- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

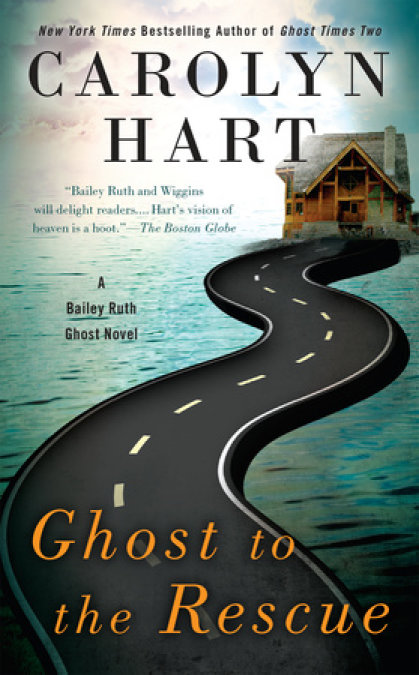

New York Times bestselling author Carolyn Hart's ghostly gumshoe Bailey Ruth Raeburn is frequently amusing…but this is the first time she's been a muse.

Supervisor Wiggins at Heaven's Department of Good Intentions dispatches Bailey Ruth to her old hometown of Adelaide, Oklahoma, to help a single mother and struggling writer. Deidre Davenport is almost broke, supporting two children, and hoping to get a faculty job with the Goddard College English Department. Professor Jay Knox is the one who decides who gets the job, but he's more interested in Deidre's body than her body of work.

Shortly after his advances are rejected, Knox turns up dead-with Deidre's fingerprints found on the murder weapon. Bailey Ruth knows her charge is innocent. Now, she must find out who really knocked off Knox if Deidre and her family are ever going to have a happy ending...

Release date: October 6, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 288

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Ghost to the Rescue

Carolyn Hart

Berkley Prime Crime titles by Carolyn Hart

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 1

Katie Davenport looked up at the stars. Would it make a difference if she asked? After all, she was thirteen, not a little kid anymore, looking up at the night sky and thinking that bright star was listening to her. But still . . . “Star light, star bright, / First star I see tonight, / I wish I may, I wish I might, / Have this wish I wish tonight. Please help my mom.” Katie squeezed her eyes shut. “Star light, star bright . . .”

Paul Wiggins pushed back the stiff cap atop his reddish brown hair. He was a man of his time: thick muttonchop whiskers, a luxuriant walrus mustache, starched high-collared white cotton shirt, heavy flannel trousers supported by suspenders, and a sturdy black leather belt. He turned from the broad window with its commanding view of the rail station platform and silver tracks. A folder rested on the corner of his yellow oak desk. He was rather sure the folder had not been there until this instant.

The folder’s presence reminded him of the power of hopes and wishes that wing their way across starry night skies. He picked up the folder, smiled at a boisterous cover of unicorns, shooting stars, soccer balls, and laptops. He lifted the flap. A dossier contained a photograph of an attractive woman in her mid-thirties with frizzy brown hair and an expressive face. Ah yes, Deirdre Davenport, single mom, struggling author, job seeker. He scanned the facts. Deirdre Davenport was in a tough spot, though not the kind of trouble usually dealt with by members of his department. Still, heartfelt pleas mattered to him. “Star light, star bright . . .”

Slowly, he nodded. He knew the perfect person to send to the rescue.

I welcomed the gentle slap of a swell, quite different from towering waves that crashed over and sank the Serendipity on our ill-fated fishing trip in the Gulf. A steady backstroke carried me through warm salty water toward a beach similar to Padre Island. I took a breath of salt-scented air, then abruptly, as if galvanized, I picked up speed.

I had a sudden bright picture of Wiggins in my mind. Wiggins, the chief of the Department of Good Intentions, dispatched emissaries to earth to aid those in trouble. In my mind, I heard the sounder on his desk amplifying the clack of the Teletype. I reached shallow water and stood. True to my thought, a telegram sprouted in my hand. Breathlessly, I read the message: Your advice and counsel sought. Come at once if possible.

Wiggins is old-fashioned. The fact that telegrams have been supplanted on earth by texts and e-mails is of no interest to him. He sent telegrams when he was a stationmaster in the early nineteen hundreds. He sends telegrams now.

