- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

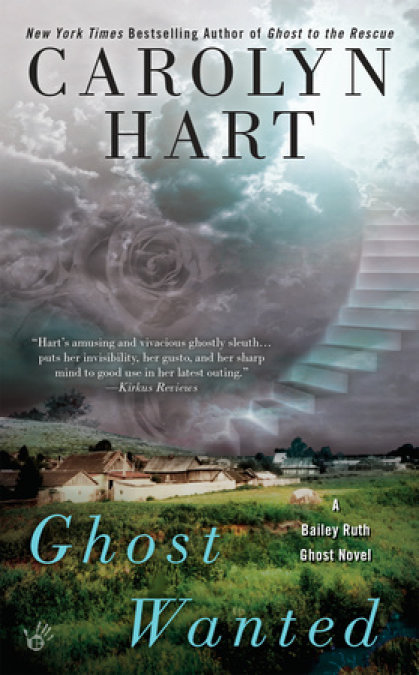

New York Times bestselling author Carolyn Hart treats readers to another visitation by ghostly gumshoe Bailey Ruth Raeburn as she lends a hand to an ethereal matchmaker who haunts a library...

Bailey Ruth's supervisor, Wiggins, is worried about a dear old friend-the ghost of elegant Lorraine Marlow, who haunts Adelaide, Oklahoma's college library. Known as the Lady of the Roses, she plays matchmaker, using the fragrant flowers to pair up students. But someone's making mischief after hours, leaving roses strewn about the library and stealing a valuable book. Concerned with Lorraine's reputation among the living, Wiggins dispatches Bailey Ruth to investigate.

Soon trouble begins to stack up. A campus security guard is shot by an intruder, and Bailey Ruth uncovers a catalog of evidence blaming a student for the crimes. But something isn't adding up, so with police preparing to make an arrest, the spirited detective must find the real culprit. Because when justice is overdue, it takes more than death to stop Bailey Ruth Raeburn...

Release date: October 7, 2014

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Ghost Wanted

Carolyn Hart

Chapter 1

Bobby Mac and I don’t spend every moment aboard our cabin cruiser, Serendipity, on jade green waters reminiscent of the Gulf. Heaven knows that where you wish to go, there you are. It might surprise you that a rough-and-tumble oilman like Bobby Mac knew his way around art museums on earth. His tastes—and mine—were eclectic, from Gustav Vigeland’s sculptures to Mary Cassatt’s Breakfast in Bed. It was Heavenly now to see one of our favorite artists at work. Sunlight-dappled water lilies in the pond. Bobby Mac and I stretched on a blanket, quiet as stone cherubs, watching Claude at work on a new painting.

A telegram sprouted in my hand. My eyes widened. I will admit to a thrill of excitement. I waggled the stiff yellow sheet at Bobby Mac. He gave me a thumbs-up, as he always does. What a guy. We met in high school when he was a dark-haired, muscular senior and I was a skinny redheaded sophomore. We’ve been having fun ever since.

I blew Bobby Mac a kiss and went at once to the Department of Good Intentions, arriving immediately. That’s the beauty of Heaven—here can immediately be there. It’s all in the spirit.

Oh dear, you are already puzzled. Bobby Mac? Sunlight-dappled pond? Do I mean Giverny? Claude? Telegram? From there to here in a heartbeat?

Perhaps I should begin with me. I am Bailey Ruth Raeburn, late of Adelaide, Oklahoma. Yes, late. As in dear departed. Dear departed has a lovely ring, though I’d be the first to agree that not everyone in Adelaide had adored me. There was the high school principal who hadn’t been pleased when I flunked the coach’s son. All endings lead to new beginnings, and I loved my years as the secretary at the Chamber of Commerce, which provided a front-row center seat for both public and private shenanigans. There was the time . . . Oh, sorry. I am easily distracted.

Back to my departing . . . Bobby Mac Raeburn, the captain of my heart and of the Serendipity, steered us out into the Gulf of Mexico seeking a recalcitrant tarpon despite lowering clouds and a whipping wind on what would be a fateful day. For us. Suffice to say, after a valiant battle with the elements, the Serendipity was lost in the Gulf and Bobby Mac and I arrived in Heaven. Now the Serendipity, as bright and fresh as on the day she was launched, rocks in a tranquil Heavenly sea and provides a haven for me and Bobby Mac.

Those who dismiss the idea of Heaven as balderdash will flee from my narrative. Isn’t balderdash a lovely word?

