- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

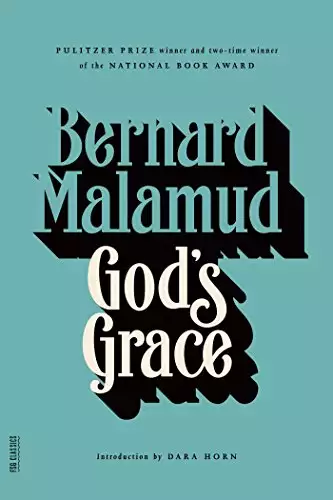

God's Grace (1982), Bernard Malamud's last novel, is a modern-day dystopian fantasy, set in a time after a thermonuclear war prompts a second flood -- a radical departure from Malamud's previous fiction.

The novel's protagonist is paleolosist Calvin Cohn, who had been attending to his work at the bottom of the ocean when the Devastation struck, and who alone survived. This rabbi's son -- a "marginal error" -- finds himself shipwrecked with an experimental chimpanzee capable of speech, to whom he gives the name Buz. Soon other creatures appear on their island-baboons, chimps, five apes, and a lone gorilla. Cohn works hard to make it possible for God to love His creation again, and his hopes increase as he encounters the unknown and the unforeseen in this strange new world.

With God's Grace, Malamud took a great risk, and it paid off. The novel's fresh and pervasive humor, narrative ingenuity, and tragic sense of the human condition make it one of Malamud's most extraordinary books.

"Is he an American Master? Of course. He not only wrote in the American language, he augmented it with fresh plasticity, he shaped our English into startling new configurations." --Cynthia Ozick

Release date: April 15, 2005

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Print pages: 240

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

God's Grace

Bernard Malamud

The Flood

This is that story

The heaving high seas were laden with scum

The dull sky glowed red

Dust and ashes drifted in the wind circling the earth

The burdened seas slanted this way, and that, flooding the scorched land under a daylight moon

A black oily rain rained

No one was there

At the end, after the thermonuclear war between the Djanks and Druzhkies, in consequence of which they had destroyed themselves, and, madly, all other inhabitants of the earth, God spoke through a glowing crack in a bulbous black cloud to Calvin Cohn, the paleologist, who of all men had miraculously survived in a battered oceanography vessel with sails, as the swollen seas tilted this way and that;

Saying this:

""Don't presume on Me a visible face, Mr. Cohn, I am not that kind, but if you can, imagine Me. I regret to say it was through a minuscule error that you escaped destruction.Though mine, it was not a serious one; a serious mistake might have jammed the universe. The cosmos is so conceived that I myself don't know what goes on everywhere. It is not perfection although I, of course, am perfect. That's how I arranged my mind.

""And that you, Mr. Cohn, happen to exist when no one else does, though embarrassing to Me, has nothing to do with your once having studied for the rabbinate, or for that matter, having given it up.

""That was your concern, but I don't want you to conceive any false expectations. Inevitably, my purpose is to rectify the error I conceived.

""I have no wish to torment you, only once more affirm cause and effect. It is no more than a system within a system, yet I depend on it to maintain a certain order. Man, after failing to use to a sufficient purpose his possibilities, and my good will, has destroyed himself; therefore, in truth, so have you.""

Cohn, shivering in his dripping rubber diving suit, complained bitterly:

"After Your first Holocaust You promised no further Floods." "Never again shall there be a Flood to destroy the earth." That was Your Covenant with Noah and all living creatures. Instead, You turned the water on again. Everyone who wasn't consumed in fire is drowned in bitter water, and a Second Flood covers the earth."

God said this: ""All that was pre-Torah. There was no such thing as Holocaust, only cause and effect. But after I had created man I did not know how he would fail Me next, in what manner of violence, corruption, blasphemy, beastliness,sin beyond belief. Thus he defiled himself. I had not foreseen the extent of it.

""The present Devastation, ending in smoke and dust, comes as a consequence of man's self-betrayal. From the beginning, when I gave them the gift of life, they were perversely greedy for death. At last I thought, I will give them death because they are engrossed in evil.