I moved fast, the sudsy, warm water splashing as I went. On the beach my ethereal form appeared in a fetching summer blouse and skirt. No need for towels and such. I simply thought as I wished to be and there I was, red curls shiny as a new copper penny. I waved to gain Bobby Mac’s attention.

He looked across the water and waved in return.

I gestured toward the sky, pulled air deep into my lungs, and managed a creditable imitation of a deep train whistle.

Bobby Mac understood at once, gave me a jaunty farewell salute.

I waved a kiss to my husband. What a man. Bobby Mac is still as dark-haired and handsome as the high school senior who stopped a skinny redheaded sophomore in the hall one day, and said—blunt, forthright, and determined—“We’re going to the prom.” We’ve been going together ever since, good days and bad, happy days and sad. Someday, when we have more time, I’ll tell you the secrets of a happy marriage. Number one? We laughed together. We’re still laughing.

Right now, I had other fish to fry. One of Heaven’s many delights is the ability to go anywhere in an instant. Think, and there you are. I hurried up the steps of a turn-of-the-century redbrick train station. There was no door. As I’ve explained before, Heaven doesn’t run to doors. No one is shut in or shut out.

Heaven?

Do I see an incredulous expression? Hear a cackle of amusement at such naïveté?

It isn’t my role to convince skeptics that Heaven exists, despite my firsthand experience.

Oh yeah? comes a sardonic reply. So who are you and who stamped your ticket to the Pearly Gates?

In a quick thumbnail, I am Bailey Ruth Raeburn, late of Adelaide, Oklahoma. That’s right, late as in dearly departed, though that sounds a little too solemn for me. I prefer happy voyager. That was my attitude on earth as well. As for Bobby Mac, when he wasn’t hunting for oil, he was fishing, and he never met a tarpon he wouldn’t chase. That quest led to our arrival in Heaven when a storm in the Gulf sank the Serendipity. We were on the shady side of fifty when we arrived, but another of Heaven’s delights is the ability to enjoy your very best age. Twenty-seven was a very good year for me, and that’s how I now appear both here and when on earth. I’m a redhead with a spattering of freckles. Green eyes. Slender. Five foot five. A few revelations (not Revelations; that material is more suitable for saints, especially Teresa of Avila, who is as charming as she is erudite; and yes, I do know her. So there!): I love to laugh. I really, really try to follow the Precepts. (More about that later.) I have a taste for fashion.

Fashion. I’d made a quick choice on the beach. I wanted to look just so for my arrival here. I felt like June, the month of daffodils and daisies and dandelions. Yes, dandelions. I love their delicate toppings of fluff. Those feathery crowns inspired my choice of a gossamer-fine pale blue knit top over a white linen tank and white midcalf cotton pants and white wedgies that added an inch to my height. Admittedly, the colors favor a redhead, but I don’t think it’s vain to wish to appear one’s best.

I hurried inside the station.

Wiggins gazed through the window at silver tracks winding into the sky, his genial countenance thoughtful. A thumb and forefinger tugged at his bristly mustache.

“Wiggins!” I caroled.

He looked around, smiled. “Bailey Ruth. It’s good of you to come.” He glanced at a gaily decorated folder on his desk, then at me, started to speak, stopped.

I sensed he was having second thoughts about his summons. Perhaps my costume was too frivolous. Wiggins admires restraint, i.e., he is fond of plain, unadorned—let me be utterly frank—hideously unattractive clothing as an indication of modesty and docility. As Bobby Mac would agree, perhaps too vehemently, docile has never been in my job description. However, Wiggins clearly must perceive a problem calling for my expertise. If, however, my lovely costume was off-putting, I would—nobly—sacrifice for the cause.

With an inward sigh, I transformed my appearance: a prim dull green cotton blouse, a straight khaki skirt, flat black loafers, my tangled red curls drawn back in a bun. My face is rather thin. I hoped I didn’t look like a redheaded ferret. I felt my nose wriggle. Perhaps I’m too suggestible.

Wiggins’s expression remained thoughtful, preoccupied.

The problem, then, wasn’t my appearance.

I thankfully changed back to my summer choice.

Wiggins glanced again at the folder. “Deirdre Davenport is certainly challenged, but perhaps her situation isn’t serious enough to warrant intervention. But that sweet plea by her daughter touched me.”