I am in good company—of course, given my current location, that surely goes without saying—in choosing balderdash. No less than Thomas Babington Macaulay, the great nineteenth-century historian, once said, “I am almost ashamed to quote such nauseous balderdash.”

Heaven is no more balderdash than I. However, to convince the skeptic is not my task at the moment. I remain confident that there is, however feeble, a spark of yearning within each earthly soul for all that is holy.

Don’t be put off by a mention of holiness. Heaven isn’t solemn. You enjoy laughter? Holiness does not preclude humor. Saint Teresa of Ávila combined a deep sense of ineffability with a laughing heart. As she once said, “Lord, if this is the way you treat your friends, it’s no wonder that you have so few!” Laughter is always to be found. Just the other star-spangled night, Bobby Mac and I loved every minute of Danny Thomas’s new special, and Saint Jude was in the first row, cheering him on.

Claude Monet? He remains a genial fellow and doesn’t mind at all when admirers gather to watch the progress of another masterpiece.

As for the telegram from Wiggins—more about Wiggins in a moment—the dear fellow remains a man of his times, the early nineteen hundreds. I’m sure if I were associated with an up-to-date department, there would be e-mails and texts galore, but my heart belongs to Wiggins’s delightful Department of Good Intentions, which is housed in an old-fashioned train station, a replica of Wiggins’s earthly train station, where he served as stationmaster.

As for my swift arrival upon receipt of the telegram: There are no barriers in Heaven. From there to here is as quick as a thought. Have a yen for a swoop down a snowy mountain? Even better than Vail and no smashups. Or perhaps your taste runs to bird-watching. All God’s creatures have their place. Yes, all those companions we cherished through the years, tabby cats and Labs for us, are here, as loving as the day they departed earth. Sometimes, if you feel that you have a glimpse of Heaven when you see an eagle on the wing or the ineffable grace of a prowling panther or a swirl of monarch butterflies, you are quite right. All the beauty on earth that makes your breath catch and eyes mist is only a foretaste of Heavenly extravagance with color and motion and being. Just this morning I saw an Eastern Rosella, gloriously red and white and gold with touches of green and blue. Look them up the next time you’re in Australia.

I paused to admire Wiggins’s redbrick country station with its wooden platform. Shining silver tracks stretched into the sky. Immediately I was eager to swing aboard the Rescue Express, the train Wiggins dispatches to earth with emissaries to help those in trouble.

I paused near a crystal arch outside the station to gather my thoughts and consider my appearance. The telegram—I fished it from my pocket—seemed somewhat overwrought for steady, resolute Wiggins. I read it again: Bailey Ruth, Dastardly deeds in Adelaide. Come at once. Posthaste. Wiggins urged quiet, behind-the-scenes action by the department’s emissaries. After returning from my last jaunt to earth, he had said rather plaintively, “Becoming visible always leads to complications.” Yet surely my summons meant he appreciated my willingness to assess a situation and do what needed to be done, even if I broke a few rules along the way.

Wiggins is devoted to rules, i.e., the Precepts for Earthly Visitation. I know them now by heart and have no need to carry with me a roll of yellowed parchment with elegant inscriptions. I can recite the Precepts quickly if asked.

I cleared my throat, took a deep breath. I spoke clearly. With resonance. Any former English teacher can always be heard from the last row.

PRECEPTS FOR EARTHLY VISITATION

1. Avoid public notice.

2. Do not consort with other departed spirits.

3. Work behind the scenes without making your presence known.

4. Become visible only when absolutely necessary.

5. Do not succumb to the temptation to confound those who appear to oppose you.

6. Make every effort not to alarm earthly creatures.

7. Information about Heaven is not yours to impart. Simply smile and say, “Time will tell.”

8. Remember always that you are on the earth, not of the earth.

A prefect rendition, if I did think so myself. If I had a moment, I would no doubt delight Wiggins by enunciating each and every Precept. The Precepts were now ingrained in my inner being. That is possibly an exaggeration. Truth to tell, and that is a Heavenly requirement, I often fail to adhere to the Precepts, which makes Wiggins doubt that I am qualified to be a Heavenly emissary. I know Wiggins never questions my intentions. As he’s often told me, “Bailey Ruth, you mean well, but . . .”

I hoped he understood that I not only had the best of intentions, I was admirably serious and devout.

Scratch the last.

I can’t claim saintliness.