""They have destroyed my handiwork, the conditions of their survival: the sweet air I gave them to breathe; the fresh water I blessed them with, to drink and bathe in; the fertile green earth. They tore apart my ozone, carbonized my oxygen, acidified my refreshing rain. Now they affront my cosmos. How much shall the Lord endure?

""I made man to be free, but his freedom, badly used, destroyed him. In sum, the evil overwhelmed the good. The Second Flood, this that now subsides on the broken earth, they brought on themselves. They had not lived according to the Covenant.

""Therefore I let them do away with themselves. They invented the manner; I turned my head. That you went on living, Mr. Cohn, I regret to say, was no more than a marginal error. Such things may happen.""

"Lord," begged Calvin Cohn, a five-foot-six man in his late thirties, on his wet knees. "It wasn't as though I had a choice. I was at the bottom of the ocean attending to my work when the Devastation struck. Since I am still alive it would only be fair if You let me live. A new fact is a new condition. Though I deeply regret man's insult to a more worthy fate, still I would consider it a favor if You permit me to live."

""That cannot be my intent, Mr. Cohn. My anger has diminished but my patience is not endless. In the past I often forgave them their evil; but I shall not now. No Noah this time, no exceptions, righteous or otherwise. Though it hurts Me to say it, I must slay you; it is just. Yet because of my error, I will grant you time to compose yourself, make your peace. Therefore live quickly--a few deep breaths and go your way. Beyond that lies nothing for you. These are my words.""

"It says in Sanhedrin," Cohn attempted to say, "'He who saves one life, it is as if he saved the world.'" He begged for another such favor.

""Although the world was saved it could not save itself. I will not save it again. I am not a tribal God; I am Master of the Universe. That means more interrelated responsibilities than you can imagine.""

Cohn then asked for a miracle.

""Miracles,"" God answered, ""go only so far. Once you proclaim it, a miracle is limited. Man would need more than a miracle.""

The Lord snapped the crack in the cloud shut. He had been invisible, light from which a voice extruded; no sign of Godcrown, silverbeard, peering eye--the image in which man had sought his own. The bulbous cloud sailed imperiously away, vanishing.

A dark coldness descended. Either the dust had thickened or night had fallen. Calvin Cohn was alone, forlorn. When he raised his head the silence all but cracked his neck.

As he struggled to stand, he lifted his fist at the darkened sky. "God made us who we are."

He danced in a shower of rocks; but that may have been his imagining. Yet those that hit the head hurt.

Cohn fell to his knees, fearing God's wrath. His teeth chattered; he shivered as though touched on the neck by icy fingers. Taking back his angry words, he spoke these: "I am not a secularist although I have doubts. Einstein said God doesn't dice with the universe; if he could believe it maybe I can. I accept Your conditions, but please don't cut my time too short."

The rusty, battered vessel with one broken mast drifted on slanted seas. Of all men only Calvin Cohn lived on, passionate to survive.

Not long after dawn, a faded rainbow appeared in the soiled sky. Although a wedge-shaped section of its arch seemed broken off, as though a triangular mouth had taken a colorful bite, Cohn wept yet rejoiced. It seemed a good sign and he needed one.

The oceanographic vessel Rebekah Q, a renovated iron-hulled, diesel-powered, two-masted schooner, of whose broad-sailed masts one remained erect, drifted unsteadily on the water as the Flood abated--the man-made Flood, Cohn had been instructed, not God-given.

The waters receded. They had risen high enough to overwhelm the remnants of the human race; now were slowly ebbing. He imagined the stricken vessel floating over graveyards of intricate-spired drowned cities--Calcutta, Tokyo; London on the water-swept British island. But he would not be surprised if they (he and the she-boat) were still drifting in the outraged Pacific, under whose angry waves he hadsat in a small deep-sea submersible, observing the sea floor at the instant the ocean flared, and shuddered, and steamed; as nuclear havoc struck, causing a mountainous tidal wave that swallowed and spewed forth the low-lying, rusty-hulled research schooner.

