the boy and his broom to finish the job, Grania hurried down the companionway to the lower deck to determine the extent of the fire for herself.

A billow of smoke greeted her, accompanied by the scurrying of rats fleeing from the hold below. Her first mate had followed her; she felt his hand on her arm. "You could be trapped if you go any farther," he warned.

She shook him off. "Come with me then, Tigernan, and be the eyes at my back. I have to see how bad this is, because if the fire eats through the hull we're lost."

"We're lost anyway," he tried to tell her. "The ship's afire from bowsprit to poop."

"Burning, perhaps, but not yet sinking!" Grania snapped at him. "Follow me, and be careful." She headed for the ladder down to the cargo hold.

Tigernan hurried after her naked back, trying without success to overtake her in the cramped spaces belowdecks. He had obeyed her orders in many a rough sea and tried to interpose himself between Grania and many a danger—but as usual, she was too quick for him.

There was heat in the cargo hold, but no flame. If the trading wool they were carrying down there had been burning, Tigernan thought, the stench would have already sickened everyone aboard.

"The fire's still above us," Grania said with relief. "We may yet save her. Go back up, Tigernan, and bring me a party of men to fight the fire wherever we may find it. Hurry!"

Belowdecks was a luridly lit nightmare: hot, suffocating, with air thick enough to swim in and too murky to see through. The fire sped through the ship in thin lines, following the pitch and oakum used for caulking seams. But Grania was right, it had not yet reached the lowest levels; there was a remote possibility they could stop it.

All sense of time was lost. The commander and her crewmen were trapped in a burning box, and the only way out was through. The fire was no sooner extinguished on the gun deck than it was discovered in a companionway, and must be pursued with haste, with prayers, with desperation.

The only way out was through. Through the smoke, through the flames, beat them down, beat them back, the fire must die so humans could live.

They passed the point of exhaustion. Muscle and sinew could give no more, yet somehow they did. Step by step, even to the base of the capstan-shaft, the fire was challenged and defeated.

When Grania at last led her weary but victorious men up from below, devastation greeted them.

The masts stood like charred trees, festooned with black spiderwebs of burned rigging. The fire had reached as far as the forecastle, and smoldering sea chests were still being tossed overboard by men too tired to try to salvage their contents. The ship's boat had also gone overboard, blazing down into the sea with a shaft of steam to mark its passage. The seamen who had stayed topside to fight the fire there were scarcely recognizable now, devoid of clothing and singed black. Some lacked hair and eyebrows; everyone was blistered and beginning to feel the pain.

But the caravel was still afloat, and where there had been flame there was only smoke and sizzle.

"Signal the galleys to come alongside and take off the seriously injured," Grania ordered. "Then we'll assess the damage."

The ship was listing badly to port. It was soon apparent she was too burned to be controllable, for without the use of her sails a caravel was helpless. She would have to be towed to the nearest safe harbor if she was to be salvaged at all, and Grania's men were beginning to suggest rather loudly that it would be best if everyone got off the ship.

But their commander refused. "I sailed out with her, I go back with her. You can leave if you like, so long as a skeleton crew remains with me to handle the towing. Tigernan, there was an apprentice— Fergal O Flaherty, from somewhere near Ballinahinch. Find him for me, will you? I want to be certain he is all right."

The galleys pulled alongside and began taking off the injured, men hurrying up a boarding ladder to receive the broken and unconscious as their mates passed them over the rail. Someone brought Grania a mantle. Only then did she realize she was naked above the waist.

She rubbed at her sweated skin with her palm but only succeeded in smearing the greasy soot that clung to her. Shrugging, she threw the cape across her shoulders and pulled it over her breasts. She glanced up and saw a sailor staring at her.

The man quickly looked away again, but not before her laughter singled him out. "Aye, look at me, Ulick McAnnally!" Grania challenged him. "When next you are ashore and someone tells you Gráinne Ni Mháille is really a man, you'll have an answer for them!"

Fergal was brought to her. The boy was coughing incessantly, but his eyes lit up when his commander called him by name. "I'll see you get safely home," Grania assured him, "and when you are well again you have a place on my ship at any time."

He turned away as a spasm wracked him. Grania saw his shoulders flinch from the pain. Perhaps his lungs were seared. The youngster might never be fit to sail again—he might not even live to become a man.

She put her hand on his shoulder and felt how narrow the bones were, how young. She leaned close to him and whispered, for his ears alone, "Everything hurts, Fergal. All the time. Start with that and life won't be able to disappoint you."

She could tell that he did not understand, though he drew his singed eyebrows together in an effort at concentration in spite of his pain. But someday he might recall her words and draw some strength from them. It was little enough to give him for having thrown away his health in her service.

Every muscle and bone in Grania's body ached. When she moved she thought she must creak like the ruined superstructure of her ship. She too was burned and battered. But still afloat. Still afloat. She lifted her chin and surveyed the wreckage around her, already seeing it repaired, the caravel refitted, new paint, clean crisp sails bellying with a following wind…ah, you lovely creature! Then her eyes moved beyond the ship, scanning the far horizon.

She drew in a sharp breath.

Tigernan appeared at her elbow. "We saved her," he said, hardly able to believe it. "Saved a burning ship at sea." He shook his head from side to side, smiling a dazed smile. "There's a lot of damage, some of it below water level, but Magnus and Ruari Oge are preparing to take her in tow with their galleys. There's no harm done that can't be fixed in the shipyard at Kinsale."

"Look, Tigernan," Grania said.

He followed her pointing finger, and the exhilaration drained from him. The bright summer morning was being invaded by a long line of black cloud, racing out of the west. One of the savage Atlantic gales all sailors dreaded was blowing straight toward them. Such a storm was impelled by a wind of irresistible force, capable of capsizing a topheavy galleon in good repair. A burned-out caravel would be swamped by the high seas the wind brought, if not overturned by the first assault of the storm itself.

"We can never outrun that," Grania said bleakly. "And we dare not even attach the tow lines; we would take the galleys down with us."

Coptright © 1986 by Mogan Llywelyn

ISBN 0-765-30838-X

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...