I looked at him with great fondness. “You are always kind.”

He endeavored to appear stern. “We can’t be everywhere, solve everything.” He began to pace. “I am torn. My resources are limited. Perhaps I am being foolish.”

I avoided saying, Huh?, that favored reply in senior English when I asked a football player to explain the significance of the corrida in The Sun Also Rises. “You know I will be glad to help.”

And, oh, how ready I was for an earthly adventure, though I kept my mien solemn. Wiggins finds a taste for excitement suspect, but, as I always say, why not have fun along the way? It was a motto that served me well in life. And since. Yet I must be circumspect. Wiggins expects his emissaries to be, if not solemn, certainly serious and always to follow the Precepts.

As if in response to my unspoken thought, he gave me a questioning look. “You are always eager to be of help, but this time can you follow the Precepts?”

Was this my cue? Quickly, I took a breath and sang—I have a strong soprano—in a syncopated beat to a version of “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah.”

PRECEPTS FOR EARTHLY VISITATION

• Avoid public notice.

• Do not consort with other departed spirits.

• Work behind the scenes without making your presence known.

• Become visible only when absolutely necessary.

• Do not succumb to the temptation to confound those who appear to oppose you.

• Make every effort not to alarm earthly creatures.

• Information about Heaven is not yours to impart. Simply smile and say, “Time will tell.”

• Remember always that you are on the earth, not of the earth.

I squashed words together to get everything in, but I managed. If I’d hoped for a smile, I was left high and dry.

Wiggins’s gaze was stern once again. “You must admit you have difficulty with Precepts One, Three, and Four.”

Appearing was a sore point between us. It wasn’t that I intended to flout the Precepts when on earth, but honestly, sometimes you have to be there.

“Wiggins.” I was solemn, straightforward, and almost believable. “You know I never want to appear.”

After a moment, he laughed, a wonderful, deep roar of laughter. “When I believe that . . . But you are the right person if this task should be undertaken. You are always creative.”

I basked, unaccustomed to fulsome praise from Wiggins.

“And the problem”—he sat in his desk chair, picked up the folder—“is in Adelaide.”

Whoops. I felt like a fast filly on the homestretch. Adelaide, nestled in the rolling hills of south central Oklahoma, was my town. I was sure it was June and there would be wildflowers, delicate blue and pale rose, and the smell of freshly turned earth after a rain, and the swoop of hawks against the dusky night sky. I loved returning to Adelaide. Of course, I still nurtured a faint hope that someday Wiggins would send me farther afield: Rome, Nome, Madrid, wherever. It was a great big world and I was ready. Would he ever have the confidence that I could succeed elsewhere? Perhaps if I acquitted myself superbly in this instance—whatever it was—my horizons would widen.

“Adelaide? Of course I’ll help.” I perched on the edge of his desk. “I’m ready.”

“You were an English teacher. Another point in your favor.”

I was transported to a hot classroom—not much was air-conditioned when I taught—and a clutch of restive football players, sitting, of course, in the back row. I could see them now: Jack, better known as Two-Ton, cadaverous Michael, mischievous Reggie. I’d won their hearts with Sydney Carton.

I took a deep breath and declaimed—and you don’t know declamation until you’ve taught English—“‘It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.’”

Wiggins’s face softened. “Redemption. Always beautiful. Always noble.”

We shared an instant of silence in tribute to love’s power to transform.

But his worried frown quickly returned. “Delicacy. Behind the scenes.”

I placed my hand on my heart. “You can count on me. Delicacy.” I broke into a soothing verse of “Delicado.” I’d loved Dinah Shore’s version. The song was after Wiggins’s time, but he listened with a faint flicker of hope in his eyes.

“‘Handle with care,’” he murmured. “Yes, decidedly so. A young mother, desperate for a job, and desperate as well for inspiration. Could you be inspiring?” He looked at me doubtfully.

“Can I be inspiring?” I crossed my legs. “Why, inspiration is part of my nature.” There was the time I inspired a mass walkout from a city council meeting, but perhaps that wasn’t quite what Wiggins had in mind.

He brightened. “To serve as a muse is a high calling though not the usual task set for an emissary. Think of the muses, Calliope, Clio, Euterpe . . .” He rattled off the names of the nine muses. “Keep them in mind.”