Shortly thereafter Cohn had risen from the sea.

His scientist colleagues--he pictured in particular Dr. Walther Bünder departing hastily with his previously packed suitcase, his Cuban stogie clamped in his teeth--and the officers and crew who administered the ship had, seemingly without grace or goodness, disappeared. Their disregard of Cohn had outraged him, though he now admitted that in leaving him behind they had preserved him.

He had descended to the bottom of the sea twenty minutes before the missiles began to fly at each other; and when he rose from the ocean floor, the instant, totally catastrophic war had ended, and mankind had destroyed itself. The lifeboats and most of the life jackets were gone--a few left strewn on the deck. Cohn found a yellow rubber raft that had been inflated and left as though for him; he therefore forgave them their panic-stricken desertion.

He had dangled in the swaying submersible it seemed for hours after the PERIL light had flashed and the buzzer raucously signaled ASCEND. The little submarine swung in insane sweeping arcs. Its pendulous motion churned his stomach and filled it with terror until he felt the steam-powered winch begin to draw him slowly up, stopping several minutes, then drawing him up.

It was a frightful ascent. He watched thousands of maddened fish banging their blind mouths against his lit window.Cohn snapped off the lamp as the submersible moved up luminously in the watery blackness. When he reached the deck on the surface of the sea, no one appeared to secure the tiny submarine and help him out. He had bobbed around in the frothy waves, trying to escape, hopelessly seasick, before he was able to emerge from the hatch and plop, as he vomited, into the water.

Cohn pulled himself up the metal ladder on the hull of the Rebekah Q. The four lifeboats were gone, their ropes dangling like spaghetti strings. The sky was smeared with ashes and the reflection of flames. The ocean was thick with channels of fish scum and floating animal bodies. When the smell of dead flesh assailed him, Cohn at last knew what had happened. He felt sick horror and a retching contempt of the human race. Dozens of steel missiles had plunged to the bottom of the sea and lay there like smoking turds.

Why he had survived Cohn could not guess. He had no idea how long he might go on. It seemed useless to take a radiation reading. Some had lived after Hiroshima; some had not. What comes will come.

In the communications cabin he read a scribbled message on a warped piece of cardboard. Cohn learned what he already knew: Humanity had done itself in.

The rainbow, he remembered, was God's sign to Noah that He would not pour another deluge on the earth. So much for signs, for Covenants.

Dead souls floated on stagnant seas. The Rebekah Q drifted through shoals of rotting fish, and plowed through blackened seaweed in lakes of sludge.

The oceanographic schooner, its lightning-split mast draped in fallen sails, drifted close to volcanic shores as Cohn slept the heavyhearted sleep of the dead. It sailed away from the soaking land before he woke.

He awoke mourning human being, human existence, all the lives lost. He listed everyone he could remember, and the names of those he did not know whose names he had heard. He mourned civilization, goodness, daring, joy; and all that man had done well.

Cohn was enraged with God Who had destroyed His own dream. The war was man's; the Flood, God's. Cohn heard thunder when he thought of God and sometimes hid.

The sky was old--how often had the earth changed as the same sky looked on? Never had there been so much space in space. He had never been so desolate.

Cohn diligently pasted stamps in albums, recalling nations lost; he pitched darts at a red-and-white target in the games room. He read till his eyes were blobs of glue stuck to words. He listened to records on his father the rabbi's portable phonograph. He kept, so to speak, going.

The boat's engines had ceased throbbing; there was no electricity. It seemed useless to attempt to activate the rusty generator aboard; but there was bottled gas to cook with in the galley.

On good days Cohn told himself stories, saying the Lord would let him live if he spoke the right words. Or lived the right life. But how was that possible without another human life around? Only God and he "contending," Cohn attempting to evade His difficult nature?

(Thunder groaning, Cohn hiding.)