Didn’t that better equip me to help those still on earth? Level playing field and all that, one imperfect being aiding another. Though of course, once in Heaven . . . Ah, but I mustn’t violate Precept Seven. I offer my fragmentary descriptions of Heaven only to establish my identity.

In a moment of self-appraisal, I also scratched serious. Unless we were speaking of having a seriously good time. All right, I couldn’t present myself as serious or devout, but I could always cling to good intentions. With that reassurance, I was ready to pop inside the station; then I paused.

Wiggins was not au courant with fashion. I considered my attire, a fetching white linen suit with faint narrow charcoal pinstripes. White is always flattering to redheads. Had I mentioned that I have flaming red hair, curious green eyes, and a spattering of freckles on my face? My age? Well, let’s say I was on the shady side of fifty when the Serendipity went down, but in Heaven you are what you want to be. Twenty-seven was a very happy year for me, so that’s the Bailey Ruth you see. However, perhaps my white suit and white strap sandals were too stylish. I wasn’t as fine as an Eastern Rosella but satisfactory, assuredly satisfactory.

I glanced at my reflection in the crystal.

Flamboyant?

I do not, Heaven forbid, spend time dwelling on how I look.

Well, not much time.

Perhaps I should appear a trifle dowdy when I met with Wiggins, as a counterbalance to shiny flyaway red curls and bright green eyes and bubbly effervescence. I can be restrained. Yes, I can. As for my costume, I’m afraid Wiggins sees pleasure in gorgeous clothing as evidence of intrinsic frivolity. What is life without an appreciation of beauty?

This was not the moment to reinforce his view of me as well-meaning but prone to flouting regulations with wholesale abandon, not with a telegram clutched in my hand. I sighed as my reflection in the crystal swirled from loose red tresses—think Maureen O’Hara—and crisp linen suit to hair drawn back severely in a knot, an undistinguished tan blouse, and, painful though it was, brown twill trousers. I gritted my teeth, added brown ankle boots. I was suffused with a sense of nobility at my sacrifice for the cause.

I hurried toward the station steps, remembering my shy arrival when I’d first come to the Department of Good Intentions to volunteer. At least now I knew I was welcome. A tiny doubt flowered. Wiggins was a welcoming man, but that last adventure—well, surely he knew I’d done the best I could despite huge challenges. It wasn’t my fault that I appeared, and there I was, unable to disappear. But that’s another story.

I was reassured when Wiggins burst through the open doorway. The lack of doors is another lovely aspect of Heaven. All may enter and depart without hindrance.

I beamed at him. “Wiggins, I came at once.”

Wiggins looked just as I’d seen him on my initial visit to the Department of Good Intentions—thick, curly reddish brown hair; genial, broad face beneath a green eyeshade; robust walrus mustache; stiffly starched white shirt with sleeves puffed from black arm garters; heavy black woolen trousers held up by wide suspenders in addition to a broad leather belt; high-top black leather shoes buffed to a gleaming shine.

His first words destroyed any illusion of Wiggins as usual. “Bailey Ruth”—his voice was near despair, his spaniel-sweet brown eyes beseeching—“you’re living proof that appearances can be deceiving.”

I stared in surprise. Had my brown wren ensemble shocked him? Did he instead prefer the more au naturel Bailey Ruth, red curls bouncy, new fashions on display? Happily, I swirled back into my white linen suit with the faint charcoal gray stripes that added cosmopolitan flair and the cunning white sandals. I fluffed my liberated hair.

He stared in return, but I realized he didn’t see me. His eyes looked through me. There was anguish in their brown depths.

I came nearer, touched his arm. My fingers traced through the ethereal Wiggins, yet I sensed a spirit tensed against pain. “Tell me, Wiggins.”

“I shall. I must.” He inclined his head, then, ever the gentleman, stood aside for me to precede him. I led the way to his office. I waited until he settled behind his golden oak desk in a bay window that afforded an excellent view of the waiting room and the station platform and silver tracks winding away into the sky.

He clasped his strong hands together. Words came in disjointed bursts. “. . . disgracing her name . . . can’t abide this . . . although I shouldn’t intervene . . . her choice not to come yet . . . thought she wanted to stay near Charles . . . but he’s here now. . . .” He looked perplexed, then said firmly, “Of course, there’s no time in Heaven. Passage of earthly time is of no importance. Except, of course”—his tone was kind—“to those on earth. I understood she wasn’t ready to come for some reason.” He tugged at one side of his walrus mustache. “She’s brought much happiness these past years. To see the legend of the Rose Lady forever linked to ugliness would break my heart. I know no one can—or should—believe her spirit is behind the occurrences this week, but there is a deliberate effort to connect Lorraine’s roses with vandalism and theft. Yet how can I justify a mission to protect her reputation when there are many people in truly dire straits?” He was clearly in misery.