The Teletype suddenly clattered. He swung about, grabbed a pad, made hurried notes.

Outside came the deep-throated wail of the Rescue Express nearing the station. The clack of the wheels sounded louder and louder. The acrid smell of coal smoke tickled my nose, elixir to a spirit ready to rumble. I came to my feet, held out my hand. “Quick. I’ll go.”

Wiggins glanced out the window, knew time was short. He pushed up from his chair, strode to the slotted wooden container near the ticket widow, grabbed a red ticket, gave it a stamp.

I ran out the door, ticket in one hand, a sheet of paper with Wiggins’s notes in the other. As I climbed aboard, Wiggins shouted, “She is seeking inspiration . . . her plight is desperate . . . bank account . . . Do your best . . .”

I stood in the swaying vestibule—on my way to Adelaide, on my way to Adelaide—and tried to decipher Wiggins’s back-slanted scrawl: Deirdre Davenport . . . single mother of two . . . bank account almost empty . . . writes clever mysteries . . . hasn’t sold her last two books . . . must have a job . . . applied for a faculty position at Goddard . . . decision to be announced tomorrow. . . .

I settled unseen on the chair by the desk in a modest hotel room. The joints squeaked as the chair swiveled.

A young woman flicked a puzzled look toward the chair, then gave a little shrug. I liked her at once. Probably mid-thirties. Old enough to have lived and learned and lost. Frizzy brown hair needed a trim but was the color of highly polished mahogany. She had an air of leashed vitality, a woman with too many ideas to consider and tasks to accomplish and destinations to seek to think about herself and haircuts. Her long, expressive face puffed in exasperation with a touch of bitterness. She sat cross-legged on a saggy sofa, a laptop balanced on her knees. A cell phone rested on a coffee table.

A young thin voice talked fast. “. . . not started yet?”

Obviously, the phone was in speaker mode.

“Not yet, honey.” Her tone was cheerful, but her expression was forlorn.

“Mom, don’t you need to sell a book pretty soon?” The boy’s voice was high and scared.

“Don’t worry, Joey. I’ve had rough patches before. One of these days I’ll be able to start.”

“Look, Mom, I’ve been thinking about your book. I just finished the new book about Elvis Cole. You know—”

Now her smile was wide. “Robert Crais’s PI.”

“He is so cool.” The young voice was awestruck. “Why don’t you write a book like that?”

“I would if I could, but that’s not the kind of book I write. My readers want lots of fun.”

“Mom”—he sounded solemn—“you used to be happy all the time and you couldn’t wait to get to work, but now—”

Deirdre’s angular face drooped. But her voice was brisk. “Hey, Joey, I’m fine. I’ll start a new book this weekend.”

“You will? That’s great.” His voice lifted in relief. Then, a pause. “Can I come home early? Dad’s girlfriend wears perfume that makes me cough and I heard her making fun of my glasses. Please.”

“Baby, I’d come get you if I could. But I have to stay here this weekend. Try to have fun. Your dad loves you.”

“Yeah.” The boy’s voice sagged. “Sure. Then why’d they go out and leave me here by myself?”

Her lips quivered and I knew she kept her voice bright with an effort. “Joey, you can handle it. Look, I’ll drive down Monday and pick you up.”

“Monday.” It must have sounded long distant to him. “Okay. See you then.”

The call ended.

She came to her feet, face crumpling, hands clenched. She took one deep breath, another, another. “Come on, Deirdre. You told Joey to handle it. You handle it. You don’t have any choice.”

I liked the sound of her name, Deer-druh. I liked the way she lifted her chin. I liked her staccato speech.

She clapped her hands on her hips, stared across the room at her image in the mirror. “Handle it, babe. So you owe money everywhere in town. So you spent next month’s house payment to send Katie to camp. So you haven’t sold your last two books and you’ve got two hundred and forty dollars in your checking account and you’re maxed out on two credit cards. Think positively. That’s what you tell the kids. Jay will pick you for the job. Jay will pick you for the job.”