No way of outdoing the Lord Who had invented Himself into being. The God of beginnings; He wanted to begin, therefore had begun. Spontaneous combustion? Beginnings were far up the line from First Causes. Therefore where had God begun?

Who was He? You had to see His face to say in Whose image man had been fashioned; and no one could. Moses, who had come close, saw Him through fog and flame. Or from a cleft in a huge rock where the Lord had placed him. And God, approaching the rock in his own light, covered the cleft with His hand, until He had passed by, then removed His hand and Moses clearly saw the Lord's endless back.

Shall I someday see His face? God seemed to feel the need to talk to men. He needed worship, and even faithless men had hungered to worship Him.

Cohn added up columns of random figures. He began and tore up a notebook journal. He trotted back and forth, for exercise, along the 152-foot deck, hurdling obstacles, the fallen mast, yards of canvas sail, instruments of observation, hauling, drilling; tons of thick ropes covered with seaweed, barnacles, starfish, sea detritus; Cohn, despite his small size and slightly bowed legs, had once been an athlete in Staten Island High School.

The radio was dead. He talked to himself. He missed the human voice.

"What can one expect in this life of desolation ?"

--More life?

"To be alive alone forever ?"

--It takes one rib to make an Eve.

"Do you see yourself as Adam?"

--If the job is open.

Wherever they were it rarely rained. The heavy rains had served, and were gone; the present weather was dry, the flood subsiding; but not Cohn's anger at the destruction God had wrought. Why does human life mean so little to Him? Because He hadn't lived it? If Jesus had, why didn't he tell Him about it? Cohn thought he would bring Them to the bar of justice if he could.

(Terrible thundering; he hid for days.)

Drinking water was short. Part of the storage tankful had leaked into the sea, adding to the ocean water. To the bitter salt sea. Food was plentiful but he ate without appetite.

Cohn, proficient in reading geological and biological time in the microfossilized cores drilled out of the ocean floor, could barely read the visible stars. He did not know how to navigate, and could only guess where in the wet world he was; nor could he steer Rebekah Q, though he diligently studied repair manuals of the ship's machinery and electric system. What difference did steering make if there was no dry place to go? He went where the crippled vessel bore him, wondering whether to swim if it sank.

One tedious, sultry day Cohn thought he was no longer in the Pacific. He couldn't imagine where he was. What shall I do, alone of all men on this devastated earth?

He swore he would live on despite the wrathful God who had let him out on a string and would snap him back on a string.

Once he heard an awesome whirring of wings, and whenCohn gazed up to behold a resplendent angel, he saw a piece of torn blue sky shaped like a shrunken hand.

Cohn prayed on his knees. No voice spoke. No wind blew.

One moonlit night, Calvin Cohn, shivering in his sleep, sensed a presence aboard, surely not himself. He sat up thinking of his dead young wife. She had been driving, not Cohn. He mourned her among those he mourned.

He feared that God, in His butcher's hat, was about to knock on the door. For the ultimate reason: ""Kiddo, it's time,"" or hinting, perhaps, to prepare Cohn? He was to be slain, God had said, though not executed. Why, therefore, hadn't it happened in his sleep rather than out of it? You go to bed and wake up dead. Or was Cohn making much of nothing real, letting fear touch his throat?

Or was this sense of another presence no more than anticipation of the land in the abated floodwaters; dove bearing in its beak a twig of olive leaf? Or raven croaking, "Land ahoy! Get your pants on"?

Cohn stared out the porthole glass; moonlight flowing on the night-calm smooth sea. No other sight.

Before reclining in his berth he drew on his green-and-blue striped sneakers and, taking along his flashlight, peeked into each cabin and lab room below the foredeck. There were creakings and crackings as he prowled from one damp room to another; but no visitors or visitations.

He woke at the sound of a whimper, switched on his torch, and strained to hear.

Cohn imagined it might be some broken thing creakily swaying back and forth in the night breeze, but it sounded like a mewling baby nearby. There had been none such aboard, nor baby's mother.