To say I was bewildered put it mildly, though clearly Wiggins was despondent because someone he cared about was in a pickle. I grappled with the fact that time seemed paramount to him. “No time in Heaven. Certainly not, Wiggins.” I made a huge effort to appear comfortably knowledgeable. Of course there was no time in Heaven. Everyone knew that. Right, and maybe everyone but me understood the concept. In my defense, I never understood how those little pictures got in our TV set when I was on earth. I turned on the TV and there was Lucy. Click a switch and the lightbulb burned. These things happened. Did I need to understand the physics of the phenomena? I am similarly ill equipped to explain the relationship between Heaven and Time. However, the matter seemed of great import to Wiggins. I made soothing noises. “Certainly, Wiggins. Absolutely understandable. No time in Heaven. Absolutely not.”

His glance was pathetically grateful. “You grasp the point. There are those who are drawn to remain and do good. But now . . .” His golden brown eyes filled with dismay. His mustache quivered. “Surely she will see that she must finally depart earth. I can’t approach her directly. I wish I could.” The yearning in his voice touched me. “To speak with her . . . But that would never do. What I need is tact. Empathy. Behind-the-scenes”—sharp emphasis—“exploration to discover the miscreant, bring an end to this dreadful exploitation of her good name.”

Behind the scenes. I was hearty, as if there could be no doubt that I, of all emissaries, would remain behind the scenes. Wiggins has a horror of his emissaries appearing on earth. Regrettably, in the past, I sometimes felt forced to appear. “You can count on me. Behind the scenes.” I admired my resolute tone.

It would be nice to say my words reassured him. Nice, but inaccurate. In fact, he sighed.

“Wiggins, I always try to do the right thing.” I might have sounded a little defensive.

He looked stressed. “If it weren’t Adelaide, I wouldn’t have summoned you.”

Adelaide was my home when I was alive, a lovely small town in the rolling hill country of south-central Oklahoma. Although there is no time in Heaven, I’d been pleased on my return visits there to see what the passage of earthly time had wrought in Adelaide in the years since the Serendipity went down. Adelaide was prosperous, growing, vibrant, thanks in large part to the accomplishments of the Chickasaw Nation.

I’d now completed four successful adventures in Adelaide on behalf of the department. Scratch that. Four missions. Wiggins abhors the idea of ghosts having adventures. Oh, there I go again. He also abhors the use of the term ghost. He equates the noun with the popular picture of ghosts as scary creatures rattling chains. Why chains, I wonder? In any event, I don’t see that saying tomahto makes the fruit any different than tomayto. Emissaries are invisible visitants (except when circumstances arise, as I have indicated) from Heaven to earth. If that doesn’t mean ghosts, I wasn’t standing here in a white linen suit with a delicate gray stripe. As for his stricture against equating a mission with adventure, I firmly believe adventures are good for the spirit. Especially mine.

“Adelaide.” I beamed at him. “Wiggins, you know I can help.”

Dot. Dot. Dot.

True to the early nineteen hundreds, the latest intelligence reaches Wiggins via Teletype.

Dot. Dot. Dot.

He whirled at the urgent sound and rushed to the telegraph key fastened to the right side of his desk. A sounder amplified the incoming messages.

Wiggins dropped into his chair, made rapid notes, his face creased in concentration. Once he drew a sharp breath. The clacks ended. He swung in his chair to me. “You know Adelaide. You could help her.” But he sounded anguished. Clearly he was conflicted. “Precept Two. I have always insisted that Precept Two be observed.”

Dot. Dot. Dot.

“Oh, Heavens.” Wiggins took a deep breath and gazed at me with a mixture of hope and shamefacedness.

Shamefacedness? Wiggins? Whatever could be upsetting him? I hastened to help. “Precept Two,” I repeated firmly. I knew the Precept, of course: “No consorting with other departed spirits.” “Wiggins, don’t worry. That’s the last thing I’d do.” I hoped, of course, he was too distracted to remember that was exactly what I’d done on my last visit to Adelaide.

Wiggins didn’t appear consoled. If possible, his expression grew even more doleful. “Right.” His tone was hollow. “Absolutely. Definitely, you must observe Precept Two.” He appeared completely demoralized.