She whirled, flung herself onto the sofa, grabbed the laptop, glared at it. “You’re about as cold as the grave scene in Doctor Zhivago. I told Joey I’d start a book this weekend. Sure, and in my spare time I’ll pop a plan for world peace and write a treatise on the mating habits of piranhas. I try to write and nothing happens. Is it crazy to talk to yourself? But there’s nobody else I can talk to. Wesley likes being single and he has a girlfriend with too much perfume. I can’t tell Joey and Katie that I’m broke and desperate, but they know I’m stressed. It’s like I have coyotes running circles in my head. Bills, Jay, the kids, whether I make the cut, get the job. I can hear Jay now, his voice smooth as honey: ‘My decision is momentous for our faculty, our students, the state’s writing community.’ Oh yeah, pompous ass. Momentous for me and Harry, too. Trust Jay to insist that he’s still struggling with his choice. Too bad he’s got carte blanche. Maybe nobody else on the faculty cares.”

She looked down at the laptop, her face creased in a tight, frustrated frown.

Without warning, the door swung in. A man stepped inside, closed the door firmly behind him. Six feet tall, he was well built, knew it. His T-shirt was tight. Faded jeans hung low on his hips. He was barefoot. He leaned back against the door with all the assurance of a tousle-haired Hollywood bad boy and that was the look on his face—suggestively seductive brown eyes, lips parted in a sleepy smile. “Hey, Deirdre.” He carried two champagne glasses and a magnum. “Time for a little celebration.” His dark eyes ignored her face, grazed slowly down her body, lingered on her long bare legs. “Nice.”

She came to her feet, stood quite stiff and still. “How did you get in?”

“The kid at the front desk doesn’t know who’s in room 206. I told him I was Jay Knox”—emphasis on his last name—“and I locked myself out. So here I am. And here you are.” He drawled the last sentence.

“The clerk should have asked for an ID.” My tone was hot. I clapped a hand over my lips, but it was too late. My husky voice could always be heard in the last row.

He gave her a sleepy smile. “I like the new voice. Deeper than usual. Kind of throaty. Sexy. As for ID, I may have mentioned my uncle. Useful that he owns this place.” He spoke with easy assurance, accustomed to the deference a small town accords certain families.

Knox? Like pieces slotting into a puzzle, I remembered Jeremiah Knox, the long-ago beloved dean of arts and sciences at Goddard. His wife, Jenny, was a volunteer for children, reading, the arts. Whatever needed to be done, Jenny Knox was ready to help. I had a hazy memory they’d had several children. This would be a grandson. He was handsome in the Knox manner, sandy-haired, broad face, generous mouth, but there was a hint of dissolution in the curl of those full lips. Even the best oak tree can spawn rotten acorns.

“Yeah, I like that voice. Say something else, Deirdre.”

Deirdre knew she hadn’t spoken. She looked back and forth, turned to glance behind her.

Jay’s laugh was easy. “It’s okay, sweetie. Nobody here but you and me. I like it that way.” He started toward her.

She said sharply, “Jay, I’m not dressed—”

Actually, Deirdre was more fully dressed than women today appear at swimming pools, and was quite attractive in an azalea pink cotton sateen shirt tunic and adorable light feathery mukluks. Of course, the tunic only reached her upper thighs, and she had long, well-shaped legs.

“—and you need to leave.” Her tone was flat, her gaze cold.

“Less is more.” He placed the champagne bottle and glasses on the coffee table in front of the sofa, but he never took his eyes off of her. He took one step, another. She stood her ground. “Jay, I’m asking you to leave. Now.”

He reached her, stood too close. “Come on, Deirdre. You’re no kid. The night’s young. We can have fun.” He reached out with both hands, gripped her arms, pulling her close.

“Let go.” Deirdre’s voice rose.

He gave a hot, low laugh. “Loosen up, lady. Maybe I forgot to mention all the duties in your job description. That is, if you get the job. How bad do you want the job, Deirdre?”

She strained backward. “Let me go.”

I was at the door. I yanked it open as, colors swirling, I appeared—but, of course, I was already inside the room.

Jay stood with his back to me, hands clamped on Deirdre’s arms.

Deirdre stared past Jay at me. Her eyes widened. Her lips parted. She tried to speak but no words came.

I looked over my shoulder as if speaking to someone in the hall. “I’ll take a rain check on a drink. I promised Deirdre I’d drop by. She offered to help me”—I was at a momentary loss, but after all, as Wiggins recalled, I had taught high school English—“with the transition from chapter four to five. She’s so generous to new writers.” By the time I closed the door and moved toward Deirdre and Jay, he was standing a few feet away, facing me, a startled look on his face.