Holding a lit candle in his hand, Cohn laid his ear against each cabin door. Might it be a cat? He hadn't encountered one on the boat. Was it, then, no more than a cry in a dream?

As he was standing in his cabin, a scream in the distance shook him. Bird screeching at ship approaching shore? Impossible--there were no living birds. In Genesis, God, at the time of the First Flood, had destroyed every living thing, had burned, drowned, or starved them, except those spared on the Ark. Yet if Cohn was alive so might a single bird or mouse be.

In the morning he posted a message on the bulletin board in the games room. "Whoever you may be, kindly contact Calvin Cohn in A-11. No harm will befall you."

Afterwards, he heated up a pot of water on the gas stove and then and there gave up shaving. All supplies were short. Cohn piped out the fresh water that remained in the leaky storage tank he had unsuccessfully soldered, and let it pour into a wooden barrel he had found in the scullery. By nightfall almost an eighth of the water in the barrel was gone. That was no bird.

Who would have drunk it? Cohn feared the question as much as any response. He nailed three boards over the head of the barrel. When he wanted to drink he pried one up, then nailed it down again.

He was edgy in the galley as he scrambled a panful ofpowdered eggs that evening before dark, sensing he was being watched. A human eye? Cohn's skin crawled. But he had been informed by an Unimpeachable Source that he was the one man left in the world, so he persuaded himself to be calm. Cohn ate his eggs with a stale bun, washing the food down with sips of water. He was reflecting on the pleasures of a cigarette when he wondered if he had detected a slight movement of the cabinet door under the galley double-sink.

Who would that be?

The question frightened him. Cohn looked around for a cleaver and settled on a long cooking fork hanging on the wall. Holding the instrument poised like a dagger, he strode forward and pulled open the metal door.

The shriek of an animal sent his heart into flight. Cohn considered pursuing it in space but took an impulsive look inside the under-sink cabinet and could not believe what he beheld--a small chimpanzee with glowing, frightened eyes, sitting scrunched up amid bottles of cleaning fluid, grinning sickly as he clucked hoo-hoos. He wore a frayed cheesecloth compress around his neck.

"Who are you?" Cohn cried, moved by his question--that he was asking it of another living being. A live chimp-child, second small error by God Himself? The Universal Machine, off by a split cosmi-second, allows a young ape also to survive?

That being so, the realm of possibility had expanded. Cohn's mood improved. He felt more the old Cohn.

The chimp, swatting aside the cooking fork, bolted out of the cabinet, scampering forward on all fours to a swing-doorthat wouldn't budge. Scooting behind a tin-top work table, he climbed up a wall of shelves and sat perched at the top, persistently hooting. The chimp chattered like an auctioneer encouraging bids as he awaited Cohn's next move. At the same time he seemed to be eloquently orating: he had his rights, let him be.

Cohn kept his distance. He guessed the chimp had belonged to Dr. Walther Bünder, had heard the scientist kept one in his cabin; but Cohn had never seen the animal and forgot it existed. He had heard the doctor walked it on the deck late at night, and the little chimp peed in the ocean.

The ape on the shelf seemed to be signaling something--he tapped his toothy mouth with his fingers. The message was clear--Cohn offered him what was left of his own glass of water. Accepting it, the chimp drank hungrily. He wiped the inside of the glass with his long finger and sucked the juice before tossing the tumbler to Cohn. Hooting for attention, he tapped his mouth again, but Cohn advised him no more water till bedtime.

They were communicating!

Sitting on a kitchen stool, Calvin Cohn carefully observed the young chimpanzee, who guardedly returned his observation. He gave the impression that he was not above serious reflection, a quite intelligent animal. Descending the shelves, he self-consciously knuckle-walked toward Cohn, nervously chattering as the other sat motionless watching him.

Then the little animal mounted Cohn's lap and attempted to suckle him through his T-shirt, but he, embarrassed, fended him off. "Behave yourself." The chimp sat groominghis belly as if he had lived forever on Cohn's lap and punctually paid the rent.