Clack. Clack. Clack.

He gave the sounder a desperate look, bounded to his feet, and dashed to the ticket box. He pulled down a bright red ticket, stamped the back, and thrust the ticket toward me. “Go. Try. Do what you can. She—oh, Bailey Ruth, she needs help.”

She? In the past, when Wiggins briefed me on a mission, he explained who I was to help. Last time was an exception, of course. But now as I grabbed my ticket, I knew only that she was in trouble. There was no time for more, because the rumble of iron wheels on the silver track was deafening.

I rushed out to the platform as the Rescue Express thundered on the rails. The train paused long enough for me to swing aboard a passenger car. I stood in the vestibule, held tight to a hand bar, and leaned out as the Express picked up speed.

Wiggins’s frantic shout followed me. “Dark dealings being blamed on her. Her portrait . . .” His words were lost in the rumble of the clacking wheels.

Chapter 2

I stood in darkness on a wide central landing of wooden stairs. To my right and left, flights led from the landing to the next floor. Golden-globe wall sconces shone at the top of the upper stairways and at the bottom of the central steps. I sensed without seeing much of my surroundings that I was in an old building. Years of use had hollowed the wooden treads. The wooden railings were ornately carved. Should I go up? Left or right? Or possibly down? Wiggins had sent me in such a rush. . . .

Brisk footsteps sounded below.

I looked over the handrail.

A flashlight bobbed. I dimly saw a stocky shape behind the beam. There was no attempt at concealment. Footsteps thumped loudly on the wooden treads.

I was careful to stay out of the way when he reached the central landing. It startles earthly creatures if they bump into an emissary. The concept of an invisible entity with substance may be as puzzling to the reader as my difficulty with time and Heaven. Take my advice—don’t trouble yourself trying to understand the inexplicable.

The newcomer stopped on the landing. His arm swung up and the flashlight beam illuminated a portrait in a fine gilt frame. “No problems tonight, Miz Lorraine.” There was a defensive edge to the gruff tone, as if he were making an apology of some sort. “I do my best. I can’t be here and there and everywhere at the same time. I’m sorry as can be I mentioned you to that student reporter. But when there were roses everywhere, I thought maybe you were doing something special. Everybody on campus knows you loved giving out roses. I’m sick about those headlines in the student newspaper—”

I recognized both the portrait and the name. The beautiful woman in the portrait with sleek blonde hair and gray blue eyes was Lorraine Marlow, and she had been dead long before the Serendipity went down in the Gulf. I’d often admired this regal portrait on the landing of the central staircase in the college library. I felt a prickle of unease. The man with the flashlight addressed the portrait in a familiar way. I was sure this was not the first time he’d spoken to her.

“—and I’ll keep looking every night ’til I find out who’s behind the trouble. I shouldn’t have shot my mouth off to that reporter. I wish I’d never talked to him. I thought Joe Cooper was a good man, been to Afghanistan and come home to go to school and make something of himself. But he’s disappointed me.”

My eyes had adjusted to the dark. The speaker was bear-shaped in a dark cotton jacket, dark trousers, and work boots. The left sleeve of the jacket was pinned to the shoulder. I wondered how he had lost that arm. He moved uncomfortably from one foot to another. “Miz Lorraine, I’m doing my best to get to the bottom of it, but there’s so many ways in and out of the library. If only I hadn’t talked about you. I can’t believe what he wrote. I’m going to tell him what I think about him.”

“Everything will work out. Joe’s a nice young man.” The voice was high and clear with a bell-like tone, a kind voice, yet definitely that of a woman accustomed to deference.

I looked wildly about. But there was only the man with the flashlight looking up at the portrait.

“Miz Lorraine, did you see what he wrote? About the rose in his office?”

“I did leave that particular rose.” The light musical voice sounded happy. “I’m glad. I was there when he talked to that young woman. They are meant for each other. But like so many of the young, they think careers are more important. But I had nothing to do with the other roses.”

I looked up at the portrait, managed a silent swallow. I had no doubt the woman’s voice belonged to Lorraine Marlow, who had been dead for many years.

“He didn’t deserve a rose.” The deeper voice was resentful, angry. “Not when he’s acted the way he has, writing you up in the same way he wrote up the gargoyle and that book.”

“Dear Ben.” There was laughter and affection in her voice. “Everyone deserves a rose. Love is all that matters. Anyway, none of this is your fault.”