“Professor Knox,” I burbled as I hurried forward, gazing at Jay in delight. “I’ve heard so much about you.” This was usually safe, though I knew only enough about him to write a single-word description: Jerk.

Deirdre blinked several times, perhaps trying to erase the memory of colors moving and coalescing.

I glanced at the mirror. Surely she approved of my ivory cotton-knit tunic with the most elegant medallion trim at the neckline and six to eight inches of an intricate design at the hem. Black leggings and black strap sandals with faux stones were a perfect foil for the ivory. And, of course, for red hair.

I held out my hand to Jay, loved the flash from the large faux ruby ring that echoed the red stones on the sandals. “I’m”—I hesitated for an instant. St. Jude was the patron of impossible dilemmas, and that seemed a good appraisal of Deirdre’s status—“Judy Hope.” Surely Wiggins would be impressed.

I glanced at Deirdre.

Her expression was glazed, but she came through. “Judy”—she managed a strained smile—“I’m glad you were able to . . . drop by.” She was torn between sincere gratitude for her deliverance and mind-stretching incredulity at my arrival.

“I’m so eager to talk about the transition.” I hoped this would help her get past her wooden speech.

“Transition,” she repeated as if the word had no meaning, her gaze still focused on me. “Oh. Oh yes, of course. Transition! We had a good discussion about leading into a new chapter. I know we can make some progress.” She turned to Jay. “I know you’ll forgive Judy and me if we get right to work.” She hurried to the coffee table, grabbed the champagne bottle by the neck and the glasses in her other hand, thrust them at him. “I’ll see you in the morning.”

He took the bottle, tucked it under his arm, the glasses in his left hand. He moved in an easy slouch, gave her a steady stare when he reached the door. “Tonight. Cabin five.” He spoke casually, but the message in his eyes was clear: You want the job? Show up.

Chapter 2

I’d like to say Deirdre was delighted when the door closed behind him.

Instead, she stared at me and slowly backed away, a step at a time. “You . . . weren’t there.” Her voice was shaky. “The doorway was empty. Nothing. And then”—she waved her hands—“colors shimmered. There you were. You can’t be here, but you are. I see you. I must be crazy.” She clasped long slender fingers to each temple.

“You’re not crazy at all. I wasn’t there. Then I was.” I was glad to reassure her.

She gave a ragged laugh. “That’s swell. Not there. Then here.” She stumbled to the sofa, sank down in one corner. “It’s stress. I’m trying to come up with a book. Maybe you’re part of a book.” There was a desperate hope in her voice. “Yes. A book. There’s this cute redhead—”

I smiled. What a dear girl.

“—who is Johnny-on-the-spot when Jay’s acting like an ass.” She stopped, looked grim. “It was worse than that. I’m afraid if you hadn’t come . . . But you did. Look, did you ask for a key at the desk and maybe the light was funny when you came in . . . ?” Her words straggled to an end.

“It’s better not to worry about things we can’t change.”

I saw the realization in her eyes that the light in the doorway had been fine. She’d seen colors and the colors were me appearing and that was not an experience she understood.

I was brisk. “Everything works out for the best. I was able to come and intervene in what had the makings of an unfortunate event.”

“Very unfortunate.” Her voice was thin. She gave me a long, careful look.

I resisted fluffing my hair. A quick glance in the mirror reassured me. I looked as nice as could be.

“Judy Hope,” she said experimentally. “You aren’t wearing a name tag.”

“Should I be?” I was truly curious.

“Are you here for the writers’ conference?”

I beamed at her. “I’m here for you. I want to help you with your stress. What’s the problem?”

She squeezed her eyes shut for a moment, opened them.

I smiled again.

Her breath was a little quick. “Judy Hope. Okay. As they say, when somebody gives you a gift, say thank you, even if you don’t have a clue about why. Thank you. You arrived in time to save me from a fate I wouldn’t wish on any job seeker—”

“Job seeker?”

“If you’re here to help me, you missed out on the basics. Problem? I guess I can sum it up in two words. Money and sex. I need a job. Specifically, I applied for a new opening in the English Department at Goddard. . . .” She looked at me questioningly.

“Goddard College, the pride of Adelaide.”

“Okay. Anyway, itR

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...