He was a bowlegged, bright little boy with an expressive, affectionate face, now that his fear of Cohn seemed to have diminished. He weighed about seventy pounds, a large-craniumed creature with big ears, a flat nose, and bony-ridged curious dark eyes. His shaggy coat was brown. He seemed lively, optimistic, objective; did not say all he knew. He sat in Cohn's lap as though signifying he had long ago met, and did not necessarily despise, the human race. When in his exploration of his body hair he came on a tasty morsel, he ate it with interest. One such tidbit he offered Cohn, who respectfully declined.

He, feeling an amicable need to confide in somebody, told the little ape they had both been abandoned on this crippled ship, to an unknown fate.

At that the chimp beat his chest with the fist of one pink-palmed hand, and Cohn wondered at the response; protest, mourning--both? Whatever he meant meant meaning, comprehension. The thought of cultivating that aptitude in the animal pleased the man.

What would you tell me if you could?

The young chimp's stomach rumbled. Hopping off Cohn's lap, he reached for his hand, and tugging as he knuckle-walked, led him to a cabin in the foredeck, about thirty feet up the passage from Cohn's.

Cohn had cleaned up and dried his own room; this was a soggy mess. Scattered over the floor were pieces of a man's wearing apparel, silk shirts, striped jockey shorts, knee-length black socks, and dozens of blurred typewritten pagesof what might have been a book in progress adhering to the waterlogged green rug. Among the clothes lay several damp notebooks, a damaged microscope, two rusted surgical instruments. Many swollen-paged damp books were strewn over the floor. Cohn, out of respect, placed them in the bookcase shelves, assisted by the chimp, who seemed to like doing what Cohn did. Several of the books dealt with modern and prehistoric apes; one was a fat textbook on the great apes, by Dr. Bünder. The subject of others was paleoichthyology.

As he inspected the framed pictures on the white walls, Cohn came upon a mottled color photograph of Walther Bünder, a round-faced man with a rectilinear view of life. Wearing a hard straw hat, the famous scientist sat in an armchair holding a baby chimp in diapers, recognizably the lad now standing by Cohn's side. In the photograph the baby chimp wore a small silver crucifix on a thin chain around his neck. Cohn wondered what the doctor supposed it meant to the little ape. He then tried peeking under the boy's bandage, but the chimp pushed his hand away. When Cohn was a child his mother wrapped a compress around his neck whenever his tonsils were swollen.

Cohn had talked to Dr. Bünder rarely, because he was not an accessible person. Yet once into conversation he reacted amiably, though he complained how little people had to say to each other. He had been a student of Konrad Lorenz and had written a classic text on the great apes before concerning himself with prehistoric fish. He said he had divorced his wife because she had produced three daughters and never a son. "She did not look to my needs."He argued she was just as responsible as he for the sex-type of their children. And he had not remarried because he did not "in ezzence" trust women. He called himself a natural philosopher.

Cohn "had to say" that he had studied for the rabbinate, but was not moved by his calling--as he was by his father's calling--so he had become instead a paleologist. The doctor offered Cohn a Cuban cigar he had imported from Zurich.

Why the doctor had not taken his little chimp with him at the very end, Cohn couldn't say, unless the chimpanzee had hidden in panic when the alarm bells rang, and could not be located by his master. Or the doctor, out of fear for his own life, had abandoned his little boy.

What's his loss may be my gain, Cohn reflected.

Close by Dr. Bünder's berth stood a barred, wooden holding cage four feet high. In it lay a small, damp Oriental rug and two rusted tin platters. The chimp, as though to demonstrate the good life he had lived, stepped into the cage, swinging the door shut, and then impulsively snapped the lock that had been hanging open on the hasp. A moment later he gazed at Cohn in embarrassed surprise, as though he had, indeed, done something stupid. Seizing the wooden bars with both hands, he fiercely rattled them.

Get me out of here.

"Think first," Cohn advised him.