I scarcely breathed as I listened. The beautiful high voice, full of light and grace and kindness, was encouraging. Nonetheless, I was listening to a disembodied voice with no visible speaker and I knew without doubt I was at the right place at the right time. I had found Wiggins’s damsel in distress.

In my excitement, I blurted out, “You must be she!”

Wiggins was upset because she was in trouble. He’d let slip that he’d always paid particular attention to Adelaide. Because of Lorraine Marlow? How could he have known her?

I reached out, touched the edge of the portrait frame. “Lorraine, can you tell me—”

“Who’s there?” His flashlight beam flipped up the stairs, down, over the railing to the dark rotunda below. “Nobody there. Must be upstairs.” He clattered up the steps, shouting, “Stop! Whoever you are. Trespassing. Stop.” Obviously Ben hadn’t confused my lower husky voice with Lorraine’s, and he was in full pursuit of an unseen interloper.

Now the portrait was in darkness, but I remembered Lorraine Marlow’s long, delicate face framed by soft golden hair, her smooth forehead, aristocratic nose, high cheekbones, and delicately pointed chin. There was an elfin quality to her beauty, a haunting sense of gentleness and kindness lost too soon. Her widowed husband endowed the library with much of his fortune after her early death, and the portrait was hung in her memory. At his death, Rose Bower, their fabulous estate that adjoined the far side of the campus, was left to Goddard College and became the site of the college’s most elegant parties and receptions and served as well as guest quarters for distinguished visitors.

Thoughts tumbled in my mind. Wiggins’s summons. His distress. Precept Two. My bewilderment when my promise to strictly adhere to Precept Two—“No consorting with other departed spirits”—made Wiggins even more miserable. Dastardly deeds in Adelaide. Well, why didn’t he just tell me I was supposed to help Lorraine Marlow and to heck with Precept Two?

Ben was too far away to hear me, but I kept my voice low. “Wiggins sent me.”

Silence.

Words are not always necessary. Emotions communicate without a whisper of sound. I knew Lorraine Marlow listened, breath held, amazed, surprised, shocked. Wiggins meant something to her. Yet I felt resistance. It was as if a door had closed solidly, firmly.

I plowed ahead. It always amazes me how often everything could be made right if people spoke honestly. However, no one has ever accused me of pussyfooting around. “I’m Bailey Ruth Raeburn. I grew up in Adelaide.” I was trying to remember some of her history. I thought she had come to Adelaide after she married Charles Marlow.

No response. The only sounds were slamming doors on the second floor and Ben’s gruff shouts. The silence on the landing was sentient, wary.

Was there sadness in her silence? Or dismay? Or fear?

I said gently, “How did you know Wiggins?”

A quick intake of breath.

Train travel dominated the country in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Women in long skirts alighted from carriages to enter bustling stations, accompanied by hatted men in dark suits. Wiggins was a product of his times in a stiff white shirt, suspenders, black woolen trousers, and high-topped black shoes. I knew him in his Heavenly station. I didn’t know anything about his life on earth except that he had loved being a stationmaster. “Wiggins has a train station in Heaven. He sends emissaries to earth on the Rescue Express to help people in trouble.”

“Ooh.” Her voice was soft. “How like Paul. He loved his station. He planned to go back—” She broke off.

Paul? Go back? Lorraine and I both were making discoveries. Wiggins’s first name was Paul. She hadn’t known him as a stationmaster. “When did you know”—I paused. I scarcely felt it proper to call Wiggins by his first name—“him?”

“Paul sent you here?” There was a wondering tone in the light, high voice.

“I just arrived.” I put two and two together. “Wiggins wants you to come to Heaven.”

Abruptly, the silence was empty. I was alone on the landing. The portrait was only a picture.

Heavy steps announced the watchman’s return. He was a little breathless from his exertions. He lifted the flashlight, and the lovely portrait was again revealed. “I didn’t find anyone. I don’t know about that voice. Maybe it was the wind and I got it mixed up in my mind. Sorry if I worried you, Miz Lorraine. I guess everything’s okay tonight. But something happened three nights in a row. Why not tonight? Maybe”—hope lifted his voice—“I got ’em too scared to come back.” A pause. “Whoever’s coming knows all about the library and when I make my rounds and, like I said, I can’t be everywhere at once. I’m going to mix things up the next few days, spring some surprises. Now”—he tucked the flashlight under his arm, touched his cap with two fingers in a respectful salute—“you rest easy. I’ll see to everything.”

He turned and stumped down the steps, flashlight beam flicking from side to side.

<We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...