Cohn went through the doctor's pockets, in his wet garments, but could not find a key to the cage. He pantomimed he would have to break the door in.

The chimp rose upright, displaying; he swaggered fromfoot to foot. It did him no good, so he tried sign language, but Cohn shook his head--he did not comprehend. The animal angrily orated; this was his home and he loved it.

"Either I bang the door in, or you stay there for the rest of your natural life," Cohn told him.

The chimpanzee kicked at the cage and grunted in pain. He held his foot to show where it hurt.

Cohn, for the first time since the Day of Devastation, laughed heartily.

The little chimp chattered as if begging for a fast favor, but Cohn aimed his boot at the locked wooden door and bashed it in.

The chimp, his shaggy hair bristling, charged out of the cage, caught Cohn's right thumb between his canines and bit.

Cohn, responding with a hoarse cry, slapped his face--at once regretting it. But it ended there because, although his thumb bled, he apologized.

The ape presented his rump to Cohn, who instinctively patted it. He seemed to signal he would like to do the same for Cohn, and he presented his right buttock and was touched by the animal. Civilized, Cohn thought.

In one of the damp notebooks whose pages had to be carefully teased apart, the writing barely legible because the purple fountain-pen ink had run--not to speak of the doctor's difficult Gothic script--was his record of the little ape's progress in learning the Ameslan sign language for the deaf. "He knows already all the important signs. He mages egzellent progress." The accent played in Cohn's head ashe read the doctor's words. He could hear him mumbling to himself as he scratched out his sentences.

Calvin Cohn searched for a list of illustrated language signs but could not find them. Trying another soggy notebook, he came across additional entries concerning Dr. Bünder's experiment in teaching the boy to speak with him. On the last page he found a note in the scientist's tormented handwriting to the effect that he was becoming bored with the sign-language exercises, "although Gottlob gobbles it up. I must try something more daring. I think he ist now ready for it. He ist quite a fellow."

Gotllob!

That was the last entry in this notebook, dated a week before the Day of Devastation.

Cohn was not fond of the name Dr. Bünder had hung on the unsuspecting chimp; it did not seem true to type, flapped loose in the breeze. Was he patronizing his boy or attempting to convert him? Leading the ape by his hairy hand to his cabin, Cohn got out his old Pentateuch, his Torah in Hebrew and English which he had recently baked out in the hot sun, flipped open a wrinkled page at random and put his finger on it. He then informed the little chimp that he now had a more fitting name, one that went harmoniously with the self he presented. In other words he was Buz.

Cohn told him that Buz was one of the descendants of Nahor, the brother of Abraham the Patriarch, therefore a name of sterling worth and a more suitable one than the doctor had imposed on him.

To his surprise the chimp seemed to disagree. He reactedin anger, beat his chest, jumped up and down in breathy protest. Buz was obviously temperamental.

But his nature was essentially unspoiled. Since his objections had done him no great good, he moodily yawned and climbed up on the top berth where, after counting his fingers and toes, he fell soundly asleep on his back.

His mouth twitched in sleep and his eye movements indicated he was dreaming. Somebody he was hitting on the head with a rock? Except that his expression was innocent.

Cohn felt they could become fast friends, possibly like brothers.

Who else do I have?

He locked Buz in the doctor's cabin, and let him out in the morning to have breakfast with him in the galley.

Cohn observed that the chimp had done his business in his tin dish in the cage. Clever fellow, he suited himself to circumstance. Afterwards they played hide-and-seek and Cohn swung him in circles by his long skinny arms on the sunny, slightly listing deck. Buz shut his eyes and opened his mouth as he sailed through the air.

Cohn enjoyed playing with him but worried about diminishing food supplies. Canned goods, except for five cases of sardines, twelve of vegetarian baked beans and three of tuna fish, plus two cases of sliced peach halves in heavy syrup, were about gone; but there was plenty of rice and flour in large bins. The frightening thing was the disappearing drinking water. There were only a few gallons in the barrel. Cohn doled it out a tablespoon at a time.

What if they went on drift

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...